The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Self-inflicted catastrophe

In the last few days, while MMT has been debating with Paul Krugman, several key data releases have come out which confirm that the underlying assumptions that have been driving the imposition of fiscal austerity do not hold. Ireland led the way in early 2009 cheered on by the majority of my profession who tried to sell the world the idea of the “fiscal contraction expansion”. Apparently, there were millions of private sector spenders (firms and consumers) out there poised to resurrect their spending patterns once the government started to reduce its discretionary net spending. Apparently, these spenders were on strike – and saving like mad – because they feared the public deficits would have to be paid back via higher future taxes and so the savings were to ensure they could pay these higher taxes. It is the stuff that would make a sensible child laugh at and think you were kidding them. Now, the disease has spread and the data is telling us what we already knew. The economists lied to everyone. None of them will be losing their jobs but millions of other will. And the worse part is that the political support seems to be coming from those who will be damaged the most. Talk about working class tories! This is a self-inflicted catastrophe.

On August 16, 2011, Eurostat released the Flash Estimates for second quarter 2011 GDP which presented a very bleak picture indeed.

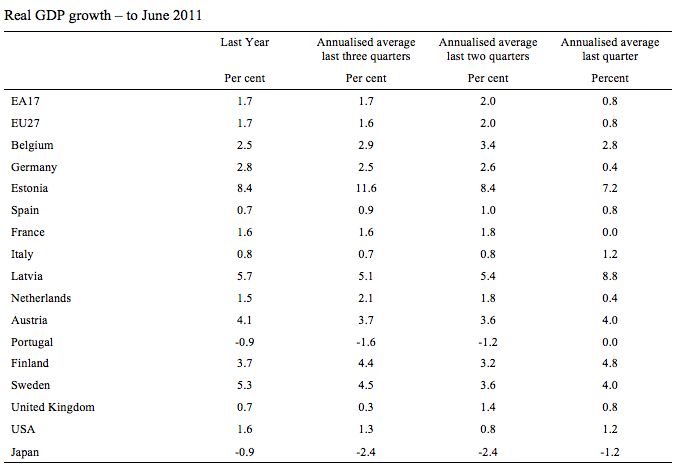

I assembled the following Table to summarise the trends over the last year. Some nations were not reported (as the flash estimates are not available – for example, Ireland, Greece etc).

The first data column shows the actual flash estimate for real GDP growth in the 12 months to June quarter 2011. The next column is the annualised equivalent of the average growth over the last three quarters, then the annualised equivalent of the average growth over the last two quarters and finally, the annualised equivalent of the growth in the June 2011 quarter. This sort of data can help you understand the movement in the economies in question.

If we compare where the economies were at the beginning of the year in terms of real GDP growth and where they are now, most nations are slowing. The few exceptions are Italy, Latvia, Austria, Finland, Sweden, and the US. But Austria, Sweden and the US are in decline compared to where they were a year ago.

Japan can be excluded for now because of the impact of the Tsunami.

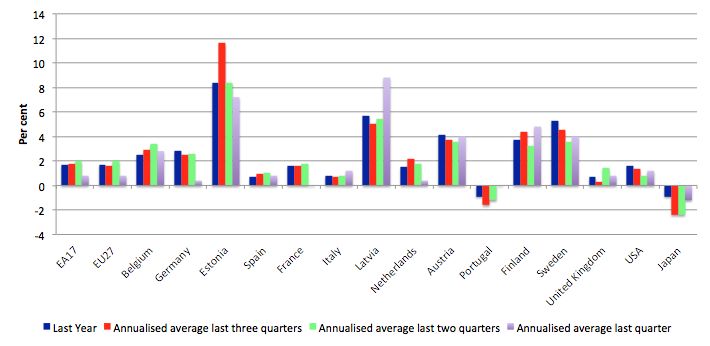

It is hard data to graph effectively, but for those who prefer pictures the following graph just reproduces the data in the Table.

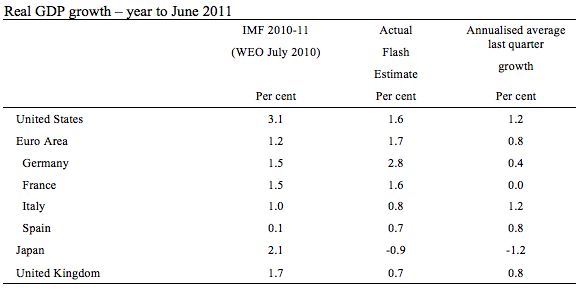

The next Table summarises the IMF World Economic Outlook estimates for selected countries as at their July 2010 update. I averaged their 2010 and 2011 forecasts. The other columns are derived from the previous Table.

Their estimates for the US, the UK (and Japan – but they cannot be held responsible here) are very poor. While their estimates for the actual European data for the year to June 2011 were reasonable it is clear that the earlier growth in 2010-11 which was driven by the prior fiscal stimulus packages has come to an end.

The IMF has been constantly calling for “fiscal consolidation” and now governments are imposing fiscal austerity regimes onto their economies the results are clear – there is a major slowing of growth and if we assessed the annualised June 2011 equivalent against the IMF forecast for 2010-11 the IMF estimates were very poor even for Europe.

The early signs of growth are gone.

The IMF also seems to be flip-flopping a bit at present as their forecasts fall apart.

They were leading the charge in advocating fiscal consolidation (read cuts) as the early signs of growth appeared courtesy of the fiscal stimulus packages.

As David Blanchflower points out in his recent New Statement article (August 16, 2011) – Christine Lagarde’s attack on Osbornomics is damning – the British government used statements made by the IMF as being supportive of its fiscal austerity drive.

Blanchflower points out that even as late as June 6, 2011 “George Osborne said he had been “vindicated” in a debate over spending cuts after the International Monetary Fund backed his austerity measures.”

But the latest offering from the new boss of the IMF – fresh from having blood on her hands as the French finance minister wrote an extraordinary piece in the Financial Times (August 15, 2011) could not be construed as being supportive of the British government’s demolition of its economy nor for that matter the conduct of the American polity.

Here is the IMF page access – Don’t let fiscal brakes stall global recovery. Lagarde is now saying categorically that:

After the crisis unfolded in late 2008, global policymakers came together to act with common purpose. Their efforts saved us from a second Great Depression, by supporting growth, attacking sclerosis of the financial arteries, rejecting protectionism and providing resources to the International Monetary Fund. It is time to rekindle that, not only to avoid the risk of a double-dip recession, but also to put the world on the path of solid, sustained and balanced growth.

That is fiscal policy was effective! Just ask the IMF.

She now claims that crisis has moved from the “poor health of financial institutions” to the “doubts about the health of sovereigns and the tricky feedback loop to banks”.

What follows tells me that this article is another ad hoc attempt by the IMF to distance itself from the damage that its prescriptive aggression has caused.

I say that because while she is now expressing worry about the falling growth rates and attempting to claim leadership in a more reasoned approach (hence the claim by Blanchflower that she is basically attacking the Osborne-approach), the underlying narrative and understandings are still the same old – public debt is bad and introduces a solvency problem.

She says that the policy interventions that saved the world have:

… left behind a legacy of public debt – about 30 percentage points of gross domestic product higher than before, on average, in advanced countries.

So there are no easy answers.

Yes, if she could get beyond her ideological blindness she would realise that non-government wealth rose by those 30 percentage points of GDP courtesy of the fiscal interventions and provided the private sector with some room to save and reduce their very risky debt exposures.

Public debt is just private wealth. Public debt interest payments are private income. Both good (excluding considerations of equity – that is, who is benefitting).

It is true that the public debt (and deficits) in the EMU are problematic given the ridiculous nature of the monetary system. But Lagarde is as implicated in that as anyone. They introduced a system that could never withstand a serious negative aggregate demand shock and are now reaping the costs of that poor design – which was imposed on member nations by neo-liberal zealots on large, secure salaries.

The problems in the EMU should not cause major macroeconomic issues in the rest of the advanced world though. Nations like the UK, the US, Japan etc are not dependent on bond markets for their welfare. But in thinking they are, their respective governments are plunging their economies and the rest of us into the same recession-mired bog that is clearly the European experience.

Lagarde also repeated the mantra that “(f)or the advanced economies, there is an unmistakable need to restore fiscal sustainability through credible consolidation plans”. Given that the national governments do not control the budget outcome and given they cannot accurately forecast their external and private domestic sector spending decisions very well it is nonsensical to expect governments to announce budget trajectories

The best fiscal “consolidation” plan is to stimulate growth with on-going and larger (if needed) fiscal support. Then let the automatic stabilisers take care of the cyclical component of the budget outcome as economies move closer to full capacity utilisation and then make assessments about the public/private balance in the output mix.

Following that strategy – which means ignoring public debt ratios and all the other irrelevant financial ratios – will improve the things that matter – real things – output, employment, incomes, welfare.

Largarde knows though that cutting public spending is damaging. So now she claims that:

… we know that slamming on the brakes too quickly will hurt the recovery and worsen job prospects. So fiscal adjustment must resolve the conundrum of being neither too fast nor too slow. Shaping a Goldilocks fiscal consolidation is all about timing. What is needed is a dual focus on medium-term consolidation and short-term support for growth and jobs. That may sound contradictory, but the two are mutually reinforcing. Decisions on future consolidation, tackling the issues that will bring sustained fiscal improvement, create space in the near term for policies that support growth and jobs.

It is contradictory. If private businesses think that there will be a sharp fiscal contraction in some defined future period that will impact on their investment decisions. Households will also be negatively impacted.

The government should always focus on the real economy and educate the citizens to disregard the “budget outcome”. As a stand-alone number the budget outcome each period has no meaning at all.

But the real GDP growth data, and employment growth and unemployment rates carry intrinsic meaning about our lives and our well-being. That is the only role for government.

So while the IMF is now implicitly arguing for fiscal expansion – a total rejection of the UK fiscal strategy and the mad republicans in the US to name a few – it still doesn’t understand that governments rule not bond markets.

By tying in the EMU with other advanced nations they are also falling into the “conflation of non-comparable monetary systems” error – a fatal mistake that reveals among other things a deep-seated ignorance and should disqualify the speaker from further input into the policy debate.

British unemployment rises

The UK Office of National Statistics released their August 2011 – Labour Market Statistics yesterday (August 17, 2011).

The data showed that:

- Unemployment jumped sharply and long-term unemployment rose – “The total number of unemployed people increased by 38,000 over the quarter to reach 2.49 million. The number of people unemployed for up to six months increased by 66,000 over the quarter to reach 1.23 million. This is the largest quarterly increase in this series since the three months to June 2009. “

- Underemployment rose to record levels – “The number of employees and self-employed people working part- time because they could not find a full-time job increased by 83,000 on the quarter to reach 1.26 million, the highest figure since comparable records began in 1992.”

- The unemployment rate rose – “to 7.9 per cent of the economically active population, up 0.1 on the quarter”

- Unemployment benefit claimants rose by 37,100 on June.

- Redundancies rose – “mainly among women”.

- Number of women out of work highest since 1988.

- Youth unemployment rises to nearly 1 million.

- Unfilled vacancies (a component of labour demand) plummeted – “The total number of vacancies is the lowest since the three months to November 2009.”

- There was no change in the employment rate. Employment failed to grow as fast as the labour force

The UK Guardian article (August 17, 2011) – UK unemployment jumps as economy falters – said

Britain’s lacklustre economic recovery is taking its toll on the labour market, with unemployment increasing by 38,000 over the three months to June – the largest jump since spring 2009, when the UK was in recession …

With GDP growth sliding to just 0.2% in the second quarter of the year, analysts had been warning for some time that weaker growth and fragile confidence could deter firms from hiring new workers and lead to a renewed rise in unemployment.

So expect the labour market data to deteriorate further in the coming months.

And if you were uncertain about what drives business investment and confidence then this comment from the chief economist at Markit (the industrial activity survey firm) will set you straight:

Business confidence clearly needs to rise before employment growth will pick up again, but at the moment the surveys suggest that companies remain worried about economic growth both at home and abroad and are generally erring towards cost-cutting rather than expansion.

No mention there of all those private sector spenders who have been waiting for the national government to hack into public spending before they spend.

It is a clear causality that is playing out – spending equals income – income drives output – output drive employment.

The national government now has been in power for more than 12 months and the data is getting worse each month. The latest labour market figures are in the terrible category.

Their fiscal strategy has already failed.

As Larry Elliot noted in the Guardian (August 16, 2011) – UK unemployment jumps as economy falters – the government

… inherited an economy that was growing quite strongly but activity came to an abrupt halt last autumn and has flatlined ever since … The recovery in manufacturing has petered out, denting hopes of a rebalancing of growth towards production and exports.

Other predictions that haven’t panned out

And then you read this sort of repetitive nonsense published in Murdoch’s News Limited – The Australian (August 18, 2011) – Stop Cairnsian spending and keep surplus promise.

This character is a professor of economics at an Australian university (Griffith, QLD). I advise no students to take a course with him. He is a former Commonwealth Treasury official.

I have written about this person’s analysis before – Lost in a macroeconomics textbook again. That was in 2009 when he was in the running for the “billy blog worst Op-Ed column of 2009 award”. He regularly contributes to The Australian and the message is always the same. He hates government spending and deficits even more so and thinks the recession is all down to too much wasteful fiscal stimulus.

In the the Op Ed I previously commented on he mindlessly applied the model presented in most intermediate mainstream macroeconomics textbook and made various predictions like Australia’s credit-rating would be downgraded and foreign investors would “take fright” and we would see spiralling interest rates. Nearly two years have passed and the nation is still intact.

He has repeated that theme often in the last two years.

So today he was at it again but in the theme of this blog – predictions that failed – I thought his Op Ed was demonstrative.

Makin writes:

ALMOST a year ago on this page … I predicted the economy would suffer for some time afterwards from the effects of the increased government spending and borrowing between 2008 and 2010 in response to the North Atlantic banking crisis, a legacy that would manifest through higher interest rates, less investment, lower economic growth than anticipated and increased inflationary pressures.

By and large, these predictions have eventuated, though interest rate levels are admittedly lower than expected.

The rest of his article attempts to justify why the federal government should be in surplus, despite a current account deficit and a very cautious private sector – the household component carrying record levels of debt and clearly desiring to save to reduce the risk of that debt.

But the significant thing is that he does reflect at all on why interest rates “are admittedly lower than expected”. His beloved macroeconomics textbook model would have predicted that rising deficits would cause interest rates to rise via loanable funds pressures (public debt absorbing all available saving) and this would stifle private investment and growth.

However private investment has been relatively strong and concentrated in the mining sector where there is demand for output.

The crucial point is that the lynchpin of his theoretical approach which ties the links together is that interest rates and bond yields should have gone through the roof and domestically-sourced demand-pull inflation should be accelerating.

Neither of those events have occurred. The slight rise in inflation has largely been due to natural disasters – floods and cyclones – that have compromised food supply and energy prices reflecting decisions made by the OPEC cartel and unrelated to domestic events.

Even then inflation is not an issue in Australia at present.

Further interest rates have not risen for nearly a year and bond yields remain very low.

So wouldn’t that suggest to anyone that a model that predicted these things could not possibly be a correct representation of how the modern monetary economy works operates?

Conclusion

The world economy is slowing again and there is only one reason for it – policy makers are being seduced by an economics approach that fails to accord with the way the economic system works.

It fails basic tests – like an appreciation that spending creates income. We cannot expect real output to rise when a major component of the marginal growth in aggregate demand is reduced (public spending).

We cannot expect private investment to be strong when consumers are unwilling to return to pre-crisis (credit-driven) consumption levels.

We cannot expect consumers who are saddled with massive debts and/or are enduring entrenched unemployment to bounce back and drive economic growth.

We cannot expect all nations to suddenly experience an export boom which overwhelms the import side of the current account and adds more to aggregate demand than is lost from fiscal austerity.

For all those reasons, budget deficits should be larger at present and governments should be demonstrating up their commitment to full employment and renewed economic growth. The best place to start is to introduce a Job Guarantee – large-scale employment creation programs.

Such a scheme – putting solid income into the hands of the poor and unemployed – would stimulate aggregate demand in essential sectors – food, retail, housing, schooling, health etc and within two quarters the recession would be over and investors would start getting bright-eyed again.

British role models

Much is being made of the criminal youth in Britain and their personal responsibility in perpetuating the destructive riots last week. I suppose they were influenced by their role models.

1. Politicians on both sides of Parliament in the UK who rorted their expense allowances – the so-called United Kingdom parliamentary expenses scandal – provided an excellent demonstration to anyone wanting to get material wealth illegally.

2. The Fourth Estate – so far the Murdoch Empire. The established media institutions demonstrated how the only goal worth considering was private gain and matters of integrity, morality, the law were secondary to the main game – private profit.

3. The exemplars from the financial sector – remember the character who taunted the doctors and nurses in London who were demonstrating – waving a ten pound note and telling them to get a job. I know that individual was sacked by an embarrassed Deutsche Bank who apparently told all staff to lie low given how furious the public were over their bonuses. The head of the London-based Deutsche Bank was paid “more than £10million last year” (Source). How many of the bankers who in the pursuit of personal greed lied and cheated people into investing in bad assets which led to the crisis have been called to account? How many have been given custodial sentences, not to mention sentences that are much harsher than precedent would suggest (see article – Britain’s Harsh Riot Crackdown.

Their slogan – you’ve got it, we want it – anyway we can.

4. Ratings agencies – who admitted to the US Congress inquiry that they had faked AAA ratings in return for private profit – and whose ratings duped investors into buying toxic assets which led to the crash. How many of them are serving custodial sentences and being forced to pay back the millions who have lost their jobs, their income and their wealth? Their slogan – do anything for a buck.

Role models all of them.

Groundbreaking news

This was a groundbreaking news report this week – S & P Downgrades Iowa’s IQ.

Apparently the “Straw Poll” alarmed the ratings agency.

Hysterical (thanks Jim).

That is enough for today!

The rioters forgot to learn one lesson from the bankers and rating agencies. First you buy the politicians and get them to change the law and regulations so that your nefarious activities are legal. Then you do the looting.

I had a deeper look at the inflation figures yesterday. Some of the component categories are quite illuminating.

There have been substantial rises in

– Value Added Tax

– Tax on Spirits and Beers

– Housing rent – particularly the rent on social housing.

– Rail fares due to withdrawal of subsidies

– Education – particularly tuition fees due to withdrawal of subsidies

Spot the connection there?

The others are

– Transport and health insurance

– Mortgage fees

ie the financial sector.

So with the government and the financial sector against us what chance has the UK got?

I find myself generally in agreement with MMT and its prescriptions. I would even suggest these prescriptions are approximately equal to “soft Keynesian” economics which would also (I think) accept net budget deficits over the full cycle(s).

My point of view is this. The MMT proposition “national government that issues its own currency can never become bankrupt in terms of liabilities accumulated in that currency” though containing a core of truth is perhaps tendentious being an over-abstracted and simplified theoretical point . We need to ask what happens in practice (and in a world of floating currencies) when a government follows this path to an extreme. Clearly, the extreme leads to hyperinflation. I suspect the extreme will also lead to the functional equivalent of bankruptcy (for a small country anyway) if not technical bankruptcy according to that nation’s own accounting. Other nations and businesses would not accept their currency.

On the other hand, MMT shows us that insisting on balanced budgets for their own sake (year on year or over the cycle) based on a crowding out theory is an absurdity and in some ways the reverse of the truth. It is also a clear case of the financial tail wagging the real economy dog. Balanced budgets are a kind of accounting fiction. Fiction in the sense that they are claimed to be necessary (in and of themselves) to the real economy when they are not. It is a form of letting an arbitrary accounting norm determine and distort outcomes in the real economy. What is necessary in the real economy (under social democratic and humane principles) is full employment first and inflation in an acceptable band which will likely be a bit higher than the current band acceptable to the Reserve Bank in Australia.

The more I learn about this, the more scared I get. Had I at first some kind of confidence in the ability of our politicians to do reasonable well, that confidence has now turned into outright fear. It feels like I’m sitting in the back of a car racing at high speed and there are a couple of monkeys behind the steering wheel. The people in power, both in the US and EU and elsewhere, both politicians and economists, have no clue at all about how things work. They are literally like the monkeys frantically turning the wheel and pushing the pedals.

I just hope that someday soon I’ll come across some new blogs and read about how all this MMT stuff was just some crazy theory, not how things work at all, so I can go back to the warm cozy feeling knowing our leaders will take the measures necessary to get things working again in our economies…

Perhaps nobody has read this yet, but here’s a piece co-authored by the H.M.’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr. Osborne; and by some colonials, among them one Wayne Swan, from Australia.

“Global recovery requires political courage”, Financial Times, 14-08-2011.

By Jim Flaherty, Pravin Gordhan, George Osborne, Tharman Shanmugaratnam and Wayne Swan.

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/c5664720-c664-11e0-bb50-00144feabdc0.html

Somehow I suspect we in Oz might not be off the hook.

Hi Bill,

as always, very pleasant reading, do you have a back up if you get run over by a bus? A piece of research i’m reading at the moment “The Debt-Inflation Cycle and the Global Financial Crisis”. Thought you’d like it. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1729228

regards,

Dee

Ikonoclast said:

“My point of view is this. The MMT proposition “national government that issues its own currency can never

become bankrupt in terms of liabilities accumulated in that currency” though containing a core of truth is

perhaps tendentious being an over-abstracted and simplified theoretical point .”

There’s nothing abstract or over-simplified about this statement as far as I can see. A sovereign government *can’t* become insolvent with respect to debts denominated in its own currency. That is a statement of fact, it does not merely contain “a core of truth”. Whether or not a government can cause inflation by over-spending is a separate issue, and one which is amply addressed on this blog and others, but I don’t see how it’s helpful to redefine “become insolvent” to mean “cause hyper-inflation”. I agree that the statement on its own might not not be enough to convince someone that, eg, budget deficits are not per se a bad thing, but then MMT has many more strings to its bow than simply “sovereign governments can’t run out of the currency they issue”.

“We need to ask what happens in practice (and in a world of floating currencies) when a government follows this path to an extreme. Clearly, the extreme leads to hyperinflation. ”

It’s clear that Ikonoclast hasn’t read all of the MMT materials available here. There’s a clear acknowledgement that attempts at pushing an economy beyond full can be inflationary. That’s why the goal is ‘only’ to strive for full employment!

Interestingly, Krugman’s explanation of why the “bond vigilantes” are only going after countries like Greece instead of the USA and Great Britain here: http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/08/17/the-printing-press-mystery/

Seems to me like it’s straight out of MMT. Maybe he’s coming around.

Maybe I am just attacking a straw man. However, it does seem to me that strict insistence in all cases on the proposition “national government that issues its own currency can never become bankrupt in terms of liabilities accumulated in that currency” is merely a formal truism of the sort illustrated by the equation 1 = 1. No one has answered the point I made above about functional bankruptcy (for want of a better term) as opposed to formal bankruptcy. I did add the caveat that this functional bankruptcy might only apply to small countries.

Latvia and Estonia are faring quite well then. An example of how austerity measures can also work?

Iconoclast: of course you are right. MMT is full of formal word games such as this bankrupcy thing. The simple truth is that once government spends too much using the printing press (for where the threshold is see this article http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2011/04/functional-finance-vs-the-long-run-government-budget-constraint.html) people simply lose trust in currency and will stop using it. They will not buy government bonds, they will not save their money on interest bearing accounts until government promises to balance its long term budget.

I do not know why this simple truth evades the MMTers as this is how “real world operates”.

J.V.,

Your link appears to be broken….. DARN! 😉

PS The govt doesn’t have to print money any more, they have computers to keep track of balances these days…

Resp,

I’m slowly getting it that MMT is not diametrically opposed to the mainstream economic paradigm. Rather it corrects a few (important) core misconceptions and debunks some commonly held erroneous theories.

The Capitalist system is racing down a path hell bent on creating a highly polarized society. From historical precedent this will eventually lead to the destruction of that evolved society at no trivial cost in lives and misery.

MMT proponents offer guidelines and suggestions to mitigate this social polarization. This could arrest the neo-liberal onslaught and extend the longevity of the system. The fundamental flaws are still within the capitalist system.

In my short lifetime I have seen:

1) Crushing of unions in the UK by Margret Thatcher, crippling the wage negotiating power of the workforce.

2) Globalisation, outsourcing and the mobility of labour nailing the last stake in the heart of the workforce, we are now in an endless race to the bottom for wages and conditions.

3) Relentless stream of privatization, moving wealth from the public domain to the private sector and under direct control of the financiers.

4) Growth of trans national corporate monopolies like Microsoft beyond the reach and control of National monopoly legislation.

5) Loading of unconsionable debt onto the peons. Housing debt, auto loans, study loans, credit cards etc etc. A lifetime of passive debt servitude.

6) Financialisation and the increasing control of welfare and public services by financiers. Private health, private education, unemployment insurance, private pensions, life insurance, this insurance, that insurance, pet insurance, funeral insurance.

It’s all headed in one direction. An exceedingly wealthy minority. Relentless erosion of living standards and debt servitude for the rest of us.

MMT doesn’t solve these problems, but it does give us a better vehicle with which to fight back. Keep it up Bill.

Rant over.

There’s more regressive taxation too…that’s a biggie they impose on us as they slap our faces and laugh.

J.V. Dubois:

“I do not know why this simple truth evades the MMTers as this is how “real world operates”.”

It does not. Never, not once, has Bill ever advocated printing “infinite money” or “infinite deficits”. Neither has he denied the existence of inflation as a danger when spending TOO much. What, then, is the difference between his idea of too much versus the mainstream idea of too much?

Mainstream economics suggests ANY deficit is too much. Bill’s alternative is that too much is when full employment is reached.

Please have a read of this series of blogs:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=2905

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=2916

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=2943

Despite my questioning of some of the formal aspects of MMT (“formal” in the sense of mathematical or philosophical formalism), I don’t want Professor Mitchell or contributors to get the idea I am anti-MMT. I am in full sympathy with the socio-economic goals of MMT, at least in the form put forward by Professor Mitchell. I am in qualified agreement with parts of MMT’s fiscal and monetary analysis but I do also some reservations and queries about it. In raising these reservations and queries, I certainly don’t want to be identified as supporting neoclassical economics or neoconservatism. That would be anathema to me.

I have raised the issue of objections on the grounds of formalism, namely;

(a) that MMT is in some respects just a formal system, internally consistent because it is constructed to be that way; and

(b) that these internal consistencies are obtained by abstracting simple elements from a “still-frame” of the system as it were; and

(c) that this system has in reality evolved complexity over time and keeps revolving complex-ly as it consists of many continuous feedback loops rather than simple sets of “a” to “b” causality. (In other words, I am talking about circular causality of the type exemplified by “a” affects or effects “b” which affects or effects “c” which affects or effects “a”.)

I am not all clear that I am right in my objections so bear with me and even refute me if possible. It is simply troubling me to think that MMT might to some extent simply be a formal structure as critiqued above.

Perhaps I can make my objections clearer by giving an example. The example involves government spending and government taxation. MMT (if I understand it correctly) says that governments spend by fiat by creating money ex nihilo and that income in the form of taxes is not a necessary precursor to spending. I agree with this point in the pure form. I agree that government finances are not like household finances and I agree with the way that MMT exposes the absurdity of clinging to the fetish for balanced budgets or surpluses even in times of contraction and/or high unemployment.

However, to make the point that (correct me if I have MMT theory wrong) money is created by government spending and destroyed by taxation is more a semantic or formal argument than a real point when the two are regarded as pehneomena occuring in tandem, in real time as part of a compex revolving and evolving system. The two ways of looking at it are functionally equivalent at the formal level. Take the example of a government budget being perfectly balanced in a given year. I can say $X billions are created by fiat spending and $X billion are annihilated by taxation to gove a budget balance of zero. Or I can say $X billions are spent, creating a debt in the national account and then this debt balance annhiliated, annuled or paid out (it’s all semantics) by the taxation “revenue”. All of I have done is move where I do my subtraction on the balance sheet. It is a formalism either way.

To say that taxation is not necessary for spending (does MMT say this or am I setting up a straw man?) is formally correct in isolation but I would argue not empirically correct, at least not in a standard modern economy. Taxation is not necessary for any discrete piece of government spending. Any discrete piece could be deficit funded. But government spending in total as an ongoing annual phenomenon is predicated on taxation as a phenomenon precisely because taxation generates a liability to the government which can only be paid in the fiat currency AND precisely because taxation offsets government spending more or less thus keeping money supply and inflation in check.

I am sorry if my objections are not clear. It’s just that MMT interests me a great deal but also bothers me in the sense that I have something nagging me at the back of my thinking which intimates that there is an aspect of logical fallacy about it or at least some components of it. I could write more but will leave it at this for the moment.

It has occurred to me, since writing the above, that MMT is a formal system because it describes a formal system. If this is true then it fully rehabilitates MMT. The formal system it describes is our currently evolved financial economy (public and private sectors combined).

Any comments on my two posts?

Dear All

The tone of conversation is getting a little bit personal. Please stay above that level.

For those who mistakenly think the monetary operations that accompany deficit spending add to the inflation risk – you need to (a) study how the central banking and banking system works; and (b) read more of my work and the works of other MMT proponents. Stay clear of monetarist blogs that just reiterate mainstream textbooks.

For all others who understand these things correctly – stay calm.

best wishes

bill

Ikonoclast:

“Taxation is not necessary for any discrete piece of government spending. Any discrete piece could be deficit funded. But government spending in total as an ongoing annual phenomenon is predicated on taxation as a phenomenon precisely because taxation generates a liability to the government which can only be paid in the fiat currency AND precisely because taxation offsets government spending more or less thus keeping money supply and inflation in check.”

Absolutely spot on. Taxes don’t fund spending; they give value to the currency, which is what allows the spending. The closest analogy I can think of is how you don’t need gravity to breathe, but gravity creates the atmospheric pressure that allows you to do so.

It’s a common mistake to think MMT means no more taxes, when in fact it gives us a deeper understanding of why they are so important.

If the broader populace knew the extent of the massive tax swindle being perpetrated on a daily basis maybe we would see more widespread unrest. Government, big business, investment bakers, tax lawyers et al – all have helped devise tax systems which ae incredibly biased toward those with money. They argue their tax avoidance activities are within the law and they are probably right. But the law was written with their best interests at heart. And what a huge waste of resources with so many people getting paid big bucks to get reduce taxes for big business and rich people.

I think I am calm. I have raised some philosophical questions about the formalism of MMT. I would be intrigued what knowledgable advocates of MMT think about those issues. They might think my quibbles are nonsense. I’m quite happy to have that explained simply and clearly if it is so.

Also, I do not (yet) agree that the equation (G-T) = (S-I) – NX is correct. Maybe I just haven’t read far enough in Deficit Spending 101. Why has no mention been made of money creation by private bank lending?

Don’t think it’s you Ikonclast…… might be me.

The money creation by private banks is the horizontal/ vertical thing (I think). When a bank makes a loan they do kind of magic money out of thin air, but they always create two accounts. One is a credit and the other a debit, the two accounts always net to zero so the money creation is only for the duration of the loan.

When Governments credit someone’s account they don’t debit another account so that is considered a more permanent type of money creation. If they issue more credits than they take back in taxation they issue bonds to cover the difference. In this way we are supposed to think the extra money is only temporary. We are told the Government is borrowing to fund spending. The bonds will gracefully expire, paid off with taxes when we run a surplus budget one fine day.

It’s all a bit silly really because they just pay back expired bonds with freshly minted cash and promptly issue new bonds if there is any deficit. It’s all a big fat jolly jape for the Banks. There’s never an end to it and they make a fortune. It’s not entirely frivolous because it is part of the process to maintain stability of the currency. Bill reckons there are other simpler ways of achieving the same objective.

Please get a proper academic run down of the situation using the proper words and all that. I suspect I have the gist of it correctly though.

Ikonoclast:

Don’t worry, I think he was only telling his supporters to calm down.

Private bank lending creates money but also creates a 1:1 corresponding liability inside the system. Every deposit is some bank’s liability & reserve (they have to eventually pay it back if you withdraw) and every loan is some bank’s asset. Reserves created by loans are fully cancelled out by the loans themselves.

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=6624

Iconoclast: I think that Bill may be thinking about me to get calm. I will try, but then it would also serve MMTers to tone down a bit too in their blogs about how it is that nobody understands them.

As for your philosophical objection I totally and wholeheartedly agree with you. MMT is formal and internally consistent system because it is design to be so. Take this example

I-S+G-T+X-M=0

where I=investment, S=savings, G=government spending, T=taxes, X=exports, M=imports.

Rearrange, assume a closed economy, and S-I=G-T. And now you have “Private Savings = Government Deficit”. But this is only accounting identity! An it is not any news, it was known for decades. If you divide economy into any two sectors, like men and women you may says such things like “women savings = men deficit”. So what? Nick Rowe hits the nail by this claim

“You [MMTers] think you have discovered something that nobody else knows. So you come across as a cult, saying “the number of children = the number of sons + the number of daughters, and this equation is what determines the number of children people have, and all those stupid demographers don’t get it!”

Andrew: “It’s all a bit silly really because they just pay back expired bonds with freshly minted cash and promptly issue new bonds if there is any deficit.” You see, you are another victim of MMT word game. Government TECHNICALLY prints that money for prinicpal + interst, but with Long Term Budget Constraint (balanced budget promise) in mind it simultaneously destroys equivalent amount of money by taxation.

Or let’s assume balanced budget this year. If government prints (and uses to buy goods and services) exactly the same ammount of money as it gather in taxes, does it really make sense to “accuse” government from printing money? Does it really matter if paper notes collected are burned in Tax Office and new notes are printed, or if notes gathered as taxes are hauled by Trucks from Tax office for being reused by government? It is no of no consequence.

The same is valid for “deficit” financing – if government knows that in an hour a truck full of tax money is scheduled to reach incinerator are they not free to print the same amount of money NOW (because payment for some good or service needs to be done immediately)? It is again a word play. Government needs not wait for that money to actually burn prior to printing new ones. But from this observation to reach conclusion that government needs not to concern about how the tax money are to be scheduled for destruction (long term budget revenue) – and just print whatever money is needed for daily operations is wrong.

Me a victim? Bit harsh isn’t it. I think you are getting a bit fuddled with semantics and technicalities yourself there J.V.

Major point. There is virtually no difference between Government issuing bonds against the deficit or Government not issuing bonds against the deficit. Both are equally as inflationary. The recipients of the credit will spend in exactly the same manner regardless whether or not bonds were issued.

The bond issuance simply provides a zero risk safe habour for excess savings in the economy. If the Government does not issue bonds to match deficit, any derived incremental savings will still receive zero risk interest from the central bank at whatever interest rate the central bank deems appropriate to maintain stability of the currency. No difference.

Talk about tying your own shoelaces together. The victims of misrepresentation are those unemployed in the US, UK, Greece, Ireland etc etc who have been maliciously deceived into austerity measures by clowns telling them taxpayers fund deficits.

Every system that claims to be scientific is based on a formal system (algorithm). The algorithm is a set of tautologies that say nothing about the world. MMT is a macro theory so it begins with Y = C + I + G + (X-M), and transforms this using rules of formation and transformation into the sectoral balance equation, for instance.

The theoretical aspect of the science is the interpretation of the algorithm wrt causality. Macroeconomics needs a microfoundation that reveals the causal mechanisms in terms of individual and group behaviors. This connects the algorithm to reality and enables empirical verification, which is the criterion of truth of hypotheses in science. Explanations and prediction must not only exhibit correlation wrt date, but also be based on a theoretical causal mechanism that explains the why and how underlying observed correlation.

This is where it gets tricky. The big difference between MMT and other macro theories is the mechanism and direction of causation. For example, the ISLM model is base on loanable funds and changes in interest rates, which is basic to monetary policy. Supply side macro is based on investment and changes in taxes. Austrian economics is based on the real business cycle and changes in credit. Post Keynesianism is based on effective demand and changes in income and its distribution. MMT is a sub-school of Post Keynesianism that is based on offsetting changing propensity to consume/save from income with vertical (outside) money.

Different schools of thought attack each other on this basis. This debate reveals strengths and weaknesses in the respective theories. Through debate, often intense and partisan since economics has a normative component, agreement over “laws” is reached. These laws become the norms of the “normal” paradigm that dominates the scientific universe of discourse and doing “normal” science until enough anomalies arise to warrant a scientific revolution. This is basically the Kuhnian view. Hopefully, we are in the midst of such a revolution. When mainstream economists failed to predict and cannot explain a phenomenon like the global financial crisis, it is evident that something is amiss with the paradigm they are operating in terms of.

The normal paradigm in economics is largely the neoclassical (Walrasian) paradigm, with two different schools contending, the monetarist/neoliberal school following Milton Friedman, and the New Keynesian school, following Paul Samuelson, whose goal it was to combine Keynesianism with New Classicalism. Accepting general equilibrium, both schools base their theory on the theoretical concept of “natural rate.” Heterodox schools generally reject this, as did Keynes.

These theories as scientific explanations, as well as and their predictions that are often advanced as policy recommendations, are expressed as equations involving dependent and independent variables. Testing is done by applying data (factual) and hypotheses (counterfactual) to these equations using the relevant variables. Of course, empirical testing requires data, but this is not always possible in social and behavioral sciences, including economics, due to practical considerations.

Admittedly this is a picture painted with broad brush strokes, but I think it conveys the general idea of formalization in relation to scientific theory and how this relates to economics.

Andrew: First, government issuing bonds actually removes money from the system. It is sterilization operation – private sector gives you money, government gives them bond. Did you man bond sold by CB?

Second, fact is that price level is directly tied to monetary base – not to bonds. I heard here several times that money and bonds are interchangeable all the time (not only now when we are in liquidity trap). Is this what MMT thinks (I do not thik so) ? It is clear that high powered money have different impact on price level, as Scot Sumner showed in this blog http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=10116 Simply put, bonds and money are not equally inflationary. It is money which is inflationary.

Now if government (CB) pays interest on reserves, then money may not be inflationary. But then please be clear and state that you consider this way of operation.

Now if government just prints money which it spends and it wants to prevent inflation, it either has to:

1. Issue bonds

2. Pay interest on excess bank reserves created by money issuance

3. Increase taxes

Otherwise it creates inflation. Do you start seing the causality? Government prints money > spends it > no bonds or interest on reserves > increased taxes or inflation. So in short, government spending needs to be financed either by bonds, inflation, interest on reserves or taxes.

And last point. I know that if economy suffers from insufficient demand and if government spending “financed” by money printing EXACTLY fills this gap, thet it is a free lunch (no inflation). That is what I talk about here: https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=15753#comments My point is, that the same free lunch could be eaten by private sector instead (unless economy is in liquidity trap and private sector does not want this free lunch) in form of lower future taxes. So in a way we have sort of crowding out here (again not in liquidity trap)

J.V.

Reserves generated will *always* have the same interest rate as the target rate in an MMT system, or will be simulated with ‘repo’ and ‘reverse repo’ operations by the Central Bank. Most of the world is moving to interest on reserves. A lot of the MMT literature was created before the Fed and the BoE took that decision, which is why it discusses the ‘repo’ operations – and no doubt there are some central banks out there that still ‘repo’ as their primary tool.

‘repo’ being separate from the primary issue of Government bonds by the country’s Treasury.

So why are you persisting with a model that doesn’t include that fact? That model is wrong and does not represent the real world – which is the world MMT describes.

The MMT description has *never* suggested that any form of excess reserves left should attract an interest rate less than the current target rate.

The difference between bond issue and interest on reserves is that the former fixes the amount of government spending that will be transferred to the private sector for the tranche sold, whereas interest on reserves is variable at the target rate and so the amount of government spending changes immediately when the target rate changes.

All government spending is done by “printing money”. The deficit is difference between money creation (spending), and money destruction (taxation). This needs not to be inflationary for a very simple reason: non-government sector can save in government’s money. For example if a pension funds collect money from wage earners and buy government bonds causality is clear: financial holdings of households are increased and government had provided means for this by deficit spending both money and bonds.

J.V., everything you wrote is the standard monetarist bla-bla-bla which has no connection to our reality. Money does not cause inflation. But spending may lead to inflation. Contrary to Sumner’s and other monetarists belief and understanding of financial system most spending occurs through bank deposits and not monetary base (even assuming that central banks control the monetary base). Bank deposits are, obviously, liabilities of banks, i.e. their promises. Banks can create their own liabilities in whatever quantities they want. For bankers it is very easy to promise anything.

Tom Hickey:

“Every system that claims to be scientific is based on a formal system (algorithm). The algorithm is a set of tautologies that say nothing about the world.”

This comment will probably be utterly ineffective, but the following expresses the way logicians use words.

A formal system and an algorithm are DIFFERENT concepts (albeit strongly related).

An algorithm and a set of tautologies are DIFFERENT concepts.

An algorithm is a set of formal expressions that when interpreted procedurally will yield the solution for a given problem in finite time for all possible inputs.

A tautology is an expression of propositional logic that is valid, which means that it is true for all possible attribution of the true or false values to the atomic statements appearing in it.

An equation is not a tautology. Equals, ‘=’, is NOT a logical symbol. Or, ‘\/’, and, ‘/\’, , implies, ‘->’, are logical symbols.

@ PG

Agreed. I was speaking loosely in that comment, some of the other aspects of which are loose summaries, too, but I said it was broad brush. I was addressing the objection that MMT is nothing but a bunch of identities that economists have long known about. MMT doesn’t claim to have discovered these identities. The contribution of MMT is it’s the interpretation of them in terms of a macro theory. See Peter Cooper’s articulation of this in his post, Sectoral Balances and Keynesian Causation.

The point is that the formal aspect of a science is purely syntactical and must obey syntactical rules. Sytax says nothing about the world. Semantical interpretation is required to connect the syntactical with the observable. The formal aspect of the system supplies logical rigor, and the semantical aspect supplies content and context through interpretation.

The formal aspect of a scientific theory is often called the algorithm, and its components are said to be tautologous because their syntactical truth is rule-based rather than empirically determined, that is, they follow from the formation and transformation rules. When the theory is interpreted semantically, its algorithm becomes an empirically testable model.

In the Tractatus, which is a logical articulation of the intro to Hertz’s Principles of Mechanics Wittgenstein set forth a simpler and more elegant alternative to the tack of Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica by presenting a formalization of the logic of description based on descriptive propositions and logical operators. In The Logical Syntax of Language Rudolf Carnap developed these ideas, sometimes in opposition to his understanding of Wittgenstein. But both were in agreement on the fundamental distinction between the syntactical and semantical aspects, which was presaged by C. S. Peirce in his notion of semiotics as comprised of syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics. (Wittgenstein went on to explore pragmatics in Philosophical Investigations.)

This has been the general trend of thinking since. In A New Kind of Science, Stephan Wolfram develops these insights to a new level.

Wikipedia