I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The IMF needs a budget deficit-biased head

Let Peter Costello work his magic at IMF – mounted a case for our former Treasurer (one of the worst this country has ever had) should get the baton and head to Washington. The problem is that Costello left a destructive mess in his wake and is a budget surplus obsessive. What the IMF needs is a budget deficit-biased head. The article mentioned was written by the clueless Julie Bishop who is currently the deputy leader of the opposition and their shadow spokeswoman for foreign affairs. She was previously the Shadow Treasurer until her gaffes became too much for even the conservatives to bear. Here is an assessment of her by the conservative columnist Greg Sheridan (August 22, 2009) (Source)

The opposition’s response, through Bishop, was pathetic. It was internally contradictory, unprincipled, amoral beyond even the exigencies of parliamentary hypocrisy and profoundly stupid. Bishop was a dud shadow treasurer and is now a dud foreign affairs spokeswoman. But her response on China betokens a much broader crisis for the opposition. The Liberal Party is now not so much a political movement as a collection of unemployed former ministers in search of a public service to do their thinking for them. Bishop’s press release of August 19, surely one of the dumbest press releases issued by a foreign affairs spokesperson”Which speaks to her qualifications as a referee for Peter Costello as a potential IMF chief. But Peter Costello has a public record that tells us how unsuited he would be for any senior economics role that purports to advance human welfare. Bishop claims that Costello’s “term as the country’s longest serving treasurer from 1996 to 2007?:

… is a period often referred to as a “golden age” for the Australian economy.It was the “golden age” in the same way that my profession declared that the major macroeconomic problems had been solved by the Great Moderation. Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point. Sure enough economic growth was relatively strong but not strong enough to absorb the huge pools of unemployment and underemployment left over from the 1991 recession, which was our worst downturn since the Great Depression in the 1930s. But the basis of this growth was unsustainable and the underlying dynamics that were building led to the financial crisis. Costello’s policy agenda was abandoned at the outset of the crisis and just as well. Bishop claims that Costello inherited:

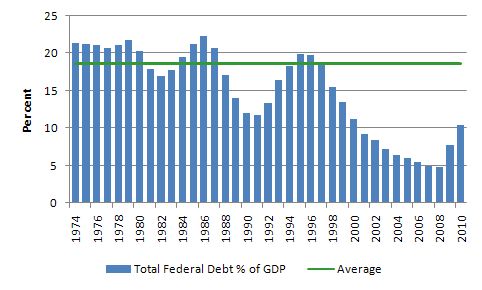

… a national budget with government debt at almost 20 per cent of gross domestic product. Economic reforms and strict management resulted in the elimination of all government debt.While focusing on the public debt ratio is an irrelevant exercise, it was already falling under the previous Hawke-Keating Labor government in the 1980s before the 1991 recession pushed it up via the automatic stabilisers. Even during that recession, the Labor government, increasingly imbued with neo-liberal zeal refused to provide fiscal stimulus and came in with some fiscal support when it was too late and unemployment and underemployment had risen to 18 per cent or so (a current US-style debacle). But the debt that Costello inherited was not problematic given and his obsession in reducing it merely deprived the private sector of income earning opportunities. Further it is an outright lie (from Bishop) to say he “eliminated” government debt. As I have written previously – Time to end the deficits are bad/surpluses are good narrative – the Commonwealth government was retiring its net debt position as it ran surpluses and were pressured by the big financial market institutions (particularly the Sydney Futures Exchange) to continue issuing public debt despite the increasing surpluses. The Treasury bowed to pressure from the large financial institutions and in December 2002, Review to consider “the issues raised by the significant reduction in Commonwealth general government net debt for the viability of the Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) market”. I made a Submission (written with my friend and sometime co-author Warren Mosler) to that Review. The upshot (see earlier blog) was that the Government agreed to continue issuing debt even though it continued to pile up surpluses. The debt was merely providing corporate welfare. There was no public goods element to the offering of public debt despite the claims from the financial institutions that it was essential for financial stability. Their claims amounted to special pleading for public assistance in the form of risk-free CGS for investors as well as opportunities for trading profits, commissions, management fees, and consulting service and research fees. Their arguments to the Review were also inconsistent with rhetoric forthcoming from the same financial sector interests in general about the urgency for less government intervention, more privatisation, more welfare cutbacks, and the deregulation of markets in general, including various utilities and labour markets. So it is a lie to say that Costello eliminated debt. What he did do was force the private sector to increase their debt holdings and in doing so was able to get enough economic growth going to generate his surpluses. It was a myopic strategy and has left a destructive legacy. For interest, the following graph taken from data provided by the RBA shows the Commonwealth debt as a percentage of GDP from 1975-2011. The green line is the average up until 1996 (after which Costello became Treasurer). You can see that the two times during this period that the federal government has deliberately tried to run surpluses (late 1980s) and the Costello era, the economy has soon after plunged into recession and the public debt ratio has risen again on the back of rising budget deficits (driven in no small order by the automatic stabilisers).

Bishop also claims that the surpluses that Costello ran provided:

Bishop also claims that the surpluses that Costello ran provided:

… significant savings invested in sovereign wealth funds to offset future pension and retirement liabilities of the federal government.Please read my blog – The Futures Fund scandal – for more discussion on this point. The point is that there were no savings. It is meaningless to say that a national government saves in its own currency. The creation of the so-called Future Fund made no fundamental difference to the underlying capacity of the Federal government to fund all of its future superannuation liabilities. The Commonwealth’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing. Therefore the creation of a sovereign fund in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations. In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system. The misconception that “public saving” is required to fund future public expenditure is often rehearsed in the financial media. In rejecting the notion that public surpluses create a cache of money that can be spent later we note that Government spends by crediting an account at an RBA member bank. There is no revenue constraint. Government cheques don’t bounce! Additionally, taxation consists of debiting an account at an RBA member bank. The funds debited are “accounted for” but don’t actually “go anywhere” and “accumulate”. The concept of pre-funding future liabilities does apply to fixed exchange rate regimes, as sufficient reserves must be held to facilitate guaranteed conversion features of the currency. It also applies to non-government users of a currency. Their ability to spend is a function of their revenues and reserves of that currency. So at the heart of all this nonsense is the false analogy neo-liberals draw between private household budgets and the government budget. Households, the users of the currency, must finance their spending prior to the fact. However, government, as the issuer of the currency, must spend first (credit private bank accounts) before it can subsequently tax (debit private accounts). Government spending is the source of the funds the private sector requires to pay its taxes and to net save and is not inherently revenue constrained. However, trying to squeeze the economy to generate these mythical “pools of funds” which are then allocated to the Future Fund as if they exist is very damaging. You can think of this in two stages. First, the Federal Government spends less than it taxes and this leads to ever decreasing levels of net private savings. The private deficits are manifest in the public surpluses and increasingly leverage the private sector. The deteriorating private debt to income ratios which result will eventually see the system succumb to ongoing demand-draining fiscal drag through a slow-down in real activity. Second, while that process is going on, the Federal Government is actually spending an equivalent amount that it is draining from the private sector (through tax revenues) in the financial and broader asset markets (domestic and abroad) buying up speculative assets including shares and real estate. That is what the Future Fund is about. It amounts to the Treasury competing in the private equity market to fuel speculation in financial assets and distort allocations of capital. However, as you can see from pulling it apart, this behaviour has been grossly misrepresented as providing “future savings” to pay for the superannuation liabilities. Say the sovereign government ran a $15 billion surplus in the last financial year. It could then purchase that amount of financial assets in the domestic and international capital markets. But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the budget would break even. In these situations, the public debate should be focused on whether this is the best use of public funds. It would be hard to justify this sort of spending when basic infrastructure provision and employment creation has been ignored for many years by neo-liberal governments. How can the government justify purchasing speculative financial assets which it has lost several billion on while holding when there were more than 9 per cent of willing labour resources either not employed at all or being forced to work less hours than they desired because of overall spending constraints in the economy? If we want to provide for a better future the Government should be spending sufficient amounts to make sure everyone has a job. That is a minimum requirement for improving the future prospects. Then it might spend some of the $60 billion it put in the speculative Futures Fund on medical research to find cures for cancer and HIV and to make our public schooling system the best that money can buy. That would be a funding the future. The Future Fund does nothing for our futures and should be unwound as soon as possible and the executives made to earn a living somewhere else! Costello’s performance in this regard was thus deplorable. He became a speculator in financial markets (losing in the process) and starved the nation of essential public infrastructure – hospitals, roads, schools all deteriorated during his period in office. Bishop says that:

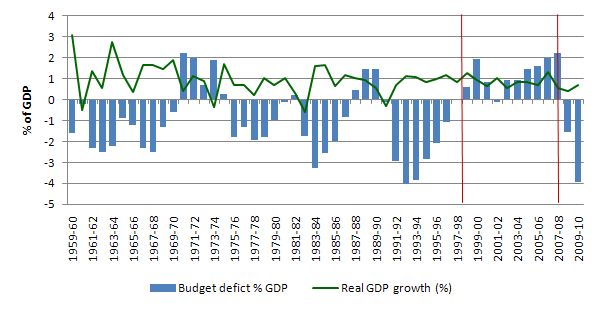

Costello’s 12 budgets included 10 surplus budgets, which resulted in two upgrades of Australia’s sovereign credit rating to AAA.The corrupt ratings agencies are irrelevant to a sovereign government. But it is important to understand how Costello achieved these demand-draining surpluses. The following graph shows the deficit to GDP ratio from 1960 to 2010 (blue columns) and real GDP growth (green line). You can see that Australia didn’t achieve relatively strong growth during the period of surpluses. It was more stable for the decade but that was a fool’s paradise. Despite the government rhetoric that the running surpluses contributed to Australia’s sound macroeconomic framework and continuing strong economic performance, the economic growth was in spite of the contractionary fiscal policy. Growth since 1996 largely reflected increased private sector leveraging as private deficits have risen. The pursuit of surpluses was ultimately self-defeating. For all practical purposes any fiscal strategy ultimately results in a fiscal deficit as unsustainable private deficits unwind. But these deficits will be associated with a much weaker economy than would have been the case if appropriate levels of net government spending had have been maintained. You will also see that deficits were the norm over this period (and for the period before that right back to the 1940s. It was common for national governments to run continuous deficits. The trend to surpluses was atypical and a hallmark of the neo-liberal period.

The household debt legacy impacted severely on housing affordability.

The Australian Senate Select Committee on Housing Affordability in Australia conducted its enquiry in 2008 and its final report – A good house is hard to find: Housing affordability in Australia – is worth reading if you are interested in this topic.

Housing affordability plunged during Costello’s period as Treasurer. The Committee found that:

The household debt legacy impacted severely on housing affordability.

The Australian Senate Select Committee on Housing Affordability in Australia conducted its enquiry in 2008 and its final report – A good house is hard to find: Housing affordability in Australia – is worth reading if you are interested in this topic.

Housing affordability plunged during Costello’s period as Treasurer. The Committee found that:

There is consistent evidence that housing in Australia has become less affordable in recent years and the number of households experiencing mortgage stress has increased.While there were housing booms all around the world during this period of deregulation, the Committee found that:

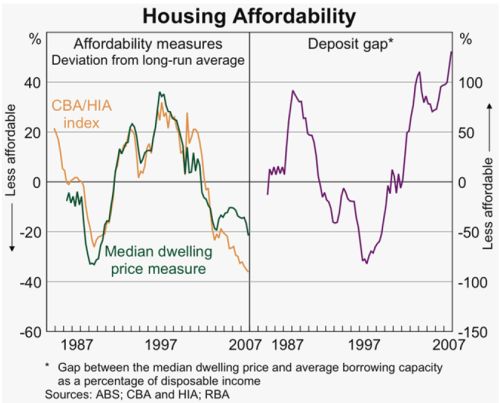

Over the past decade house prices have risen faster than incomes in a number of comparable economies. However the increase has been more marked in Australia than elsewhere and houses are now less affordable than in most comparable economies.There are a plethora of measures of housing affordability and they all tell more or less the same thing. The following graph is taken from the Report (Chart 3.3) and shows two different measures of affordability.

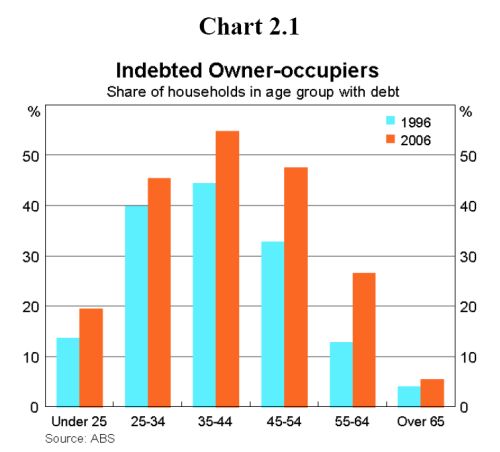

Accompanying the rising housing stress was increasing mortgage stress. This graph is taken from the Report (Chart 2.1) and shows the age-profile of owner-occupied mortgage debt at the beginning of Costello’s reign as Treasurer and around the end of his period in office.

The proportion of indebted owner-occupiers grew substantially in each age cohort during his period in office.

Accompanying the rising housing stress was increasing mortgage stress. This graph is taken from the Report (Chart 2.1) and shows the age-profile of owner-occupied mortgage debt at the beginning of Costello’s reign as Treasurer and around the end of his period in office.

The proportion of indebted owner-occupiers grew substantially in each age cohort during his period in office.

The financial engineers who were pushing debt onto all age groups also targetted older Australians prompting the Treasury to tell the Committee:

The financial engineers who were pushing debt onto all age groups also targetted older Australians prompting the Treasury to tell the Committee:

So that is a sizeable increase in the level of housing debt of older Australians and that is of interest to us in terms of retirement income policyMany indebted senior citizens were subsequently wiped out by the financial crisis – having, in some cases, mortgaged houses they already owned outright, to fund other expenditure, as the consumption binge rolled on. But at the same time, the cutbacks in public housing (in pursuit of the surpluses) were causing acute stress among poorer Australians. For example, the Select Committe concluded that:

… there is a growing pool of people who cannot access affordable housing, appropriate or otherwise. Those most at risk are often also the most vulnerable in our society, such as Indigenous Australians and people living with a disability.Leaving that legacy doesn’t appear to be what we would want for the next IMF head. Bishop claimed that Costello:

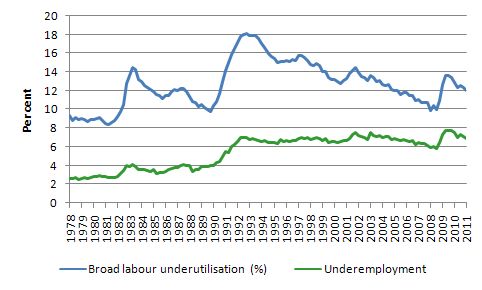

… established a system of monetary policy targeting inflation by agreement between the treasurer and the Reserve Bank that is now accepted and implemented by all main political parties in Australia.First, this is a lie. Even a casual visit to the RBA Home Page will tell you that inflation targetting began while Costello was still in opposition. For example, the RBA says that “(s)ince 1993, these objectives have found practical expression in a target for consumer price inflation, of 2-3 per cent per annum”. Second, the conduct of monetary policy over Costello’s period in office was disgraceful. The majority claim that it solved the inflation problem but it was the 1991 recession (pre-targetting) that expunged inflationary expectations. But the RBA deliberately used interest rates to create unemployment as a means of maintaining low inflation. Please read my blog – The dreaded NAIRU is still about! – for more discussion on this point. Senior bank officials stated openly that they considered the short-run lost output and rising unemployment to be minor annoyances in the quest for long-run price stability. And so during Costello’s labour underutilisation rates remained above 10 per cent although the consumer-credit-led growth saw it fall from nearly 18 per cent from the early 1990s. What Costello oversaw was an economy that increasingly generated casual, low paid jobs and by the time he left office underemployment was above unemployment and taken together was still around 10 per cent. He then had the audacity to declare the economy to be at full employment. The following graph shows the ABC measures of labour underutilisation (the sum of unemployment and underemployment) and underemployment (the difference between the blue and green lines is unemployment). It is a sorry tale.

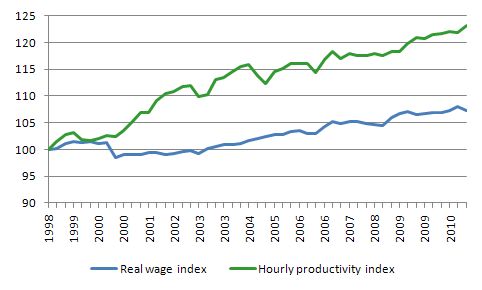

Moreover, his obsession with labour market deregulation led to a major gap between real wages growth and productivity growth emerging.

As I explained in previous blogs – the wage share in national income was constant for a long time during the Post Second World period and this meant that real wages grew in line with productivity growth which was the source of increasing living standards for workers.

The productivity growth provided the “room” in the distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation.

Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

So the wage share has fallen in many nations operating under these conditions. Thus workers could have enjoyed much higher material living standards if they could have claimed more of the productivity growth (and kept the wage share constant). Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The following graph shows the index numbers for real hourly earnings (as before) and the labour productivity (100 = September 1998). I used the National Accounts measure of GDP per hour worked market sector to align the productivity measure (hourly) with the earnings index. The graph is from the September quarter 1998 to the March quarter 2011.

So this is broadly Costello’s era as Treasurer. The modest real wages growth over this period (as the neo-liberal deregulation of the labour market and suppression of unions was juxtaposed with entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment) has lagged well behind labour productivity growth. Over this period there has been a systematic redistribution of national income to profits at the expense of workers.

The only way private consumption was able to growth as strongly as it did over this period was because the financial engineers (aided and abetted by lax regulation) convinced households to take on record levels of debt. Further, without this credit binge the economy would have slowed dramatically and the federal government would not have been able to run the surpluses for as long as they did. The Australian economy would have hit the US post Clinton surpluses recession as well.

Moreover, his obsession with labour market deregulation led to a major gap between real wages growth and productivity growth emerging.

As I explained in previous blogs – the wage share in national income was constant for a long time during the Post Second World period and this meant that real wages grew in line with productivity growth which was the source of increasing living standards for workers.

The productivity growth provided the “room” in the distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation.

Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

So the wage share has fallen in many nations operating under these conditions. Thus workers could have enjoyed much higher material living standards if they could have claimed more of the productivity growth (and kept the wage share constant). Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The following graph shows the index numbers for real hourly earnings (as before) and the labour productivity (100 = September 1998). I used the National Accounts measure of GDP per hour worked market sector to align the productivity measure (hourly) with the earnings index. The graph is from the September quarter 1998 to the March quarter 2011.

So this is broadly Costello’s era as Treasurer. The modest real wages growth over this period (as the neo-liberal deregulation of the labour market and suppression of unions was juxtaposed with entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment) has lagged well behind labour productivity growth. Over this period there has been a systematic redistribution of national income to profits at the expense of workers.

The only way private consumption was able to growth as strongly as it did over this period was because the financial engineers (aided and abetted by lax regulation) convinced households to take on record levels of debt. Further, without this credit binge the economy would have slowed dramatically and the federal government would not have been able to run the surpluses for as long as they did. The Australian economy would have hit the US post Clinton surpluses recession as well.

So when Bishop claims that:

So when Bishop claims that:

With outstanding economic and leadership credentials, Costello has a proven and enviable track record and a deep understanding of the Asia-Pacific region.I give up and have a laugh. Conclusion It is always curious to me that the most vehement defenders of the capitalist system deny its basic properties when it comes to discussing the role of governments. We are seeing that exemplified in two ways at present – in the EMU crisis and in the fiscal austerity narratives. First, in a capitalist system we consider private investors trade off risk and return. All investment (other than in risk free government bonds) carries risk. We accept that the system delivers returns commensurate with that risk. So why when the results of taking too many risks are unpalatable to the big banking conglomerates in Europe (and elsewhere) do these “defenders” cry out for government bailouts. Why do we allow profits to be privatised and losses to be socialised. It is just risk and return playing out in the Europe at present. The Greek government, for example, should stop imposing losses on its citizens as a way of protecting the gains of corporate interests throughout the rest of Europe. Second, Costello was a budget surplus obsessive. His persuasion is the anathema of what is required to provide some leadership to the IMF and turn it back into being a positive force in the world. What is needed is a deficit-biased head. Why do we accept the nonsense from conservatives that budgets are dangerous and have to be reigned in? If we understand how budgets work we would know that the private sector spending decisions largely determine the budget outcome. If we really believed in the primacy of private choice why would we seek to deny that by imposing fiscal rules which constrain government and impose costs on the private sector? Why wouldn’t we just consider two parameters as being important – full employment and private choice. Then the budget outcome would be whatever was required to maintain full employment in the face of fluctuating private spending. We would know that when private spending was strong the budget deficit would fall and vice versa. But in advocating fiscal austerity we are thwarting the capacity of the private sector to realise its saving desires. If the government deliberately reduces its contribution to aggregate demand below that required to fill the private spending gap that private saving creates (and current account deficits) then the negative impacts on overall production and income generation will deny the private sector the realisation they desire. The declining income reduces the capacity of the private sector to save. So fiscal austerity is a denial of private choice. Please read my blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point. Costello is an arch-type neo-liberal who is totally unsuitable for public office. That is enough for today!]]>

Dear Bill,

Have not been able to access the RSS feed for a few days? The error message is

XML parse failed (4:L908:C268): not well-formed (invalid token)

The validation read-out says:

Sorry – This feed does not validate.

line 908, column 268: XML parsing error: :908:268: not well-formed (invalid token)

In addition, interoperability with the widest range of feed readers could be improved by implementing the following recommendations.

line 492, column 0: content:encoded should not contain link tag

line 493, column 0: content:encoded should not contain script tag (2 occurrences)

Just wondering if it’s my reader (Awasu) or a problem in the feed?

Thanks,

jrbarch

PS. Always thought the Howard govt. was a ‘Punch & Judy’ show; the present lot joyless!

I’ve only reached the introduction…..but Peter Costello? What a joke! They guy who couldn’t see a mining boom right under his nose, and the same guy who wanted to buy back all government debt in the early 2000’s (at generational lows in interest rates) and sell Telstra (whose price had been completely torched). He’s not fit for a job in asset allocation let alone an international institution of dubious repute.

Right….back to article….

“Costello’s performance in this regard was thus deplorable. He became a speculator in financial markets (losing in the process) and starved the nation of essential public infrastructure – hospitals, roads, schools all deteriorated during his period in office.”

-I can kind of see how if a nation has a short term windfall, then a sovereign wealth fund could allow subsequent gov deficit spending to have less of a currency weakening effect (for better or worse) BUT the idea that all nations could simultaneously benefit from them all having sovereign wealth funds is bonkers. In effect it amounts to trying to move time into the future.

In 1997 Peter Costello sold off 167 tonnes of the Reserve Banks gold reserves at around $450 an ounce.

Today, the price of gold is around $1500 an ounce.

Yep, he’s a genius alright.

Quotes from Europes’ favorite IMF candidate (Google translated from French):

August 17, 2007, press conference

“The French economy is based on solid fundamentals that are […] I can not conceive today of contamination in the global economy”

August 17, 2007, in “Le Parisien”

“This is not a crash […] We are now witnessing an adjustment […] a financial correction, certainly brutal but predictable”

November 5, 2007 on “Europe 1?

“The real estate crisis and the financial crisis does not seem to affect the U.S. real economy. There is no reason to think we will have an effect on the French real economy ”

December 18, 2007, on “France-Inter”

“We will certainly have side effects, in my opinion measured. [It is] largely excessive to conclude that we are on the verge of a major economic crisis ”

January 22, 2008, on “Europe 1?

“[A crash?] Avoid spectra words, words like that angst […] I think we saw a sharp correction in Asian markets, Europe in the wake”

February 10, 2008, the G7 in Japan

“We do not expect a recession in the case of Europe”

February 11, 2008, in “Le Figaro”

“If the United States should avoid a recession, growth will be very low. Europe will also be affected. ”

March 26, 2008, press conference

“The international environment is difficult […] The current volatility of exchange rates and the dollar level is a risk to our growth”

1 July 2008, in “Le Figaro”

At the edge of the French EU presidency, wants to remain as Lagarde the French minister had allowed Europe to “avert the financial crisis after”

September 15, 2008, on “Europe 1?

“All the banking authorities, the Treasury, central banks have acted in concert for several days, the mechanisms are in place, there is no panic on board”

September 16, 2008, press conference

“[The crisis will] impact on employment and unemployment [for now] or proven or quantifiable”

September 20, 2008, press conference

“The big systemic risk that was feared by financial markets which has led them down a lot in recent days is behind us”

September 21, 2008 on “Europe 1?

“I’m not euphoric, just as I was catastrophic […] The crisis is far from over”

Just a few months before the bursting of the subprime bubble, in a NYT article titled New Leaders Say Pensive French Think Too Much, she is reported to have said:

“All these French bankers” working in London and “all these fiscal exiles” taking refuge from French taxes in Belgium “want one thing: to come back to France,” she said. “To them, as well as to all our compatriots who are looking for the keys to fiscal paradise, we open our doors.”

Prophetic, as the daily mail puts it in 2009: “French city workers flee financial chaos in London and return home to ‘£70,000 unemployment benefits'”.

I think you should concentrate more on wealth/income inequality, as in:

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t plus dissavings of the lower and middle class

IMO, that means the solution to too much lower and middle class debt owed to the rich is not more gov’t debt owed to the rich. This is throwing off the retirement market.

Here is an example of above:

finance.yahoo.com/banking-budgeting/article/112791/cash-returns-apple-google-microsoft-wsj

It occurs to me that private-public partnerships that privatize profits and socialize losses can be used as an effective fiscal policy tool if the policy makers have an accurate understanding if MMT perspectives. It seems to me that if spending is spending, government subsidy can be used as a stimulating tool if properly targeted. Thoughts? Thanks.