I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

We’re sticking to our strict fiscal rules

I am travelling today and have commitments which will take me into the night. So I have limited blog time. But there is always something to say and while I might say the same thing often I figure that there are thousands of commentators to my one who all say the same (different) thing every day. Anyway today you will learn that the Japanese government can call on the central bank to buy its bonds whenever it wants. You will also learn how crazy the British government is and how obsessive compulsive behaviour locks a nation into slow growth and entrenched unemployment. We’re sticking to our strict fiscal rules – no matter what! Simple conclusion for today – the budget madness continues.

There have been a bevy of commentators recently saying that Japan’s central bank is barred by law from directly purchasing primary issue bonds of the Japanese government. The insinuation is that the Japanese government is truly at the mercy of bond markets who will eventually foreclose on them and refuse to lend any money.

The reality is different. The Japanese government is only “at the mercy” of the bond markets if it wants to be – just like all governments which issue their own currency. The intrinsic characteristics of the fiat monetary system make it possible for the government to spend whenever it chooses without recourse to finance. That is the basis status of a sovereign government.

Under pressure from conservatives etc, governments erect an array of voluntary constraints to make it politically harder for them to run deficits. Please read my blog – On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose – for more discussion on this point.

These constraints work to limit government net spending as we have seen over the last 40 years since the Bretton Woods system collapsed and governments were free to spend what they liked (courtesy of the fiat monetary system). In the current recession, while governments responded with fiscal stimulus packages they have been only just enough to stop the world from slipping into depression.

At a time when governments should be increasing their discretionary net spending they are now moving to cut. The legacy of that madness is the persistently high unemployment and the growing numbers of long-term unemployed.

Anyway in a statement made by the Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa to the Japanese Diet (Parliament) yesterday (March 23, 2011) we learned that under Japanese law, the central bank only needs the permission of the Diet to push Japanese government bonds directly. That is the Ministry of Finance spends and the central bank credits relevant bank accounts. Bond markets – cold-shouldered.

The law allows for this under “extraordinary circumstances but this is determined by the Diet.

And perhaps that is why the bond markets are happy to buy Japanese government debt at low yields – they know that if they don’t the central bank will!

But in that context, the statement from the BOJ Governor that Japan’s “fiscal situation is very severe” and that the “investors’ trust in the country’s policy makers is keeping bond yields low” doesn’t make much sense to me – other than being a conservative political statement aiming to advance ideological ambitions.

He was quoted by Bloomberg as saying:

If a central bank starts to underwrite government bonds, there may be no problems at first, but it would lead to a limitless expansion of currency issuance, spur sharp inflation and yield a big blow to people’s lives and economic activities.

Limitless in relation to what?

As long as the budget deficits are filling the spending gap left by external deficits and private domestic saving (as a sector) and the economy is not over-stretching the real capacity of the resource base to respond to this nominal demand in real terms (that is, by producing output) the statement by the BOJ Governor is to be interpreted as conservative ideological rhetoric.

There is no problem … at first … at second … and forever … if government deficits (facilitated by the central bank crediting bank accounts on behalf of the treasury and accepting some treasury paper for accounting purposes) continue to fill spending gaps in this manner.

So all those commentators who think the earthquake and tsunami has presented the Japanese fiscal crisis – by which they mean – the government cannot afford to pay for the reconstruction – should now desist. The “problem” that has been keeping them awake at nights is solved.

If the bond markets are sick of the corporate welfare that the issuance of government bonds provides them (that is, a risk-free annuity), then the Diet just rings up the BOJ and tells them to keep crediting those bank accounts.

The real problem for Japan will be the lost capacity that has resulted from the damage. This might limit the speed in which the economy can grow for a while. It is unlikely that there will not be enough real resources available to actually facilitate the reconstruction. If there are then the Government will free to purchase and mobilise them.

End of story!

Please read my blog – Earthquake lies – for more discussion on this point.

My mate Warren Mosler has a tag on his E-mail signature line about the US that goes like this:

Because we believe we can be the next Greece, we continue to work to turn ourselves into the next Japan.

Today his comment on the Bank of Japan governor’s statements were:

Because they think they could be the next Greece they *are* Japan.

Comedy segment over! (I laughed).

But while we might laugh the actual reality is tragic. In response to the BOJ governor’s admission that the central bank could directly by government debt the Vice Finance Minister Fumihiko Igarashi told the Diet that the government:

… needed to be “cautious” in considering whether to have the BOJ make direct purchases.

He said that the Government is instead considering a mix of “Bond sales, cuts to other spending and tax measures” to pay for reconstruction. This is in the context of an economy with very significant non-government savings and stagnant growth and an expectation that its export performance will plunge in the coming year because factories are closed and infrastructure damaged.

I guess that is why they *are* Japan.

British budget 2011

Which brings me to my one word analysis of the UK budget – appalling.

And then a few more words … Looking through the Budget documents – you soon get drowned in neo-liberal terminology.

We read that an aim is to “keep debt and debt interest paid by the Government – and ultimately the taxpayer – lower than would otherwise have been the case”.

When I would say that the “taxpayer” never pays for this interest but some taxpayers receive it as income!

Again, the UK Treasury doesn’t seem to understand the monetary system it operates within. Consider this example:

Events in the euro area periphery illustrate the problems that can be caused by heightened market concerns regarding fiscal sustainability. A key lesson from recent events is that once market sentiment turns against a sovereign issuer, it is extremely difficult to regain. Retaining fiscal credibility is therefore critical.

There is no “key” lesson here for anyone. Britain rejected an invitation to join the Eurozone (a wise decision) so it retained its currency sovereignty. The problems that “non-sovereign” Eurozone governments are having raising funds has no relevance for Britain.

Market sentiment cannot dominate the fiscal capacity of a sovereign government.

So the above statement is not only inapplicable but also plain wrong.

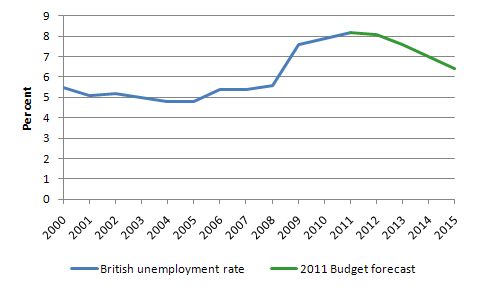

It is also clear that the whole UK Government strategy is based on very optimistic (unreal) estimates of real growth. Even with those pie-in-the-sky estimates out to 2015, here is a chart I created from their unemployment rate estimates. So they are predicting the official unemployment rate will stay above 8 per cent through 2012 and drop to 7.6 per cent through 2013.

The Budget papers don’t show the data before the crisis. This graph is from 2000 to 2015 and includes the data included in the budget estimates (green segment). Even after five years of the Government’s so-called “growth” strategy (joke!) the unemployment rate would still be around 2 percentage points above the pre-crisis level.

So the Government is abandoning its responsibility (under ILO and UN human rights treaties to which it is a signatory) for providing jobs for all. It is allowing millions to wallow in joblessness for years.

The problem is that the progressive voice is mired in contests with the conservatives about making “fiscal consolidation” fairer.

Dear Progressives,

The British economy needs further fiscal stimulus. Without it, millions will remain jobless. Go figure.

best wishes

bill

I could go on analysing the UK Budget but time isn’t in my favour today. The message should be clear.

And if you thought Australia was ahead of the pack …

Think again.

As background, the latest Australian Labour Force data was not encouraging. Here is my blog on that data release – Australian labour market – mixed signals – but subdued overall.

The December quarter National Accounts were also not very encouraging. Here is my blog on that data release – Australian National Accounts – I wouldn’t say the economy is great.

There is an array of other economic data which indicates the Australian economy is slowing to a crawl and unemployment and underemployment will remain high for the foreseeable future.

The mining sector is booming because our terms of trade (export prices relative to import prices) are booming. But that sector is not adding to overall real economic growth (given net exports are still negative).

The withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus is exposing how weak private spending is at present. Households are carrying record levels of debt (relative to disposable income) and are trying to increase their saving ratio to provide some risk management.

Private capital formation (investment) is mixed but overall weak.

So growth is slowing …

Then we read a – Ministerial statement to the Australian Parliament from yesterday (March 24, 2011) where the Treasurer outlined the following extraordinary logic:

Mr Speaker, it is against the backdrop of these natural disasters that we will spend the coming weeks putting the final touches on our fourth budget.

Recent events – both here and abroad – will make a difficult task even more difficult. The early years of the budget estimates will bear the brunt of the rebuilding and recovery costs, and Government revenue will also take a hit from weaker growth in the short term.

But keeping our budget on track to return to surplus by 2012-13 is the right economic strategy for an economy which is expected to be pushing up against its capacity over the coming years. Just as it was the right thing to step in and support demand during the global recession, it is the right thing to do to step back when private demand is strengthening.

We’ve already put in place around five and a half billion dollars in savings to meet the cost of rebuilding from the floods and cyclone. And we’re sticking to our strict fiscal rules, including our cap on real spending of 2 per cent or less in above trend growth years. We understand that this will mean that we need to do a lot of things in this Budget that won’t be popular, but they’ll be the right thing to do.

That is how far askew things have become in the public debate. This statement is from one of the most senior politicians in our land. It was an amazing example of budget lunacy. He is exhibiting obsessive compulsive behaviour which will damage our nation.

First, there has never been any economic or financial logic in pursuing a budget surplus by 2012-13. That was just a political imposition so the government could ward off the conservative claims that it was reckless in introducing the stimulus packages.

The facts are clear:

- the external sector is rarely in surplus – so typically drains expenditure.

- the private domestic sector is carrying too much debt which has to be divested through saving.

- the labour underutilisation rate (fancy name for wasted available labour) is 12.2 per cent at present.

- core inflation has been falling and at any rate the current cost pressures (energy and food) are not sensitive to monetary policy.

Taken together, the import of these facts is obvious.

For growth to continue at a pace that is sufficient to reduce the appalling wastage rate of our precious labour resources, net public spending has to be positive and larger than what it currently is.

Net public spending … is the same thing as … the … budget deficit (lets not say it aloud)!

The government is claiming that we will be at full employment and capacity by 2012-13. From what means? Not at the rate we are going at present. Growth is well below trend at present and private spending remains subdued.

The idea that you would move to achieve a surplus by 2012-13 by cutting net public spending now is irresponsible given the context of the economy.

The Government should have maintained the stimulus with appropriate design to allow the spending to decline as privately-motivated growth picked up. Then if by 2012-13 we were getting a net positive contribution to growth from the mining sector and/or private domestic spending sufficient to drive growth and reduce unemployment and underemployment – the Government might be justified in saying a budget withdrawal is necessary.

I preface that statement by noting that private debt levels have to drop to provide some financial stability to that sector. This will require a saving effort over many years (given the time that the households and firms overall binged on credit). That process has to be supported by government deficits given that net exports are not sufficient to drive the necessary income growth.

There is nothing coming out of the Treasurer’s office that suggests he understands any of that. His stubborn entreaty that “we’re sticking to our strict fiscal rules” just sounds like obsessive compulsive behaviour to me.

Second, the idea that because growth is faltering – and the automatic stabilisers (lost tax revenue, less saving in welfare outlays) are pushing the deficit higher – that the Government has to impose even more austerity is breathtaking … at the very least.

Horse before the cart! The budget outcome should never be a “rule” that is blindly followed. As I have noted previously, the budget outcome is not something the Government can control very easily. It can try but ultimately it is private spending decisions that determine the final outcome.

If a government pursues austerity thinking each dollar it cuts is a dollar in budget shrinkage it will typically fail. Why? Because the austerity reduces national income which impacts negatively on private spending, which, in turn, further reduces national income. The negativity of the austerity reverberates throughout the economy.

As the economy declines, the falling tax revenue and increased welfare outlays increase the budget deficit (or reduce an existing surplus). The faster the government cuts the worse the situation will get.

So the last thing you would do when there is already evidence that government revenue is about to “take a hit from weaker growth” is deliberately cut back net public spending because the projections now suggest you won’t achieve your preconceived budget goal.

Fiscal policy is a living art form. It requires sound judgement and the ability to be flexible and move with changing circumstances. Setting fiscal rules is the anathema of that reality.

It also requires us to understand that the budget outcome is part of the overall “system solution” and depends on private and public spending decisions. Trying to control an outcome is irresponsible and fraught.

The more appropriate role of government is to target real outcomes – like employment and output growth to ensure unemployment and waste is minimised. The budget will be whatever it takes to achieve those goals … and that is just fine.

“Sticking to our strict fiscal rules” is just an admission that the Treasurer has no flair.

Conclusion

I have to finish on that note.

Sovereign governments who don’t want to be sovereign – that is what this is all about.

That is enough for today!

What about Indonesia 1997?

Dear Aidan (at )

You ask about Indonesia 1997.

By asking that question you are yet to understand the fundamentals of Modern Monetary Theory which was behind my statement (questioned by you) that:

Many Asian states in the 1980s and 1990s (leading up to the crisis) maintained a system of pegged exchange rates (against the US dollar).

As you might recall, the Chinese currency was devalued by 50 per cent against the US dollar in 1994 and the yen fell by 40 per cent against the US dollar between 1995 and 1996.

This undermined the exports competitiveness of the Southeast Asian economy who were pegging against the US dollar. Have a look at the parities during this time.

Thailand was the first to go – and tried significant interest rate increases to defend the baht (via the capital account). This worsened the crisis which exposed the heavy indebtedness of the private firms and undermined the over-inflated property market. Loan defaults rose dramatically which undermined the banks. There was also significant foreign debt exposure.

Indonesia was a little different because they allowed for a snake within the peg (around an 8 per cent range) so when the yen and yuan depreciated against the US dollar their loss of competitiveness was not as large as for Thailand. When the crisis began, Bank Indonesia increased the range of the snake (to 12 per cent). They also pushed up interest rates which worsened the crisis. Eventually they could not defend the rupiah and they floated.

When the rupiah depreciated it exposed the foreign indebtedness which if you read the documents at the time will show you that the central bank had completely let go of its responsibility to monitor the foreign debt exposure which was mostly short-term – thereby creating massive liquidity problems as the currency fell.

The banking system basically collapsed.

Then they further relinquished their sovereignty by allowing the IMF to come in.

Lesson: these states were not sovereign in their own currency. Their governments pegged their exchange rates thereby tying monetary and fiscal policy. They also borrowed in foreign currencies.

best wishes

bill

Re Bill’s claim that “The British economy needs further fiscal stimulus”, one point that economic conservatives are currently putting against this idea is the current British so called inflation rate of 4.5% (compared to the target of 2%).

The answer to the latter point is that most of the so called 4.5% is the result of the 2008 Sterling devaluation and the rise in world commodity prices. These are secular or temporary phenomena, the effects of which will eventually peter out.

In other words most of the 4.5% is not really inflation at all. That is, inflation consists of CONSTANTLY rising prices, whereas most of the 4.5% is a TEMPORARY phenomenon. Or put another way, as long as the effect of the devaluation and commodity price rises do not feed thru to wage rises, the 4.5% is nothing to worry about.

Or put it a third way, restraining demand in the U.K. at the moment is fatuous in that it won’t reduce the effect of the devaluation or commodity price rises.

Seems that sooner or later all pegged currencies go tits up. How long before China blows up?

Andrew says:

If China ever blows up it will not be as a result of its currency pegging

They’ve pegged it at an artificially low level, and it’s much easier to decrease the value of a currency than to increase it. And they can easily float it any time they want to.

“The answer to the latter point is that most of the so called 4.5% is the result of the 2008 Sterling devaluation”

And the other part is a result of the VAT rises. Only a bizarre system would include a cost that actually destroys money in the figures. They may as well include income tax and make ‘inflation’ even higher.

Furthermore the 2008 devaluation wasn’t really a devaluation, but more a return to the average exchange rates of the 1990s.

Gordon Brown’s pro-cyclical boom resulted in a currency bubble as well which artificially held down the price of imports in the UK. That is now unwinding.

The only conclusion I can come to is that Brown thought that increasing the public expenditure would ‘crowd out’ the housing bubble that was forming. The sole benefit from that period then is that the UK economy from 2001 to 2008 is very good evidence against crowding out.

Bill,”The more appropriate role of government is to target real outcomes”. I doubt if this current federal government has the slightest clue as to what “real” is.

As for “outcomes” I don’t claim to see into the future but the danger signs are flashing all over the place in so many areas,not just the economy although that is a wide field.

History is replete with examples of individuals,groups and nations taking quite bizarre directions which seemingly had plenty of support at the time.It is in retrospect that we ask,what the hell were they thinking?

An aside;

A discussion about money, the fed, Ron Paul and inflation is taking place over here; http://andolfatto.blogspot.com/2011/03/ron-pauls-money-illusion-sequel.html

One of the libertarian high priests, a free banking advocate George Selgin, is commenting there. It would be interesting to see how he responds to some of the MMT points.

The subject he is addressing is nominal vs real metrics, especially wages.

Neil Wilson says:

Thursday, March 24, 2011 at 18:40

“Gordon Brown’s pro-cyclical boom”?

2005: 2.173% 2006: 2.788% 2007: 2.685%.

@Ralph

about the UK inflation rate, I understand what you are saying, although there is still a bit that I fail to understand.

I have read blogs here about how MMT deals with inflation caused by the supply side, and inflation caused by the demand side. What I still don’t get is the impact of floating exchange rates in all this.

If a government was to start spending appropriately and stop borrowing the exact equivalent of its budget deficit, wouldn’t that cause a world-wide collapse in the demand for the national currency, causing further devaluation and therefore push inflation even higher (through higher world commodity prices from the domestic sector point of view)? Or would that be only a one-off effect?

Please help, this is doing my head in!

Hi bill

Just started reading your blog but have been well indoctrinated by my older brother alan who has been educating me on mmt for years. I am also a big fan of John P. Hussman. How do you reconcile his thoughts on government spending?:

It cannot possibly help that the Fed continues to pursue an aggressive policy that drives short-term interest rates to negative levels, which predictably encourages commodity hoarding around the globe, and the unintended consequences that result.

Thanks.

Ralph: The answer to the latter point is that most of the so called 4.5% is the result of the 2008 Sterling devaluation and the rise in world commodity prices. These are secular or temporary phenomena, the effects of which will eventually peter out.

Could be. But inflation feeds itself especially if you pursue a fiscal expansion. Not the case of the UK though.

Andrew: Seems that sooner or later all pegged currencies go tits up. How long before China blows up?

Eventually everything goes tits up. You can maintain a currency peg for as long as you want if you sustain a trade surplus and keep your inflation in check. That’s what the chinese are trying to do, but despite the peg the yuan appreciated about 10% mainly because of domestic inflation.

I haven’t seen the latest polls, but last I saw a substantial number of Brits are in favor of adopting the euro.

As previously discussed, I suggest the problem is it’s not intuitively obvious to the populations of Europe that the currency is the problem.

Interest rates are low, the currency is strong, and inflation is modest.

Yes, there has been a financial crisis, but it’s not causing the inflations that many of the member nations have lived through in the past.

And it’s just ‘common sense’ that the financial problems of Greece, Ireland, etc. were caused by the, corrupt, irresponsible, pandering, etc. political leadership. And now the populations are paying for those mistakes.

So the anger is directed towards the political leaders, who are replaced with new leadership pledged to being ‘fiscally responsible.’

And are now making it all worse in real terms

While the real culprit, the currency arrangements, are not even a consideration

warren,

The Angus Reid poll of Dec 2010 showed 80% would vote in favour of retaining the Pound Sterling.

48% of Brits would vote to pull out of the EU given the chance, with only 27% would vote in favour of it.

Tristan,

If the Government stopped issuing bonds the results would be similar to the QE process. Which in the current circumstance does not appear to have a severe inflationary effect. The owners of bond are generally risk averse. You might see more bidding for low risk debt driving yields down. Otherwise the money will just sit in bank reserves accepting whatever overnight interest is offered by the central bank. Some MMT commentators suggest the effects of QE on currency and commodities was influenced by sentiment I.e Trading desks used erroneous quantity of money theories to extend the run on their prior conceived trading strategies. In any case there would be a one step impact from the initial event. After that inflation levels would be determined by the usual factors. Spare capacity in the economy, Government spending, tax policy and overnight interest rate settings.

I believe the central bank could easily be done away with if policy allowed interest rates to fall to the natural rate of zero. We can look at the BOJ, what functionality do they add to the system? Interest rate of zero is effectively not issuing Government debt at all.

Politically the fate of the bond markets are tied to the fate of private pensions. As planning for retirement is a high want in the hierarchy of human needs it would be a mother of all battles to try and change the system. I would try to implement a state superanuation scheme and absorb the money from pension funds before tackling the bond market. Corporate welfare would be an easier target to attack than pensions. Just a pipe dream, not gonna happen in my lifetime 🙂

Andrew, fixing rates permenantly at zero is an interesting thought experiment. According to Krugman’s “inflation expectation” logic, this would be the ultimate in central bank irresponsibility and hence would immediately send inflation soaring. Would it really?

Max,

I haven’t read the inflation expectation theory but anything with the terms “expectation theory” sounds a crock of shit to me. Future expectations of humans can be shaped by so many variables it could not be predictable. The answer is a big fat “it depends”.

If the indebted have reached their capacity to service debt, through regulation or dare I say market forces. Inflationary credit expansion should be muted right? If there is ample spare capacity in the economy, inflation should not be a major issue.

If the economy is at full capacity and you allow banks to double ecredit card limits every month, you might see inflation.

To add on, the rates at which private individuals borrow for investment would have to be greater than 0% to prevent asset prices reaching infinity. This can be managed through conventional risk management. It’s just the Government would pay 0% on reserves.

Max: The observation that interest rates and price levels/inflation tend to be positively, not negatively correlated is called Gibson’s paradox, the name due to Keynes. As usual, the mainstream gets things exactly backwards.

Central Banks raise interest rates when inflation rises. It’s obvious there should be a positive correlation.

Where is the paradox?

for some entertaining w/e reading – http://www.cps.org.uk/cps_catalog/Five%20Fiscal%20Fallacies%20L.pdf

I just had a look at how profligate the UK was during the nominated 1997-2008 period….it averaged a deficit of just over 1%….

I love how regulatory reform (bungled) was blamed for the UK’s own crisis -ie. the very success of the conservative movement to lower the regulatory bar in favour of “the market” is now someone else’s fault…

….”Meanwhile, and because both fiscal and monetary policies had discouraged saving, the escalation in mortgage, consumer and corporate debt sucked in huge borrowings from overseas.”……..what? deficit should’ve been larger, you say??? He doesn’t seem to have noticed either that the larger deficit came AFTER the GFC. Sharp.

On running Budget Deficits…….”Anyone who believes this understands neither the debt markets nor the exponential function.” The author then launches into a chart spanning the next 30yrs to highlight interest expense. When anyone does this, I’m always reminded of the early 90s (when it was thought surpluses would never be seen again) and the early 2000s (when it was thought deficits would never be seen again). Terrific stuff.

He even counts QE as stimulus along with govt spending. Top o’ the pile.

You get the picture….

At least I’m drinking a Boag’s while reading…..otherwise my time would truly have been wasted!

Central Banks raise interest rates when inflation rises. But why? In the belief that this counters inflation, that there is a negative correlation, while the evidence is that this exacerbates inflation & instability. Keynes’ influence probably led to successful low-interest anti-inflationary policies in the US & UK during WWII. The wiki article talk page has more discussion and refs, from Geoffrey Gardiner.

“Tristan Lanfrey says:

If a government was to start spending appropriately and stop borrowing the exact equivalent of its budget deficit, wouldn’t that cause a world-wide collapse in the demand for the national currency, causing further devaluation and therefore push inflation even higher?”

Foreign governments accumulate foreign currency reserves by buying up reserve currencies in the FX markets and they could still accumulate these reserves if they choose to and held them in a similar way that banks keep excess reserves.

The causality here is not that debt issuance causes demand for currency, but that demand for currency causes need to run budget deficits.

Hi Bill,

Enjoying reading your posts. I have just discovered MMT through blogs like this one and it has really changed my mind about the current debate in politics about budget deficits (I am in the UK). However, I have asked the Bank of England if they could buy bonds directly from the Treasury, and if not, why not? This is the response I got:

” If the Bank of England bought government debt to cover the gap between the government’s tax income and its spending commitments, i.e. . to finance the budget deficit, it would be a violation of Article 123 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

If this kind of operation were to take place, it would be inflationary.”

Article 123 of the Treaty to which I was referred says this:

” Overdraft facilities or any other type of credit facility with the European Central Bank or with

the central banks of the Member States (hereinafter referred to as ‘national central banks’) in favour

of Union institutions, bodies, offices or agencies, central governments, regional, local or other public

authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of Member States shall be

prohibited, as shall the purchase directly from them by the European Central Bank or national central

banks of debt instruments.”

I understand this could be an unnecessary constraint, but given that the UK has to abide by this, does it take away any sovereignty of the UK to create money by prohibiting such an action?

Also, on the point about inflation, from what I have read on MMT, in a situation when an economy is operating below full capacity, creation of money for spending on the real economy will not be inflationary up to the level of full employment. Am I correct in thinking this or is the guy at the BOE who replied to me right?

Sorry if these are dumb questions, I am an MMT newbie.

Ben,

MMT position is that government deficits do not need financing because sovereign governments are currency issuers. Taxed money do not go anywhere, it is just reduced from bank accounts. All spending is done similarly just by marking up numbers in bank accounts. Deficit spending add to the money supply in itself.

What Bank of England is saying in that reply is that they believe in exogenous money theory, while all evidence points that the endogenous money (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endogenous_money) theory is true. In essence they believe that having a excess reserves in banking system can cause huge upsurge in lending, while endogenous money theory states that banks are not constrained in lending by the amount of reserves.

Even if exogenous theory were true it would not nullify main MMT conclusion that monetarily sovereign governments are not operationally constrained in spending.

Aren’t they just saying they are bound by Article 123 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, as any other EU member? That is, they are not really monetarily sovereign, although the pound floats wrt to the Euro.

Currency issuers do not need financiers, be it central banks or private banks or whatever, because they do not actually borrow. They issue assets, new money and bonds in this case. What we call government debt is actually stock of publicly issued assets.

That has nothing to do with what the BoE is saying.

“If this kind of operation were to take place, it would be inflationary”

Ask them how.

Ben,

While Article 123 may apply to the UK as well (according to you/BoE correspondence). there is another article – article 122 which provides relief. I believe it was Article 122 which was applied when the ECB started purchasing government bonds in the Euro Area (though from open markets).

Bonds are not purchased by the Bank of England directly because mainstream economists think of this act as leading to inflation and hence forbidden and/or strictly restricted as your correspondence also says.

The UK HM Treasury can take a draft at the Bank of England under extreme market conditions – the “Ways and Means Advance” provided by the Bank of England by using Article 122.

Government expenditures lead to higher income and wealth for the private sector and they will purchase government bonds because private sector securities are imperfect substitutes.

Even in the case of the Euro Zone nations, the ECB can provide some relief for nations but cannot stop this from becoming increasingly expensive to finance their (nations’) obligations, the process is stopped by austerity. At least it is hoped by them that that problems will go away but it comes with a tremendous loss to the employment and demand situation.

The ECB can use Article 122 as long as it wants! And so can the Bank of England and the Her Majesty’s Treasury use it under extreme market conditions.

Hi All,

Thanks for your replies to my questions. I think I may be misunderstanding this somehow. If the Government just creates money by marking up accounts (creating new assets), doesn’t there need to be a corresponding liability somewhere in the system? I thought this was done by selling bonds directly to the central bank i.e. by crediting the Treasury’s reserve a/c at the central bank and debiting its securities a/c.

Ramanan, but doesn’t article 123 mean that the UK is in fact not monetarily sovereign like the euro countries,

although the UK can devalue the pound wrt to the euro?

doesn’t article 123 mean that the UK is in fact not monetarily sovereign

Article 123 is just writing on a piece of paper.

Politically it would be straightforward to bypass. You would do it anyway and if any EU countries got shirty you would use it as evidence of those nasty Europeans preventing the sovereign UK government from improving the lot of the UK people. And then use it to threaten a referendum on withdrawal from the EU (which has 48% support at present).

A short conversation like that would ensure that a tactical fudge and a form of words would be agreed very quickly – as it has with the other countries in violation of various parts of the stability pact.

The UK can revoke any part of the EU legislation by the UK parliament making alterations to the 1972 Act that *allows* it to take precedence, much as it can revoke the ‘balanced budget’ nonsense.

MamMoTh,

Doesn’t matter. Article 123 talks of an extreme situation in which Article 122 can anyway be used. In normal circumstances, the UK Government faces no issues in financing its Public Sector Borrowing Requirement (PSBR) because higher expenditures lead to higher income and wealth for the private sector.

At any rate, my concept of sovereignty is different from the ideas here.

The UK has more issues to worry about such as the “Golden Rule”. Here is a quote from Wynne Godley from a Guardian Article Why Gordon’s Golden Rule Is Now History

More recently, the UK policy makers seem to have no idea of consequences of their actions and seem adamant to not do anything.

The Euro Zone governments on the other hand are in a situation where power has been effectively removed from them.

Article 123 is just writing on a piece of paper.

So is the whole legal system, which is, by the way, a self imposed constraint.

My question is: if the UK is subject to Article 123 like Greece, can we say that the UK is monetarily sovereign but not Greece as is repeated in this very blog all the time or not?

That is, is there any difference between EU members which are part of the Eurozone or not?

Treaties are a little different than the legal system. Without an enforcement mechanism they are worth the paper they are written on. Not that nations ever violate treaties, no that never happens. Anyway in this case, as Ramanan points out, there is the contradictory Article which allows for such actions in extraordinary times, and the ECB has been purchasing debt directly for some time now, as we live in extraordinary times.

The difference between the UK and Greece is that the entire financial apparatus in the UK is structured around a currency in which there is still (some modicum level of) local democratic control, whereas in Greece they are subject to mechanisms that the population has no formal method of influence. For the UK to reassert its sovereignty they would not need an transition periodremoving the Euro from their financial operational infrastructure; Greece would find a move back to The Drachma 2.0 very complex and painful. Both would have to “violate” treaties to do so, but that is the nature of political economy.

MamMoth,

I do not think that worrying about overdrafts only can help someone understand the situation. For example Article 123-2 of the Lisbon Treaty can always be used.

Talking of the Euro Zone ask yourself why Greece is different from Germany.

“So is the whole legal system, which is, by the way, a self imposed constraint”

That’s called an excluded middle argument, which is a logical fallacy.

I’m sure you don’t need to stoop so low.

Ramanan: I know the difference between Greece and Germany. Germans don’t understand imports are a benefit 😉

But my question is if the UK is just as operationally constrained as any member of the Euro Zone, except for the floating pound.

Either I am being really thick, or no one answered that yet.

Neil: the legal system is a self-imposed constraint written on paper, no fallacy there.

MamMoTh,

Yes, Germany has a good balance of payments situation.

The balance of payments situation of the Euro Zone is severe because the exchange rate has been fixed and nations are unable to devalue either directly or through reliance on market forces.

Gotta rush .. will try to present an answer. I don’t think “I cannot default …” and arguments along those lines is a satisfactory answer given that its easy to show that governments do not have overdraft facilities at the central bank and/or are highly restricted.

Geoffrey Gardiner and Dirk Bezemer wrote a paper for the Levy Institute about that Artcile 123 called Innocent Frauds Meet Goodhart’s Law in Monetary Policy and describes how it affected the RBS and was ultimately ignored in the end to rescue RBS.

Link_http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_622.pdf

So is the whole legal system, which is, by the way, a self imposed constraint.

We are finding that out in the US where the financiers are twisting arms to change centuries of precedent regarding land titles in order to extracate themselves from their massively fraudulent dealings through MERS. They may get away with it. It probably depends on whether title insurers will insure such dodgy titles.

Argentineans found it out when the state defaulted on their peg and two thirds of their savings were wiped out in one day.

A move often hailed by Bill on this very blog.

I believe those who sued the government won the case but nothing happened and they will never get their money back.

The guy with the 9mm works for Warren after all.

Whether article 123 does or does not prevent the BOE from buying bonds directly from the Government is bit of a moot point because they can just buy them on the secondary market which has the basically the same effect but unfortuntately usually done at a profit for the banks.

CBs of Euro zone countries do not have this option, only the ECB does.

Hi All,

A couple of weeks back I shared some correspondance I had had with the BOE on the issue of governments creating money by selling bonds to the central bank. I asked some further questions of them and have just got back some more answers. One answer in particular doesn’t make sense to me, but I am not yet fully versed in MMT to be able to confidently say what they have told me is incorrect. Could somebody help me out with my understanding? They said:

“…if the Bank was legally allowed to give money to the government via the purchase of government stock it would not be an easy process for the government to reverse and it would be carried out as part of its fiscal policy. The government would have to raise additional money to repay the Bank most probably by increasing taxes which would be a difficult and in all probability be a long winded process.”