I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Earthquake lies

I am travelling today and haven’t much time to write and I have a day of library document searches ahead. But the input from economists over the weekend in relation to the devastating earthquake and tsunami in Japan last week has been nothing short of a total disgrace. Even as the news was unfolding the mainstream neo-liberal ideologues were out in force preaching that the Japanese government was now facing a major fiscal crisis and its capacity to deal with this event was severely limited. Imagine the reactions of the people in shock after the event to hear the news bulletins telling them that their government was crippled and unable to help. The reality is that the claims by the macroeconomists were not ground in any credible theory. It is bad enough they provide this mis-information and lies when unemployment is rising. But when thousands of people are feared dead it is nothing short of being obscene. Earthquake lies – all courtesy of our neo-liberal economist brethren.

Before the full-scale of the disaster was even contemplated and the nuclear power stations started blowing up, the economists were parading out there lecturing the World about Japan’s lack of capacity to deal with the crisis because it was already broke and was carrying too much debt.

The ABC (Australia’s national public broadcaster) coverage was basically based on the Japanese public broadcaster NHK’s service interspersed with crosses back to the ABC studio to interview some expert. The ABC were running headlines as early as Friday that there was no a worsening fiscal crisis in Japan as a consequence of the disaster. Two bank economists were regularly imposed on us via the ABC coverage claiming that Japan could not afford to borrow any more.

The written media was full of it. For example, you read in this Sydney Morning Herald article (March 14, 2011) – Seismic shock for fractured global economy following Japan earthquake – that:

And while the Bank of Japan has said that it will do everything to ensure financial stability, it has little scope to work with, given the low level of interest rates and the massive amount of debt. While disasters result in a lot of reconstruction work, the challenge for Japan will be paying for it.

This AAP article (March 12, 2011) – Japan earthquake risks fiscal crisis – was representative:

The massive Japanese earthquake has raised the chances of a fiscal crisis in the world’s third largest economy and could affect countries around the globe, analysts in Europe and the US say.

The analysts are wrong. This crisis, bad as it is, has not changed the underlying risk associated with Japanese fiscal policy execution. The problem is that if the conservatives get into the heads of the Japanese politicians the latter might start believing that their fiscal options have been reduced. The operational reality is that they have not been reduced.

The Japanese government will be able to fully provision a recovery and reconstruction, however, painful and long that might take, as long as their are real goods and services available for purchase. The constraints will be in terms of real resources and time.

The press reports were all quoting some “British consultancy Capital Economics” who must be seeking clients because they were one of the first to jump onto the fiscal crisis bandwagon. They are not backward in telling us about themselves, describing their company as the “leading independent macroeconomics research consultancy” but didn’t add where! I wondered what the geographical limits on the “leading” was. Conclusion: not very broad given their public statements.

The Capital Economics report was quoted as saying:

It may be several days before the costs of the disaster are clearer … The greater the social and economic damage, the larger the threat to the government’s ability and willingness to ward off a fiscal crisis.

I will be months before the costs in real terms are fully assessed and a lifetime for some coming to terms with the personal and social costs. But the next statement is just a straightforward lie.

What is a fiscal crisis when we are talking about a nation that is fully sovereign in its own currency? Answer: there is no meaning that can be attributed to the term.

A fiscal crisis is besetting the governments of Greece, Portugal and Spain – because they are struggling to advance public purpose in their nations and cannot raise the funds to maintain existing programs. The reason is clear: they surrendered their currency sovereignty. Only the interventions of the ECB are saving the Eurozone from total meltdown but the underlying solvency problem for the individual member states is getting worse as the days go by. The intervention of the Euro bosses is failing.

But none of that is relevant to Japan – except that their export markets might be damaged if the Eurozone collapses. Even so, that is not a fiscal crisis. It would just signal a larger fiscal intervention was called for to make up for the spending collapse.

The same predictions were bandied about after the January 1995 earthquake in Kobe. I checked back to my notes and documents for 1995 when the Kobe earthquake struck. It was clearly a major disaster in terms of infrastructure damage and personal tragedy.

The New York Times said at the time (June 6, 1995):

The reconstruction of Kobe may cost well over $120 billion, making the earthquake the most expensive natural disaster in human history.

There was certainly major economic disruption. The port was severely damaged and roads were blocked.

This report documents some of the shipping disruptions:

The docks used by the huge ships, which generally carry about 2,800 containers each, were damaged, as were the tall cranes that lift them. The bridges to the islands were also damaged, making it impossible for heavy trucks to move the containers, which accounted for up to 50 percent of Japan’s international containerized trade.

And countless other stories about the economic dislocation caused by the earthquake.

The Nikkei barely missed a beat and there was also positive economic news via the “few bright spots include the computer chip and steel industries, the latter partly boosted by rebuilding in the Kobe earthquake zone” (Source: Asia Week – July 14, 1995).

But within days of the 1995 Kobe earthquake, mainstream bank and finance economists (the cohort that usually gets every forecast wrong) were out in force telling anyone who listened that the disaster would drive the Japanese government bankrupt. Apparently the public debt level was “explosive” – around 85 per cent of GDP – well beyond the Reinhardt-Rogoff catastrophe level of 80 per cent.

At the time, the conservative Japanese economists (like Makato Yano and his ilk) aided and abetted by a bevy of US mainstream macroeconomists were preaching the Ricardian Equivalence line and pressuring the Japanese Ministry of Finance to cut back the “out of control deficit”. This led to the fiscal austerity packages in 1997 which caused the economy to double-dip.

This paper – The Japanese Economy in the 1990s – is an excellent account of the fiscal debate in the 1990s in Japan. It concluded that:

… fiscal policy supported the growth of the Japanese economy in the 1990s, but … the stimulus was insufficiently strong to realise the full utilisation of capital and labour. This is an important observation … revealing the inadequacy of public policy. The government is held responsible for inadequate employment, bad performane of business firms and the associated tragedies and unhappiness.

Perhaps more interesting to theorists is the rejection of the Barro and Lucas’s theory of the irrelevance of fiscal policy to economic growth … all economic theories … have to be verified empirically and that the theory of fiscal irrelevance can not be adequately verified by studying the Japanese economy in the 1990s. By contrast, the Keynesian theory underlying this paper can be verified.

It is surprising that the irrelevance theory has been tacitly or overtly accepted by almost a generation of economists without being empirically tested … In my view, unfortunately it has now been adopted by many intermediate macroeconomic textbooks and even some introductory ones. The author hopes that the irrelevance of fiscal policy has been rejected convincingly for Japan in the 1990s and that it will be similarly rejected by empirical tests for other countries, inviting a resurgence of Keynesian economics in the world.

The reality is that Ricardian Equivalence and the broader irrelevance of fiscal policy theories have been systematically rejected in many nations since they were introduced to the literature. The pity is that they are still being used to give “authority” to the politicians who are deliberately undermining the prosperity of their nations by imposing fiscal austerity.

In terms of Japan after the Kobe earthquake there was no fiscal crisis. The only thing that happened was that the conservatives won the policy debate and further inflicted damage on the Japanese economy. It was only expansionary fiscal policy after 1998 that returned the economy to growth and some stability.

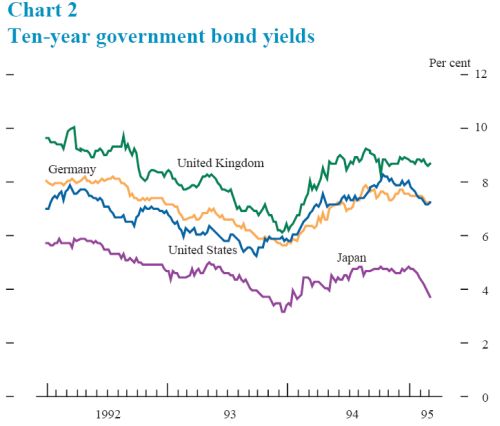

IN my notes and documents for 1995 I found this chart from the Bank of England quarterly bulletin which shows how demand for long-term Japanese government bonds soared after the Kobe earthquake. Here is the movement in yields on 10-year bonds (remember yields move inversely with demand (price)).

And since then the public debt ratio has risen to 200 per cent without any public solvency risk in sight.

But history escapes the ideologues who wheel out the same discredited theories whenever they get a chance.

The “leading macroeconomist” from Capital Economics were further quoted by AAP as saying:

The impact on local people is, of course, foremost in everyone’s minds … But the financial markets also need to consider the economic costs and the implications of the disaster for the public finances. These could be considerable … This disaster is probably not the ‘big one’ that seismologists have long been fearing …. Mercifully, the scale appears to be much less than that of the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake that hit Kobe on January 17, 1995 …

So not only are these experts in macroeconomics but also earthquake intensity appraisal. The problem is that they were so keen to get their poisonous viewpoint aired soon after the news of the disaster that they failed to understand how bad this present event will turn out to be. The news reports suggest it will be worse than Kobe. I am not a siesmologist so I cannot assess whether it was the “big one”.

But I can assess the implications for “public finances” and they are clear. The Japanese deficit will have to rise to support the reconstruction process. Its power industry is severely compromised and tens of thousands of people are likely to have died. Its transport and urban infrastructure will need massive public investments.

So unless the Ministry of Finance stops issuing debt to match Yen-for-Yen the net public spending the public debt ratio will also probably rise although the reconstruction effort if fully pursued (that is, if the deficit is allowed to expand sufficiently) will spur economic growth and so the impacts on the debt ratio will be difficult to discern in advance.

But whatever the only relevant considerations are the real and human dimensions. There is no government financial crisis facing Japan as a result of the damage. Household and firm finances might be severely impaired but that is because these entities have financial constraints. The Japanese government has no financial constraints.

Capital Economics continued to demonstrate their lack of “leading edge” insight:

A large part of the reconstruction costs will probably have to be met by local authorities and ultimately by central government, which is already struggling to bring public debt under control …

Overall, it will be that much harder to deliver a credible long-term fiscal plan in the summer if the economy is stuck in recession, the public finances are in an even worse state, and many people are still suffering the after-effects of this disaster.

At the very least, the scope for fiscal stimulus to mitigate the economic damage is much less than it was in 1995.

This is the sort of commentary that would lead me to fail a first-year (introductory) macroeconomics student. The Japanese government is not struggling to “bring public debt under control” because they have total control over the issuance of the debt. They can always decide not to issue any. Imagine the scream from the financial markets if the government there stopped issuing debt. Their pool of long-term risk free annuities would dry up and they might have to actually create some new asset themselves to price other riskier products off!

I have also noted previously that terminology such as “the public finances are in an even worse state” is totally meaningless and therefore inapplicable when applied to a sovereign nation. Budget deficits cannot be worse or better. The economy can be worse or better as measured by real GDP growth or unemployment or other important real indicators. But you can have a “large” (historically) budget deficit corresponding to “good” real outcomes (where governments use discretionary fiscal interventions to stimulate growth or “bad” real outcomes (where governments are passive or pursue austerity and the automatic stabilisers built-in to the budget framework deliver the deficits).

So there is nothing to gain by trying to say a rising budget deficit is worse. The fact is that the Japanese public finances are in a state that is largely dictated by the fluctuations in private spending. They are what they are and the Japanese government can always meet its obligations in yen.

The other point is that the statement that “the scope for fiscal stimulus to mitigate the economic damage is much less than it was in 1995” is an outright lie. The Japanese government can always introduce whatever fiscal stimulus it choose. The size of that stimulus might not be appropriate – perhaps too timid and leaving a spending gap or too aggressive and driving inflation – but it has total control. The bond markets do not dictate or limit in operational terms the capacity of the Japanese government to introduce whatever fiscal stimulus that takes its fancy.

They can provide all the necessary spending to muster the real resources necessary to reconstruct the north east of the country. Running deficit in one year doesn’t alter the capacity of a sovereign government to run a deficit in the next year. It might be that a previous sequence of deficits stimulates the economy to full employment and so deficits in the future will fall (as economic activity drives the automatic stabilisers into reducing outlays and boosting tax revenue). Governments in that situation should not try to further stimulate the economy.

But there is no constraint imposed on the capacity to run continuous deficits by a history of deficits.

Conclusion

The graphical images coming out of Japan are very challenging – very sad and open up all sorts of questions of whether it is reasonable to be a voyeur into this sort of human tragedy. But some of the images that are being displayed are totally obscene.

I refer to the sequence of interviews with mainstream macroeconomists (mostly from investment banks) who are using this tragedy as a further opportunity to mis-inform and lie to the public about fiscal policy. The same lot have been spreading the same lies about the recent natural disasters in New Zealand and Australia.

These characters not only should learn some macroeconomics but they also should learn some shame.

I have to attend to commitments now.

That is enough for today!

It gets even worse.

“The human toll here looks to be much worse than the economic toll and we can be grateful for that.” – Larry Kudlow

Larry Kudlow Devalues Human Life With Japan Earthquake Freudian Slip

(h/t digby at Hullaballo

The first response today was for the JPY to rally hard on repatriation (not surprising when japan sports a huge current account surplus) and for jgbs to rally.

One would think the easy response from the MOF would be to print trillions (ok let’s call it quant easing invested in infrastrusture rather than bonds). Sovereign state funds its expenditure, hopefully creates a little inflation and probably doesn’t result in bond yields rising too much. Rather than japanese construction workers building bridges over dried up lakes in the middle of nowhere they get to do something useful and good for the country, lowering unemployment. Seems like the best result for all.

It is just a pity most other countries don’t share the quirks of the japanese economy/marketplace to permit such actions and live to have a currency intact afterwards.

Actually there is: it is a situation where fiscal intervention would trigger a currency crisis.

Japan does not have, and is not under any threat at all of having, a fiscal crisis.

Karen Maley at business spectator also got in on the act and even dragged the US government debt position. She overlooks that the Fed can uy the bonds of the Japanese need the USD for recontruction or to buy food because farmlands have been wiped out.

All of the JPY bonds held by the public will actually help the Japanese people (including but especially the insurance companies) recover because they can “dump” the bonds on the market and BOJ can buy them up – like they have been doing today.

http://www.businessspectator.com.au/bs.nsf/Article/Japan-earthquake-debt-bonds-insurance-pd20110314-EWSRN?OpenDocument&src=kgb

To echo John Quiggin’s sentiments:

Now where were we: Oh yes – “the importance of being earnest” about CAD’s and the terrible implications.

jrbarch

“What is a fiscal crisis when we are talking about a nation that is fully sovereign in its own currency? Answer: there is no meaning that can be attributed to the term.”

Sure there is: inflation. Now I don’t think this is what most speakers have in mind (Greece is not suffering from inflation!), but it’s a meaning.

By the way, long term government bonds are not “risk free”. They have inflation risk. And that is why (contrary to what some MMTers say) government bonds do have a fiscal function, that function being to smooth the effects of inflation shocks.

The reporting on the Japanese disaster has been nothing short of disgraceful. I’m fortunate in that my wife is a Nipponophile and speaks Japanese, so she’s been translating Twitter feeds and direct news feeds all weekend. The difference in spin is marked and disturbing. Fortunately the damage has been restricted to a very small part of Japan and in the rest of the country the engineering design has done exactly what it is designed to do. We should all feel justly proud of the Japanese Engineers who have saved countless lives this week.

The reports on the nuclear reactors have clearly been informed more by Hollywood than civil engineering and physics. When you point out that a fission reactor core is designed to meltdown and that the steam release has less radiation exposure than an international flight, there are looks of bewilderment.

Public education and information are clearly working – in the ‘1984’ sense only though 🙁

It is disgusting. Peoples sense of certainty is destroyed, the displaced have lost their connection to place. Japan does not need bonds or anything else to rebuild. It is sovereign and can act in the best interests of its people. Commentators are ghoulish to suggest the world would not accept Yen for real rebuilding resources. Crimes against humanity should include lies when the deep intention is to profit from the misery created. Punchy

Even Robert Peston this morning….

“The greater financial risk for Japan is probably in its bond market, because Japan famously has the largest national debt relative to its economic output of any of the major developed economies together with a large and unsustainable fiscal deficit”

It makes you want to weep

The swines didn’t even wait for the bodies to be buried before they started chundering their self serving vitriol. As I saw the material devastation of that terrible wave, I said to myself I’ll kill the first person who says there is no money to rebuild and mitigate the suffering of the living. If there are human beings alive with a soul and a will it can be rebuilt. Fuck the bean counters.

God give me strength…. If one of those bastards comes within my reach…..

Is there some hope that a slew of hedge funds will now self destruct by going all out shorting JGB? If Japanese policy makers ignore the noise made by the bond vigilante lobby but the bond vigilantes themselves believe it enough to cause them to gamble on it, then perhaps that could be a small silver lining to this tragedy.

Well we could simply ask them if they would like for us to pay them back!

Right now we owe them this:

2. Japan

Amount of U.S. debt: $883.6 billion

Share of total foreign debt: 20.2%

I am not saying that we pay back the entire amount but we could maybe pay back 20% of the bonds that are closest to reaching maturity. That way we kill two birds with one stone, we reduce our foreign debt and we help an ally.

@Tom,

I dont think that looks like a Freudian slip by the depraved Kudlow, rather this a very revealing statement he makes. If you go back and look at it he doesnt quickly correct himself like one would with a so-called Freudian slip.

This is how he really thinks. This is an immoral statement he makes, completely depraved. This is where you get with devotion to “the church of Ayn Rand” and such depravity is rampant throughout the political right here in US.

Resp,

“This disaster is probably not the ‘big one’ that seismologists have long been fearing”

Its not the “big one” because Japan spent so much preparing for this one (in terms of both public expenditures on such things as a tsunami warning system, and the expense of earthquake code “overengineeering” embedded in construction costs). We have a pretty good idea of the difference such preparedness means. In December 2003, similar size earthquakes hit Iran (6.6 on Richter scale) and California (6.5). Iran was not prepared, California was (In the US, construction codes and emergency preparededness are handled at the state level. The Federal Government gets involved after the fact to pay for rescue and rebuilding operations).

So with nearly identical earthquakes, Iran suffered 25,000 fatalities, California, three fatalities.

http://www.geographyinthenews.org/news/article/default.aspx?id=251

This would have been the big one if Japan had fatalistically left their fate to the gods instead of spending money to prepare.

To Stone re hedge funds:

If hedge funds DON’T short the yen, then it’ll show that they don’t believe the pundits any more than Bill does!

@ Max, when Bill (and I don’t mean to speak on his behalf) says “fiscal crisis” I think he means in the financial sense of facing solvency or “funding” constraints. Japan has no solvency or funding constraints as its the monopoly issuer of its own currency (of course, the only ever default in a fiat currency was in fact Japan: it (understandably?) refused to pay its American bondholders that just nuked it – note political reasons for default, NOT economic reasons relating to solvency constraints).

Bill has always recognised the need to examine real resources, which if lacking might very well lead to an inflation risk. Having said that, a mild inflation wouldn’t be bad – it would provide increased cashflows to pay off the 1990s debt that has plauged the Japanese corporate (and less extent household) sector for the last 20 years. This was one reason we didn’t experience a Depression in the 1973-75 recession.

Max, when government bonds are referred to as risk free, it is in the sense of default risk, nothing else. Everyone know interest rates and prices can fluctuate, that’s market risk. And inflation is a risk on ALL fixed rate bonds, government, corporate or otherwise.

apj, yes, everyone knows that much, but not everyone knows what the true function of (long term nominal) government bonds is. It’s not funding, and it’s not monetary policy either. It’s inflation risk management. Inflation risk is just as real as funding risk. It would be foolish for a government like Japan to stop issuing long term nominal bonds, especially when the risk premium is low.

Max,

Are you telling us the Bond market can predict inflation 5 or 30 years down the road? I thought that notion had been thoroughly debunked.

It’s common sense to manage inflation primarily with current day settings. We only really need to keep a weather eye to the near future, 1 to 3 years ahead. Beyond that is guesswork. There are far better ways than the bond market to manage inflation. We all know the purpose of the bond market is a playground for bankers to fleece the rest of us.

andrew, of course inflation is unpredictable. That’s what makes it risky. The bond market has no idea what inflation will be. But currently it’s willing to sell inflation insurance very cheaply, so why not buy some? The time to buy insurance is when it seems unnecessary, not after a crisis hits.

Max, clearly I’m not quite getting your point about the bond mkt controlling inflation,but I’m interested in you eXpanding on how this worlds, be cause that’s the role I expect of monetary policy.

“apj, yes, everyone knows that much, but not everyone knows what the true function of (long term nominal) government bonds is. It’s not funding, and it’s not monetary policy either. It’s inflation risk management.”

You’ll really need to explain this one, if you can. Or perhaps you can convince people who bought long-term US Government debt in 1972 how well they were protected from inflation.

Is the point that if a gov “promises” to frequently issue long term bonds sold into a free market, then that commits the gov to keeping inflation low and so instills trust in the national currency. If inflation is allowed to get to say 10% and the gov issues 50year bonds sold at auction, then they might not sell them unless the yield is >10%. That threat is supposed to instill trust in gov money. Issuing a mix of inflation linked bonds and fixed interest bonds could be an even more effective method. Personally I wish the gov just made more use of taxation as the route to instilling value in gov money (since tax needs to be paid in gov money).

By the way, on the BBC Radio4 Today Program, Stephanie Flanders gave probably the closest thing yet to a BBC endorsement of MMT. She said that Japan had three times the gov debt to GDP ratio as the UK but many people believed that that would pose no problem because the Japanese gov would be able to self fund the required deficit spending by monetarising debt and that Japan would provide a test case for other developed countries.

More of the same debt crisis prognosticating:L http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lawrence-g-mcdonald/japan-debt-tsunami_b_835765.html

apj, bonds lose value when unexpected inflation occurs. They act as a shock absorber. Under a fiat currency system, government has no liquidity risk, but does have inflation risk.

Inflation indexed bonds are another story. Those have no fiscal purpose. The only purpose is to provide the public with another investment option. Maybe a good thing but not essential.

yes, I know…….though it doesn’t make much sense to me that a government would be ‘net’ issuing in a demand-led inflation. It most likely wouldn’t be required because in that case, arguably, there would be enough demand to to the point where it’s putting undue pressure on output to absorb it. G-T in such a case would probably falling. MMT is fairly clear about the inflation constraint (as opposed to a budget one). If the inflation was a supply-led one, it’s a different story. Either it’s a short-lived oil spike or something similar, or a long term structural problem that requires infrastructure spend (so that high levels of demand can actually be accomodated).

So when you say the fiscal function of bonds is to “smooth the effects of inflation shocks”, do I take it you mean the requirement to issue bonds keeps the government focussed on fiscal rectitude? ie. the attempt to protect its investors by guaranteeing low inflation?

i think max is saying that the existence of long term fixed income instruments is an automatic stabilizer vis-a-vis inflation. that is, if there is an unexpected increase in inflation (by definition not accounted for in previously issued bonds), then the price of those existing bonds falls. this takes spending power out of the economy. but then again, newly issued bonds would feature the added inflation premium (assuming the issuer adjusts), and with the higher rates they pay out larger interest payments, thereby adding inflationary pressure. bonds also allow for credit creation, whereas a system that simply pays interest on reserves does not. i’m not convinced it’s much a factor. interesting thought though, i’m curious what more informed people think of it

yeah, look, I’m not getting the connection at this point, but thanks for your input. I might just leave it for now in the absence of a more expansive explanation/ Not the first time I’ve been confused, safe to say 🙂

“i think max is saying that the existence of long term fixed income instruments is an automatic stabilizer vis-a-vis inflation.”

Yes. Note that the availability of real resources is not the limiting factor in the government meeting its promises. The issue is the distribution of wealth, which the government is not all-powerful to change (there are limits to what can be done with taxes).