Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – March 19, 2011 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The Quantity Theory of Money considers that growth in the stock of money will be inflationary. The fact that the large-scale quantitative easing (so-called printing money) in many nations in recent years has not generated inflation demonstrates that the mainstream Quantity Theory of Money is incorrect.

The answer is False.

The question requires you to: (a) understand the Quantity Theory of Money; and (b) understand the impact of quantitative easing in relation to Quantity Theory of Money.

The short reason the answer is false is that quantitative easing has not increased the aggregates that drive the alleged causality in the Quantity Theory of Money – that is, the various estimates of the “money supply”.

The Quantity Theory of Money which in symbols is MV = PQ but means that the money stock times the turnover per period (V) is equal to the price level (P) times real output (Q). The mainstream assume that V is fixed (despite empirically it moving all over the place) and Q is always at full employment as a result of market adjustments.

Yes, in applying this theory they deny the existence of unemployment. The more reasonable mainstream economists (who probably have kids who cannot get a job at present) admit that short-run deviations in the predictions of the Quantity Theory of Money can occur but in the long-run all the frictions causing unemployment will disappear and the theory will apply.

In general, the Monetarists (the most recent group to revive the Quantity Theory of Money) claim that with V and Q fixed, then changes in M cause changes in P – which is the basic Monetarist claim that expanding the money supply is inflationary. They say that excess monetary growth creates a situation where too much money is chasing too few goods and the only adjustment that is possible is nominal (that is, inflation).

One of the contributions of Keynes was to show the Quantity Theory of Money could not be correct. He observed price level changes independent of monetary supply movements (and vice versa) which changed his own perception of the way the monetary system operated.

Further, with high rates of capacity and labour underutilisation at various times (including now) one can hardly seriously maintain the view that Q is fixed. There is always scope for real adjustments (that is, increasing output) to match nominal growth in aggregate demand. So if increased credit became available and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will re

The mainstream have related the current non-standard monetary policy efforts – the so-called quantitative easing – to the Quantity Theory of Money and predicted hyperinflation will arise.

So it is the modern belief in the Quantity Theory of Money is behind the hysteria about the level of bank reserves at present – it has to be inflationary they say because there is all this money lying around and it will flood the economy.

Textbook like that of Mankiw mislead their students into thinking that there is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. They claim that the central bank “controls the money supply by buying and selling government bonds in open-market operations” and that the private banks then create multiples of the base via credit-creation.

Students are familiar with the pages of textbook space wasted on explaining the erroneous concept of the money multiplier where a banks are alleged to “loan out some of its reserves and create money”. As I have indicated several times the depiction of the fractional reserve-money multiplier process in textbooks like Mankiw exemplifies the mainstream misunderstanding of banking operations. Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted home to the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply. We have regularly traversed this point. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank.

The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

So when we talk about quantitative easing, we must first understand that it requires the short-term interest rate to be at zero or close to it. Otherwise, the central bank would not be able to maintain control of a positive interest rate target because the excess reserves would invoke a competitive process in the interbank market which would effectively drive the interest rate down.

Quantitative easing then involves the central bank buying assets from the private sector – government bonds and high quality corporate debt. So what the central bank is doing is swapping financial assets with the banks – they sell their financial assets and receive back in return extra reserves. So the central bank is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the central bank). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates. This might increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop. But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly.

How these opposing effects balance out is unclear but the evidence suggests there is not very much impact at all.

For the monetary aggregates (outside of base money) to increase, the banks would then have to increase their lending and create deposits. This is at the heart of the mainstream belief is that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment. The recent experience (and that of Japan in 2001) showed that quantitative easing does not succeed in doing this.

Should we be surprised. Definitely not. The mainstream view is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But banks do not operate like this. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

Those that claim that quantitative easing will expose the economy to uncontrollable inflation are just harking back to the old and flawed Quantity Theory of Money. This theory has no application in a modern monetary economy and proponents of it have to explain why economies with huge excess capacity to produce (idle capital and high proportions of unused labour) cannot expand production when the orders for goods and services increase. Should quantitative easing actually stimulate spending then the depressed economies will likely respond by increasing output not prices.

So the fact that large scale quantitative easing conducted by central banks in Japan in 2001 and now in the UK and the USA has not caused inflation does not provide a strong refutation of the mainstream Quantity Theory of Money because it has not impacted on the monetary aggregates.

The fact that is hasn’t is not surprising if you understand how the monetary system operates but it has certainly bedazzled the (easily dazzled) mainstream economists.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Islands in the sun

- Operation twist – then and now

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 2:

Governments pursuing fiscal austerity desire to reduce their public debt ratios. While that desire is ill-founded the strategy will achieve that end but at the cost of higher unemployment.

The answer is False.

Again, this question requires a careful reading and a careful association of concepts to make sure they are commensurate. There are two concepts that are central to the question: (a) a rising budget deficit – which is a flow and not scaled by GDP in this case; and (b) a rising public debt ratio which by construction (as a ratio) is scaled by GDP.

So the two concepts are not commensurate although they are related in some way.

A rising budget deficit does not necessary lead to a rising public debt ratio. You might like to refresh your understanding of these concepts by reading this blog – Saturday Quiz – March 6, 2010 – answers and discussion.

While the mainstream macroeconomics thinks that a sovereign government is revenue-constrained and is subject to the government budget constraint, MMT places no particular importance in the public debt to GDP ratio for a sovereign government, given that insolvency is not an issue.

However, the framework that the mainstream use to illustrate their erroneous belief in the government budget constraint is just an accounting statement that links relevant stocks and flows.

The mainstream framework for analysing the so-called “financing” choices faced by a government (taxation, debt-issuance, money creation) is written as:

which you can read in English as saying that Budget deficit = Government spending + Government interest payments – Tax receipts must equal (be “financed” by) a change in Bonds (B) and/or a change in high powered money (H). The triangle sign (delta) is just shorthand for the change in a variable.

Remember, this is merely an accounting statement. In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, this statement will always hold. That is, it has to be true if all the transactions between the government and non-government sector have been corrected added and subtracted.

So in terms of MMT, the previous equation is just an ex post accounting identity that has to be true by definition and has not real economic importance.

For the mainstream economist, the equation represents an ex ante (before the fact) financial constraint that the government is bound by. The difference between these two conceptions is very significant and the second (mainstream) interpretation cannot be correct if governments issue fiat currency (unless they place voluntary constraints on themselves to act as if it is).

That interpretation is inapplicable (and wrong) when applied to a sovereign government that issues its own currency.

But the accounting relationship can be manipulated to provide an expression linking deficits and changes in the public debt ratio.

The following equation expresses the relationships above as proportions of GDP:

So the change in the debt ratio is the sum of two terms on the right-hand side: (a) the difference between the real interest rate (r) and the GDP growth rate (g) times the initial debt ratio; and (b) the ratio of the primary deficit (G-T) to GDP. A primary budget balance is the difference between government spending (excluding interest rate servicing) and taxation revenue.

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate.

A growing economy can absorb more debt and keep the debt ratio constant or falling. From the formula above, if the primary budget balance is zero, public debt increases at a rate r but the public debt ratio increases at r – g.

So a nation running a primary deficit can obviously reduce its public debt ratio over time. Further, you can see that even with a rising primary deficit, if output growth (g) is sufficiently greater than the real interest rate (r) then the debt ratio can fall from its value last period.

Furthermore, depending on contributions from the external sector, a nation running a deficit will more likely create the conditions for a reduction in the public debt ratio than a nation that introduces an austerity plan aimed at running primary surpluses.

The austerity nations will likely see a rise in their public debt ratios arising from the negative impacts on the budget balance arising from the automatic stabilisers as their economies slow down in the face of public spending cuts.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Saturday Quiz – March 6, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3:

The Confederate government in 1861 could have eased the inflationary impact of its war spending by issuing more bonds than it did.

The answer is false.

The key is in understanding that bond sales do not drain demand.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The writer fails to understand that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

The textbook argument claims that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made.

Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet).

Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target.

Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance.

So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Printing money does not cause inflation

Question 4:

A recent Bloomberg report on the British economy says that “the government has staked its reputation on eliminating the budget deficit … by the time of the next election in 2015”. The current deficit to GDP ratio is around 10 per cent. The declining deficit to GDP ratio will signal the discretionary contraction in net public spending.

The answer is False.

The question probes an understanding of the forces (components) that drive the budget balance that is reported by government agencies at various points in time. The answer is False because there are situations that could arise (although highly unlikely) which would contradict the statement about the movements in the deficit ratio being driven by a “discretionary contraction in net public spending”.

In outright terms, a budget deficit that is equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP is more expansionary than a budget deficit outcome that is equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP. But that is not what the question asked. The question asked whether that signalled that the government is adopting a less expansionary policy – that is, whether its discretionary fiscal intent was expansionary.

In other words, what does the budget outcome signal about the discretionary fiscal stance adopted by the government.

To see the difference between these statements we have to explore the issue of decomposing the observed budget balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the budget process.

The federal (or national) government budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit or the deficit increases as a proportion of GDP doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-

Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So the data provided by the question could indicate a more expansionary fiscal intent from government but it could also indicate a large automatic stabiliser (cyclical) component.

Therefore the best answer is False because there are circumstances where the proposition will not hold. It doesn’t always hold.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Premium Question 5:

When net exports are negative, government deficits will be required if the private domestic sector is to save overall.

The answer is True.

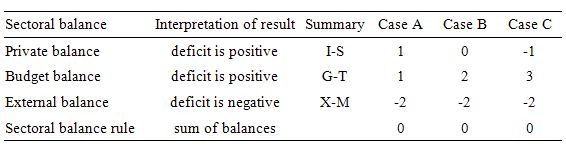

This question is an application of the sectoral balances framework that can be derived from the National Accounts for any nation.

The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

To help us answer the specific question posed, we can identify three states all involving public and external deficits:

- Case A: Budget Deficit (G – T) < Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case B: Budget Deficit (G – T) = Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case C: Budget Deficit (G – T) > Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

The following Table shows these three cases expressing the balances as percentages of GDP. Case A shows the situation where the external deficit exceeds the public deficit and the private domestic sector is in deficit. In this case, there can be no overall private sector de-leveraging.

With the external balance set at a 2 per cent of GDP, as the budget moves into larger deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance (Case B). Case B also does not permit the private sector to save overall.

Once the budget deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) the private domestic sector can save overall (Case C).

In this situation, the budget deficits are supporting aggregate spending which allows income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector but have to be able to offset the demand-draining impacts of the external deficits to provide sufficient income growth for the private domestic sector to save.

For the domestic private sector (households and firms) to reduce their overall levels of debt they have to net save overall. The behavioural implications of this accounting result would manifest as reduced consumption or investment, which, in turn, would reduce overall aggregate demand.

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms lay-off workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession.

So the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur. Given the question assumes on-going external deficits, the implication is that the exogenous intervention would come from an expanding public deficit. Clearly, if the external sector improved the expansion could come from net exports.

It is possible that at the same time that the households and firms are reducing their consumption in an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public budget balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving overall if net exports were strong enough.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

“It is possible that at the same time that the households and firms are reducing their consumption in an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

“So it is possible that the public budget balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving overall if net exports were strong enough.”

I can see how the aggregate private domestic sector saving can increase, since its one term in a balance, and independently of the balance of net exports, increasing gross exports can, for example, drive increasing investment in the export sector, which is compatible with an increase in aggregate private domestic sector saving caused the a shift to a smaller negative net exports …

… but unless the increase in net exports were sufficient to bring the net exports into surplus, I do not see how the net private savings overall, the net movement of private domestic balance sheets, can go toward the positive. So long as the level of net exports is negative, and the level of the fiscal position is in surplus (G-T<0), , then the level of (I-S) must be positive, which means in increase in net private domestic financial obligations in the period in excess of any increase in net private domestic financial assets, which is reduction in net private domestic savings … and a reduction in net savings is not saving but rather dissaving.

You define the monetary base as currency+reserves. So then QE did increase the monetary base, because the Fed bought bonds and corporate debt with newly created (out of thin air) reserves, so currency+reserves (monetary base) did increase. Why do you say it did not?

I’ve obviously missed something in the premium question.

Is it just the devious wording of the question i.e. ‘government deficits will be required’

Surely, in any one period, if all 3 sectors sum to zero there has to be a government deficit if there is a private sector surplus and an external deficit, by definition.

Dear Peter (at 2011/03/21 at 5:13)

I clearly say that QE adds to bank reserves (that is, the monetary base). The point is that it doesn’t directly increase the money supply which is the aggregate that the Quantity Theory of Money considers important. The orthodox theory believes that there is a money multiplier that defines an exact relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. Clearly that theory is incorrect.

best wishes

bill

Dear Andy (at 2011/03/21 at 5:16)

You didn’t miss anything. I put in the wrong answer by mistake. Sorry. Whenever the external sector is in deficit, the private domestic sector cannot save while the budget balance is in surplus.

Sorry.

best wishes

bill

PS for all those who achieved a score of 5/5 before I fixed the result … give yourself 4/5. Sorry for that too.

QE definitely adds to money supply

the only way it can’t is if banks are the original source of the debt bought by the Fed

which they aren’t

banks intermediate almost all the debt bought in QE; they aren’t the original source

so reserve increases are accompanied by money increases on the liability side

Thanks Bill

While I’m on a roll, can I get something cleared up?

The one to one relationship between bank money and private debt, with regard to net financial assets, seems very important in MMT.

My problem is with bad debts. It seems to me that although they the debt may written off in the accounts, there is no ‘direct’, one for one, reduction in deposits/money supply. I mean the bank do not actually reduce their own deposits as a result of a bad debt.

If this is the case, do we not need an additional sectoral balance to accomodate this when considering stock flows?

Thanks

bill seems to be running into trouble with the definition of things like money.

Is it the Quantity Theory of Monetary Base or the Quantity Theory of Medium of Exchange?

There are plenty of people that think it is the Quantity Theory of Monetary Base. scott sumner comes to mind right away.

Andy, when banks write off bad debts wouldn’t that actually tend to decrease the money supply by even more than the value of the written off debt. The limiting factors to bank created money are a multiple of bank capital and (if that is not limiting), then banks’ perceived prospects for making a profit from the loans. Bank capital is built from retained profits and written off debt is subtracted from that. I guess banks’ perceived prospects for making a profit from the loans would also take a hit from a spate of debt write downs. I have to confess that my “knowledge base” about banking is limited to reading a couple of wikepaedia entries though :).

Stone

Thanks. I’m unsure of the indirect effect through the reserve ratio. I accept Bill’s view though that lending is driven by the decisions on a) whether banks view the potential borrower as creditworthy and whether the potential borrower is willing to accept the price rather than anything to do with the level of reserves.

My real concern though is on how this affects the sectoral balances (I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0.

It seems to me that if there is no 1 for 1 reduction, or for that matter if there is a 2 for 1 reduction in the money supply i.e. by actual repayment of the debt or reduction in the bank’s own deposits when bad debts are written off then the identity does not hold, no matter how small the effect.

If this is the case, it seems to me it needs to be addressed

Andy, I hope I’m following you. When a bank actually writes off a bad debt what does it do operationally? If the bank capital is say held entirely as US treasury 10year bonds (I know in practice they hold a mix of assets), and they write off a $1000 debt- do they sell $1000 of those bonds and then electronically evaporate the $1000 into the loan write off? If the bank has part of the bank capital as cash, then they could just eliminate the $1000 from the pool of cash that they would otherwise have distributed (either by buying bonds to replace the cash, paying dividends or conducting share buybacks or whatever). Either way when a loan is written down the bank scrubs off the money. I’m probably in a total muddle about this. Some people on here actually know about this stuff and hopefully will explain.

Stone

Just to be clear are you saying they reduce their own cash account to the value of the debt or that they write off the loan against profit. Is it a balance sheet transaction or a profit and loss transaction?

Andy, -omitting my waffling- I thought bank loans create a perfectly matching deposit and debt. Writing off the debt will write off bank capital in a process that immediately, directly or indirectly, eliminates exactly the written off amount of money.

Andy, the Basel rules entry on wikipaedia says that bank capital is where retained bank profits go. So when a bank writes off debts, they loose the write offs from the profits and so have less profits to retain and so less capital. My understanding is that these profit and loss transactions in aggregate produce balance sheet transactions such that it all matches up precisely??? In the 2008 crisis the banks needed to be recapitalized by governments partly because debt write offs were cut from bank capital (as well as the capital being held in the form of assets that had falling values etc etc).

Stone

I think we may be talking about different things.

My understanding is that the key ‘net financial assets’ concept links private debt and the money supply as represented by actual bank deposits/reserves.

The write off in accounts as far as I’m aware does not affect actual bank deposits/reserves directly.

Let me try this link on you.. I’ve put an ‘A’ in front to speed things up so if you can just add a t to the ‘htp’ hopefully you can copy the link and acess it straight away.

htp://cij.inspiriting.com/?p=504

FedUp, it’s confusing but my understanding is that QE has no direct effect on the so-called money supply (M1/M2/M3). It doesn’t necessarily increase reserves either, although as currently implemented by the U.S. it does. All it’s really doing is altering the maturity structure of the government debt. But that is changing all the time even without QE as the Treasury toys with its bond issuance policy. The difference is that Treasury decisions are made with a lot less fanfare than Fed decisions.

Andy, that site seems to act up on me. It initially flashes up a question like “do bank write downs affect money supply” but then that goes and there seemed to be nothing written about it???

About your question, if money is deleted from the bank’s own account then I don’t get why that does not count as deletion from “bank deposits/reserves directly”. Money goes to and fro between the bank’s account and the personal accounts of shareholders, employees and customers depending on whether the bank activities are profitable or loss making. As such it seems to me to be part of the same pool of money and so if a bank maintains £x in its own account then when some of that is deleted it must be rebuilt by drawing down from elsewhere such as by selling bank assets or not paying dividends or staff bonuses.

Stone Thanks. I ‘ve probably confused myself into a right state.

I think I’m going to take a crash course in double entry for banks and take another look at money supply basics.

At least I think I’ve figured out there is no ‘write off’ in an accounting sense of the bad debt as the original loan is nothing to with income. It’s an asset. So there is a balance sheet transaction where the debt logically would get ‘paid’ by the bank’s own ‘cash’. In which case fine. I just have nagging doubt about it.

The joys of studying again eh?