I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Religious persecution continues

1 + 1 equals 2. The world is not flat. Night follows day (usually). You are born and then you die. Spending equals income. The mid-term elections in the US proved that religious zealots target positions of high office in our democracies. They are emboldened by a righteousness brought on by their faith. In the context of economic policy this religious fervour violates the most simple facts. The most simple story in macroeconomics that every student should have ingrained in them in the first two weeks of study is that spending equals income. It is as basic to macroeconomics as 1 + 1 equals 2 is to arithmetic. The mainstream economists know this but because it implies a role for net government spending that insults their religious passions they invent all sorts of elaborate lies and myths which purport to show that cutting spending increases it. These “proofs” are equivalent to those which try to show that 1 + 1 does not equal 2?. They are logical bereft and empirically vacant. The problem is that everyone citizen who forms the same view and votes accordingly increases the chance that their job will be next to go. Meanwhile the religious persecution of those without jobs continues.

For Australians of a certain age (early baby boomers) you will recall (perhaps) the beginnings of Australian Television (1956). I cannot. But at the inception of our TV was Melbourne ventriloquist Ron Blaskett who had a naughty little doll named Gerry Gee who thrilled children for years. I was enjoying him in the 1960s as a youngster. The doll was clever and witty and his master was always warning him to behave. The original doll was auctioned in 1998 (related You Tube coverage). There is also an exhibit at the Melbourne Museum. Here is the two of them back in the 1950s.

So what is all that about? Well Gerry used to sit on Ron’s lap who always had one arm behind the doll (controlling him obviously). So when I saw the following picture today from the UK Guardian it led me to think about that era of childhood TV – banal as it was.

The problem is that this “doll” (no sexist terminology intended) is not very clever or witty and the doll master in this case hasn’t got a clue how to lead his nation out of the mess it is in (and his policies have exacerbated).

The story (November 7, 2010) that went with the picture – G20 showdown likely over US Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing – reveals how little comprehension there is among our leaders of what is going on at present.

The Guardian article reflects a number of similar news stories since the US Federal Reserve Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced on November 3, 2010 that it recognised that “the pace of recovery in output and employment continues to be slow” in the US and “(c)onsistent with its statutory mandate” the FOMC “seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability”.

The FOMC concluded that:

To promote a stronger pace of economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at levels consistent with its mandate, the Committee decided today to expand its holdings of securities. The Committee will maintain its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its securities holdings. In addition, the Committee intends to purchase a further $600 billion of longer-term Treasury securities by the end of the second quarter of 2011, a pace of about $75 billion per month.

So another bout of quantitative easing. You get a bout of influenza when you are sick. You get a bout of quantitative easing when something else is sick and you keep believing, erroneously, that the available monetary policy tools are the cure. They are not the cure and this latest intervention will do little good although it won’t do any harm.

Which brings me to the world reaction. One word: ill-informed. Another word: manic. And another: crazy.

Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

The Federal Reserve Chairman then tried to sell the strategy in an Op Ed in the Washington Post – What the Fed did and why: supporting the recovery and sustaining price stability – on November 5, 2010.

Consistent with the message of “disappointing growth” in the FOMC statement Bernanke also said that the financial crisis had deal “a body blow to the world economy” and that:

Working with policymakers at home and abroad, the Federal Reserve responded with strong and creative measures to help stabilize the financial system and the economy. Among the Fed’s responses was a dramatic easing of monetary policy – reducing short-term interest rates nearly to zero. The Fed also purchased more than a trillion dollars’ worth of Treasury securities and U.S.-backed mortgage-related securities, which helped reduce longer-term interest rates, such as those for mortgages and corporate bonds. These steps helped end the economic free fall and set the stage for a resumption of economic growth in mid-2009.

But surely with the world still wallowing in uncertainty and low growth and high unemployment the Chairman might have given some thought to whether the “strong and creative measures” were adequate.

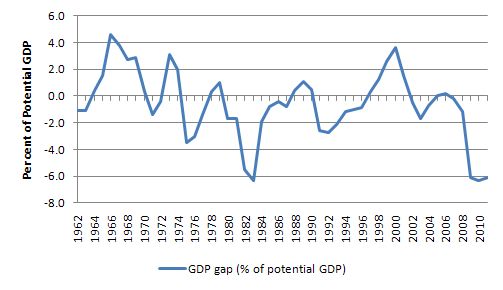

For example, the following graph shows the GDP gap for the US as a percentage of potential GDP. The data comes from the US Congressional Budget Office and the 2010 and 2011 observations are estimates. To suggest there has been significant improvement is somewhat of an overstatement.

The only reason this crisis became as large and persistent as it has is because the policy makers were scared to introduce the required fiscal policy changes – spending equals income after all (see below).

And the FOMC strategy merely reinforces this policy failure.

At the beginning of the crisis, such was the mainstream macroeconomics dominance of policy with its emphasis on inflation targetting and the misplaced belief that open market operations somehow can add to aggregate demand (they cannot), that the central banks around the world failed to quickly grasp the problem.

The problem was twofold – bank liquidity was short and aggregate demand (spending) had collapsed.

Eventually they ensured the major banks survived (by lending them fund according to demand at the policy rate). But then they started to engage in quantitative easing employing the assumption that banks were not lending because they were short of funds. This was a false assumption. The banks didn’t want to lend because they became risk averse with respect to customer appraisal.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

In relation to this continued malaise in the real economy, Bernanke noted that:

… low and falling inflation indicate that the economy has considerable spare capacity, implying that there is scope for monetary policy to support further gains in employment without risking economic overheating.

So he continues to assert that there is scope for monetary policy when it is clear that it has done very little to support aggregate spending to date. The only way that quantitative easing might influence aggregate demand was via its impact on long-term interest rates. Clearly, the FOMC thinks that bank lending is reserve constrained.

Why does he think this? He says that by buying more “longer-term Treasury securities” this approach:

… eased financial conditions in the past and, so far, looks to be effective again. Stock prices rose and long-term interest rates fell when investors began to anticipate the most recent action. Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth. For example, lower mortgage rates will make housing more affordable and allow more homeowners to refinance. Lower corporate bond rates will encourage investment. And higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion.

The point is that when people will not borrow because of chronic uncertainty price is less important. There is a very inelastic demand for credit at present (meaning it is not very sensitive to price). The US has enjoyed low interest rates for some time now with little evidence that credit is responding in the way the bank hopes.

Further, the whole quantitative easing approach is unnecessary to keep long-term rates low anyway. In fact, the central bank can manage the entire term structure of risk-free yields. All it has to do is to promise to purchase unlimited quantities of government bonds at whatever maturity (length of bond) they want to target at some stated yield.

Also if they want to keep specific mortgage rates low they can offer the commercial banks loans at that rate if applied to home lending. There is no financial constraint on them doing this. They do not have to carry huge quantities of bonds on their balance sheets and provide money in return in the hope that the banks might on-lend it.

There was an interesting article in the UK Guardian (November 7, 2010) – The myths swallowed by George Osborne – which laid out the misunderstandings that pervade the current policy debate.

I don’t wholly agree with the way the author presented the five myths but that is a nuanced disagreement. The myths are well stated and the arguments largely correct.

On the topic of debt costs etc, the article said in relation to the UK that:

About 80% of public borrowing is from the domestic market, what economists call the “non-bank public”. To those who buy them – either directly or through things like pension funds – British bonds are an asset on which holders receive a payment totalling £34bn per annum. The remaining 20% is either held by government departments or is owed to foreigners. Most public borrowing appears as a liability on the government side of the ledger, but as an asset on the ledger of domestic bondholders.

That should never be forgotten. While spending equals income the causality is bi-directional. That is, increased spending leads to higher national income but higher national income supports higher spending.

In the context of quantitative easing, the claim is that by lowering interest rates and the costs of borrowing, credit demand should rise. There is some truth in that. But there are also negative impacts and the net result is far from certain and probably inconsequential for aggregate demand.

The point is that when there are less government bonds in circulation there is less income being received by the non-government sector. Less income means less spending.

While I outlined the nature of quantitative easing in this blog – Quantitative easing 101 – let’s restate it in dot point form.

What does quantitative easing do?

- Government bonds held by the non-government sector are a liability of the government and a source of wealth and income to the holders.

- Such assets have a “duration” associated with the maturity date on the assets – so 10-year, 15-year etc.

- Bank reserves are also a liability of government and have instant maturity (being cash).

- Quantitative easing increases demand in the markets for government bonds and thus reduces their yield. So in thse sense the term structure of interest rates (the mapping of interest rates by maturity) is changed – the yield curve flattens as the longer maturity rates are reduced.

- The purchases are paid for by increasing bank reserves so quantitative easing merely alters the “duration” of the outstanding government liabilities and it is that impact which changes the yield curve.

- It adds nothing directly to aggregate demand (spending) but relies on an assumption that the interest channel (lower rates encourage increased demand for credit) is strong. The evidence suggests that this mechanism is weak.

Which then brings us back to the G20 showdown over US quantitative easing. What could that possibly be about?

Apparently, the ventriloquist’s doll (Merkel) is:

… set to clash with US president Barack Obama at the G20 summit in Seoul this week over the latest programme of quantative easing designed to boost the ailing US economy. President Barack Obama can expect a rough ride at the G20 summit in South Korea this week after China and Germany denounced proposals by the Federal Reserve to flood the US economy with cheap money.

The inflation-obsessed Germans are claiming that the quantitative easing will be inflationary. The Chinese think it will undermine exchange rates (as if they allowed the market to work anyway!).

Please read the following blog – Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion about why it will not be inflationary. Those who think that it will be are still lost in the dark and erroneous world of a money multiplier tacked on to the arcane and plain-wrong Quantity Theory of Money. These two mainstream theoretical shibboleths are without application in the fiat currency system but still dominate policy discussions.

The nations attacking the US plan also think that:

… investors will turn away from the US and pour money into their own economies in search of higher returns. To invest in a country means buying its currency, which raises its value. Brazil’s currency has already rocketed while China, which has pegged the yuan to the dollar, will need to spend more of its trade surplus on artificial measures to keep the currency and the declining dollar aligned.

This obsession with exchange rates. If it is not the claim that deficits will drive the exchange rate down into collapse it is the other that low interest rates elsewhere will push exchange rates up and undermine the export sector. If net exports decline then there is simply more room for domestic spending to take up the capacity.

Indeed, continually running net export surpluses while there are slums and poverty in your neighbourhoods (Brazil and China) makes no policy sense at all. If the governments of these nations are worried about the speculative nature of the “investments” that might be attracted by the rising interest rate spread then they can: (a) reduce interest rates themselves; and (b) direct the “investments” into socially productive activities and bar financial speculation.

After all the national government ultimately can determine what happens to foreign capital investment within its borders.

Note I am not providing a defence here for the US Federal Reserve Bank’s decision. I am just suggesting that the rest of the world also doesn’t understand how this all works.

Quantitative easing does not magically increase liquidity to the rest of the world. Banks do not need the extra reserves to lend. So if there are a host of investment opportunities available investors can already get the funds necessary.

The UK Guardian article then said that:

With Washington paralysed by political infighting and dependent on Bernanke to boost the economy, China, Germany, Brazil and Canada are expected to use the Seoul summit to restate the Toronto deficit reduction plans.

So you see the inherent madness in all of this. Day after day these simple errors are propounded.

First, the US political system has failed and this failure manifests in the dependence the country now has “on Bernanke to boost the economy”. Monetary policy cannot boost the economy in the way the mainstream economists (including Bernanke) think.

Second, the foreign nations then freak out thinking that there is about to be a flood of US dollars into their economy. The US dollars never leave the US banking system. But as noted above the quantitative easing does not provide extra capacity to the banks to lend or for credit-worthy borrowers to borrow. Rates are a bit lower that is all.

Third, despite the largest economy wallowing in a major deficiency of aggregate demand (see output gap graph above) the foreign nations then want to reassert their past calls for less spending (deficit reduction). Spending equals income. Lower deficits now will reduce economic growth. There are not a host of Ricardian consumers and firms just waiting to spend up big as they perceive their “future tax burdens” will be reduced by the austerity packages. That is a major myth.

The UK Guardian’s article on myths says of Myth 2 – The taxpayer pays:

… A somewhat more sophisticated argument used mainly by “financial economists” (the sort who advise Osborne) is that when government debt-financed spending rises, the public cuts its consumption by an equal amount in the expectation that future taxes will rise. This is what economists call the “Ricardian equivalence” hypothesis, first proposed by David Ricardo in the early 19th century and popularised by Robert Barro and other members of the “rational expectations” school of economics which enjoyed brief credibility in the 1970s. Bluntly, there is little empirical support for this hypothesis … The same is true of the oxymoron “expansionary fiscal contraction”; the IMF’s World Economic Outlook (October 2010) could find only two episodes out of 15 of advanced economies expanding as deficits were cut.

Please read my blogs – Pushing the fantasy barrow and Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

The real problem

I thought Paul Krugman’s Op Ed on October 31, 2010 – Mugged by the Moralizers – was fairly apposite in the context of the previous discussion.

After pointing out that the current political sentiment is that “debt is evil, debtors must pay for their sins, and from now on we all must live within our means”, Krugman correctly notes:

And that kind of moralizing is the reason we’re mired in a seemingly endless slump.

He pointed out that the private sector had prior to the crisis been on a credit binge – “unsustainable borrowing” as “Real estate speculation ran wild” (all over the World). Further, this “borrowing made the world as a whole neither richer nor poorer: one person’s debt is another person’s asset. But it made the world vulnerable”.

He doesn’t add that it was also at a time that governments were biasing fiscal policy towards surplus and leaving the credit binge to drive growth. Whenever we consider the actions of one sector (private domestic in this case) we have to also reflect on what the other sectors were doing behaviourally and by way of reaction.

That is because the sectors (government and non-government, the latter composed of the external and private domestic sectors) are intrinsically related through the national accounts. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) emphasises that a government surplus has to be a non-government deficit. The non-government deficit is clearly spread across the two composite sub-sectors.

Further, for a nation running an external deficit (which is providing foreign savings to the domestic economy), the private sector can only save overall (and reduce its stocks of debt) if the government sector runs a deficit. To deny that or to overlook that is equivalent to denying gravity.

So if we identify that the main problem at present is the overhang of private debt and large net importing economies are not about to transform themselves into net exporters (despite Obama’s claim that the US will double its exports in five years) then an intelligent person has to support on-going deficits of sufficient size to support growth or else they have to admit they support recession and ultimately, stagnation.

Its your job at stake!

Krugman notes this when he writes:

The key thing to bear in mind is that for the world as a whole, spending equals income. If one group of people – those with excessive debts – is forced to cut spending to pay down its debts, one of two things must happen: either someone else must spend more, or world income will fall.

This is such a simple story yet in all the public debate now it is getting lost amidst a series of myths about insolvency, intergenerational debt burdens, hyperinflation, and that is before we get to discussing debt slavery and … socialism morphing into communism and … the final battle for freedom and liberty and the American way.

The American way – at least as far as I understand the rhetoric as an outsider – has always been about opportunity (unless your non-white) and prosperity (unless you are poor, disadvantaged, a minority etc). But lets just summarise it as prosperity given that the nation has achieved very high per capita national income rates.

Well what the liberty mavens cannot seem to understand is that defying this simple story about “spending equals income” and pressuring politicians to work against it, they are actually undermining the American way as defined and presumably impinging on the liberty of an increasing proportion of the US population.

A person who is involuntarily unemployed because there is not enough spending to generate enough national income to support enough jobs is not free! More and more people will lose their liberty in this way if the new government composition follows through on their crazy plans to cut net public spending.

Krugman notes that even the “parts of the private sector not burdened by high levels of debt see little reason to increase spending”. There are two elements to this point.

First, firms who have cash at present have little incentive to invest it in productive capacity expansion because they are so uncertain about future sales. They are able to sell what they produce at present and are therefore satisfied. This is an essential insight of Keynes and others in that tradition which MMT continues.

The current state of affairs – with appallingly high unemployment and low activity levels – can be considered an equilibrium in the sense that there are no dynamics present that will change the situation. Firms are producing and hiring at levels that are consistent with their sales. The unemployed clearly desire higher consumption and would buy more goods and services if they were working but that latent demand is “notional” and not effective (backed by cash). The market fails to receive any signal from the unemployed and so firms cannot respond with higher production.

This distinction between notional and effective demand was at the heart of the “Keynes and Classics” debate during the Great Depression, which pitted the UK Treasury view in the 1930s with the emerging views that became identified with Keynes but were also developed by several others (Kalecki, Marx etc).

A major flaw in the mainstream reasoning in the 1930s (and still today) surrounds the so-called “Say’s law” which claims that “supply creates its own demand”. Say’s law denies there can ever be over-production and unemployment. If consumers decide to save more then the firms react to this and produce more investment goods to absorb the saving. There is total fluidity of resources between sectors and workers are simply shifted from making iPods to making investment goods.

Keynes showed that when people save – they do not spend. They give no signal to firms about when they will spend in the future and what they will buy then. So there is a market failure. Firms react to the rising inventories and cut back output – unable to deal with the uncertainty.

The break with neoclassical thinking came with the failure of markets to resolve the persistently high unemployment during the 1930s. The debate in the ensuing years were largely about the existence of involuntary unemployment. The 1930s experience suggested that Say’s Law, which was the macroeconomic component and closure of the neoclassical system based on the optimising behaviour of individuals, did not hold.

The neoclassical economists of the day who were opposed to Keynesian thinking continued to assert that unemployment was voluntary and optimal but that some factors not previously included in the model prevented Say’s Law from working. These factors included the imposition of minimum wages by government legislation. Keynes, following Marx and Kalecki, adopted the distinctly anti-orthodox approach and refuted the basis of Say’s Law entirely.

The theoretical push to reassert Say’s Law by neoclassical economists was severely dented by the work of Clower (1965) and Axel Leijonhufvud (1968). They demonstrated, in different ways, how neoclassical models of optimising behaviour were flawed when applied to macroeconomic issues like mass unemployment.

Clower (1965) showed that an excess supply in the labour market (unemployment) was not usually accompanied by an excess demand elsewhere in the economy, especially in the product market. Excess demands are expressed in money terms. How could an unemployed worker (who had notional or latent product demands) signal to an employer (a seller in the product market) their demand intentions?

Leijonhufvud (1968) added the idea that in disequlibrium price adjustment is sluggish relative to quantity adjustment. Leijonhufvud interpreted Keynes’s concept of equilibrium as being actually better considered to be a persistent disequilibrium. Accordingly, involuntary unemployment arises because there id no way that the unemployed workers can signal that they would buy more goods and services if they were employed.

Any particular firm cannot assume their revenue will rise if they put a worker on even though revenue in general will clearly rise (because there will be higher incomes and higher demand). The market signalling process thus breaks down and the economy stagnates.

Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

So a theory that was categorically reduced to having zero validity in a previous time has remained alive in the conservative economics departments and is once again being used to justify the ideological policy positions. How many government officials who are designing these austerity programs are familiar with the “Keynes and Classics” debate and the subsequent contributions of Robert Clower (1965) and Axel Leijonhufvud (1968), for example? Not many!

How many of Krugman’s debt moralists have any idea that these debates have been traversed in detail before and the current conservative position has been empirically refuted over and over again.

Remember – spending equals income.

And further, if government spending provides more buoyant times via increased sales for firms then they have an incentive to invest again. And … if consumers are not in fear of their jobs then they also have an incentive to spend more or enjoy the increased capacity to reduce their indebtedness.

Krugman clearly knows that spending equals income:

So what should we be doing? First, governments should be spending while the private sector won’t, so that debtors can pay down their debts without perpetuating a global slump. Second, governments should be promoting widespread debt relief: reducing obligations to levels the debtors can handle is the fastest way to eliminate that debt overhang.

Again, this is so obvious that a young child would understand it.

The problem is as Krugman points out that “the moralizers … denounce deficit spending, declaring that you can’t solve debt problems with more debt. They denounce debt relief, calling it a reward for the undeserving”.

Thus we have a case of religious zealotry overwhelming common sense and logic. The religious bullies (the debt moralisers) are indignant if challenged (“they fly into a rage”); invoke ridiculous non sequiturs when cornered (“they call you a socialist”); and think that forcing some over-indebted soul into bankruptcy is good for the economy.

Krugman says:

So the moralizers are winning. More and more voters, both here and in Europe, are convinced that what we need is not more stimulus but more punishment. Governments must tighten their belts; debtors must pay what they owe. The irony is that in their determination to punish the undeserving, voters are punishing themselves: by rejecting fiscal stimulus and debt relief, they’re perpetuating high unemployment. They are, in effect, cutting off their own jobs to spite their neighbors.

Conclusion

Our history has been dominated by the religious purges of innocent communities etc. Religious intolerance starts wars and enslaves nations. It is once again abroad in the form of deficit terrorism. It has contorted the entire policy spectrum and led to destructive political changes (for example, the election of the Tories in the UK and the recent mid-term outcomes in the US).

My own profession should hang its head in shame for being instruments of this religious persecution of the disadvantaged.

That is enough for today!

There is a lot of talk about the Fed’s Quantitative Easing programme and one of the lines the Fed is issuing seems to be using is that ‘asset prices will be higher than they otherwise would have been’.

However haven’t the commentators got this the wrong way up. It seems to me that the needless issuing of bonds by the government and the extraordinary amount of currency they inject as interest on them are actually holding down asset prices lower than they otherwise would have been if those bonds simply didn’t exist.

Wouldn’t it be rational, and perhaps even an easy sell, to point out that if the government stopped issuing bonds not only would the deficit go down but asset prices would probably rise a bit in response. Surely the capital gains junkies in the finance sector would go for that?

I’m trying to understand an operational aspect of the bond purchases. I don’t properly understand how bonds are valued so I’d like some help to get this correct.

If a hypothetical 20 year bond was sold some time ago with a face value of $100 and a coupon of 10% paying $10 per anum.

It is now purchased via QE at a market rate of $100 + X. Assume X is $100. There is now a $200 cash deposit earning interest at the nominal overnight rate, which say for the sake of argument is 5%. The original bond holder would still recieve a return of $10 per anum.

If the original owner of the 20 year bond is happy with the annual return on the cash deposit. Why would he want to do anything with it other than leave it as a deposit.

If the original owner was getting a worse deal. I can see why he might be tempted to look elsewhere. I’m assuming almost all the QE bonds are purchased at a price higher than the par value of the bonds. Maybe this could cause asset inflation, but I don’t see how or why.

I would also add that just like today, there was a big debate in the 1930s over the use of higher interest rates to check unsustainable bubbles. Many in Keynes’ day argued that during the 1920s interest rates were kept too low, and facilitated the unsustainable bubbles in property and stock prices which caused the Great Depression. Keynes argued instead for lower rates, saying that “the remedy for the boom is not a higher rate of interest but a lower rate of interest! For that may enable the so-called boom to last. The right remedy for the [business] cycle is not to be found in abolishing booms and thus keeping us permanently in a semi-slump; but in abolishing slumps and thus keeping us permanently in a quasi-boom.”

This is the problem I have with the hysteria over QE. Prof. Mitchell argues that monetary policy is ineffective, just as Keynes said that “there is a force in the argument that a high rate of interest is much more effective against a boom than a low rate of interest against a slump.” But this does not mean that higher rates are better, and the critics of QE fail to grasp this.

Does Bernanke read newspapers, a short while ago we could read in NYT:

Companies Borrow at Low Rates, but Don’t Spend

As many households and small businesses are being turned away by bank loan officers, large corporations are borrowing vast sums of money for next to nothing – simply because they can.

…

Companies like Microsoft are raising billions of dollars by issuing bonds at ultra-low interest rates, but few of them are actually spending the money on new factories, equipment or jobs. Instead, they are stockpiling the cash

…

The Fed’s low rates have in fact hurt many Americans, especially retirees whose incomes from savings have fallen substantially. Big companies like Johnson & Johnson, PepsiCo and I.B.M. seem to have been among the major beneficiaries.

…

Corporations now sit atop a combined $1.6 trillion of cash, a figure equal to slightly more than 6 percent of their total assets. In the first quarter of this year it was 6.2 percent of assets, the highest level since 1964

…

In the case of Microsoft’s bond offering, … If Microsoft had needed cash, it could have pulled some from its operations abroad, but “borrowing new money on the debt markets is now cheaper than bringing its own money back from overseas,“

Bill, questions pl; You said that “although it won’t do any harm”, how is that so? The Open Market Operation is and has been occurring for some time with the funds going directly into the stocks and commodities. With commodities on the rise, the US $ on the wane, the inflationary effects might not be felt now but in 6 plus months time.

The entire process is not going to benefit anyone as you pointed out and will hurt those who need it the most. The Fed buys the worst UST’s, the Primary Dealers then pump the proceeds into the stock market, commodities and front run the next buy back. In a normal QE process, you can see it working but in the present settings, the market is so distorted as to be ineffective, the long term inflationary effect is brewing in the hunt for tomorrows profits. This is not about excess money sloshing around the system potentially causing inflation, this is money used to purchase worthless asset backed UST’s then pumped into the stock and commodities market which will eventually affect producer price inputs.

Andrew, the only thing I would say here is that the overnight rate right now is 0 percent, which is why people assume that the marginal bond-holder taken out by QE will be forced to chase a higher yield by investing the proceeds in riskier asset classes such as stocks, commodities, etc.

Andrew

Two points here:

1. If today you are a private buyer using your cash to buy the ‘cash like bond’ *from the government*, then the government has your cash for zero sum. But if you sell this bond to the central bank for created cash you have cash *and* the government has cash. All the ‘government’ had to do was print up a bond and the money. The government is then spending created money which given the same amount of land and assets will at least support depressed prices.

2. When the bond is bought from the government via auction it is usually sold at a discount to the face value to reflect the true market rate of interest. So the bond has a true yield coming from the discounted purchase price and the coupon interest rate.

Bonds with the same coupon rate are then bought and sold at different prices relative to the face value to create the actual yield of that bond for the buyer as his own investment.

When the central bank buys the bond it only has to pay a calculated yield amount slightly lower than what anybody else is prepared to pay for it which can be considerably lower than the face value amount. That sounds wrong but for example it pays 950 for a 3% coupon bond with face value of 1000, which pays 30 dollars per year interest. The yield for the central bank is 30/950 * 100/1 = 3.157%

If you just bought a bond from the government you would not have lost 50

This is so because you were reluctant to buy the bond from the government and you put in a bid of 940 for a yield to you of 30/940 * 100/1 = 3.191%

The market was anticipating at least 500 Bn in QE2 for months. Almost certainly there was a leakage of information. The fed is not supposed to surprise anyone.

Isn’t most of the QE2 effect baked into the markets already. Buy on the rumour sell on the news. Traders are running out of asset classes to play with, they could try to crank stocks/commodities up and sell USD every round of QE. But how many more fools are left? By years end maybe they will buying USD and selling stocks/commodities.

After a stock/commodity sell off of 20% in spring they will start working on the trading strategy for QE3. The economy certainly won’t be improving much. The suprise would be a strengthening of the USD, that will leave a lot of inflationists scratching their heads.

Prof. Mitchell, I would like to alert you to a programme airing this week in Britain which I think you will be interested in, entitled “Britain’s Trillion Pound Horror Story”. Just from seeing the trailer currently airing I can tell it is going to be a clusterfuck of irrational nonsense about Britain’s national debt and the terrible burden we are apparently leaving our children.

It airs on Thursday night and is, incidentally, made and hosted by Martin Durkin, the moron who made the infamous “Great Global Warming Swindle” documentary from a few years ago. It would appear he knows as much about economics as he does about climate change.

Maybe Obama hasen’t made much progress for the US citizens, but do you really think changing Government will bring economic stability and jobs for the unemployed?

Andrew,

Thanks, I’m understanding point 2 quite clearly.

Point 1 has flown over my head. I’m impervious to the idea of Government keeping a *cash back* for themselves. Sounds like a waste of time to me. If I could credit the milkmans account without debiting my own bank account, I wouldn’t see the need to have any cash in my bank account.

Andrew Wilkins

In point 1, the government spends the money without having to ‘deflate’ the economy with taxes or borrowings.

So Bernanke say that buying treasuries … “eased financial conditions in the past and, so far, looks to be effective again.” Is it not becoming clearer by the day that it wasn’t the bond purchases at all? Said in another way, it wasn’t the “addition” of reserves at all. Modern central banks, unlike the textbook description, engage open mouth open operation. They don’t inject gazillions of reserves and jam the interest rate (Fed Funds) lower in a fight to the death with the market. Far from it. The market does what is required without a heck of a lot of effort from the Fed, other than the announcement of lower interest rates. So the reaction BB speaks of is the demand elasticity of interest rates (the responsiveness of the punters to cheaper cost of funds), that’s it. When there is demand to incur extra debt – ie. when jobs are plentiful, and when asset prices are not being poleaxed, as just two examples – lowering rates helps, of course. When these conditions do not exist (like now), neither does any type of elasticity of demand for debt exist. This is magnified by not only the “customer appraisal” reason for bank hesitancy to lend noted above by Bill, but by the fact that banks aren’t altogether sure about the assets they’re lending against.

And by the way, those models of consumer and business behaviour in response to interest rates don’t work down at zero, for precisely the reason rates are at zero – debt overhang and a collapsed economy Trying to apply an old model of indeterminate value in the first place to the current situation is, quite frankly, just a suck ‘n see approach. It’s a bit like saying the “wealth effect” from property is “x” (9c in the dollar from memory according to Greenspan??), and whether or not it’s actually right, it was constructed within the narrow context of forever appreciating prices, not a seething bear market.

Andrew Wilkins (Monday, November 8, 2010 at 19:27) – QE bonds are priced at a market rate, not a premium. The market may have rallied in the interim, or it may not have, it doesn’t matter either way. Corporate buybacks have sweeteners generally, but not government bonds related to QE. The point is, government bond holders can sell (or could have sold) anytime they like……the day before QE starts, the day after, between now and June, before it was even announced, whenever. Bondholders hold bonds for the risk characteristics they provide, usually safety. I don’t think it makes sense to say that a bondholder will retain a position through the ebb & flow of market rates for a period of time, and then feel some compulsion to sell to the Fed so they can get long sugar.

Unfortunately, I think that most of the people I know will believe Glen Beck about economics before they will Paul Krugman. And that is not a joke.

Andrew,

Now I get what you mean by point 2. From an MMT perspective we think of Government Borrowing as an unnecessary artifact. Bill has hundreds of references in his blogs that will explain it better than I.

QE purchase of bonds is not causing consumer price inflation. It does not increase the purchasing power of consumers. In fact it may have a deflationary element. Many retirees are dependent on bond yields. Now maybe they cannot get an adequate yield. The cost of insurance for riskier higher yield products may negate any gains. The fresh QE cash is competing in the asset market for the same finite pool of economic rent so there is no net gain in aggregate demand. There may be associated asset inflation, but some of us suspect this is mainly driven by the the psychology of asset markets. Short term leveraged trading positions that can reverse at any moment.

If you suspect bond issuance is deflationary and Government bond purchases are inflationary. Try increasing income tax in proportion to the 600 billion of bond purchases. You might get a shock as 600 billion of aggregate demand is sucked out of the system.

Conversely, bond issuance is not necessarily deflationary. Replace the term “Government borrowing” with the thought that Bond issuance competes for savings in the private sector. These savers are looking for the lowest risk of return. Should there be no option for a Government contracted fixed return of a certain duration, the savers will look for the next lowest risk option. These savers will not suddenly turn around and buy a load of jet skis.

Without Bond issuance, savers would be limited to the floating rate on offer by Government or they can chase after the finite pool of rental yield in the private sector. If you stick around a bit more you will learn how Government spending deficits provide the private sector with an opportunity to net save. These savings are not inherently inflationary, people who save are trying hard not to spend the money.

I find it a bit nutty to think the Government must appropriate private savings at arbitrary contracted rates, out of some unproven notion balanced budgets are necessary over the business cycle. If they had this ridiculous notion since Government deficit spending day 1, they would be trying to issue contracts for every dollar in the private sector. (That is, every dollar representing private net assets)

Andrew Wilkins

>>From an MMT perspective we think of Government Borrowing as an unnecessary artifact

Are you sure you are not getting confused by the terms ‘accounting fiction’ used to describe the relationship between central banks and treasury by Mosler?

According to Mosler, the government spends assets into the economy and then uses bonds as part of monetary policy to drain the assets accumulating in the private sector that are not drained by taxation.

http://pragcap.com/mmt-101

>>I find it a bit nutty to think the Government must appropriate private savings at arbitrary contracted rates, out of some unproven notion balanced budgets are necessary over the business cycle.

So according to him buying bonds is necessary when the government spends more than it earns from the economy and this results in inflation.

“Therefore, the key to understanding Modern Monetary Theory is this vertical-horizontal relationship. When one understands this, then Abba Lerner’s principles of functional finance become obvious. (1) Currency issuance through government disbursement is used to increase non-government net financial assets, and taxation withdraws net financial assets from non-government. (2) Debt issuance by the Treasury is a monetary operation for draining reserves to permit the Central Bank to hit its target rate

Of course the Fed Chairman must continue to solemnly suggest that they wield powerful tools to modulate the economy. To admit that they can do little to effectively help the economy (when help is REALLY needed) would be to admit that they could be dispensed with.

Bill,

there’s one point in this blog posting which undermines much of the spot-on observations;

“The religious bullies … think think that forcing some over-indebted soul into bankruptcy is good for the economy.”

1) it’s obvious they don’t think at all, at least not deeply 🙂

2) that aside, what’s the harm in bankruptcy? if someone has perpetrated a fraud on their community, by over-promising their ability to execute, it’s rational to execute an appropriate return of assets to creditors, ASAP;

(Goldman Sachs, Citibank, BOA, AIG … etc, come to mind)

What I presume you’re really proposing to eliminate is excessive punishment of people for projects failing, to the point of removing productive capacity from the community. There is a critical difference – that depends on the terms of individual bankruptcy cases, not bankruptcy itself.

GLH: “Unfortunately, I think that most of the people I know will believe Glen Beck about economics before they will Paul Krugman. And that is not a joke.”

—————–

Nope. No joke. A big chunk of Americans get their economics education from Glenn Beck.

I’m quite relieved to hear from Professor Mitchell that QE won’t do any harm. Beck was starting to affect my mind too. You watch him every day, and he starts speaking to your inner Demon. I was starting to feel like the end was near. And then I read today that Ron Paul said that the QE is going to destroy everything. I started to despair.

And then I come here to read the soothing words. Despair not. It won’t make us better, but it won’t kill us either.

Re “Brazil’s currency has already rocketed while China, which has pegged the yuan to the dollar, will need to spend more of its trade surplus on artificial measures to keep the currency and the declining dollar aligned.”

By the way, through what mechanism does China peg its currency to the dollar? Do they have to sell more and more yuan when the dollar falls?

What I don’t understand is why Paul Krugman upholds the accounting identities approach (spending = income) and yet still claims that government spending has to be backed by debt or taxes dollar-for-dollar – since this guarantees that the whole world economy is net zero (or negative, taking interest charges into account) sum and therefore real economic growth without deflation becomes impossible. Or is there a subtlety I’ve missed here?

roger erickson: “what’s the harm in bankruptcy? if someone has perpetrated a fraud on their community, by over-promising their ability to execute, it’s rational to execute an appropriate return of assets to creditors, ASAP;

“(Goldman Sachs, Citibank, BOA, AIG … etc, come to mind)”

As frauds or creditors?

One problem with bankruptcy right now in the U. S. is that it threatens to overwhelm both the legal and economic systems, by being so widespread. Bankruptcy is costly to everybody: the debtor, the creditor, and the society. Instead of Too Big To Fail, isn’t it a case of Too Many To Fail?

Another problem is that of fraud by the lenders. Loans were made with the expectation of default and foreclosure. The fact that this was an industry wide business plan is revealed in the recent changes in bankruptcy law in favor of creditors. The lenders were preparing for widespread bankruptcies. I have said that, even if economists don’t recognize bubbles, con men do. The lenders recognized the housing bubble some years ago.

Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh are “reformed” divorced alcoholics and drug users who never completed an advanced degree beyond high school. The fact that they are mentioned in the same sentence as Paul Krugman is an embarrassment to economists the world over. I do not agree with all of Mr. Krugman’s views (Prof. Mitchell has a better grasp of macroeconomics), but at least he is on the correct path. I would actually like to see a “conservative” dismantle the Beck/Limbaugh duopoly by expounding the MMT perspective through tax cuts (t-party would support it) as Warren has proposed in his platform. Not a perfect solution to the problem, but at least it would frame the debate in tax cuts vs. increased spending and not deficit hysteria/debt mania. The conservatives hate Krugman and anyone who would support federal spending as a solution to the current economic stagnation, but they will ALWAYS get behind tax cuts. Once they stop attacking the deficit/debt as the root of all evil, then at least there would be a CHANCE for prosperity and perhaps a debate based on reason and logic vs. Beck & Limbaugh.

Not that we have democracy in its strict terms of meaning. First of all, our national decision-makers are not threatened with unemmployment. (Plenty of jobs out there for them even if they are no longer office.) Furthermore, Washington D.C. is the brothel of the United States for all intensive purposes. (This is the premier place to go to, if you want to buy political influence, after all!) As for the peons … *ahem* … the voters, all they care about is for someone to provide them with emotional swings and results. Unfortunately, they do not want to think about the ‘how’ part of getting results, but only the result. (Perhaps they even seriously believe in making a loaf of bread from nothing!) Also, in the realm of politics, 1 + 1 can be 2, but cn also be some other number. Put all these things together, we end up with a system that promotes careerists who are good at exploitation under the veil of legality and morons who is more concerned about looking good than actually doing something with a vision.

The US healthcare squabble a couple of years ago is a good snapshot. This is fundamentally an economic issue, therefore healthcare economists should have gotten the bulk of airtime. But what happened? On one hand, we were swamped by politicians and pundits screaming about ‘socialism’ and on the other hand, a bunch of elderly who screamed, ‘Get your [government’s] hands off of my Medicare!’ (rather moronic, considering the federal government is the one who provides Medicare!). Notice that sanity is impossible when the debate is dominated by those who are irrational and moronic. Not surprisingly, the same pattern holds true with debates about fiscal policy.

Debit, this is the fault of the media on one hand, and the public on the other. There was a lot of analysis from experts that was available on the Internet, but virtually none of it made the media because it is not entertaining. While the media is at fault for failing to meet their responsibilities, they are just businesses responding to consumer demand, which is for sensationalism and entertainment. The American public deserves what is in store for it.

When the CB buys a bond, the interest income is used to pay CB expenses with the residual passed onto Treasury as seignorage income, which is spent. The private sector is not “losing” any interest income when the CB buys assets, neither is it gaining interest income should the CB unwind the sale. I keep reading about the “deflationary” effects of CB asset purchases and don’t understand the logic behind this. The government is much more likely to spend the interest income more quickly than the private sector.

More generally, money does not chase assets; it does not even get up and walk over to assets. Money is an asset; what chases assets is a flow of money.

As Keynes said in his letter to Roosevelt

Actually, that letter, as it was written in response to the 1937 contraction, it is appropriate reading for today.

Tom, I feel the same way regarding the American public. After a while, I have gotten sick and tired of blaming our miseries on the mass media. (Not that the mass media is not at fault, as it has been an accomplice; it takes to tango together.)

As for the Internet: I have found good articles and recorded lectures on healthcare economy. The funny thing is, they are very easy to find! Of course, these things are not money-makers; the hell has a greater probability of ascending into the heaven than these articles and lectures showing up in the mass media. This reminds me of underutilization of the public library system. (You only need to show an ID and a proof of residence to get a library card … very easy!) There are also classes available for adults either free or small registration fee (depending on the provider). Yet not many adults take advantage of these public resources. So much for ‘individualism’, ‘do-it-yourself’ American cultural mantra! Instead, they would rather like to be spoon-fed, and do not even bother trying something that is 99% ready-to-be-spoon-fed. Instead, they go nuts whenever someone mentions about their sorry state.

As a matter of fact, the US should change its official name. United states of Amnesia? Moronic States of America? Or … more insultingly … United States of Arsewipes?!? (A country’s name ought to reflect its state of being!)

Beyond mere ranting, I am concerned about the decrepit state of American liberals. Even their supposedly ‘liberal’ Democrats are more interested in making themselves appear like ‘Republican-lite’. It will take a miracle for them to wrest initiative from the American conservative and right-wing establishments.

RSJ:

”

When the CB buys a bond, the interest income is used

”

I believe Andrew is worried more about potentially depressed T-bonds yields, as a hoped for result of QE2, rather than the “lost” interest on the extracted from circulation T-bonds.

Obviously, as you said, the interest will be redistributed through the Feds-return to->Treasury->spending chain.

It is less clear what will happen with the yields, but most likely not much.

P.S.

Is Keynes’s a kind of New Testament quotation ? Would von Mises’s qualify as an OT one ?

😉

P.P.S

I am not entirely convinced about the extra cash, as a QE2 byproduct, not having any effect on investment decisions and for example not pushing commodity prices up, the absence of “mathematical relation” notwithstanding.

Money is an asset; what chases assets is a flow of money.

A flow of moneys chases money? ……….. I’m sure you didn’t mean that. 🙂

As some of us have no formal training in economics we often make unintentional mistakes with syntax. For those with a formal economics training and long experience in the field, you will have to try and interpret the intent of our newbie posts. We do try our best.

I think us “non economists” can bring some insight into the thought processes of the general public. I am an engineer by trade, so I think of monetary systems in the same way as hydraulic systems usually. If I ever get some time I’d like to build a model of an economic lawn being watered by a monetary system.

The fed would be a complex system of valves and pumps doing nothing useful to water the garden. The treasury is connected to the mains. If you water the garden too much you get inflation shown by puddles of water, too little and the grass dies. Sell hay abroad for extra fertilizer or garden gnomes. Banks act kind of like hydraulic accumulators pumping water in and sucking water back out.

Dear Andrew Wilkins (at 2010/11/11 at 20:58)

One of the greats A.W. Phillips (of the Phillips curve) invented the MONIAC which was a hydraulic model of the macroeconomy.

You can see a video of the machine working HERE.

There are several still in working order around the World.

best wishes

bill

Nice! ….. very Heath Robinson.

I was thinking of something more cartoony and sim city like. On MMT principles of course.

Saving = Income; so what happened last January when I bought a new 55 inch LG flat panel for my family room? Did I add a bunch of income for South Korea? I’m sure a few dollars leaked out to the local economy, but for the most part I don’t feel like I created much income in my country. Am I wrong?

So if the U.S. runs a large trade deficit, were do all those extra dollars go when they don’t come back to the U.S.? Treasuries, Somlia Pirates, ????? It seems to me it all has to equalise at some point.

So if the U.S. runs a large trade deficit, were do all those extra dollars go when they don’t come back to the U.S.?

Probably eventually go mostly to the oil producers since petroleum is denominated in USD. Then these USD’s return to the US as purchases of tsy’s, assets, and weapons, as well as some RE and goods purchases. But there are also a lot of dollars in foreign banks. They are called Eurodollars. There is also a lot of US currency circulating abroad, mostly $100 bills. It’s the high liquidity favorite of the vast grey and black economies.

thanks Tom, and I did notice I said savings when I meant to say spending = income