I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Foreclosures – problem or not?

The news from the US housing market remains pretty bleak three years after the financial crisis began. Last week, we read that attorneys general from all 50 states were investigating allegations that some major banks inappropriately reviewed mortgage files and/or tendered false foreclosure statements which led to the eviction of thousands of delinquent borrowers from their homes. Apparently, banks and credit suppliers used “robo-signers” to sign false affidavits. The US federal regulators are meeting today (October 20, 2010) to discuss the “foreclosure crisis”. The question is whether this will become a bigger problem and spill over into the real economy and worsen the unemployment crisis. The governments have all the tools and capacity they need to ensure that any financial crisis is totally insulated from the real economy. But their reluctance to show the necessary policy leadership almost ensures that a financial crisis will spread and wreak havoc in the real economy. Their lack of policy action amounts to plain stupidity or malicious contempt for their citizens. Probably both.

The estimates of how bigger an issue the foreclosure crisis will become vary from those who consider it will be the beginnings of another full-blown financial crisis to those who think it is just a beat-up that will merely require some additional documents to be completed and it will be back to business for the banks.

I read an interesting article on it yesterday which suggests the crisis will be big.

The issue however raises interesting questions that are typically not well understood. For example, if I was to ask 100 people if the government could have stopped the financial crisis spreading into the real sectors (output and employment) most people would have denied the government has this capacity.

In fact, the spreading of the crisis into the real sector was a political choice.

It is in this context that I published a paper in 2009 entitled – There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending – you can read the Working Paper version for free (which is fairly close to the final publication).

I also referred to this paper in a recent blog – There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending – still! – and clarified what I meant by the statement.

The statement reflects a basic insight that is derived from Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) which provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how the monetary system actually operates rather than how the mainstream macroeconomics textbooks (and most commentators) pretend it operates.

I noted that some people have claimed that the leading proponents of MMT think that fiscal policy can “bail” an economy out of any problem. Where people get that mis-representation from is anyone’s guess but then I (for one) have been getting verballed all my academic life. I refer you again to the great article by Richard Hofstadter – The paranoid style in American politics – which was published in the November 1964 edition of Harper’s Magazine.

The easiest way to dismiss a theoretical or policy framework that you cannot logically fault but hate is to label it whacky or communist. Either will do the trick and that usually avoids any further need to engage with the ideas. I am used to that after some years in the business.

If someone calls me a communist I take it as sign that they are aggravated by my ideas and haven’t the capacity to refute them in the normal way that science proceeds to determine what is knowledge and what is not.

Anyway, as I noted in last week’s blog, when I say – “There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending” I do not mean the following:

- That fiscal policy can overcome the real losses to a nation’s standard of living that are associated with a major fall in its currency when there is a significant dependency on real imported goods and services.

- That fiscal policy can ensure that debts denominated in foreign-currency (public or private) can be honoured at all times.

What the statement means is that a situation can always be improved if the origin of a crisis is in the private financial markets. If you want to take an extreme situation, the US government has the fiscal capacity to ensure than no person “lost” any nominal wealth (say, in the form of superannuation benefits which are tied to sharemarket performance) as a result of the property collapse.

Now before you start writing in to the blog about the absurdity of that statement think hard about it. What is the basis of the loss – some nominal write-down in share values, property values whatever. Some accounts/ledgers get changed. A sovereign government has the financial capacity to change them back to the pre-crisis value if it wanted to.

I am not advocating that the government insure all private sector risk. I am just making the point – which might seem to be extreme – that the implication of a sovereign government not being revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency is that it could if it wanted to.

Another way of thinking about this is to ask yourself the following questions which bear on why I would not be at all worried about the foreclosure crisis other than to ensure those who commit criminal acts are punished and the disadvantaged persons without work are offered public sector jobs and the chance to rent their houses for some period.

Before I get to the questions, note that in this blog – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism – I outlined a desirable policy initiative to help home-owners who were facing eviction from their homes because they could no longer service their debts.

There are around 26 per cent of US mortgages now in default and the proportion is rising. So there will be a lot of (legal) foreclosures to come yet quite apart from the illegal ones that seem to have been initiated by the corrupt banks.

I suggested the following process which would be within the capacity of a modern monetary government to implement and fund:

- The government should not interfere with repossession processes. A private contract is a private contract.

- But the government should consult with the defaulting private owner to ascertain if they want to keep their house.

- If they do want to keep their homes, the government should purchase the house from the bank that is foreclosing at the fire-sale price.

- The government should then rent the house back to the former owner for some period – say 5 years.

- At the end of this period the former owner would be offered first right of refusal to purchase the house at the current market price.

- The government would also offer the former owner guaranteed employment in a Job Guarantee, to ensure they are able to pay the rent and reconstruct their personal finances.

- This option does not involve any subsidy operating (market rentals paid, repurchase at prevailing market price); no interference into private contracts, and people stay in their homes.

- There is no moral hazard components within the proposal.

Financial crises involve changes in the nominal value of assets and, initially, no real assets are damaged. The crisis in Haiti is an example of a real crisis where tangible assets – houses, productive capital are destroyed.

Ask yourself: Are there any less arms and legs queuing up for work each day when the share market collapses?

Are there any less tractors, trucks, machines, computers etc available to complement the labour resources when there is a financial crisis?

The issue that arises is to consider why a financial crisis becomes a real economic crisis. The reality is that I am worried about the foreclosure crisis should it turn out to be significant because it is clear to me why a financial crisis unnecessarily spills over into a real economic crisis.

Why does it happen? Answer: total failure of macroeconomic policy.

I was thinking about this again today as I recalled a paper I read from the IMF World Economic Outlook last year – From Recession to Recovery: How Soon and How Strong?.

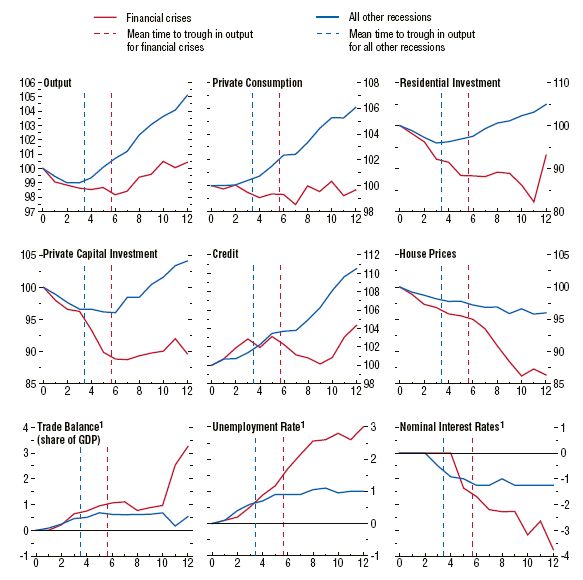

The IMF paper provides the following graph (their Figure 3.8) to show the temporal profile of recessions and recoveries associated with financial crises and other shocks. The median = 100 at t=0 and the peak in output at t=0 and the x-axis is specified as quarters.

The IMF paper then asks:

What are the mechanisms that differentiate recessions and recoveries associated with financial crises? An answer to this question needs to take into account the nature of the expansions that preceded these recessions. Narrative evidence indicates that these episodes have often been associated with credit booms involving overheated goods and labor markets, house price booms, and, frequently, a loss of external competitiveness … Credit booms have frequently followed financial deregulation. Rapid credit growth has typically been associated with shifts in household saving rates and a deterioration of the quality of balance sheets.

However, after a financial crisis strikes, saving rates increase substantially, especially during recessions … Taken together, the behavior of these variables suggests that expansions associated with financial crises may be driven by overly optimistic expectations for growth in income and wealth. The result is overvalued goods, services, and, in particular, asset prices.

Credit booms are the result of poorly implemented financial regulation and lax fiscal policy. The government can always introduce changes to the tax regime to ensure that asset price booms are contained. They can also ensure that financial regulations hinder speculative investment that is not adding productive capacity.

Further, by providing enough social housing, the government can ensure that there are no shortages which might lead to scarcity-price booms. Please read the following blog – Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – for further discussion.

Credit booms are also more likely to occur when the government is running budget surpluses because they squeeze the purchasing power and drain the savings of private households and firms. The only way an economy can grow under the dragging weight of a budget surplus is to have strong net exports (usually not present) and/or growth in credit-motivated private spending (consumption and investment).

If you examine history you will see that when governments run surpluses inevitably a downturn follows a short time after where net exports are negative).

The IMF paper also notes that the recovery phase after a financial crisis appears to be different to other recessions. They highlight the fact that “the weakness in private demand tends to persist in upswings that follow recessions associated with financial crises”.

Thus, output growth is sluggish, and the unemployment rate continues to rise by more than usual. Credit growth is faltering, whereas in other recoveries it is steady and strong. Asset prices are generally weaker; in particular, house prices follow a prolonged decline. On the other hand, although the recovery of domestic private demand from financial crises is weaker than usual, economies hit by financial crises have typically benefited from relatively strong demand in the rest of the world, which has helped them export their way out of recession.

There are three important points to note here. First, the reason that private demand is persistently sluggish after a financial crisis relates to the balance sheet effects that arise as the asset price bubbles burst. Households remain heavily indebted around the world at present and retain very precarious balance sheets.

Monetary policy has to keep low interest rates otherwise there will be mass bankruptcies among the mortgage holding class given the extent of outstanding indebtedness.

So while it is clear that we should not expect any rapid recovery in private spending it is also clear that the government has the capacity to fill the spending void with expansionary fiscal policy. The fact that the fiscal responses have been muted does not negate the effectiveness of the policy tool. It just tells us that the deficit terrorists have been winning the public debate – fear, it seems, is a more powerful force than logic and understanding.

Second, the financial crisis deepened because it morphed into a real crisis. Many of the so-called toxic or bad loans would have remained “good” loans had the debtors retained their employment. The extent of the sub-prime crisis was amplified because the governments failed to quarantine the real economy from the initial stages of the financial crisis.

Even now, the rising foreclosures are preventable – mostly – by job creation. Which should give you a clue to why the financial crisis became a real crisis.

Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on the concept of a balance sheet recession.

Third, note that if a nation can export into a growing world market the negative impacts of the sluggish private spending are attenuated and a nation can quicken their recovery. The problem is that the deficit terrorists have created the conditions where this will not be possible this time around.

By politically pressuring governments to implement premature fiscal withdrawals on a more or less coordinated or highly synchronised basis they have damaged export markets.

The latest news from the British Confederation of Industry is that (Source):

The recovery in British manufacturing has stumbled, with factory orders falling at the sharpest rate since April and optimism reaching a 14-month low … Export orders fell at the fastest rate since February …

Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

So the important points are that:

First, there is hardly any prospect of growth in private credit fuelling spending growth early in the recovery phase of a recession driven by a financial crisis. The IMF note that “credit remains essentially flat even up to two years after the end of the recession, a pattern that is significantly different from all other recovery episodes”.

Which then leads me to ask why the central banks think that further quantitative easing will do anything. Bloomberg carried a story yesterday (October 19, 2010) – Quantitative Easing Only Show in Town For Fed.

The UK Guardian also reported today (October 20, 2010) that Mervyn King hints at fresh round of quantitative easing.

The Bloomberg article is written by English economist (former BOE monetary policy committee member) David Blanchflower who these days appears to be on the moderate side of the debate, which just goes to show how far the centre has shifted right!

Blanchflower said:

The Fed is especially concerned about unemployment and the weak housing market. Chairman Ben Bernanke made that clear in his speech last week. It would be a major surprise if the Fed didn’t do more quantitative easing — creating money by enlarging the central bank’s balance sheet with the purchase of securities — at its next meeting. Failing to act now with such high expectations may throw the markets into a tailspin.

The economic models are telling us that we need more stimulus. Lowering interest rates and more fiscal stimulus are out of the question. Quantitative easing remains the only economic show in town given that Congress and President Barack Obama have been cowed into inaction.

So – more stimulus is required. I agree emphatically with that assessment. Even in Australia, where the recession was muted we have a legacy of persistently large pools idle labour (see below).

It is also clear that monetary policy (interest rates) are as low as they can go.

Blanchflower clearly recognises that the political constraints are up against further use of fiscal policy. There is no financial reason why governments should not expand their net spending and create jobs which will go a long way to easing the impacts of flat private credit demand.

The deficit terrorists – backed by the big right-wing media barons – have cost the world billions of dollars in lost income and forced misery on millions of people who are now enduring long-term unemployment and poverty. They should be tried – one by one – for crimes against humanity.

Which leaves quantitative easing …

We are still relying on the policy regimes – a dogmatic reliance on monetary policy and an eschewing of fiscal policy – which was the policy bias that helped get us into this mess in the first place.

With fiscal austerity now also beginning to undermine aggregate demand, the policy response of many governments is now totally concentrated on quantitative easing (and low interest rates).

We should be absolutely clear on what the BOE (and the Federal Reserve) is doing. Essentially, they are buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (central bank reserve balances). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates.

So the hope is that by holding down longer rates and reducing the cost of investment funds, the policy intervention will stimulate aggregate demand. But there is another side of the coin. The lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who may then reduce consumption (demand) accordingly. How these opposing effects balance out is unclear. The central banks certainly don’t know! Overall, this uncertainty points to the problems involved in using monetary policy to stimulate (or contract) the economy. It is a blunt policy instrument with ambiguous impacts.

So does quantitative easing work? Answer: Not in any significant way.

The mainstream belief is that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment.

It is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

This is a completely incorrect depiction of how banks operate. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

The major formal constraints on bank lending (other than a stream of credit worthy customers) are expressed in the capital adequacy requirements set by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) which is the central bank to the central bankers. They relate to asset quality and required capital that the banks must hold. These requirements manifest in the lending rates that the banks charge customers. Bank lending is never constrained by lack of reserves.

Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Here is a basic question the proponents of quantitative easing need to answer: If economies are now slowing in more or less direct response to the withdrawal of the fiscal support and with short- and long-rates remaining low (and falling at the long end) but still credit demand is weak why would we think more of the same monetary response will suddenly change things for the better?

There is still a belief that monetary policy should be the primary counter-stabilisation aggregate policy tool. The attacks on the use of fiscal policy despite all the evidence supporting its effectiveness are consistent with this view. There is still the naive belief that monetary policy will help.

The low interest rates were never going to stimulate strong rebounds in investment spending while the economic prospects remain so gloomy. Business firms will only invest if they think they can realise profits from the extra production. It doesn’t matter how cheap the loans are – if the output cannot be sold it is not worth producing.

The idea that the private sector would sink into an recession impasse where there was no incentive to expand spending despite the massive latent demand potential embodied in the unemployed should they regain employment was the centrepiece of Keynes’ idea of an under full employment equilibrium. It was this idea that provided the rationale for an exogenous (external to the impasse) injection of public spending.

Such spending would kick start the production process and engender confidence among firms that demand growth might be more robust. The extra jobs that the public stimulus supports also provides incomes to the previously unemployed who then spend more and via the multiplier the expansion broadens across the economy.

It is this simple logic that the fiscal austerity camp have somehow missed.

So the results that the IMF have found – the different behaviour of economies after a financial crisis relative to other shocks – are really just telling us the obvious.

When private demand slumps and credit demand remains flat, there is a greater need for expansionary fiscal intervention than otherwise. Fiddling with rates at the longer segments on the yield curve (quantitative easing) will do very little to stimulate aggregate demand.

The reason why financial crises morph into real economic crises is because governments have been bullied into adopting overly-conservative fiscal responses.

It remains true thought that if they adopted a more appropriate expansionary response, then there is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending!

As an aside I also liked the reference that Blanchflower made to central bank independence. He said:

The new government under Prime Minister David Cameron has made it clear it wants to coordinate monetary and fiscal policy. So Chancellor George Osborne’s intervention at the International Monetary Fund meetings, saying he wanted more monetary easing, came as no surprise before he announces a program of massive fiscal tightening. This raises the question of who is setting central-bank policy. Will Osborne decide the scale, timing and type of assets to be bought? If so, we don’t need an MPC.

In any case, Osborne does have the power to change any decision he doesn’t like if he considers it in the national interest under the Bank of England Act - such as raising interest rates. So the MPC is now under the chancellor’s thumb, which may be a resigning matter for some. I certainly would not have taken to being told what to do.

When I was a member of the MPC, we first asked the Treasury for permission to do so as we needed to insulate the Bank’s balance sheet. Chancellor Alistair Darling then wrote back and agreed to QE up to a fixed amount, leaving the details of the speed, scale and type of purchases up to the MPC. We asked him rather than the reverse.

So all you neo-liberals out there who claim that central banks have independence and that allows them to pursue their policy decisions without political interference better think again. Central banks are part of the consolidated government sector and if they don’t do as the government wants will quickly find who makes the monetary policy decisions.

Conclusion

So why would I be worried about the foreclosure mess? The reason is obvious. Our governments are unwilling to demonstrate leadership and use fiscal policy to advance public purpose.

They can always ensure that people have jobs and can afford to service their debts and keep other businesses thriving. They can always ensure there is enough public housing to meet demand (unless there is a shortage of real resources). They can always fund hospitals and schools and ensure that the real productive capacity is more fully utilised.

They can thus always largely insulate the real economy from any financial crisis while the central bank can ensure that there are no widespread financial collapses (by nationalising insolvent private banks).

The governments around the world are to blame for allowing the financial crisis to worsen and then create real havoc across the world economies. It was preventable even after the sub-prime crisis started to unwind.

There are still the same number of arms and legs ready to work. The government can always put them to work. The rising unemployment is a political choice – conditioned by years of neo-liberal pressure telling us that unemployment is voluntary and optimising behaviour. Whoever believes that should be rounded up and …

Digression: Australia’s not so fully employed economy

I am pretty tired of hearing journalists and business commentators raving on about how our economy is at full employment.

Here is a snapshot in recent days:

The Australian (October 19, 2010):

By now the budget should be in surplus given the China boom has pushed the terms of trade to a 60-year high and the economy close to full capacity.

The Sydney Morning Herald (October 18, 2010):

But because it comes at a time when we’re already at full employment then, to the extent we’re not adding to our supply of skilled labour via immigration, this will require a reallocation of resources within Australia.

Every day or two this mantra is rehearsed.

Latest facts:

1. Labour underutilisation rate is 12.5 per cent – unemployment plus underemployment.

2. Skilled vacancies fall 0.5 percent in October – Source: DEEWR Vacancy Report

3. A leading index of economic activity – “which indicates the likely pace of economic activity three to nine months into the future – has now dropped for five consecutive months from a peak of 10.5 per cent” – The Age.

I wonder whether these journalists ever talk to anyone who is unemployed or think about the data much.

Listening to:

John Kpiaye – Red, Gold and Blues (1994) – beautiful English/Nigerian guitarist.

That is enough for today!

“The deficit terrorists – backed by the big right-wing media barons – have cost the world billions of dollars in lost income and forced misery on millions of people who are now enduring long-term unemployment and poverty. They should be tried – one by one – for crimes against humanity.”

I’ve thought for many years Murdoch was the most evil man in the world. While he was plotting to take over sky news, I read a comment that described him stroking a white cat …… …… well, it made me laugh.

Then there’s the tweedledum and tweedledee billionaires in the UK. Next up for the guillotine.

Any more contenders?

Could someone explain why QE devalues the currency. I assume that is the reason the US dollar has been falling.

“What is the basis of the loss – some nominal write-down in share values, property values whatever. Some accounts/ledgers get changed. A sovereign government has the financial capacity to change them back to the pre-crisis value if it wanted to.”

An interesting concept.

If all countries ran MMT then this would probably work however lets say only Australia did (all things equal overseas). If net private wealth fell 25% due to the GFC (stocks, property etc as you mentioned) and the Aust Govt made each individual whole again (in AUDs obviously), the AUD would surely be hammered.

In this scenario how could the following be fulfilled? (I’m thinking repayment of non-AUD debt)

“That fiscal policy can ensure that debts denominated in foreign-currency (public or private) can be honoured at all times”.

In another scenario, if every country in the world ran MMT and one country made all GFC losses whole, yet others made say only 1/5th whole, wouldn’t the same situation occur as above?

‘I am not advocating that the government insure all private sector risk. I am just making the point – which might seem to be extreme – that the implication of a sovereign government not being revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency is that it could if it wanted to.’

Sorry Ray, I think you forgot to include the subsequent paragraph in your post

“The deficit terrorists – backed by the big right-wing media barons – have cost the world billions of dollars in lost income and forced misery on millions of people who are now enduring long-term unemployment and poverty. They should be tried – one by one – for crimes against humanity.”

Seconded by Andrew. Thirded by me most enthusiastically!

GLH, QE results in the wealthy having an excess supply of cash. Holders of that cash will try to invest in other assets, which helps explain why stock markets have done quite well over the last year or two despite the recession. Plus that cash will seek out investment opportunities in other countries, which tends to devalue the currency of the country concerned.

Plus QE is supposed to boost demand within the country concerned, which tends to draw in imports and depress the relevant currency. But I think this is a weak effect compared to the above “investment” effect. So far as the “demand boosting” effect goes, QE is often described as “pushing on a bit of string”, a description I go along with.

Yves Smith has extensive coverage of folclosures:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/category/real-estate

“The low interest rates were never going to stimulate strong rebounds in investment spending while the economic prospects remain so gloomy. Business firms will only invest if they think they can realise profits from the extra production. It doesn’t matter how cheap the loans are – if the output cannot be sold it is not worth producing.”- To me the key issue is that “investment” in assets is no longer about whether those assets supply a yield of earnings. That rational productive side of investment has been lost under the glut of cheap money. Now “investment” is about harvesting money from being able to out fox the market in handling asset price volatility. QE will push up stock and gold prices because high frequency traders will be provided with cheaper leverage from the banks. The high frequency traders will just be harvesting the “dumb” investors who buy high and sell low.

OFF topic: Just read George Osbornes statement. Wow. I’m speechless. The Brits are really determined to commit economic suicide ASAP.

Could it be that QE, by increasing liquid bank reserves, can contribute to foreign exchange volatility? The banks that are building these liquid balances must hold them in some currency. Is it possible that they are shifting their balances around opportunistically in response to short-term rate changes? I have not heard anyone talk about this possible downside to QE and would welcome comments from Bill or others.

Ray: “In this scenario how could the following be fulfilled? (I’m thinking repayment of non-AUD debt)

“That fiscal policy can ensure that debts denominated in foreign-currency (public or private) can be honoured at all times”.

You’ve got that backwards, Ray. The full quotation:

” I do ***not*** mean the following:

. . .

“That fiscal policy can ensure that debts denominated in foreign-currency (public or private) can be honoured at all times.” (Emphasis mine.)

William,

From what I see happening here in Asia. QE is driving huge sums of money into Asian stock markets, but not for the reasons you suspect. The rumours are all about hedge funds and investment banks speculation. They are front running clients accounts and “buying the rumour” ahead of fortcoming QE2 announcements. All the Asian countries are really worried about it. It is defying the fundamental valuations of the underlying stocks.

No extra money is being “created” by QE. I suspect most of the QE cash is risk averse and stays at home. I strongly believe the sharp currency movements are driven purely by speculative sentiment. Hedge funds and trading desks can be hugely leveraged, but I doubt they are putting up fresh collateral made from QE money.

It is the fear of collapsing economies at home, causing the wealthy to hedge their wealth overseas. QE2 announcements are the market signal to the dumb money, the smart money is already positioned. It’s ironic the markets know QE and austerity budgets won’t work. It’s interesting Bank economists aren’t telling us the conclusions they have obviously arrived at in private.

The Asian countries know from bitter recent experience the hot money will leave as fast as it arrives.

Andrew Wilkins “The Asian countries know from bitter recent experience the hot money will leave as fast as it arrives.”-

-What I don’t understand is why the stock markets are not set up so as to favour “stay the course” money that is actually of some use to the companies. If the companies listed received a payment (of say 5%) whenever a share or theirs was bought or sold at the expense of the buyer and seller- then that would stop all the speculative flitting in and out money from ripping off the valuable “stay the course” money.

-“I suspect most of the QE cash is risk averse and stays at home”-isn’t supplying leverage to day traders on a one day basis a very risk adverse type of lending for the banks. The traders have to stake some of their own money and are unlikely to loose that much more than their own stake in the course of one day.

Thanks to Ralph Musgrave and Andrew Wilkins, both of you have helped me to have a better understanding of what is happening.

Everywhere I look (read) it is speculation activity that causes gross distortions in average peoples lives. I am confused what good all the speculation does. Policy encourages speculation in esential items of Housing and Food. If speculation was controlled by Fiscal means the rate hot money flowing to individual sectors of the market economy could be controlled to create jobs.

Anyway there seems to be too much money floating around the world that does not create jobs except for Bankers moving the cash arround. As for QE2 if it didnt work for Japan and it didnt work for QE1 who would be stupid enough to doubble up. If the USA want to create jobs it should do what Australia did and send everyone a cheque of say $1000 each per quarter until growth returns. I like Bills idea of the Gov buying the houses and renting them back to the occupier. Its sadens me that a Government does not put shelter for its people above the needs of its speculating class.

I think Macro ideas should be tested in the Micro.

I have wondered how a Post Man could afford to buy a house in Australia. My Nephew is a post man and he cant afford a mortgage that would get him into the lowest priced homes in South East Queensland Australia. There is something very wrong when our service providers who deliver mail to our houses every day cant afford to own a home. Sometimes I think it would be worthwhile having Macro Ideas tested in the Micro using the Post Man test. The test would simply show the real impact on a post mans life of any policy idea. If it works for the Postie it should work for the rest of us.

Thanks for the John Kpiaye link. Going to have a listen now while I wait for the next swell to arrive.

Cheers Punchy

We should be absolutely clear on what the BOE (and the Federal Reserve) is doing. Essentially, they are buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (central bank reserve balances).

I find this proposition somewhat confusing. One of the things I learned here is that private bonds and company paper do not constitute “net financial assets” because each of these things is balanced by a corresponding liability. So if these entities are exchanged for central bank reserves, net financial assets increase, right?

Or do they not increase, because there is now a private sector liability to the central bank to offset the increase in reserves?

Ken

Andrew

Thanks for your comments.

You mention: “From what I see happening here in Asia. QE is driving huge sums of money into Asian stock markets, but not for the reasons you suspect. The rumours are all about hedge funds and investment banks speculation. They are front running clients accounts and “buying the rumour” ahead of fortcoming QE2 announcements.”

Do you see this as net portfolio adjustments amongst these funds and investment banks? Or are commercial banks filtering in their excess reserves through lines of credit or backstops to these funds, albeit in some way that is not immediately showing up in the monetary aggregates, which is increasing the sizes of their bets? Or are their bets funded by net inflows into their funds?

Thanks

I’m sorry William, I don’t have any hard facts and statistics to back up my opinions. I’m in Asia, I read papers and internet articles avidly. I have some contact with folks in the finance trades.

I’d like to think I am an intuitive person who can put a lot of disparate information into a simplified, cohesive and logical argument. I can be hit or miss. I do connect and hit one out of the ball park occasionally. Act on my comments accordingly.

I’d be really stoked if someone backed up one of my intuitive suppositions with empirical proof.

Thanks Andrew.

I suspect though that your on the ground views are more timely and important that what might be cooked up in government statistics–especially any statistics coming out of China.

Andrew & William,

Careful here. Reserve Balances cannot be “driven” or “filtered”, recommend you limit your approach to view them as only debited or credited on bank balance sheets.

Resp,

Good point, Matt. There is no such “thing” as a bank reserve. Reserves are numbers on central bank spreadsheets. They are for settlement in the interbank market, and only those who have access to the interbank market ever encounter them directly in their accounts.

Reserves are not “money” in the conventional sense the public uses, since they are not spent in the economy. Currencies are spent, and if settlement is required, financial institutions settle up in the interbank market using reserves. Settlement transpires on central banks’ spreadsheets, as one reserve account is marked up and another account marked down.

Dan Froomkin interview with Bill Black summarizes Black’s main points on financialization as endemic fraud:

Nine Stories The Press Is Underreporting — Fraud, Fraud And More Fraud

According to Black, this is way beyond rent-seeking. It involves massive and pervasive cheating, driven from the top.

Min says:

“You’ve got that backwards, Ray. The full quotation:

” I do ***not*** mean the following:”

Thanks Min, my bad, I just re-read the text and you are right. Perhaps I am at the crawling stage of MMT as that did not seem to make sense to me as I read it initially.