I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The paranoid style – fiscal consolidation

I happened to re-read an article from the 1960s today – The paranoid style in American politics – written by Richard Hofstadter which was published in the November 1964 edition of Harper’s Magazine. It is one of those articles you should re-read from time to time to remind yourself that not a lot changes. What we call the deficit terrorists now were alive and well then and predicted that anything government amounted to a descent into communism with accompanying mayhem. The facts are clear. The US and most of the world enjoyed positive contribution from government net spending (budget deficits) for most of the post Second World War period and managed to avoid becoming communist (although they might have been better off if they had!). Today, the same paranoia is evident in the interventions into the policy debate from the deficit terrorists. They are so anxious. But underlying their alleged anxiety is a visceral hatred of anything government (except when the handouts are in their favour). None of the calls for fiscal consolidation are based on any firm understanding of how the monetary system works.

Hofstadter said (in 1964):

In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers, who have now demonstrated in the Goldwater movement how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority. But behind this I believe there is a style of mind that is far from new and that is not necessarily right-wing. I call it the paranoid style simply because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy that I have in mind. In using the expression “paranoid style” I am not speaking in a clinical sense, but borrowing a clinical term for other purposes. I have neither the competence nor the desire to classify any figures of the past or present as certifiable lunatics. In fact, the idea of the paranoid style as a force in politics would have little contemporary relevance or historical value if it were applied only to men with profoundly disturbed minds. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant.

If you read his article and cut and paste names and dates you will conclude that nothing much changes. The prophets of doom were out in force then as they are now. The prophets then, fortunately, lived to see their prophecies falsified by history. The current prophets don’t read history and so will have to learn their own lessons in the years to come.

I was thinking about this tendency to promote fear in the public debate today when I was reading several contemporary articles which are predicting that mayhem will accompany a “failure” by governments to reign in their “out of control” budget deficits.

The reality is that most governments need to expand their deficits significantly. But that would require some analytical nous to work out and the paranoid deficit terrorists would struggle to engage in that level of debate.

The right-wing national paper – The Australian always pushes the extremist deficit terrorist arguments to their absurdity. They have been constantly running the line that Australia is now at full capacity and that the budget should already be in surplus given the exploding terms of trade that our nation is currently enjoying.

You pick this sentiment up every time you read articles by its senior economics correspondent Michael Stutchbury. His article today (October 19, 2010) – Productivity retreat won’t ease squeeze – you get more of the same anti-fiscal policy diatribe with lots of spurious logic introduced to deceive readers into accepting the argument.

The basic assertion is that with commodity export prices so strong there is a need to tighten fiscal policy or else the central bank (the RBA) will tighten monetary policy (push up interest rates).

Stutchbury says that:

This commodity price boom is injecting two related shocks into the economy. An export income shock is pumping up national spending power. And a relative price shock is inflating mining development and deflating other sectors.

He should also have said that net exports as a percentage of GDP remain negative meaning that there is a expenditure drain coming from the external sector.

The exchange rate appreciation being driven by the strength of exports and the significant interest rate differential between Australia and elsewhere is introducing deflationary impulses and giving the obsessive RBA some room to delay interest rate rises.

In the Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board in October you read:

The Australian dollar had appreciated by almost 4 per cent over the past month, to be near multi-decade highs against the US dollar and on a trade-weighted basis. Members noted that the appreciation of the exchange rate represented a tightening of domestic financial conditions …

The case to wait before making a tightening move was that the economy was still expected to continue growing at trend in the near term, credit growth had softened somewhat and the rise in the exchange rate would, if it continued, effectively be tightening financial conditions at the margin.

So the appreciation was seen as doing the work that the RBA thinks an interest rate rise would accomplish. The exchange rate appreciation is certainly putting a squeeze on traded-goods sectors which are not enjoying the demand boom in external markets (for example, agriculture and manufacturing).

But the RBA is essentially a boring one-trick pony these days and thinks it has to talk tough on inflation and keeping it under control – even though current inflation is securely within the target band of 2 to 3 per cent and there is no sign of labour costs driving it higher.

There are warning signs emerging from the energy sector

The other side of the appreciating dollar is well presented in this article – Sit back and enjoy the wealth a higher dollar brings – by The Melbourne Age writer Peter Martin (October 19, 2010).

Martin rightfully notes that

Australian consumers are taking great advantage of the strong Australian dollar and the bigger and cheaper markets they can access online. There are fewer losers as a result of our new buying power than once thought.

NEVER let anyone tell you the high dollar is a bad thing. Unless you’re the kind of person who wouldn’t want a pay rise.

The sharp increase in the dollar is boosting the buying power of every dollar we have. If you want proof, go online and check out US dollar prices. The numbers quoted are now identical to those we would have to pay in Australian dollars (before postage and duties where appropriate). Up until now we have had to pay extra. Our money now literally buys more.

If this is making you feel uneasy because the wealth seems unearned, lighten up. When our dollar bought less than half of what it does now (US47.75c in 2001) we accepted the impoverishment with grace.

That is an insight that is contrary to what the mainstream are pumping out each day at present. I was delighted when I was in Europe recently – when I go into supermarkets in Maastricht (where I hang out each year for some time) I typically come out complaining about how expensive everything is. This trip I couldn’t get over how cheap everything appeared in terms of AUD-translated baskets of goods.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) tells you that exports are a cost (we send our real resources abroad for others to use and enjoy) while imports deliver benefits. The more of the latter we can get per unit of the former (that is, the better are the real terms of trade) the better off we all are. An appreciating dollar makes everything we buy from abroad relatively cheaper and is thus is equivalent to a pay rise.

As Martin says – enjoy it while it lasts.

On the sectoral impacts of the appreciating dollar, Martin has a different slant to the right-wing Australian. He says:

What about the losers, you are entitled to ask. I have been asked that in every decade since the dollar was floated. And it gets less of a concern as time goes on. The losers are traditionally said to be Australia’s manufacturers, who compete with imports or try to sell their products overseas.

It’s less of a concern now, in part because there’s less manufacturing than there was.

Martin also points out that agriculture is also enjoy buoyant export prices.

The one sector that has been hit badly is my own – tertiary education. The years of government spending cut backs to education to make it easier to pursue budget surpluses are now coming home to roost. The government forced universities to compete in overseas markets for foreign students which boosted export income but led to a diminution in educational standards here. There have been several scandals in recent years as shonky educational providers have gone broke leaving foreign students stranded.

The higher dollar is now exposing the fragility of the government’s approach to our educational system. If we want to enjoy higher productivity and ease the real constraints that the rising dependency ratio will present in the coming years then we will have to increase domestic funding for education to overcome the suddent funding losses that are now occurring as the exchange rate appreciates and the foreign nations like China develop their own educational strategies and reduce their reliance on foreign provision.

Anyway, Stutchbury claims that the government has introduce “upward spending” biases as it has provided more protection to workers (hardly but a slight improvement on the hideous WorkChoices legislation which finally brought the last conservative government undone and stripped most workplace protections away), and more funding for regional development.

He says:

As a fair go degenerates into “me too”, the upward spending bias clashes with the need to save more of the massive export income windfall and keep the economy within its low inflation speed limit. So official interest rates will shortly shift gears from “neutral” to “restrictive” to quarantine more household spending power into bigger mortgage repayments …

That means the budget needs to be tightened to take more of the burden from interest rates and the dollar

The need for net public spending cuts depends on two things: (a) how close we are to full capacity; and (b) the capacity of the external sector and the private domestic sector to ensure that aggregate demand grows fast enough to fully absorb that capacity on an on-going basis.

The second consideration needs to be further elaborated. When the conservatives took office in 1996 and started pursuing budget surpluses the main instigator of growth was household consumption driven by rising private indebtedness. In fact, the only reason the federal government was able to consistently achieve those surpluses was because the private sector was running up record levels of debt.

In the latter years of the growth cycle (2004-2007), the primary commodities boom also contributed to growth but the private domestic sector still continued to binge on credit. It was an unsustainable growth strategy and came to an end when the global economic crisis emerged in late 2007.

At present, the household sector is lifting its saving rate as a means of reducing its precarious debt-laden balance sheets. Primary commodity prices have recovered and are clearly strong. The question is whether the growth in net exports is strong enough to allow the private domestic sector to net save and fund public services while maintaining aggregate demand at levels which increase capacity utilisation rates and sustain full employment.

That is the question that Stutchbury continually dodges. He thinks his readers will be persuaded by the line that with net exports booming the budget can go into surplus without any other considerations or consequences. It is not that simple unfortunately.

The fact is that net exports are not strong enough to simultaneously support a reduction in private debt and a public surplus while pushing growth to its full employment level. I will demonstrate that point soon.

Stutchbury, however, wants to keep his anti-fiscal policy message simple:

Labor argues that fiscal policy already is tightening as its budget stimulus is withdrawn and gives way to a 2 per cent real spending growth cap and a 2012-13 headline surplus. Interest rates and the dollar are rising because of the mining boom and now the falling greenback, not budget policy.

Yes and no. While budget policy may be tightening, it is too loose to begin with. John Howard and Peter Costello pushed the budget into “structural” deficit by spending too much of the pre-crisis income windfall.

First, note he implies that interest rates changes are not reflective of the state of the budget balance. Next week he will tell his readers that budget deficits are driving interest rates up.

Second, he continually pushes the line that the structural deficit in the lead up to the crisis was too large. I dealt with that often-propagated myth in a previous blog – Structural deficits – the great con job!.

To understand why Stutchbury is misleading his readers you have to understand the make-up of the federal budget balance which is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance cannot be used to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

The reason lies in the operation of the automatic stabilisers. The most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the Budget Balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

Without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

To net out this cyclical impact, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. This was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit is controversial. Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications.

Things changed in the 1970s and beyond. At the time that governments abandoned their commitment to full employment (as unemployment rise), the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

NAIRU theorists then invented a number of spurious reasons (all empirically unsound) to justify steadily ratcheting the estimate of this (unobservable) inflation-stable unemployment rate upwards. So in the late 1980s, economists were claiming it was around 8 per cent. Now they claim it is around 5 per cent.

The NAIRU has been severely discredited as an operational concept but it still exerts a very powerful influence on the policy debate. In Australia, it dominates the Treasury and the Reserve Bank modelling.

The NAIRU is now used to define full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then the conservatives claim that the economy is at full capacity. Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

But they still persist in using it because it carries the ideological weight – the neo-liberal attack on government intervention.

In the past, full capacity was achieved when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels. The use of the term structural balances abandoned that meaning of full capacity which is now equated with an economy operating at the NAIRU, even if the latter evades meaningful measurement.

The structural balance is thus estimated by basing it on the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This technique severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending and thus concludes the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is.

They thus systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

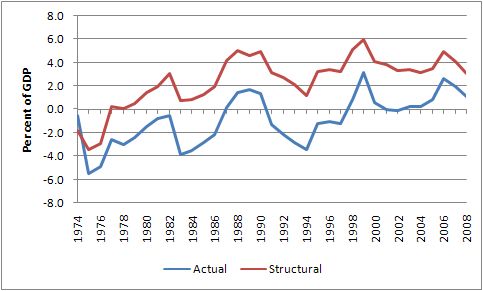

The following graph is indicative of this bias. It appeared in Budget Statement 4: Assessing the Sustainability of the Budget:

I noted that the Stutchbury had previously used the same Treasury graph above in an earlier article – Swan’s surplus of silence – and did not tell his readers about this underlying bias in the calculations.

He should have because it would have influenced the way his readers interpreted and judged his article. They would have thought it a poor piece of journalism if they knew the basis of the discussion.

This is an example of the decomposition of the federal budget balance into cyclical and structural factors. According to the Treasury:

Based on these estimates, the structural budget balance deteriorated from 2002-03, moving into structural deficit in 2006-07. This shows that the actual underlying cash balances in previous years were primarily the result of the strength in Australia’s terms of trade, which increased by almost 40 per cent over this period. While the temporary fiscal stimulus measures result in a widening of the structural deficit, the deficit narrows over the medium term reflecting savings measures and the Government’s commitment to reduce spending as the economy recovers.

What they are saying is that the surpluses in the years prior to the crisis were not structural but were driven by cyclical factors – the booming commodities prices. They are also saying that the underlying or structural budget has gone into deficit due to the discretionary changes of the Federal Government (the stimulus packages) and that by 2015-2116, the structural balance will be back in surplus. The falling deficit is projected on the basis of discretionary decisions made by the government to reduce outlays over this period.

Stutchbury is just rehearsing this hackneyed interpretation of the official data.

But of-course, given the earlier discussion, this is all dependent on what you call “full capacity”. At the time the economy was meant to be at full capacity there were at least 9 per cent of willing and available labour resources idle (either unemployed or underemployed). I do not call that a full employment situation.

I define full employment as an economy that delivers as many jobs as their are people wanting them and hours of work consistent with the desired hours of the workers. In other words, an economy that has an unemployment rate around 2 per cent (which allows for frictions – people moving between jobs) and zero underemployment. That is a far cry from the “full capacity” dodges used by the OECD, the IMF and the Australian Treasury. Their conceptions of full capacity are ideologically-loaded by the NAIRU concept and are frankly … a total joke.

If you estimate what the structural balance would be with an unemployment rate of 2 per cent you get a very different version of the history of the structural deficit. In this blog – Structural deficits – the great con job! – I outline a methodology to accomplish this task.

I ignored the fact that underemployment is rising and so my estimates significantly underestimated the full capacity position of the economy and as a result underestimated any structural surpluses that I calculated.

The following graph shows you the actual operating results (Total Revenue minus Total Spending) since 1974 and the structural operating balance (computed as above) based upon a more realistic estimate of full capacity. The difference between the structural and the actual reflects the fact that over this period the economy has never operated at 2 per cent unemployment. The difference between this estimate of the structural balance and the Treasury’s estimate lies in the fact that they are assessing full capacity at a much higher unemployment rate – which is not the full employment level of the economy.

So the Treasury estimates of the structural balance build in the assumption that the Government will not achieve anything remotely like full employment over the period shown in the graph. By the time the graph is crossing the zero line again (in several years) the economy will be at the NAIRU or around 5 per cent unemployment. That is not admitted in any of these public documents nor by the journalists.

If you examine my graph you can see the actual balance (blue line) is well below the estimated structural balance (red line). The Federal Government has been running contractionary budget positions (structurally) since 1976. So the deficits over the period (1974 to 2008) are entirely cyclical and reflect the fact that rising unemployment drove the automatic stabilisers sufficiently against the contractionary bias in the budget to generate the deficits.

You can also see that the budget surpluses in the recent years were structural. They were not driven by the commodity prices alone as the Treasury is trying to tell us. The previous federal regime was running hugely contractionary positions during this time and relying on the private credit binge for growth. This was an unsustainable growth strategy and the height of fiscal irresponsibility. We are suffering the consequences of it now.

It should also be apparent that the swing in net spending (from the structural surpluses) to a structural deficit (which will be required for sustainability to finance private net savings) will be huge. That is, if we seriously consider full capacity to be when every one has a job!

What this tells me is that budget deficit currently is way to small as a percentage of GDP. The structural budget that the Government is coming from was very contractionary.

The conservatives try to con us by equating the full capacity position with the NAIRU. Commentators like Stutchbury then start claiming (spuriously) that the budget is too expansionary when in fact it will likely still be contractionary.

Stutchbury continues that:

Labor’s rapid “fiscal consolidation” is mostly cyclical and painless. By now the budget should be in surplus given the China boom has pushed the terms of trade to a 60-year high and the economy close to full capacity. Treasury says the budget will remain in structural deficit until 2019, suggesting we’ve already spent too much of the income windfall.

McKibbin says “all tools of policy” need to be more sharply applied to “the key issue facing the country, that is the resources boom”. A fiscal policy review should be a “key priority” because current budget settings are designed for “a recession that never came”.

I considered the views of McKibbon (a professor at the Australian National University) in this blog – GIGO …. The title of that blog – Garbage In, Garbage Out – will tell you what I think of this views.

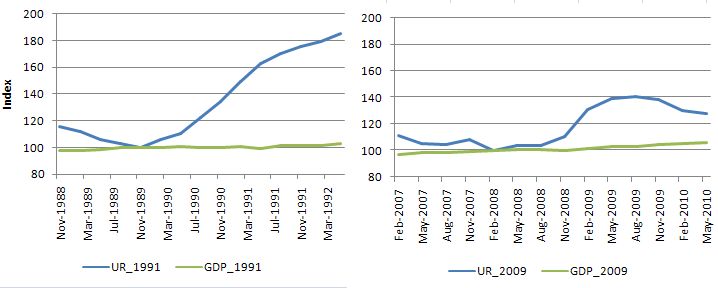

First, the recession did come and the fiscal policy intervention attenuated its consequences. The following graph compares the 1991 and 2009 recessions. The index base (100) are set for the low-point unemployment rate in each cycle (November 1989 and February 2008) and the graphs are drawn for the period 4-quarters before the low-point and 10 quarters after. The two series are the unemployment rate (blue) and GDP (green). The vertical scales are the same to show the comparison.

You can see that the failure of the government to react to the 1991 downturn with a speedy fiscal intervention caused the labour market to deteriorate sharply. The unemployment rate kept rising for four more quarters after the end of the period shown. In the current episode, the rise in the unemployment rate though sharp was attenuated quickly by the fiscal intervention.

The graph also shows you clearly that the labour market deterioration is drawn out (even in 2009) and remains an issue long after GDP growth has returned. It is why a job creation strategy should be used early in the policy response period.

It is also interesting to examine the claim that net exports are likely to be so strong that we can afford to have an overall expenditure drain from the public sector.

In this blog – Norway … colder than us but … – I examined some facts about Norway which does run budget surpluses but still enjoys a very high standard of living.

In a later blog – Norway and sectoral balances – I looked more explicitly at the sectoral balances in that nation.

Norway is a small open economy like Australia and is one of the World’s largest oil exporters. They have been flooded with export revenue as energy prices soared over the last few years. Their case is special because it highlights a situation where an economy can grow even though the public sector is running surpluses without increasing indebtedness in the private domestic sector.

I have often introduced the sectoral balances view of the national accounts in my blogs. You can find a derivation in the blog – Norway and sectoral balances.

There are three sectoral balances: the Budget Deficit (G – T), the Current Account balance (X – M) and the private domestic balance (S – I). These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

You can then manipulate these balances to tell stories about what is going on in a country of interest.

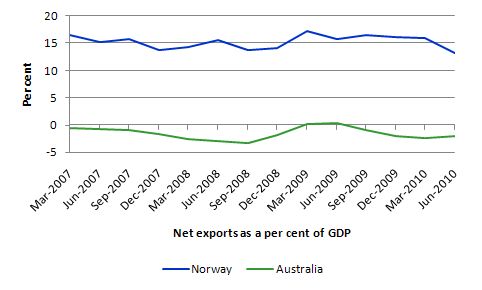

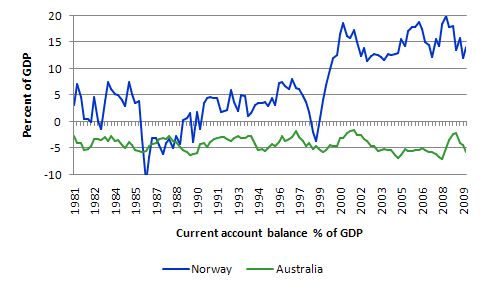

Norway is currently running huge net export surpluses. Consider the following graph which compares Net exports as a % of GDP for Australia and Norway from March 2007. The data is from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and Statistics Norway.

There is no comparison. Australia does not typically enjoy a positive contribution from net exports while Norway clearly does.

Generalising to take into account the invisibles on the current account, the following graph is taken from OECD Main Economic Indicators data and shows the Current Account balance as a per cent of GDP.

So the external sector overall makes a positive contribution to Norwegian GDP growth while the Australian external sector overall, booming commodity prices in recent years notwithstanding, makes a negative contribution to Norwegian GDP growth.

Norway also enjoys strong private domestic surpluses (S – I). The data from Statistics Norway shows that in 2003 the private saving ratio was 9.2 per cent of GDP and this peaked at 10.1 per cent in 2005 and has since declined to 7.9 per cent. For Australia, the household saving ratio in June 2010 was only 1.9 per cent and was regularly negative in the period that the federal government was running budget surpluses.

Using the sectoral balance framework, we can say that a current account surplus (X – M > 0) allows the government to run a budget surplus (G – T < 0) and still allow the private domestic sector to net save (S - I) > 0. In fact, the budget surplus is ensuring that the total net spending injection to the economy matches the spending gap derived from the desire to save. If the government tried to run deficits in this case, then spending overall would be too large relative to the real capacity of the economy and inflation would result.

So, as a matter of accounting between the sectors, a government budget deficit adds net financial assets (adding to non government savings) available to the private sector and a budget surplus has the opposite effect. The last point requires further explanation as it is crucial to understanding the basis of modern money macroeconomics.

In aggregate, there can be no net savings of financial assets of the non-government sector without cumulative government deficit spending. In a closed economy, NX = 0 and government deficits translate dollar-for-dollar into private domestic surpluses (savings). In an open economy, if we disaggregate the non-government sector into the private and foreign sectors, then total private savings is equal to private investment, the government budget deficit, and net exports, as net exports represent the net financial asset savings of non-residents.

It remains true, however, that the only entity that can provide the non-government sector with net financial assets (net savings) and thereby simultaneously accommodate any net desire to save (financial assets) and thus eliminate unemployment is the currency monopolist – the government. It does this by net spending (G > T).

Additionally, and contrary to mainstream rhetoric, yet ironically, necessarily consistent with national income accounting, the systematic pursuit of government budget surpluses (G < T) is dollar-for-dollar manifested as declines in non-government savings. If the aim was to boost the savings of the private domestic sector, when net exports are in deficit, then taxes in aggregate would have to be less than total government spending. That is, a budget deficit (G > T) would be required.

Conclusion: Norway is in an atypical situation – being swamped with net export spending injections.

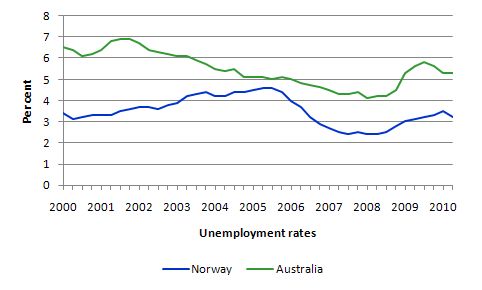

So if we usually have a current account deficit (X – M < 0) then for the private domestic sector to net save (S - I) > 0, then the public budget deficit has to be large enough to offset the current account deficit. As a matter of accounting if (S – I) < 0 then the domestic private sector is spending more than they are earning (dis-saving). In this situation, the fiscal drag from the public sector is coinciding with an influx of net savings from the external sector. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. It is an unsustainable growth path. This situation describes the recent history of Australia. The other point relates to capacity utilisation. The following graph compares the OECD MEI unemployment rates for Australia (green) and Norway (blue). It is clear that Australia fails to match the low unemployment rates that Norway enjoys. Further, Australia's underemployment rates are much higher than the low rates enjoyed by Norway. In the blog - Norway … colder than us but … – I explain some of the differences in the institutional environment between the two nations which promote lower unemployment rates in Norway.

Historically, Norway experienced the same cycles in 1982 and 1991 as Australia, but the severity of the effect was much lower. In fact, in the 1991 recession the Norwegian high-point unemployment rate barely made it above the level that we started that recession with. The Norwegian government introduced a large public works programme followed including the fast-tracking of the new Oslo international airport at Gardermoen to combat the 1991 recession. The Australian government was largely inert in the early period of that recession and the consequences were dire.

A significant aspect of Australia’s failure to keep unemployment low has been the role of our public sector vis-a-vis that of Norway. The public sector in Norway is a major contributor of employment in their economy.

It has often been stated by neo-liberals that the reason our unemployment rate rose over the last three decades was because of the increased participation of women and the rise of the service sector. There were many spurious arguments used to justify these claims which I won’t rehearse here. But Norway had one of the highest rises in female participation rates since the mid-1970s and also faced the decline in manufacturing and related industries as their service sector grew.

The big difference is that while our service sector is expressed by the growth in “burger flipping” employment – casualised, low-skill, low-pay and going nowhere, in Norway, the public sector was a major source of service sector employment growth. These jobs were in personal care services, health, education and the like. Typically secure, well-paid skilled jobs that allowed that country to absorb these structural changes without the significant increases in unemployment or inequality that have marked Australia’s industrial shifts since the 1970s.

Further, by increasing the share of public employment in total employment, the Norwegian government has been able to use the public sector as a means to keep unemployment low and absorb the structural and cyclical shocks much better than us.

Further, in Norway long-term unemployment is defined as being unemployed for more than 26 weeks whereas in Australia we consider spells of unemployment greater than one year to represent long-term unemployment. This means that more intensive assistance is given to the LTU worker in Norway much sooner.

Norway, like most Scandinavian countries considers its youth to be the future. In Australia, we allow our youth to wallow in high states of unemployment accompanied by no formal schooling/training requirements. In Norway, they targetted youth specifically with their Youth Guarantee which ensures that all youth between 20 and 24 years of age will be either employed; participating in formal education or receiving trade training.

To address this issue, the Norwegian Government guarantees all youth below 20 years of age support for 3 years of upper secondary education. All those who leave upper secondary school and who are unemployed are immediately subsumed by the Youth Guarantee into a paid job (typically public sector) or a skills development program (which could be in the context of paid employment).

Finally, unlike Australia which privatised the provision of labour market services and fragmented job matching, intensive assistance, training, welfare support etc, Norway retained these functions within the public sector. They do not seek to make profit or create an industry from the unemployment as has been the case in Australia.

Conclusion

The point is that it is hard to make the case that with 12.5 per cent of willing labour resources idle at present that we are close to full capacity. Further, the private domestic sector has not yet achieved a significant reduction in its indebtedness and that process needs to continue.

The question then is whether the commodities boom will drive net exports up enough to “finance” the private domestic saving (and deleveraging), while keeping growth strong enough to absorb the idle labour and allow the government to achieve a budget surplus.

While Australia is enjoying very high commodity prices, net exports are nowhere near strong enough to support robust economic growth without some fiscal support remaining. We are not Norway which enjoys high standards of living, a very substantial public contribution to employment and high saving ratios while running budget surpluses.

The budget surpluses in Norway are required to keep aggregate demand contained within the inflationary constraint. But the economy enjoys strong growth and low unemployment.

Australia is nowhere near being in that situation and net exports will not get us there notwithstanding the high commodity prices. Stutchbury clearly doesn’t understand that point and just lets his blind hatred for budget deficits get in the way of reasoned commentary. He is just a practitioner of the paranoid style!

That is enough for today!

“But the RBA is essentially a boring one-trick pony these days and thinks it has to talk tough on inflation and keeping it under control – even though current inflation is securely within the target band of 2 to 3 per cent and there is no sign of labour costs driving it higher.”

They are sounding like that aren’t they? One wonders what they have to fear when the rest of the world’s central bankers would give their left testicles to have inflation around 2.75%. The way the banks are talking about jamming an extra 20-30bps onto the next 25bp official hike (50bps to the consumer) will surely take retail rates north of neutral. More upwards pressure on the AUD, more moaning from Bob Katter et al.

Even if CPI sat at 3-3.25% (which it won’t as the AUD further appreciates), who really cares for the next couple years?

I’m with you on this one Bill.

“The US and most of the world … managed to avoid becoming communist (although they might have been better off if they had!).”

I’m assuming that’s a joke?

Gotta love that great Russian communist quality of life post-war. I wonder if they would let you blog to your heart’s content about the ‘qualities’ of your comrade leaders.

The RBA has been hampered by a lack of political will to rein in the credit fuelled housing bubble.

Successive Governements had many opportunities to curb credit growth and house prices since the bubble started to form in 2003/4. Tweaks to Negative gearing or capital gains tax could have sustained house prices close to long term rental yields and income multiples.

Short term populist leadership makes poor economic decisions.

Indeed AW, no backbone by the political parties means the RBA is left to use monetary policy to solve all.

No PM is going to lightly remove negative gearing or the tax-free status of own homes.

Notice how quiet the Obama administration is during the whole Fed’s QE experimentation? If it works (which it won’t) then Obama takes credit and if it doesn’t then give Bernanke the flick.

Australia could quite happily live with $20bn spent on a huge upgrade of communications (NBN-lite) and the remaining 23bn spent on new housing, hospitals, transport and other more urgent programs. Maybe even a few pennies left for Bill’s JG experiment.

If it works (which it won’t) then Obama takes credit and if it doesn’t then give Bernanke the flick.

More likely that voters will give Obama the flick in ’12. BTW, once appointed by the president and confirmed by the senate, the Fed chair/BoG are accountable to no one. That’s what “cb independence” means.

There’s a good bit on Paranoia in National/Public life in “Life and how to survive it.” By Robin Skinner and John Cleese.

Bill “The government forced universities to compete in overseas markets for foreign students which boosted export income but led to a diminution in educational standards here.”

Do you consider having foreign students an inherently bad idea? I kind of thought it meant that domestic students would also benefit from exposure to those from other countries and cultures who were keen to learn. After all your blog has a global readership and you seem to travel the globe interacting with other economists from many different countries. Have I misunderstood you?

Tom Hickey says:

Wednesday, October 20, 2010 at 1:28

“BTW, once appointed by the president and confirmed by the senate, the Fed chair/BoG are accountable to no one. That’s what “cb independence” means.”

Indeed, I mentioned here last week that US policymakers should strip some powers from the Fed (for the near term at least) so that they are not forced to perform all manner of witchcraft which they think is worth a shot to hamper disinflationary forces and lower unemployment.

Clearly the Fed has done its bit and easy credit is not the sole answer, time for some bi-partisan fiscal measures again. Another couple of Hoover dam project perhaps.

Stone,

Australian Universities have lowered standards in an effort to increase enrolments from foreign full fee paying students.

To lower academic standards to increase business defeats the purpose of higher learning in the first place.

Bill may be many things but he’s certainly not xenephobic as you seem to be implying.

cheers.

Don’t the fees earned from foreign education (isn’t this like one of Australia’s top export earners??) find their way back into schools and universities in the form of improved facilities and thus improve education for all involved?

Where is the evidence that standards have dropped and it would be interesting to see the average grades of ‘locals’ vs foreigners.

In reality, Australian students are heavily subsidised by the taxpayer to complete their studies and I wonder if their fees ought to rise if not for the foreign students paying market rates.

Ray,

“In reality, Australian students are heavily subsidised by the taxpayer to complete their studies and I wonder if their fees ought to rise if not for the foreign students paying market rates.”

I see what you mean….. The fees from foreign students, allows economies of scale in the Australian education system. That benefits domestic students directly and also boosts the economy.

You won’t be getting any MMT awards for the composition of your sentance 🙂 ….. Taxpayer funding ????

“At present, the household sector is lifting its saving rate as a means of reducing its precarious debt-laden balance sheets. Primary commodity prices have recovered and are clearly strong. The question is whether the growth in net exports is strong enough to allow the private domestic sector to net save and fund public services while maintaining aggregate demand at levels which increase capacity utilisation rates and sustain full employment.”

Could someone comment on the “fund public services” point above? I think I followed the rest of the blog entry, but I’m not certain how to work out the funding of public services in the MMT sense. Thanks!

Ray,

“In reality, Australian students are heavily subsidised by the taxpayer to complete their studies and I wonder if their fees ought to rise if not for the foreign students paying market rates.”

In reality, Australian businesses are heavily subsidised by the taxpayer who ensure an ample supply of skilled labour is readily available at an affordable price, allowing business to leverage off these skills. If skilled labour was much more scarce, the cost of labour would soar in terms of market rates.

Aaron says:

Wednesday, October 20, 2010 at 18:05

“In reality, Australian businesses are heavily subsidised by the taxpayer who ensure an ample supply of skilled labour is readily available at an affordable price, allowing business to leverage off these skills. If skilled labour was much more scarce, the cost of labour would soar in terms of market rates.”

I see your counter argument (sort of), but if you are implying that subsidised student education is really an ultimate subsidy to business then we can always vastly increase immigration quotas for skilled/educated workers and get their education for free, no? Maybe pay Australians to not have kids.

Ray: “Don’t the fees earned from foreign education find their way back into schools and universities in the form of improved facilities and thus improve education for all involved?”

This would happen if government maintained funding levels and institutes could treat funding from international students as a ‘bonus’, however during the boom in international student numbers government funding per student decreased. Commonwealth funding per subsidised higher education student was 10% lower in 2008 than 1996 in real terms (Bradley Review, p.144).

In VET the decline per publicly-funded hour was even higher. In VET, 85% of international students go with private providers, many of which are established to cater for them specifically. So the returns to TAFEs from international students in VET have not matched the decline in state and commonwealth funding per student hour.

The point is that providers are no more resourced per student than before, plus they are having to cater to a number of students who require more support than others.

Ray: (isn’t this like one of Australia’s top export earners??)

Yes it is the largest services export industry, but only when including ancillary income such as living expenses, tourist trips by friends and relatives, etc. There is some debate about how this should be treated, as fees make up less than half of the amount and it doesn’t take into account onshore earnings of international students, etc.

Ray: Where is the evidence that standards have dropped

The Baird Review has some (careful) discussion of this, particularly in relation to the VET providers Bill refers to in this post.

Ray: it would be interesting to see the average grades of ‘locals’ vs foreigners.

It would be, and there would probably be lots of variation between fields of education. But it wouldn’t necessarily allow us to know whether and quality has changed over time and if growth in international student numbers was the cause. It wouldn’t show whether courses or assessment have changed over time to accomodate overseas students in the courses they are highly represented in, for example. A 203 study showed that course completion rates were significantly higher for overseas students at TAFE, but overseas students have more motivation to complete full qualifications in VET than domestic students who can complete a module which provides them with a skillset that makes them employable in a particular field.

Ray: Australian students are heavily subsidised by the taxpayer to complete their studies and I wonder if their fees ought to rise if not for the foreign students paying market rates.

International students pay well over the cost of delivery, so yes their fees do provide some ‘subsidy’, but as discussed above, not enough to counter the relative decline in government spending.

There are many benefits from international students, but the rate of growth coupled with declining funding in real, per-student terms, has affected class sizes, teacher quality, etc. to various extents in different sectors and institutions.

Patrice Meursault says:

Wednesday, October 20, 2010 at 18:50

great post and full of lots of good info. Thank you.

Will be interesting also to see in a year or so just how much the foreign student demand falls due to AUD strength though the effect vs the Rupee and Yuan has been less than against some other of the relevant currencies.

Ray even if the students are from China and India, I guess Australia is in competition with UK and USA for their custom so I guess the AUS$ to USD and UK£ exchange rates do matter. Since the foreign students pay more than cost I don’t see the logic in Bill mentioning them when bemoaning reduced government funding for Australian students. All other things being equal, it would be much worse were it not for the foreign students.