I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The government is the last borrower left standing

Remember back last year when the predictions were coming in daily that Japan was heading for insolvency and the thirst for Japanese government bonds would soon disappear as the public debt to GDP ratio headed towards 200 per cent? Remember the likes of David Einhorn – see my earlier blog – On writing fiction – who was predicting that Japan was about to collapse – having probably gone past the point of no return. This has been a common theme wheeled out by the deficit terrorists intent on bullying governments into cutting net spending in the name of fiscal responsibility. Well once again the empirical world is moving against the deficit terrorists as it does with every macroeconomic data release that comes out each day. I haven’t seen one piece of evidence that supports their view that austerity will improve things. I see daily evidence to support the position represented by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Anyway, there was more evidence overnight that I thought should be mentioned and relates to the idea that “the government is the last borrower left standing”.

Einhorn gave a speech to the Value Investing Conference on October 19, 2009. I note he is a keynote again this year so the organisers obviously haven’t been keeping track of events to realise that this guy’s predictions have been way off the mark.

Einhorn’s speech was entitled – Liquor before Beer … In the Clear – and he began by outlining what he thought were the “macro risks we face” in the investment context.

He rehearses all the known arguments of the deficit terrorists – inflation, debt-default etc. Then he gets to Japan and says:

Japan appears even more vulnerable, because it is even more indebted and its poor demographics are a decade ahead of ours. Japan may already be past the point of no return. When a country cannot reduce its ratio of debt to GDP over any time horizon, it means it can only refinance, but can never repay its debts. Japan has about 190% debt-to-GDP financed at an average cost of less than 2%. Even with the benefit of cheap financing the Japanese deficit is expected to be 10% of GDP this year. At some point, as American homeowners with teaser interest rates have learned, when the market refuses to refinance at cheap rates, problems quickly emerge. Imagine the fiscal impact of the market resetting Japanese borrowing costs to 5%.

Over the last few years, Japanese savers have been willing to finance their government deficit. However, with Japan’s population aging, it’s likely that the domestic savers will begin using those savings to fund their retirements. The newly elected DPJ party that favors domestic consumption might speed up this development. Should the market re-price Japanese credit risk, it is hard to see how Japan could avoid a government default or hyperinflationary currency death spiral.

Greenlight – Einhorn’s investment company – is known to have bought long-dated options on much higher interest rates in Japan which if rates rise significantly over the next four odd years will give it large profits. The counterparty was the major banks and I expect them to make the money.

When people are talking big like this we need to look at the data.

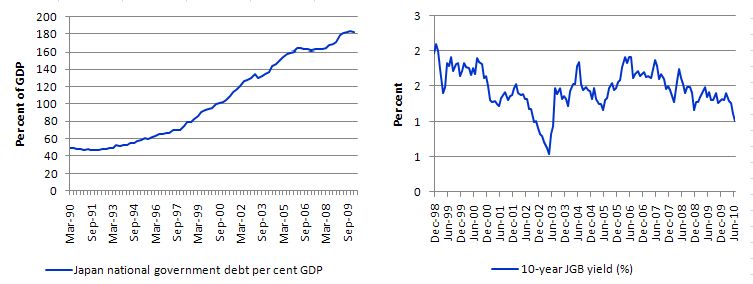

The first graph shows the national debt to GDP ratio since early 1990 to March quarter 2010 (left-panel) and the 10-year Japanese government bond yield since December 1998 (there was a break in the official series in November 1998). You can get Bank of Japan data for 10 year government bond yields back to October 1985. The choice of sample is immaterial.

So I wouldn’t be betting against rates rising anytime soon in Japan.

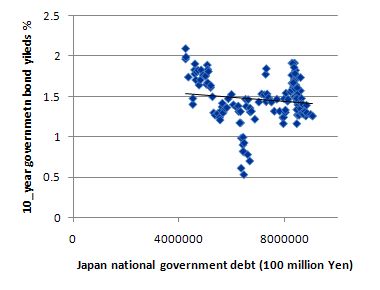

And what about the relationship between the debt ratio and the bond yields? The following graph plots the volume of outstanding national government debt (100 millions) (horizontal axis) against the 10-year JGB yield. The black line is a linear regression (sloping down!).

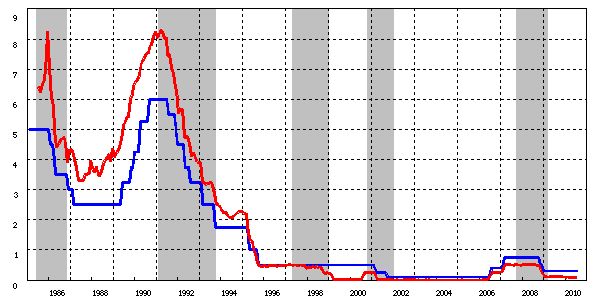

Short-term rates have also been very low in Japan for a very long time. This graph is from the Bank of Japan database and the red line is the overnight call rate and the blue line is the basic discount rate. The grey bars are official (GDP) recessions.

The conclusion is obvious. The BOJ controls short-term rates and has kept them at around zero for years. I could have plotted inflation rates which would have shown low and stable inflation for many years bordering on a deflationary problem arising from deficient economic activity.

Anyway, I will close my blog down immediately and apologise profusely for being a dingbat if JGB yields skyrocket in the next five years.

I also wonder how the Einhorn’s take in the regular news on the latest JGB auction results.

The Japanese JiJi financial news service carried an item overnight that caught my attention this morning and was the source of a few E-mails (thanks Marshall!):

Tokyo, Aug. 4 (Jiji Press)–Japanese government bonds rose sharply in Tokyo Wednesday amid growing uncertainties about the U.S. economy, with the yield on the benchmark 10-year issue slipping through the one pct threshold for the first time in seven years. In late interdealer cash trading, the yield on the latest 309th 10-year JGB with a 1.1 pct coupon stood at 0.995 pct, a level unseen since early August in 2003 and down from 1.020 pct late Tuesday.

So the demand for JGB rose for this issue as the total stock of bonds (absolutely and relative to GDP) continued to rise.

A bit later Nikkei reported that Long-Term Rates Climb Back Above 1%. Heavens I thought – bond yields are nearly going through the roof!

TOKYO (Nikkei)–The benchmark 10-year government bond yield rose to 1.015% Thursday morning as eased worries over the U.S. economic slowdown prompted investors to sell the safe-haven asset.

On Wednesday, the bond yield fell below the 1% line for the first time in about seven years, hitting 0.995%.

Read carefully: this is saying that financial market investors got less nervous and decided a bit more risk was tolerable so they sold the “safe-haven asset” (the Japanese government debt) and rates rose just a tad.

No Einhorn scenario is likely yet. When? Answer: never!

So why do the commentators and the insiders like Einhorn get it so wrong?

First, they don’t fully understand how the macroeconomy works. Most of their knowledge would come from either mainstream macroeconomics course at universities which worthless (actually damaging) or around lunch tables sipping cups of tea sharing “knowledge” with similarly blighted individuals.

Second, they therefore do not understand the nature of the problem at present. They think the problem is the “size” of the public deficits and the growing ratio of public debt to GDP but a considered reflection leads one to conclude these are not problems at all. The movements in these aggregates tells us about other problems – pertaining to the real economy – but in and of themselves they present no issue that is worth a moment’s thought.

The problem for the public debate though – in terms of moving it in a direction that will address the actual underlying issues such as weak aggregate demand and persistently high unemployment and rising long-term unemployment – is that these commentators are stuck in mindless obsessive warp about these financial ratios. They cannot see beyond them and they cannot see how meaningless their daily obsessions are.

Which brings me to the hearings that were conducted last week by the US Committee on Financial Services, which is a committee of the US House of Representatives.

On July 22, 2010, Richard Koo appeared before the Committee and presented his testimony – How to Avoid a Third Depression. I have previously considered Koo’s ideas in this blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy.

Essentially, his views have resonance with the main perspectives offered by MMT although he does get some things wrong.

His recent testimony is one of the better commentaries on the current economic problems but probably fell on deaf (or dumb) ears at the hearing.

Koo told the hearing that there are recessions and then there are depressions. The correct policy response must differentiate correctly between these two economic episodes. He said:

The key difference between an ordinary recession and those that can lead to a depression is that in the latter, a large portion of the private sector is actually minimizing debt instead of maximizing profits following the bursting of a nation-wide asset price bubble. When a debt-financed bubble bursts, asset prices collapse while liabilities remain, leaving millions of private sector balance sheets underwater. In order to regain their financial health and credit ratings, households and businesses in the private sector are forced to repair their balance sheets by increasing savings or paying down debt, thus reducing aggregate demand.

So while the ultimate problem remains a deficiency of aggregate demand (total spending) the balance sheet dynamics in the private sector are also important to understand.

When we talk about deficient aggregate demand we are considering spending in relation to the capacity of the economy to produce real goods and services. This can also be viewed of as the capacity to employ workers at current productivity rates. So deficiency is a shortfall in spending which provokes firms to reduce output (so that they do not accumulate unsold inventories) and lay off workers.

All recessions have this dynamic. Private spending falls perhaps because firms feel negative about the future growth in sales. Perhaps the fall in private spending originates as reduced consumption. Either way, overall aggregate demand falls.

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next notes that output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms lay-off workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession.

So the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur. This could come from an expanding public deficit or an expansion in net exports. It is possible that at the same time that the households and firms are reducing their consumption net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public budget balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving ratio if net exports were strong enough.

However, what Koo calls the depression-route is also associated with huge levels of private indebtedness that has to be cleared before private spending growth can occur. The balance sheet urgency complicates the recovery process and make the policy intervention even more critical because private saving has to be supported to allow the balance sheet corrections to occur.

Koo notes that in these circumstances (private debt minimisation) monetary policy becomes ineffective:

… because people with negative equity are not interested in increasing borrowing at any interest rate. Nor will there be many lenders for those with impaired balance sheets, especially when the lenders themselves have balance sheet problems.

From a MMT perspective, monetary policy has dubious effectiveness anyway because it is highly dependent on the reactions of creditors (facing low incomes) and debtors (facing higher incomes). The timing and magnitude of these spending reactions are unclear. Further, monetary policy is a blunt instrument and cannot be targetted at all.

But Koo’s insight remains interesting and relates to what Keynesian economists have called a “liquidity trap” – where all people form the view that interest rates can only rise and so hold their speculative wealth balances as cash rather than bonds (because they fear the bond prices will fall). At that point credit creation stalls and interest rate manipulation is futile.

But Koo’s point should also be extended to note that the claims by central bankers and others that their quantitative easing policies would expand credit were always misleading if not plain wrong. Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

You might also like to review the blogs – Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion of the way in which monetary policy changes in recent years have been seriously misunderstood by commentators (for example, Einhorn and his ilk).

Koo then draws out the implications of this situation:

… when the private sector de-leverages in spite of zero interest rates, the economy enters a deflationary spiral because, in the absence of people borrowing and spending money, the economy continuously loses demand equal to the sum of savings and net debt repayments. This process will continue until either private sector balance sheets are repaired, or the private sector has become too poor (=depression) to save any money.

He is assuming no government response other than via automatic stabilisers and no change in the external position of the economy. You will note that the austerity proponents, in part, claim that the withdrawal of public spending will be partially or more than partially offset by improving net export positions as competitive gains arise from cutting domestic wages and prices.

There is very little chance of that happening on a global scale with all nations being bullied into austerity. The single-country/single episode examples they wheel out to “prove” that austerity has worked in the past are not only flawed in themselves but ignore the implications of all nations doing the same thing at the same time.

Please read my blog – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition – for more discussion on this point.

But his point is sound. The problem we have been facing for several years now (about three) is that the credit binge that preceded this crisis has left a lot of private consumers and investors in diabolical straits with too much nominal debt and declining values of the assets the debt backed.

The need to remedy this problem led to a widespread withdrawal of private spending as the pessimism of future growth spread and the expenditure multipliers reverberated this pessimism across the world economies. Please read my blog – Spending multipliers – for more discussion on this point.

So what started as a financial problem spread into the real economy via the negative spending reactions and the multiplier mechanism. The latter always drives recession whereas the former instigation is not always present.

Koo gives an easy example to understand this process:

To see this, consider a world where a household has an income of $1,000 and a saving rate of 10 percent. This household would then spend $900 and save $100. In the usual or textbook world, the saved $100 will be taken up by the financial sector and lent to a borrower who can best use the money. When that borrower spends the $100, the aggregate expenditure totals $1,000 ($900 plus $100) against the original income of $1,000, and the economy moves on. When demand for the saved $100 is insufficient, interest rates are lowered, which usually prompts some borrowers to take up the remaining sum. When the demand is too large, interest rates are raised, which prompts some borrowers to drop out.

In the world where the private sector is minimizing debt, however, there will be no borrowers for the saved $100 even with zero interest rates, leaving the economy with only $900 of expenditure. That $900 is someone’s income, and if that person saves 10 percent, only $810 will be spent. But since repairing balance sheets after the bursting of a major bubble typically takes many years (it took 15 years in Japan), the saved $90 will go unborrowed again, and the economy will shrink to $810, and to $730, and so on.

While I am not really enamoured by this representation of the banking system, the dynamic is accurate. The shrinkage in spending is the multiplier in action.

Koo then argues that “Japan faced the same challenge following the bursting of its bubble in 1990, when it lost wealth equivalent to three years worth of GDP on shares and real estate alone (the U.S. lost wealth equivalent to one year’s worth of 1929 GDP during the Depression)”. He reported that “net debt repayment in the corporate sector shot up to more than 6 percent of GDP a year … on top of household savings of over 4 percent of GDP, all with interest rates at zero percent. In other words, Japan could have lost 10 percent of GDP every year, just as the US did during the Great Depression”.

He says that:

Japan managed to avoid the depression, however, because the government borrowed and spent the aforementioned $100 every year, thereby keeping the economy’s expenditure at $1,000 ($900 household spending plus $100 government spending). In spite of nationwide commercial real estate prices falling 87 percent from their peak, Japan managed to keep its GDP above the bubble peak throughout the post-1990 era … Its unemployment rate never went beyond 5.5 percent, either. Private sector balance sheets were also repaired by 2005.

While we talk a lot about the lost decade in Japan the reality is that the government fiscal intervention which was very signficant in relative terms stopped that decade from being a total disaster. The private sector made huge losses but the damage was contained and the fiscal intervention created the conditions whereby the healing was quicker.

The fiscal intervention allowed (“financed”) the increased private saving desires by maintaining demand and hence GDP growth at much higher levels than if the government had not changed policy tack in favour of expansion.

The MMT quibble would be that the characterisation of the government borrowing to spend is erroneous. What happened was that the government spend and then borrowed back some but not all of the bank reserves that the spending ultimately generated. By leaving some excess liquidity in the banking system (that is, borrowing less than the reserves created by the on-going fiscal intervention), the Bank of Japan was able to hold short-term rates at zero (as shown in the graph above).

There was also an private appetite for buying the bonds because they are riskless and offered a yield slightly above the zero on offer from cash holdings.

Koo says that:

Because the private sector was deleveraging, the government’s fiscal actions did not lead to crowding out, inflation, or skyrocketing interest rates.

Again, MMT would not express the situation in this way. The private sector may not have been deleveraging but still wanting to save and the fiscal intervention would not have caused any inflation.

The lack of any inflationary pressure relates to the relative state of nominal aggregate demand growth and the real capacity of the economy (supply-side) to absorb that spending via real output growth. When the non-government sector is increasing its saving rate (and aggregate demand growth falls) then fiscal policy has to fill the gap for output growth to remain stable.

If it “over-fills” the gap and thus runs nominal spending growth above the capacity of the real economy to absorb it then inflation will result. It has nothing to do, per se with the deleveraging of the private sector. The deleveraging is, however, motivated by the increased desire to save which is the ultimate culprit.

Further, there is no financial crowding out issue involved in government issuing debt.

It is clear that at any point in time, there are finite real resources available for production. New resources can be discovered, produced and the old stock spread better via education and productivity growth. The aim of production is to use these real resources to produce goods and services that people want either via private or public provision.

So by definition any sectoral claim (via spending) on the real resources reduces the availability for other users. There is always an opportunity cost involved in real terms when one component of spending increases relative to another.

However, the notion of opportunity cost relies on the assumption that all available resources are fully utilised.

Unless you subscribe to the extreme end of mainstream economics which espouses concepts such as 100 per cent crowding out via financial markets and/or Ricardian equivalence consumption effects, you will conclude that rising net public spending as percentage of GDP will add to aggregate demand and as long as the economy can produce more real goods and services in response, this increase in public demand will be met with increased public access to real goods and services.

If the economy is already at full capacity, then a rising public share of GDP must squeeze real usage by the non-government sector which might also drive inflation as the economy tries to siphon of the incompatible nominal demands on final real output.

However, the question is focusing on the concept of financial crowding out which is a centrepiece of mainstream macroeconomics textbooks. This concept has nothing to do with “real crowding out” of the type noted in the opening paragraphs.

The financial crowding out assertion is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention. At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking.

The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

At the heart of this erroneous hypothesis is a flawed viewed of financial markets. The so-called loanable funds market is constructed by the mainstream economists as serving to mediate saving and investment via interest rate variations.

This is pre-Keynesian thinking and was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

So saving (supply of funds) is conceived of as a positive function of the real interest rate because rising rates increase the opportunity cost of current consumption and thus encourage saving. Investment (demand for funds) declines with the interest rate because the costs of funds to invest in (houses, factories, equipment etc) rises.

Changes in the interest rate thus create continuous equilibrium such that aggregate demand always equals aggregate supply and the composition of final demand (between consumption and investment) changes as interest rates adjust.

According to this theory, if there is a rising budget deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending.

So allegedly, when the government borrows to “finance” its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment.

The mainstream economists conceive of this as the government reducing national saving (by running a budget deficit) and pushing up interest rates which damage private investment.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost self-evident truths. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

Further, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. But government spending by stimulating income also stimulates saving.

Additionally, credit-worthy private borrowers can usually access credit from the banking system. Banks lend independent of their reserve position so government debt issuance does not impede this liquidity creation.

Finally, Koo knows full well that the Bank of Japan controls short-term interest rates and can, if it wants to, control longer maturity rates. There was never a question that rates would skyrocket!

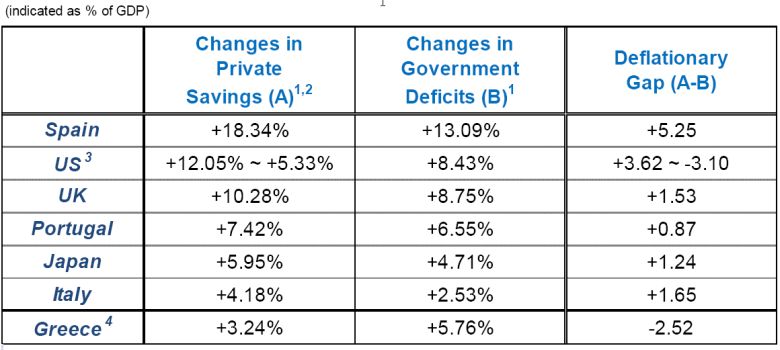

An interesting part of his testimony came when he compared private savings during the last two years and shows how they “have exceeded increases in government borrowings, which suggest that governments are not doing enough”. He offers this Table (his Exhibit 6) to demonstrate this point (you can read his notes to the Table in the testimony).

From this he concludes that:

Yet policymakers in many of these countries, spooked by what happened to Greece, have made strong pushes to cut budget deficits as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, the proponents of fiscal consolidation are only looking at increases in the deficit … while ignoring an even bigger increase in private sector savings … Removing government support in the midst of private sector deleveraging will repeat the Japanese mistake of premature fiscal consolidation in 1997 and 2001, which in both cases triggered a deflationary spiral and increased the deficit … In fact, Japan would have come out of its balance sheet recession much faster and at a significantly lower cost … if it did not implement austerity measures on those two occasions. The U.S. made the same mistake of premature fiscal consolidation in 1937, with equally devastating results.

This is a powerful statement and has been lost in the policy debate. When you have a collapse in private spending then public spending has to increase both in absolute terms and as a proportion of GDP to make up for that if you want output growth and incomes to be stable.

You might hate government spending so much that you are prepared to tolerate the mass unemployment and massive wealth losses that would accompany a zero discretionary fiscal response. But you should admit that bias rather than lying and trying to persuade the public that private spending will suddenly re – emerge from its slump and start driving output again.

It will not usually do this and when there is balance sheet correction going on it will definitely not do that. The fact is that the fiscal intervention has been too modest by a long way and that is why the US has 10 per cent odd unemployment and Europe is in a deep crisis.

The generational costs of not intervening with fiscal policy are also huge. When you lose your home because you can no longer pay the mortgate after losing your job, the wealth impact is huge and long – lasting.

The only point that Koo assumes in his analysis above is that the external situation doesn’t fill the gap (net exports improving). That is a very reasonable assumption given the widespread malaise in domestic economies but should be made explicit.

Koo also notes that:

There is actually no reason why a government should face financing problems during a balance sheet recession. This is because the amount of money it must borrow and spend in order to avert a deflationary spiral is exactly equal to the un – invested savings in the private sector (the $100 mentioned above) that is sitting somewhere in the financial system. With very few viable borrowers left in the private sector, fund managers in financial institutions should be more than happy to lend to the government, the last borrower standing.

Although talk of “bond market vigilantes” is often invoked by deficit hawks pushing for fiscal consolidation, the fact that the 10-year bond yield in the U.S. today is only 3 percent – an unthinkably low yield given a fiscal deficit of over ten percent of GDP – suggests that bond market participants are aware of the nature of balance sheet recessions.

I liked the “last borrower standing” terminology (and stole it for my title today). But overall MMT would not present the situation in this way.

A sovereign government will never face a “financing” problem because ultimately it can dispense with all the neo-liberal flim-flam that gives the impression that it is issuing debt to spend and keep spending regardless.

Further, it just borrows what it spends anyway. It does not need “prior” saving to draw upon. The spending creates the funds that are drained via the debt-issuance.

But the point Koo makes is important in the sense that credit markets are so weak and bond yields though very low are better than nothing for those holding cash.

Finally, I liked Koo’s conclusion:

Although anyone can push for fiscal consolidation by advocating higher taxes and lower spending, whether such efforts actually succeed in reducing the budget deficit is another matter entirely. When the private sector is both willing and able to borrow money, fiscal consolidation efforts by the government will result in a smaller deficit and higher growth as resources are released to the more efficient private sector. But once every several decades, when the financial health of the private sector is impaired and in need of treatment, a premature withdrawal of that treatment will both increase the deficit and weaken the economy …

Yes, and I would be calling for notable deficit terrorists to sign contracts that they will give up their incomes and wealth when their predictions about austerity fail to materialise and economies head the way that Koo is describing here.

The fact is that there is a current need for even greater fiscal stimulus in every country I can think off. There is no problem with increasing budget deficits as a percent of GDP or increasing the debt ratio. I would not issue any more debt but it doesn’t matter if the government does.

There is no solvency issue at stake for sovereign governments.

There is no risk of inflation at present.

There are greatest gains to be made in reducing unemployment

Conclusion

Policy design would be much better if there was an understanding of what the problems were. That understanding is missing at present and the actions of the deficit terrorists work to further obscure the message from the public.

That is enough for today!

Very telling.

There has been another news making headlines in the blogosphere recently. That is the extraordinary cash balances and profits of corporate sector. Looks like people seriously do not understand that budget deficits do not evaporate from this planet and go somewhere on this planet. It was already Minsky who showed that in any recession budget deficits first go to households as direct recipients of automatic stabilizers and later as corporate sector starts its adjustment of investment plans budget deficits start to increasingly flow into their p&l statements. And as Koo notes this profits (cash) is happy making something in government bonds than nothing (or rather giving this income to banks) in cash. Partly this money is also chasing risky assets and here we get to rising stock market with bleeding private sector.

Bill

Many, thanks for this blog.

I found this on the Bank of England site re quantitative easing.

There are three main lessons to be learned from the Japanese experience in regard to quantitative easing. First, policy needs to act early and decisively. The Bank of Japan cut its policy rate to 0.5% in September 1995, but it did not start quantitative easing until March 2001. In the United Kingdom, quantitative easing started in March, the same month as the MPC cut Bank Rate to 0.5%.

Second, policy should not focus on a single transmission channel. The Bank of Japan sought to increase the banking sector’s money holdings by buying assets principally from the banks. This meant that there was no direct effect of the Bank of Japan’s actions on broad money – the money holdings of the non-bank private sector. So the Bank of Japan, in order to have an effect on broad money, was entirely reliant on the banks reacting to the extra reserves by expanding their lending. But the banks simply hoarded the reserves and did not expand lending. The Bank of England has taken a different approach, which aims to have a direct effect on broad money, and works through a wider range of channels to stimulate spending. In particular, it has focused on purchasing assets from the non-bank private sector in order to increase directly the money holdings of private individuals and companies who are more likely to spend this extra money. Of course this may then be reinforced if the banks choose to expand lending as well.

Third, the Bank of Japan bought only government debt until mid-2002. Though small in terms of the quantity of actual purchases, the Bank of England’s willingness to purchase corporate assets is an important part of our strategy. That willingness to purchase private sector assets has helped to ease credit conditions directly for those firms using these markets to raise funds.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetarypolicy/qe/askqa.htm

Quoted today {on Bloomberg}. QE ‘last year’ was £200b..

What do you mean by the statement, “I would not issue any more debt but it doesn’t matter if the government does.”? That you wouldn’t make any personal loans?

For a government to spend money it doesn’t collect in taxes, must it then not borrow? What happens when the borrowing of the three largest economies exceeds global savings? This is the direction where the economies of the US, the European Union, and Japan are headed.

I don’t see how you can say national debt doesn’t matter.

Dear Informed Consent

Please go back into my archive and read the blogs under Debriefing 101

For example – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

best wishes

bill

Bill: Why do you have ANY kind words to say about borrowing, given that Abba Lerner favoured straightforward money printing rather than government borrowing? Government borrowing is one HUGE, UNMITTIGATED, POINTLESS FARCE.

Will someone please tell me what the advantage of government borrowing is as against the much simpler alternative, namely to have government just print money and spend it? And if anyone mentions the word “inflation”, I’ll come down on them like a ton of bricks!

Another really great post!

It is astonishing how few people can see the difference between fiat money and commodity money.

The difference has the effect of inverting the relationship between government borrowing and interest rates and inverting the resultant relationships of mercantilist economies.

The failure to understand it has the Western economies on the brink of a neo-liberal Great Leap Forward that can do for our capital base everything China’s leap did for its intelligencia!

Bill, you said:

“But you should admit that bias rather than lying and trying to persuade the public that private spending will suddenly re – emerge from its slump and start driving output again”

The US gave a tax rebate in 2 Qtr of 2008 and gdp jumped. I think you are making a wrong assumption (based on that evidence) that private sector spending will not re-emerge if taxes are cut for workers (a payroll tax cut). Yes, some will go to balance sheet repair, but that needs to happen anyway. Current Govt spending is going directly to buldging corporate cash reserves and doing very little economic good. And as I have said before, I am a firm MMT follower and JG believer, but I think the fix for the current mess goes beyond that.

Ralph,

Digression:

If you mean literally printing money, it is inefficient. The government can get currency notes from the central bank by either going overdraft (if it has the facility) or by a reduction of its balance of its central bank account. The holder of the currency notes will deposit it in a bank with the latter compensating him/her by crediting his/her account. The bank exchanges it at the central bank and is compensated either by a reduction of the central banks’ claim on the bank or by an increase in settlement balances.

The National Central Banks in the Euro Zone are allowed to print as much currency notes as they want 🙂

In India, a part of the government expenditures happens through currency notes. The government runs a rural employment scheme and most of the people working do not have a bank account.

Ramanan: Sorry, I should have been clearer on what I meant by “print money”. What I meant was, given insufficient AD, the government – central bank machine should just expand govt spending by writing out cheques drawn on the central bank, to pay for extra govt spending. As to government borrowing (Treasuries in the U.S.) just forget about them! They are bits of paper that serve no useful purpose.

John Wright Patman, Congressman and chairman of the Committee on Banking and Currency (1963-75) expressed much the same idea:

“When our Federal Government, that has the exclusive power to create money, creates that money and then goes into the open market and borrows it and pays interest for the use of its own money, it occurs to me that that is going too far. I have never yet had anyone who could, through the use of logic and reason, justify the Federal Government borrowing the use of its own money… The Constitution of the United States does not give the banks the power to create money. The Constitution says that Congress shall have the power to create money, but now, under our system, we will sell bonds to commercial banks and obtain credit from those banks. I believe the time will come when people will demand that this be changed. I believe the time will come in this country when they will actually blame you and me and everyone else connected with this Congress for sitting idly by and permitting such an idiotic system to continue.”

Bill,

thx for the assessment of Richard Koo. I read his ‘balance sheet recession’ and found it good, though his articulation of the stock – flow links was a little more primitive than it might have been. I’ve been meaning to open my copy of his new one for weeks, but time is short right now.

Bill:

Apparently what you are saying is falling in to deaf ears. The sky is falling for most nations if they dont become austere. 🙂 http://money.cnn.com/2010/08/05/news/economy/social_security_trustees_report/index.htm?hpt=T2

Deaf ears all right. The AFR has a major funds advisor today whipping up deficit hysteria and the idea of US default…hmmm….

Ralph, I guess the central idea behind borrowing is that banks get income from witch to pay their depositors interest. Im not fan of the practice either. :/

Ah, the Keynesian superstition again. Koo’s example above would only be true if a) the $100 of savings was held in the form of actual cash (the monetary base); and b) the U.S. was on a 1920s-style gold standard that prevented the Fed from simply increasing the size of the monetary base to replace the money (and demand) that had gone into the saver’s mattress. The only reason that demand is not recovering right now (irrespective of concerns about personal and corporate “balance sheets” and their “repair”) is that the Fed is neutering its own monetary policy by paying interest (at above-market rates) on bank reserves. If the Fed were to stop this insane “interest on reserves” policy, demand would return to normal within a week and the Fed would have to sell off about $1 trillion in assets to avoid an inflationary blast.

While it is true (by definition) that Demand is numerically equal to Consumer Spending plus Business Investment plus Government Spending plus Net Exports, this is *not* what demand *is*. Demand *is* the circulation and exchange of money (monetary base times velocity). The Fed is artificially suppressing velocity by paying interest on bank reserves. They need to stop doing this.

Physically, there is nothing wrong with the economy, and no benefit to low GDP and employment.

“The lack of any inflationary pressure relates to the relative state of nominal aggregate demand growth and the real capacity of the economy (supply-side) to absorb that spending via real output growth. When the non-government sector is increasing its saving rate (and aggregate demand growth falls) then fiscal policy has to fill the gap for output growth to remain stable.

If it “over-fills” the gap and thus runs nominal spending growth above the capacity of the real economy to absorb it then inflation will result.”

So how does the government gauge exactly what the capacity of the economy is? Obviously the unemployment rate is a guide, but it’s not always reliable.

For example many countries in South America (Venezuela for example) simultaneously have high unemployment and high inflation rates.

To put it another way, inflation can result from excessive government spending even when the economy is not at “full capacity” (ie 2% unemployment).

The reality is that there is far more to the productive capacity of a nation than simply the number of unemployed people (or to use the academic jargon, “underutilised resources”). In Australia, our productive capacity over the last few years has been restrained by the amount of skilled people available. There have not been a great many unemployed builders or accountants around for a number of years.

So how does a government “fill the gap” without pushing up wages in these constrained sectors? How does the government target the spending correctly? Because the Australian government has a truly woeful record on targetted spending. The home insulation scheme is the obvious example, which was a truly embarrassing debacle that people won’t forget in a hurry.

Well, here it is. Tony Abbott is now supporting the idea of a job guarantee:

http://www.smh.com.au/federal-election/the-leaders/abbott-declares-war-on-youth-dole-20100806-11oid.html

Great post. Enjoyed finding your blog.

I would add the caveat though that the reason this is all true is that people ultimately have faith in the stability of the US (and Japan) financial system. As suggested by other comments, some countries (Venezuela I saw) could not take this action because people will take their money elsewhere.

I would also add that a large contributor to the austerity argument is pride, in that “I am right and Obama is wrong.” For the record, Im not an Obama supporter, but I can leave that at the door when evaluating this issue. I wish more could do the same.

Koo says:

“In order to regain their financial health and credit ratings, households and businesses in the private sector are forced to repair their balance sheets by increasing savings or paying down debt, thus reducing aggregate demand.”

I’ve noticed this before from Koo, and I don’t see that it’s quite right.

Paying down debt is a balance sheet transaction that is operationally separate from the act of saving. The initial balance sheet entry from saving typically is a bank deposit, representing one’s pay check, for example. Having saved, one could just as easily leave the deposit as is, instead of using it to pay down debt. Either way, one has saved. The intention to pay down debt may well be an incentive for saving and a possible balance sheet outcome of saving, but it’s not an alternative to saving. At the macro level, a “balance sheet recession” due to debt liquidation doesn’t necessarily mean there is any less investment generated by gross saving, or any less net financial asset value generated by net saving from particular sectors. Paying down debt doesn’t “use up” macro saving anymore than does the accumulation of new gross financial assets. Saving and paying down debt are not alternatives. Paying down debt is a liability management option for saving, along with asset management options. Aggregate demand reduction results from the decision to save – not to adjust one’s balance sheet on the liability side (although such liability adjustment is an incentive to save). Investment gives rise to saving. Knock-on financial adjustment may be asset or liability oriented.

Then he says:

“… when the private sector de-leverages in spite of zero interest rates, the economy enters a deflationary spiral because, in the absence of people borrowing and spending money, the economy continuously loses demand equal to the sum of savings and net debt repayments.”

That’s the same error, as far as I’m concerned. The aggregate demand reduction comes from saving (and any paradox of thrift associated with it). I don’t see that you can double count saving and debt repayment and come to think properly about this. Again, the motivation to save may be influenced by the motivation to pay down debt – but the aggregate demand effect is a function of the saving, not the sum of saving and debt repayment. Debt repayment is simply a financial transaction subsequent to the act of saving, just like leaving your money in the bank or buying a stock with it is.

Koo’s got some of the macro accounting themes right, but he slips up at this level, I think.

Then Bill says:

“While I am not really enamoured by this representation of the banking system, the dynamic is accurate. The shrinkage in spending is the multiplier in action.”

That critique is sufficiently mild that it makes me question the correctness of my own analysis. Perhaps I am wrong, but I would be totally torching that section of Koo’s writing. My reading of it is that it is just completely wrong as a description of comparative dynamics, and totally inconsistent with MMT type comprehension of the banking system. Whether one ends up with an additional financial asset or a reduced liability is irrelevant to the substance of having saved and irrelevant to the substance of how that act of saving has impacted aggregate demand. Again, the motivation to pay down debt may affect the motivation to save, but the act of paying down debt versus the act of increasing a financial asset has nothing to do with the dynamic of saving itself, nor with the actual effect on aggregate demand. I suppose we could look at it as the act of not paying down debt leaves open the option to spend, but then we’re not talking about saving at all, are we? Koo’s comparison of the two dynamics is also completely inconsistent with the idea that investment brings forth saving. The financial adjustments around saving are not a factor in that idea.

I dare say Koo is closer implicitly to a monetarist view in the way he describes things, given the effect of balance sheet deleveraging on money supply, other things equal. Notwithstanding major problems with the monetarist story, I might relate to that sort of connection more readily than the way in which he actually describes things.

JKH, I’m struggling to get your point. Isn’t Koo just saying that households are not spending all of their income? The effect of this is either (1) those households which have no debt are saving or (2) those households which have debt are reducing it.

I can’t see where he’s suggesting that there is a double effect, once when the saving occurs, then again when the debt is repaid. I don’t think many people would actually do this. Why would anyone who has a mortgage, also have a savings account? They would be foregoing or paying a spread (depending on their net position) of at least 100bp you would think.

Cheers.

Also, JKH, I can understand your confusion regarding Bill’s qualified support of Koo’s analysis. From first glance Koo’s ideas seem to be a standard debt-deflation story.

Debt-deflation theory seems to be far more concerned with the level of household/business sector debt (ie non-bank private sector) than things like net private sector (including bank and non-bank) financial assets, which MMT more often talks about.

This is not to say that debt-deflation and MMT are necessarily inconsistent, my understanding is that they attribute the cause of recession/depression to different (but not mutually exclusive) causes. What is the terminology Bill uses? MMT focuses on the “vertical” transactions while debt-deflation focused on the “horizontal” transactions.

Gamma,

What Koo actually says is:

“The economy continuously loses demand equal to the sum of savings and net debt repayments.”

I’m not sure what he means, but what he says is wrong. Saving is an income event (income without expenditure). Debt repayment is one financial outlet for saving. It is a balance sheet event. If people pull back on aggregate demand by saving, they don’t pull back a second time as a result of using their saving for debt repayment – no more than they do by leaving their saving in the form of a bank deposit. So I don’t know what he means by “the sum” of these two as some sort of expression of total demand loss. It simply doesn’t make sense. Debt repayment is merely a financial transformation of what has already been saved.

Repeating myself from above, I would say instead that the intention to repay debt is a motivation to save, just as is the intention to build up a retirement nest egg of financial assets. But that’s not how Koo says whatever it is he is saying. Again, it makes zero sense to me.

Regarding your statement:

“The effect of this is either (1) those households which have no debt are saving or (2) those households which have debt are reducing it.”

Households are saving in both (1) and (2). The first group saves in the form of additional financial assets; the second group saves in the form of reduced liabilities. Both types of balance sheet stock adjustments are facilitated by the same type of income saving flow.

“Why would anyone who has a mortgage, also have a savings account?”

Perhaps some people wouldn’t; perhaps some would. But we know for sure that not everybody has zero financial assets, whether savings accounts, bonds, or stocks. So the world includes those who have financial assets, those who have liabilities, and those who have both.

I see no problem in reconciling debt deflation or balance sheet recession with an MMT understanding of the monetary system. Both versions of the problem result in aggregate demand shortfall, and MMT would prescribe fiscal action to supply net financial assets in response.

My interpretation of Koo’s statement is that he is splitting “saving” (income – expenditure) into two components, one being addition to “savings” (increase in financial assets) and the other being debt repayment (reduction in financial liabilities). So Koo’s demand leakage via saving is equal to “increase in savings” + debt repayment.

I think he’s just using the word “savings” more informally, but I could be hopelessly off track and confused. Wouldn’t be the first time.

ParadigmShift, you’re correct. It’s just semantics. He’s using the word savings in the commonly understood meaning of “increasing bank balances”.

He is not suggesting double-counting, once for “increasing bank balances” and then again when the same money is used to reduce debt. I guess you could take this view, but you would have to include the effect of decreasing the bank balances that are used to pay down the debt, which gives the same result.

Paradigm Shift, Gamma,

You may be quite right. Perhaps by “savings” he simply means cumulative saving to acquire assets. If so, it’s very sloppy. In any case, I’m not certain that’s what he means.

In any event, a specialist in the stylization of “balance sheet recessions” should be more careful about how they use accounting and economics language. “Saving” is an income flow that is not spent. “Savings” is cumulative saving. Either mode can be positive or negative for a given income statement and/or balance sheet. Neither connotes a specific balance sheet condition per se, except for the directionality of equity or net worth.

Beyond that, the gross balance sheet condition is a consequence of how saving and savings are utilized. The alternative to using saving to pay down liabilities (i.e. debt) is to use saving to maintain or increase assets (depending on how you look at the accounting timing for the increase in equity that is associated with saving).

Koo says:

“More importantly, when the private sector de-leverages in spite of zero interest rates, the economy enters a deflationary spiral because, in the absence of people borrowing and spending money, the economy continuously loses demand equal to the sum of savings and net debt repayments.”

The only possible coherent interpretation of this is that the economy loses demand equal to saving per se. Since “the absence of people borrowing and spending money” is assumed, the implication is that the gross balance sheet result of saving is some combination of an increase in gross assets and/or a reduction in liabilities (i.e. debt). In any event, the interpretation that saving per se represents a continuous loss in demand is very extreme. Paying down debt and balance sheet recessions are a matter of degree, not extreme points cast in stone.

In his household example, Koo says “In the world where the private sector is minimizing debt, however, there will be no borrowers for the saved $100 even with zero interest rates, leaving the economy with only $900 of expenditure.”

I think this is a dreadful way to describe the balance sheet dynamic. The idea that “there will be no borrowers for the saved $ 100” is simply wrong in its causality, and I would have thought Bill would have jumped all over it from an MMT perspective. The only possible way this could be correct is that an economic unit that saves in terms of bank deposits, without paying down debt, is more likely to increase or maintain its aggregate demand contribution in the subsequent period, compared to the unit that pays down its debt. As noted above, nothing really wrong with that idea, although it seems to me to be close to a monetarist view, based on money supply effect. (Money supply contraction is consistent with balance sheet recession.)

The idea that a balance sheet recession is a particular drag on aggregate demand is quite sound. But the way to look it from a balance sheet perspective is that the desire to pay down debt is a motivation to save. Any motivation to save becomes a potential contributor to the paradox of thrift. To the degree that balance sheets are severely impaired, the inducement to pay down debt is therefore strengthened and the motivation to save is increased. Accordingly, the drag on aggregate demand is heightened. It’s really pretty simple, without the need for torturous abuse of balance sheet accounting terminology and logic.

The way that I interpret Koo is that debt repayment in a deflationary setting extinguishes the demand potential that liquid savings represents.

Savings is a way to temporarily maintain a liquidity buffer for anticipated future expenditure – it removes demand, but remains as potential demand. As debt is repaid, that potential future demand is gone, unless offset by increased borrowing and spending (no, savings does not serve as the source of borrowed funds, but the relationship between the two is important).

From a balance sheet/stock perspective, savings and debt reduction are the same. From a spending flow view, there are different dynamics.

Compounding this is that banks are not lending (and/or borrowers are not borrowing) hence a deflationary spiral sets in.

So balance sheet repair is to address risk reduction and not to facilitate increased spending capacity. Kind of like the spending multiplier in reverse – call it the debt reduction divisor.

This is a reason why spending multipliers get wonky in deflationary settings and don’t have the same strength as in a standard recession. Another reason why government spending and deficits should be even higher.

JKH, since you are posting here at the moment, an off topic question ….

if government issued nominal risk free liquid bonds are equivalent to money (a position MMT takes and with which I belive you concur), then presumably their issuence has been causing inflation. Presumably also at the point when they became risk free (after the gold window was closed) there must have been an inflationary impact as the market began to ‘monetise’ them.

If government bonds are money substitutes then what is the transmission mechanism from there to prices?

As a monetary reformer, I find it ironic that Ralph has offered the very considered and ultimately pertinent opinion of the esteemed former Chair of the House Banking and CURRENCY Committee from down in Patman Switch, Texas, stating that the government is FULLY capable of creating ALL of the nation’s money to do EVERYTHING that MMTers say they want to do, and the replies for the most part ignore Ralph’s comment, Mr. Patman’s statement and this reality.

Real, essential monetary reform is the enabler for accomplishing all of the noble goals of MMT, doing so based on two quintessential realities: that of monetary sovereignty and the public purpose use of the monetary system for achieving the fullest possible employment of all citizens.

And you don’t need to convince people that the government neither has nor doesn’t have any money.

Just saying.

scepticus,

I think MMT would say that inflation is caused by aggregate demand pushing up against real resource constraints. These are the prerequisites to inflation, not the stock of money or the stock of government bonds per se. In that sense, MMT might then say that neither money nor bonds are the direct cause of inflation. And as far as that goes, MMT might then also say that money is no more inflationary than bonds, because bonds are easily posted as collateral for money credit.

Its easier to see in the circular flow of income approach. In an accounting period, households receive wages for their labour and consume a part of the wages. Whatever is saved is allocated into their bank deposits and assets such as bonds. The consumption is proportional to wages not related to the bank deposits or bonds. Whatever is not consumed is allocated and added to their previously existing holdings of deposits and bonds. So its more appropriate to say that households “consume out of wages” instead of “consuming out of bank deposits.”

Bill,

I understand why you want to present your argument for deficit financing in an accounting framework. But I think it has serious defects as a way of introducing these ideas to someone who is skeptical (ie nearly everyone, because eveyone knows that govt can’t just print money). Firstly, except at an elementary level most people don’t naturally think in accounting terms. And it’s exactly when you try putting some rigour into your argument that most people are most alienated. This I think helps explain the view that I’ve seen expressed a few times on your blog, that there’s something … missing. But just as important is that the accounting structure says nothing about the physical causality of what’s going on. Accountants don’t make anything, they just add up the numbers for those that do. So for someone accustomed to thinking in a wide range of disciplines that’s what’s missing – causal relationships.

My suggestion is that you can establish in principle the need for deficit financing using the approach I’ll outline below reserving the accounting structure for the next stage of refining ideas for those who have been able to see that there could well be an important point.

I’ve been following Steve Keen’s work for quite a while and you will see his influence. For simplicity this is presented as a single firm economy but can be generalised to an n-firm economy. BTW, I doubt very much that there is anything new in what I’m saying but I haven’t seen it anywhere in this simple algebraic form.

I consider the “real (closed) economy” to be described by the following three equations

PQ=kF (1)

LW = (1-s)kF+J (2)

Q=aL (3)

The firm sells Q units per unit time at price P ($ per unit). The firm has net assets F ($) and it’s sales amount to a return k as a fraction of net assets per unit time. There are L workers each receiving the wage W, $ per unit time. The firm retains fraction s of the return on net assets kF and distributes the rest, (1-s)kF, to workers as wages. The additiona term J in (2) is an injection of “money” ($ per unit term) from an external source (such as govt, maybe banks) net of taxes (ie tax is taken out of the economy at the rate -T and returned at the rate T; J is additional). And (3) is just the definition of productivity, a, units per worker.

There are at least two ways of taking the next step which will make more or less sense to different people depending on how they see the real economy:

A: I think this is the natural way for workers and owners of firms to think. Workers choose to spend the fraction v of their wages on buying the firms output

vLW = PQ (4)

Some simple algebra using (1), (2) and (4) gives

J = (1-v)LW + skF (5)

So for the economy to work as descibed by (1), (2) and (4) the injection J from external sources must equal the sum of workers savings, (1-v)LW and retained earnings by firms, skF. Any less than this and either workers are unable to save as much as they would wish or firms cannot have the retained earnings they wish, or both.

B: The natural way for proponents of MMT (and Warren Mosler) to think. The system has leakages due to workers savings (1-v)LW and retained earnings skF so this need to be made up. So (5) must be the case and a little algebra gives (4).

So in (5) those wanting a balanced budget J=0 at all times should expect in practice either

(i) if (1-v) and s are both not zero, then LW=kF=0

or

(ii) if LW and kF are both not zero, the (1-v)=s=0

Neither a good outcome.

If J is not zero and (4) holds

W/P = Q/Lv

= a/v (6)

using Q=aL. (6) shows a stable economy with real wages dependent on workers productivity and savings.

Alternatively, from a policy perspective it might be supposed that (6) is the objective and there is then the question of how to achieve this. The answer can be found by introducing (6) into the basic equations (1)-(3) and with a little algebra deriving (5).

If s>0 the rate of change of F is skF so net assets are growing with reasonable assumptions about k, and it is easy to see that LW and PQ are also growing. If so, there is growth without inflation.

The same equations work with v>1 (ie credit available for workers) and s<0 (debt financing for firms). The correponding terms in (6) are negative. So if the banking sector steps in the govt role is reduced and may actually involve withdrawals. But if the govt withdrawals actually occur the reason is to maintain (4) not "pay the debt" incurred over periods of govt injection.

There is no need to explicily model the financial sector, which can do what it wants. Provided the govt acts according to (5) (injections into the real economy when the financial sector fails, withdrawals when it is overheated) stable growth can be maintained in the real economy whatever the financial sector does.

Ramanan,

Right. Money stock is the tail of the inflation dog.

JKH+ramanan. thanks for those answers. Are you saying then that if aggregate demand exceeds resource constraints or if consumption as a proportion of income goes up then bond holdings will acquire a velocity greater than they currently have. Currently government bonds (at least in the UK) have an annual turnover/velocity of about 7 or 8, which is well in excess of MZM velocity.

If the stock of money (the tail) matters most when the economy is running at full capacity then is it correct to fear that in a full capacity event (such as for example savings rates declining as the boomer bulge passes into full time retirement) that bonds may suddenly compete with bank deposits/base money as a medium of common exchange? That would seem to hold out a potentially worse inflationary impact in this full capacity scenrio than one would infer just looking at base money.

scepticus,

I’m not clear on the importance in general of bond turnover or “velocity”. In large part I would think it reflects portfolio management asset allocation and trading decisions, rather than aggregate demand propulsion activity.

If aggregate demand presses up against real resource constraints so that inflation is a threat, then both monetary policy (interest rates) and fiscal policy (deficit reduction) are available. I think the MMT preferred route for this is fiscal policy.

I’m not sure how MMT views the stock of money and bonds when real resource capacity is at limit and inflation is a threat. If the money stock becomes an inflation risk then it stands to reason that the bond stock does as well, due to the liquidity properties of bonds. But I see both money and bonds as more of a catalyst to the underlying inflation threat, which is the constraint on available real resources. MMT would tackle the underlying inflation threat primarily through fiscal policy, as I understand it, with money and bond adjustments coming out in the wash.

scepticus,

It seems to me that an important although somewhat indirect message of MMT is how to be correct in identifying those particular circumstances under which fiscal tightening is called for, and if so how to get the timing right in taking such action. Understanding the monetary system is a critical input to the analysis. On that basis, neoclassical analysis is almost always biased toward premature fiscal tightening, based on faulty monetary analysis and a faulty understanding of the nature of the inflation transmission process.

JKH I agree with the point about neoclassical economics and pointless tightening.

My thinking was more along the lines of whether the market has already performed a de-facto monetisation of government bonds over the last 40 years – certainly gilt turnover has increased very significantly since the gold window was closed. I also understand that government bonds are an essential part of the scaffolding around which the shadow banking sector was built.

While they may or may not be the tail of the inflation dog monetary stocks do matter as does their velocity so if nominal liquid bonds are money or became money then it must have had significant impacts which are never discussed or analyse or ‘counted’. That is why I wonder whether government bonds acting as money are the ‘financial dark matter’ that neo-classic economics ignores.

I found some papers by a fed economist: “Societal benefits of illiquid bonds’ by Narayana R. Kocherlakota. Seems that at least some in the fed also recognise the equivalence of liquid nominal bonds and money. But no word from this guy on the real world implications of that for our existing economy .

Scepticus,

There is a relation between money and prices but the causality is the opposite. The reason Monetarism became popular in the 70s is because prices increased and the money supply increased as well.

Neoclassicals got the causalities wrong. Before the Monetarist experiments started, central banks were targeting interest rates only. However, because wages increased so much – talking of the UK experience – ‘money supply’ also increased because producers increased bank loans to pay for wages. The Monetarists ‘realized’ that there is a connection and forced central bankers to control the money supply. The central banks agreed and started targeting the money supply. However, in practice, they were just targeting interest rates but with a “central bank reaction function” which had money in it. This lead to a huge increase in rates, causing a recession.

They couldn’t realize the causality however – they could have prevented wages from increasing faster than productivity growth. Instead they did something really bad. Central banks however abandoned targeting money supply later (mid 80s?) – but the myths still remain till today!

However, note that increases in the money stock can’t cause inflation. If it is the case that wages grow at the rate equal to rate of productivity change, one has low inflation. Instead, faster money supply growth leads to an increase in employment. In fact, the causality is again the opposite. Higher demand increases bank borrowing and hence higher money supply and higher wage bill as opposed to higher wage rate and this increases employment instead of increasing prices. (Assuming wage rates don’t grow faster than productivity growth rates)

ramanan, two points. Firstly, I suggest that the mechanism outlined in your post above won’t quite work that way when labour markets start to tighten as a result of an increase in the dependancy ratio which is an inevitable outcome of the boomer bulge and more generiaclly the demographic transition.

Secondly, I note a secular increase in velocity of money from about 1975 onwards:

http://www.marketoracle.co.uk/images/2008/velocity-of-money-april08-image005_3.jpg

Does MMT have an explaination for the increase since 1975 and the more recent decline? I feel this is connected to the issue of liquid nominal bonds but I’d like to hear the MMT version.

Dear Bill,

RE: LT RATES AND PUBLIC POLICY

I thought that some time ago we agreed in comment exchanges that the only way to control LT public debt rates was for the Treasury and the CB to coordinate policy so that the treasury will stop issuing bonds and the CB will stand ready to purchase all available public bonds in the secondary markets. However, how is public policy going to control the spread between LT public and private debt?

There are only two possible scenarios that involve regime switch. One, is for the CB to stand ready to buy all available private debt in secondary markets assuming all is securitized and the second is for the state to socialize the financial sector. The first is an impropable scenario with a high securitization cost, immense liquidity and a huge CB balance sheet and zero ST rates.

The second scenario is more optimal as socialized financial institutions will offer loans and finance private capital formation while interest payments will be a means of taxation that allows society to share a portion of capital returns. As long as fiscal policy stands ready to cover any demand shortfall, systemic risk will be limited and as long as the state bank commercial portfolio is representative of the private sector economy, idiosyncratic risk will be diversified away. Thus with social risk limited, the interest rate offered will be equal to the zero ST rate plus some administrative cost premium. Furthermore, credit will be extended to credit worthy business plans to employ resources net of any community projects of sustainable social purpose financed by public spending. Taxation will then exist and act only as a penalty against excessive private economic behavior and waste, reallocating revenues towards those damaged (externalities), capturing and eliminating any economic rents yielded by this behavior. This policy can be as optimum as it can be.

djc,

Equation (1) and (2) need more explaining. How (J) affects labor income outside production? (1) and (3) become a price equation? How is (v) the spending propensity out of labor income affects the real wage in a behavioral hupothesis? What are the reasonable assumtions about k and how (F) grows? Your criticism of MMT regarding causal behavior is shared by me but it seems that you fall into similar circular thinking. I sympathise with your effort and probably you can explain the behavior behind your equations or “identities”. I have developed a more elaborate mathematical framework regarding macro relations without neoclassical behavior and I understand the difficulties involved.

Panayotis,

I’m not trying to develop a predictive model of a real economy. The model says nothing about how the individual values of P, Q, v etc (BTW, I should mention that all quantities will in general be functions of time) come about, or what determines them. So if workers spend the fraction v of their wages that’s just because for whatever reason they have decided to do that; and so on for other variables.

The approach I’m taking is to ask what would you do if you were in charge of an economy with the particular set of quantities that currently exist. So our policicians are currently competing with each other to acheive a budget surplus, which I take to be J=0 in the model. Does this make sense? Presumably they believe that this can provide a stable economy, with stable real wages and some growth. My conclusion is that J=0 is not likely to do this, instead J needs to be at a rate equal to the sum of worker’s savings and retained earnings. As I understand it, this is the MMT conclusion also. So I’m not disagreeing with MMT, I’m saying here’s another way to reach that conclusion. And since it includes everyday things like prices and wages it might be that some people will see the point when it is expressed this way rather than in an accounting context.

On your detailed points: Looking at the real economy as a consumer you see goods (or services) being sold at the rate Q (items per unit time) at price P ($ per item); as an investor you can look at share prices (ignoring the difference between maket value and net assets for now) and P/E ratios (approximately the inverse of k). So (1) says these are numerically the same. But at the same time you see workers spending their wages to buy these goods, and the source of these wages is the same firms as produce the goods. So (2) expresses total wages as the fraction of their earnings that firms pass on to wages. Without J in (2) – or the equivalent somewhere else – it is easy to see that this can’t work, because unless firms pass on all their earnings as wages workers don’t have enough money to buy the goods they have produced (and it is worse if workers wish to save some of their wages rather than spend it all). So somehow there needs to be an extra quantity J to make up the difference: some combination of fiat money, credit from banks, govt spending etc. But specifically this needs to go into the real economy, not the financial sector. Having seen the need for some nonzero J the actual magnitude needed is then found after assuming the rate of spending by workers is vLW, which is set the equal PQ.

Q=aL (3) is the used to show that under these conditions the real wage is “stable”; specifically it doesn’t deteriorate because of the injection of fiat money (provided this is at the correct rate).

A reasonable k just means that firms are run by competent people who know how to make a profit rather than a loss (k would also reflect the debt position of a firm – and in recent times could have changed dramatically because of this – but as k does not appear in the result required there is no need to specifically model this). As for labour outside production, I’m treating everyone as a worker who produces some item (or service) that someone else will pay money for. It looks a bit silly as a one-firm economy but it does generalise to n firms.

The other key thing is the shadowy presence of a financial sector whose only task is to contribute to the injections into the real economy. Their derivatives tradings are all between themselves and of no interest to the rest of us.

djc: Very nice discussion. In my opinion, MMT’s level of analysis is the appropriate one for macroeconomic analysis of a monetary system (I’ll get back to this), but I agree with you that exploring the real-economy aspects “underneath” this level of analysis also offers many insights.

Regarding your conclusion “J needs to be at a rate equal to the sum of worker’s savings and retained earnings”, I haven’t seen the point arrived at algebraically in quite the same way, but Kalecki’s identity for aggregate profit, which he arrives at from a model of the real economy, leads to the same conclusion. In a closed economy, P = Cp + I + BD – Sw, where P is aggregate profit, Cp is expenditure out of profit, I is gross private investment, BD is the budget deficit and Sw is saving out of wages. Rearranging, BD + I = (P – Cp) + Sw = Capitalists’ Retained Earnings + Workers’ Saving. The causation for Kalecki runs from injections to leakages, so we could rewrite this G + I = (P – Cp) + Sw + T, where G is government expenditure and T is taxation. In Kaleckian terms, the government and capitalists can choose what they spend in the current period, but not what they earn (leakages are endogenous).