I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

On writing fiction

I have been writing a fiction novel lately in my spare time (which is when I don’t sleep)! It is about the usual themes – individual struggle, tragedy and perhaps realisation. I haven’t yet conceived how it is going to end yet but it will either be very grim or full of splendour. Black and White I am! The interesting part of the exercise is trying to define one’s style separately from one’s academic style. I read a biography of Jack Kerouac recently and it talked about how he obsessed about trying to develop a unique style but kept falling back to be like one or another of the great authors of the day. It was only once he typed a lot that he started to find his own distinct identity as a writer. For me, the blog helps develop alternative ways of writing outside the terse cloistered world of technical economics. Anyway, I didn’t write much fiction today (yet) but I sure did read a lot of it.

The New York Times carried an Op-Ed article – Easy Money, Hard Truths – on May 26, 2010 written by a hedge fund president, one David Einhorn.

It was not just the poor economics that was on display but also a mis-use of statistics to try to reinforce the poor economics that was notable.

Einhorn asks his fellow US citizens – “(a)re you worried that we are passing our debt on to future generations?” Answer: “Well, you need not worry.” Why? Because the:

… the government response to the recession has created budgetary stress sufficient to bring about the crisis much sooner. Our generation – not our grandchildren’s – will have to deal with the consequences.

He claims (that the Bank for International Settlements) has estimated “the United States’ structural deficit – the amount of our deficit adjusted for the economic cycle – has increased from 3.1 percent of gross domestic product in 2007 to 9.2 percent in 2010”.

I have written cautionary blogs about structural deficit measurement before – for example, Structural deficits – the great con job!. Also in the context of today’s blog – this one is helpful – Another economics department to close.

The basic point is that, given the way they are constructed, the measure of full capacity is always biased towards higher rates of labour underutilisation than would be consistent with full employment.

As a consequence, if the structural deficit was estimated to be zero (that is, a balanced structural budget outcome), then in fact, the non-cyclical or discretionary component of fiscal policy (that is, the structural deficit) would be contractionary by some percent – perhaps even up to 3 to 4 per cent of GDP). The common way of producing these estimates always suggests the budget outcome is more expansionary than it actually is.

And of-course, this is very convenient if you want to run the neo-liberal line against fiscal activism. The bigger the deficit the easier the case is for the deficit terrorists to ring the alarm bells and cause unease among an ill-informed public.

First, the actual ratio doesn’t matter much at all because a sovereign government like that in the US is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. The ratio just reflects the state of private spending and decisions taken by government to support private saving and maintain output levels. In general, if unemployment is high, the deficit ratio is too low. So whatever the ratio is you should only consider it in relation to the state of the real economy, particularly the labour market.

Will any citizens actually feel the difference between a deficit ratio of 3.1 per cent or 9.2 per cent? Not if they keep their jobs. Some will also enjoy expanded income flow as a result of the increased wealth (public debt and other financial assets) that they have accumulated courtesy of the income flows supported by the expanding deficits.

Which reminded me of this national debt counter (picture that follows) that is on the front page of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation WWW site. Would some reader living in Washington D.C. ring the PGPF up and tell them that the title the title of their counter is wrong. Someone must have made a typographical error when compiling the graphic. What they are showing is the real wealth in the form of public bonds held by non-government sector although I am sure not every American holds in excess of $200,000 in public bonds wealth.

Second, if you are going to quote these sorts of ratios then it is better not to select dated estimates or estimates that are obviously higher than other publicly available estimates (unless you can argue why the higher estimates are superior). Remember structural deficit estimates are typically already biased. Higher deficit estimates usually are more biased.

The BIS actually doesn’t publish decompositions of budget outcomes. But the research he is referring to is the March 2010 paper written by some BIS researchers – The future of public debt: prospects and implications – which I discussed in this blog – Another economics department to close. In that blog I made the recommendation to the BIS that they would serve humanity better by closing this (non)-research department within their organisation down.

Einhorn also selectively quotes the BIS paper’s estimates (from their Table 1) leaving out the fact that by 2011 the ratio has dropped to 8.2 per cent. The BIS paper which Einhorn uses relies on IMF and OECD estimates. They are notoriously more biased than other biased methodologies. And just on Einhorn’s doorstep is the US Congressional Budget Office, which produces monthly estimates of the structural and cyclical US deficits. These are much more timely than anything the OECD or the IMF has published and are more modest. That is, the bias is lower.

Moreover, the CBO express the budget deficit in terms of potential GDP rather than actual GDP. So the denominator has much of the cycle strippped out of it and the measure better shows what is happening to fiscal policy. They say “(p)otential GDP is the quantity of output that corresponds to a high rate of use of labor and capital.” High rate of use does not equal full employment and that is where the bias creeps in.

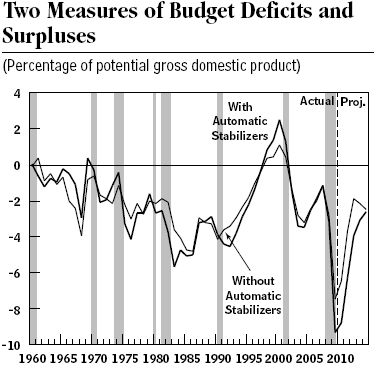

In the latest CBO publication for May – The Effects of Automatic Stabilizers on the Federal Budget, the CBO show that the deficit ratio was 1.2 per cent in 2007, rose to 7.5 per cent in 2009, and is predicted to drop to 6.5 per cent for 2010. By 2012, they estimate it will back to 1.9 per cent. It was last below 2 per cent in 2002.

The following graph is taken from their Figure 1. I am sure if I was to provide a comparison to the ill-informed public of the CBO estimates and the Einhorm representation of the data, the former would console them while the latter would agitate them. So even within the flawed logic of the whole exercise Einhorn chooses extremes to sensationalise.

Einhorn then says:

This does not take into account the very large liabilities the government has taken on by socializing losses in the housing market. We have not seen the bills for bailing out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and even more so the Federal Housing Administration, which is issuing government-guaranteed loans to non-creditworthy borrowers on terms easier than anything offered during the housing bubble.

This is another furphy. I don’t particularly support socialising private sector losses and allowing the private managers to keep their “private sector” salaries and bonuses and control of the assets. I think the US government should have turned all the institutions they offered bailouts to into public enterprises and refocused their strategic plans to advancing public purpose. Although it is hard to see anything remotely productive that Goldman Sachs, who were saved by a bailout, could do.

But in the spirit of the fact that governments do socialise private losses, here is a little scenario to get our thoughts focused. It is actually a preferred solution to say the housing crash.

Imagine that there is a housing estate comprising perhaps 1000 houses, each with a nice garden and lots of trees. Parents and their children live in this community and the usual rhythms of life occur. All the houses are being purchased by their owners on mortgage contracts from their local privately-owned bank. At some point, a major economic downturn hits and many people in the estate lose their jobs and find they can no longer meet their mortgage payments and are forced to default.

The bank is now faced with a massive loss which goes well beyond its capital. It is thus insolvent and on the brink of collapse. The government fears that if the bank crashes, it will lead to runs on other banks as depositors fear they will lose their cash. Accordingly, the government takes over all the bad mortgage debts by transferring the accounts from the private bank to the public accounts. Some keyboard operator makes the book entries to accomplish the transaction and lawyers do the contract work.

The government then, as a matter of social purpose, decides it is not productive for the houses to lie idle and that families should remain in their homes. They offer the families are new deal. The families can pay market rents to the government for five years and stay in the houses they were buying. Some families will receive rental subsidies in the meantime while they are unemployed.

After five years, the government will offer the occupant (former owner) first right to purchase the house at the current market rates. If they choose to do that all rental payments in the five year period will be retrospectively counted against the purchase price. If the family decides to move on and not take up the right to buy the house at market rates, the government will sell the property at market rates. It will then write off any “book losses” that might have occurred in the meantime.

Some keyboard operator will do the calculations and click some keys to accomplish the required transactions.

Questions:

- Does anyone lose their house as a consequence of being unemployed? Answer: no.

- Are the houses still there and well maintained? Answer: yes.

- Are the normal private contractual arrangements interfered with? Answer: yes, the bank still forecloses when the default occurs.

- Will this provoke a broadening private debt crisis? Answer: no.

- Will current or future generations have to pick up the tab because the government nationalised the mortgage defaults? Which tab exactly has to be picked up if there is one to pick up? Answer: no there is no tab.

- Have any real resources been scrapped or wasted? Answer: no

The point is that there is no “real cost” to the government at all in doing this. They could even just scrap the assets on their books and send the titles to the occupants and say congratulations. I do not recommend this strategy but it wouldn’t add any real costs to the economy at all – now or into the future.

Einhorn then claims that:

A good percentage of the structural increase in the deficit is because last year’s “stimulus” was not stimulus in the traditional sense. Rather than a one-time injection of spending to replace a cyclical reduction in private demand, the vast majority of the stimulus has been a permanent increase in the base level of government spending – including spending on federal jobs. How different is the government today from what General Motors was a decade ago? Government employees are expensive and difficult to fire.

I was interested in this claim. On first blush if it was true then it would be a wonderful result. Workers moving into the public sector do provide public services. Secure, well-paid jobs. What is he complaining about? Most of the manufacturing jobs up in Detroit etc won’t come back anyway and so those skilled jobs will be replaced by burger-flipping service jobs.

But on second blush, if you put together the other evidence that is available, his proposition cannot be true. The CBO is very close to the fiscal parameters in the US – much closer than Einhorn. If you consider the last graph it would be difficult to get the budget deficit ratio back down to below 2 per cent from its current level if a large chunk of the stimulus was going to be tied up in permanent outlays.

This is not a credible claim – if only it was true.

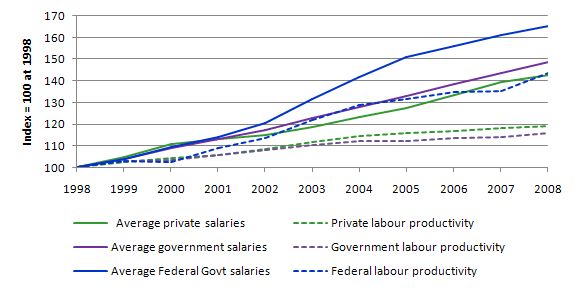

Einhorn continues to misrepresent. He quotes some very dubious Cato Institute of sectoral wage trends. You can examine their analysis yourselves. They basically show that in public earnings have risen much faster than private salaries since 2000. I had a look at the same data and come up with quite different results. They do not compare like with like.

Moreover they leave out the other side of the story – productivity movements. Consider the following graph that shows the movement in Wage and Salary Accruals Per Full-Time Equivalent Employee for the overall private; government and federal government sectors between 1998 and 2008. The graph also shows labour productivity movements by the same sectors over the same period.

All the data is available from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. I specifically used Table 1.5.6 (real GDP); Table 6.5D. Full-Time Equivalent Employees by Industry; and Table 6.6D. Wage and Salary Accruals Per Full-Time Equivalent Employee by Industry. The productivity measure is real GDP per full-time equivalent worker to reduce the bias between sectors (private sector more casualised).

The results speak for themselves. There is not the blowout in unit labour costs in the public sector as would appear to be the case if you ignored productivity. It is true that the federal government workers have enjoyed better wage gains over this period than their private counterparts. But if the BEA data is correct they have also increased their productivity per full-time equivalent worker. Further, why is the low-paid private labour market the benchmark for assessing progress?

So the first part of this critique has demonstrated that his depiction of the US economy at present is far from accurate and seems designed to inflame judgement and reinforce the view that a catastrophe is looming.

And it is to that theme that he then turns:

The question we need to ask is this: If we don’t change direction, how long can we travel down this path without having a crisis? The answer lies in two critical issues. First, how long will the capital markets continue to finance government borrowings that may be refinanced but never repaid on reasonable terms? And second, to what extent can obligations that are not financed through traditional fiscal means be satisfied through central bank monetization of debts – that is, by the printing of money?

First, you are having a crisis in the US. Here is the US Bureau of Labor Statistics link to it – 17.1 per cent. And if you don’t do something about it the situation will fester into higher crime rates; higher rates of family breakdown; higher suicide rates; etc

Second, when have the capital markets ever failed to “finance … (US) … government borrowings”

Third, it would be preferable for the US government to stop worrying about questions relating to the first issue (capital markets) and change their rules and regulations to insist that the central bank credits bank accounts on behalf of the US treasury in fulfillment of its socio-economic program.

Einhorn then talks about the origins of the recent US credit crisis – the problem of realising that companies had excessive risk:

It was once unthinkable that “risk-free” institutions could fail – so unthinkable that the chief executives of the companies that recently did fail probably didn’t realize when they crossed the line from highly creditworthy to eventually insolvent. Surely, had they seen the line, they would, to a man, have stopped on the solvent side.

Apart from taking exception to his gender-bias, the fact is that all private sector institutions carry some risk as do state and local governments in a federal system. But his overall aim is to then argue that the excessive risk has transferred to the public sector (federal level):

Our government leaders are faced with the same risk today. At what level of government debt and future commitments does government default go from being unthinkable to inevitable, and how does our government think about that risk?

Answer: no level! The US government will never default on its public debt commitments on “capacity to pay” grounds. A sovereign government can always service and retire its outstanding debt. It might default (although highly unlikely) if it believes there are political reasons for doing so. It never has and it never will is my assessment.

Einhorn admits to pestering government officials with this banality – “I recently posed this question to one of the president’s senior economic advisers”. Answer: “the government can print money, and statistically the United States is not as bad off as some other countries”.

So if this truly represents the views of the senior economic adviser in the US I feel sorry for that nation’s citizens. First, the “printing money” representation is highly misleading and unhelpful. Governments spend in the same way whether they raise taxes; issue bonds or do neither. In every case they are making credit entries into the banking system (or issuing cheques).

Mainstream economists like to tell students that governments have three choices when they spend. First, they can raise taxes – store it in a box and then dole out the contents as spending. Second, they can issue debt – store the funds in a box and then dole out the contents as spending. Third, they can just run a note printing press and spend that way.

Even as an educational heuristic the construction is unhelpful. Governments impose taxes to drain demand. They issue bonds to defend short-term interest rates. And they always spend by crediting bank accounts.

But further, the statement that “statistically the United States is not as bad off as some other countries” has no meaningful content. This is just ratio fever – whether the deficit and debt ratios are higher or lower is largely irrelevant (that will probably just signal the relative depth of the private sector spending collapse).

More importantly, a sovereign government can always spend what it wants. The Japanese government, with the highest debt ratio by far (190 per cent or so) has exactly the same capacity to spend as the Australian government which has a public debt ratio around 18 per cent (last time I looked). Both have an unlimited financial capacity to spend.

That is not the same thing as saying they should spend in an unlimited fashion. Clearly they should run deficits sufficient to close the non-government spending gap. That should be the only fiscal rule they obey.

Einhorn goes on to discuss why the US is likely to go the path of Greece with bond markets revolting against further funding requests from the US government. Just the style he uses is misleading:

I don’t believe a United States debt default is inevitable. On the other hand, I don’t see the political will to steer the country away from crisis. If we wait until the markets force action, as they have in Greece, we might find ourselves negotiating austerity programs with foreign creditors.

Why not say that historically the United States has never defaulted end of story. Why not explain how the funds that the bond markets provide to the US government under the unnecessary obsession the latter has in matching every $ of net spending with a $ of private debt – that the funds came from the government in the first place. The government just borrows its own spending back.

Why not actually educate people about how the US dollars that China holds never leave the country and come only from the US government not the Chinese government? Why not explain how the monetary system that Greece is constrained by is very different to that which the US government runs as a monopoly issuer of the currency?

That would require too much thinking and wreck his argument.

He then starts on the “Federal Reserve will start printing money and inflation is inevitable” argument:

Despite the promises by the Federal Reserve chairman, Ben Bernanke, not to print money or “monetize” the debt, when push comes to shove, there is a good chance the Fed will do so, at least to the point where significant inflation shows up even in government statistics.

That the recent round of money printing has not led to headline inflation may give central bankers the confidence that they can pursue this course without inflationary consequences. However, printing money can go only so far without creating inflation.

Remember my earlier comments on “printing money”. But, he reveals a fundamental lack of understanding of what the federal reserve has been doing in recent years expanding its balance sheet. Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Expanding the money base by net spending impacts on demand for real goods and services which carries an inflation risk under certain circumstances. Those circumstances are not even remotely in place at present to present any risk at all. Expanding bank reserves by central bank purchases of say, long-term financial assets, adds nothing to aggregate demand.

The only way this might have added to demand would be via the interest rate channel such that the purchases of the long-term assets would drive the yields down and perhaps stimulate private investment. It is a very inefficient way to stimulate demand and has had no discernable effect.

Meanwhile house prices are still falling in the US and the IMF is predicting major further downward price adjustments.

The rest of his Op-Ed is an attack on “easy money” (that is, low interest rates). As regular readers know, I would keep the rates where they are allow all other risk-weighted asset yields to consolidate at this new “lower” return structure, and shut down a signficant portion of the central banking system!

Apparently, Einhorn has sympathetic minds in the top echelons of the the US government. Wannabee President Hillary Clinton gave a National Security speech in Washington D.C. on May 27, 2010. In question time, the moderator said that “even in the last week where senior military figures have said that the deficit is at least potentially if not actually the single biggest threat to the national security of the United States”. To which Clinton replied:

And I think the concerns that you and others are hearing from our military leaders are certainly matched by our civilian leaders. I think the President is very well aware of the long-term threat that our deficit and debt situation pose to our strength at home and abroad. And other nations, certainly during the last year, put that concern on a back burner while everybody tried to stimulate themselves out of the deep recession that we were facing. But now the conversation has returned to talking about long-term, sustainable growth. And sustainable is not just about the environment; it is about our fiscal standing.

This is a very personally painful issue for me because it won’t surprise any of you to hear that I was very proud of the fact that when my husband ended his eight years, we had a balanced budget and a surplus. And that was not just an exercise in budgeteering; it was linked to a very clear understanding of what the United States needed to do to get positioned to lead for the foreseeable future, far into the 21st century.

Goodbye America! Fancy being proud of running surpluses which were part of a dynamic that allowed financial engineering to emerge and force massive volumes of credit onto the private sector with the resulting build-up in debt. This was also the period when government policy was relaxed to allow financial markets to cook up their poisonous concoction that has now exploded.

If I was Clinton I would be recruiting educationalists from Texas to see if they might rewrite history a bit to blur the Clinton (husband) era altogether.

There is absolutely no threat to US national security from any size of deficit. There is no connection. They are trying to argue that the government might have to compromise its military and invasion program because of austerity demands.

First, the austerity demands should not be made.

Second, cutting US military spending and agression would probably increase US national security. The US government might usefull offer funds to implement full employment programs in countries they are current invading. It would be much cheaper anyway than to bomb them day-in-day-out with very little effect anyway. And, maybe, more people will start having a higher regard for the US and be less likely to want to bomb the hell out of the place.

Clinton went on:

We cannot sustain this level of deficit financing and debt without losing our influence, without being constrained in the tough decisions we have to make … make the national security case about reducing the deficit and getting the debt under control.

The only thing I can say in response to this is what purpose does the Peter G. Peterson Foundation now serve. The Government has now taken over their job. Pete should just close shop and have fun.

Conclusion

I hope my attempts at fiction will be better than the writing I have been discussing today.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow with answers and discussion on Sunday.

That is enough for today!

“Why not explain how the funds that the bond markets provide to the US government under the unnecessary obsession the latter has in matching every $ of net spending with a $ of private debt – that the funds came from the government in the first place. The government just borrows its own spending back.

Why not actually educate people about how the US dollars that China holds never leave the country and come only from the US government not the Chinese government? Why not explain how the monetary system that Greece is constrained by is very different to that which the US government runs as a monopoly issuer of the currency?”

The government borrows in the debt markets before it spends – because it does not borrow by way of credit or overdraft from the central bank.

The US dollars that China holds come predominantly from the US commercial banking system.

And they come for the most part either from deposit accounts or new bank lending.

Government spending comes only from its deposit account with the Fed.

Many institutions issue US dollar money liabilities – the Federal Reserve, US domestic banks, and foreign banks issuing US dollar credit. The focus on “monopoly issuer of currency” obscures the breadth of these sources.

In fact, the government is the only relevant institution here that doesn’t issue currency – because it has no line of credit or overdraft privilege with the central bank – at least not until Congress grants it.

In the latter sense, the central bank is the lender of last resort for the government, although MMT describes it as if it were the lender of first resort – which more accurately is the operational objective of the MMT “no bonds” proposal.

The government spends what it borrows through debt. MMT would like the government to spend from central bank credit (effectively), without issuing bonds. In neither case does it borrow back what it spends.

Fact or fiction?

Anon,

My observation with what you are poking at here is that you may miss the fact (or do not apply correct context of) that the Fed is the Fiscal Agent of the Treasury by choice of the Treasury. The Fed works for the Treasury as the Govt ‘Agent’, not the other way around. You seem to imply that the Treasury is somehow beholden to the Fed generally. Resp,

This is off topic, but there is an economics conference in Greece 26-29th July (come and join the riots). I intend submitting a MMTish paper based on this: http://govtdebt.blogspot.com/ and will do a presentation if asked to.

300 word abstracts need to be in by 31st May. Site: http://www.atiner.gr/docs/Economics.htm

Abstracts to: atiner@atiner.gr

How about this ?

“Backed by the powers written in section (k) of Title 31 – Money And Finance § 5112 Denominations, specifications, and design of coins of the United States code that The Secretary may mint and issue platinum bullion coins and proof platinum coins in accordance with such specifications, designs, varieties, quantities, denominations, and inscriptions as the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, may prescribe from time to time., the US government makes various promises to its citizens. Because the government spending increases the banks’ settlement balances and that it is considered to be inflationary by mainstream economists, the government is required to finance its spending through the issuance of government debt. To make sure that this condition is followed strictly, the Treasury is required to not go overdraft on its account at the Federal Reserve. It is thought that since the money supply is fixed by the Federal Reserve, the markets will automatically constrain government spending.”

So even in the present system in the United States, the government can issue currency. The Federal Reserve will credit the Treasury General Account and government cheques can only bounce if they don’t know the laws well. There is a lender of the last resort to the government – itself. The constraint implied by the neoclassical analysis doesn’t apply since the money supply is not fixed.

In the present system they may act as if they are constrained – which is the case, but they are not actually constrained. The simplest way to prevent an overdraft without breaking any law or constitution is for the Treasury to hand a coin of high denomination to the Fed. As Beowulf says, Tim Geithner can hand-deliver this coin.

You say, “Clearly they should run deficits sufficient to close the non-government spending gap.”

Really? That is what they are supposed to do?

When you start with that as a core assumption everything else is just mud. Sorry.

bk

Anon,

Further to my earlier comment, I will try to discuss what a constraint really means. The government budget constraint is

G – T = ΔB.

where ΔB is the proceeds from bond issuance. A neoclassical will interpret this as saying that G is the residual. However MMTers will say ΔB is the residual. The no overdraft condition actually seems to give an indication that ΔB is the residual. However, because of the “platinum coin of any denomination” issuing power of the Treasury secretary in the US, the no overdraft condition is not that meaningful.

Also, you said that “The government spends what it borrows through debt.” However that is not the case even now. That is the case for a private firm but not the government. G determines what ΔB is – as the MMTers argue – instead of ΔB determining G. How governments behave when debt/gdp ratios rise or deficit/gdp rise is a different question. That is a question about their behaviour, not an inherent constraint.

Anon,

I’ve seen your questions before and I’m hoping one of the MMT bloggers will care, one day, to dedicate entire post to address them. You would think that loyal readers of this and related blogs deserve it. Those who have no clue what is being spoken of here, can refer to the post Marshall’s latest at WM, renamed Marshall’s longest due to the endless number of comments.

Even with government bonds/borrowing, one still has to explain how the government injects spending into the economy. Either you take the view that the government only borrows private bank-created money (which would certainly have interesting effects), or that the government spends prior to borrowing.

Government borrowing is a combination of two activities: 1) private entities/foreign countries with excess dollars wishing a low risk asset, 2) accounting treatment of government spending. These two functions are combined into a single debt sales process; it can confuse onlookers by appearing as if the government is borrowing only from the private sector.

Besides the ideological confusion, the only real problem I see with government borrowing/debt sale is the transfer payment to the primary dealers for their fine service; otherwise I happen to like accounting.

I’m interested in the mechanics by which the government and primary dealers handle a bond offering with regard to the government spend/recapture via debt. Obviously, private demand for government debt (safe assets) determines interest rate, which is targeted by the CB. But private demand volume may only cover a fraction of total debt issuance. Given a liquidity crunch, one might expect that massive government debt issuance would be met with an auction failure and/or tremendously high interest rates to attract scarce cash, but we find the opposite – all debt issuance met at low interest rates – with the excuse given as a “flight to safety”. It seems clear that the actual private demand for debt offerings sometimes only partially meets issuance requirements. So, how is that debt funded?

When bank accounts are credited prior to debt, I imagine this means accounts resident at the primary dealers, who turn around and now have funds to “purchase” the balance of the debt issuance. It should then be clear that this is simply an accounting transaction to “authorize” the additional spending. However this is coordinated between the primary dealers and Fed, whether this happens simultaneously or one just before the other is academic. I might have this completely wrong – the mechanics may go through an altogether different path – but just curious if anyone has any insights.

Another food for thought regarding heterogeneity another source of imperfection (in a pervious comment I dealt with asymmetry) and two more sources to come in other comments. I write these comments here because 1)Bill is a generous host and b) this a blog encourages alternative ways of thinking and maybe we can all sharpen our understanding with some debate of alternative ideas.

Heterogeneity, when present, has implications for unit formation and behavior. The drive for unit completion (an operational process) of parts implies a rise in the property of divisibility and an opposite drop of diversity (Iam summarizing here, there is alot of math behind this). We can assure the stability condition for this source of imperfection if we close the “square” of nonlinear dialectics of interdependent properties of parts. This requires that a rise in divisiblity reduces diversity and a drop in diversity increases divisibility. Notice that what stops the drive of completion is complexity by imposing an entropy upon the process (Not discussed here because it adds another level of sophistication). Notice that divisibility is a vertical property of the generation process and diversity is a horizontal property of the allocation process of completion. Given the level of completion of the assembly of parts, the mix of diversity and indivisibility identifies a degree of heterogeneity.

As an example, heterogeneity requires non-continuous units seperated by a “punctuated” equilibrium. For a seller/issuer it implies product differentiation and for a buyer/investor it implies differentiated preferences and the elasticities for both are limited. The presence of indivisibility and diversity means the presence of persistent differentials among seperated markets(segmentation) and price signals become partially ineffective. Allocation becomes lateral with gaps and overlaps and generation becomes constrained by leakages of indivisibility. To put it differently the Euler equation does not apply as products are not “exhausted” by factors and utilities and the Taylor completion series has a polynomial specification with a remainder term and not an arbitrary function ivariant to specification. Notice that units can not be aggregated and compared subject to a representative unit. Furthermore, arbitrage and intermediation are neccessary but not sufficient conditions to eliminate differences. In summary, heterogeneity is another source of the Keynesian equilibrium stasis.

Anon/BX12

Fact or fiction?

In order to settle tax liabilities or purchase a Treasury, the payor (if it is itself a bank) or the payor’s bank must have or otherwise obtain reserve balances in order to complete the transaction. While numerous private financial institutions can and do create dollar denominated liabilities, none of these institutions in fact create reserve balances on their own (that is, in the absence of interactions with the Fed or the Treasury) as a result of their spending, lending, or credit creation activities. As such, it is only as a consequence of reserve balances created via previous spending by the Treasury, a loan/overdraft from the Fed, or other technical changes to the Fed’s balance sheet, that tax liabilities or Treasury security purchases are ultimately settled with the Treasury.

I went to college, I studied economics. I manage part of a Sovereign Wealth Fund, and I have no clue what your saying. What I do know is I bought gold at $400 several years ago and it’s $1200 today. I also know I bought candy bars for a nickel as a kid, and the same size bar cost $1 now. In my book thats currency debasement. Said differently, We’re getting Fcuked!

You can spew that The deficit doesn’t matter, the Fed printing money doesn’t matter, etc, etc. all I know is the government either through taxation or inflation is stealing from me. If that isn’t a call to arms, what is?

Scott,

Dunno, but I was thinking this : what if the state of say Oklahoma teamed up with a major bank, or even better, set up its own banking arm, while still operating in the US currency system? How far would the analogy take us towards understanding the difference/commonality with how the US gov operates, you think?

Ahhh … Finally. An FX Trader/Hedge Fund guy plus a Sovereign Wealth Fund Manager weigh in and share their wisdom with the uninitiated proletariat. It’s amusing to read complaints of some Sovereign Wealth Fund Manager for being constantly screwed by the Sovereign. Must be a really hard time to accept big monthly checks in some debased Sovereign Currency? My condolences!

BX12 . . . what’s your point? Sorry, not seeing it.

Sherman McCoy,

Most of the Sovereign Wealth Funds have not had particularly sterling investment records. A good number of them were buying Citi and Merrill well above current prices. It’s very clever that you bought gold at $400. Good for you. So what? I bought zero coupon bonds in 1984 when they were yielding 14.75% and all of the “economic experts” told me that I was buying “certificates of confiscation”. Are you trying to suggest that you’ve never made a bad trade in your life? Or is the gold purchase a demonstration of your supposed expertise in economics? Perhaps if you studied accounting 101, you might have a better idea what Scott and Bill are saying. Despite being involved in finance, there is nothing in your comments which actually demonstrates an understanding of monetary operations or basic accounting identities.

Probably not your fault insofar as actual monetary operations are seldom taught in the economics departments of many schools.

But, as a pure factual matter, the annual govt deficit equals, to the penny, the change in the total of Tsy secs (time deposits in Fed accounts), reserves (clearing balances at the fed), and cash in circulation.

And the cumulative govt deficit- the total debt- is equal to tsy secs, reserves, and cash in circulation. to the penny.

And, also as a point of fact, the total debt is equal to the total net savings of dollar denominated financial assets of the non govt sectors, to the penny.

In other words, as my friend Warren Mosler says, you could change the name on the national debt clock in NYC to the world net dollar savings clock and leave the numbers alone.

Additional, again, a basic operational matter, not theory the government on a consolidated basis does spend simply by changing numbers up on its own computer and taxes by changing numbers down on its own computer. It doesn’t store anything or have a “lock box” which it can unlock and deploy for future generations.

The govt never has nor doesn’t have dollars, any more than a football scoreboard doesn’t have the points they post a team’s score.

Yes, there are clearly political debates to be had about about how much a govt should spend or tax.

But if you don’t at least start with the operational realities you’re just spewing empty rhetoric, regardless of how successful a gold trader you might be.

@Marshall Auerback: so even on this site should one criticize the dominant theme – as Sherman McCoy did – ad hominem attacks follow? I for one did study accounting in college, don’t manage anyone’s money but my own and I fully concur with Sherman’s point. The government is quietly stealing the value of my dollars via inflation.

You repeatedly state that government deficit or accumulated deficit whichever, is equal, “… to the penny” to treasury securities held at the federal reserve (or the change therein) + bank reserves at the fed + currency in circulation. Further, the total government debt is, “… to the penny” equal to the net dollar savings. Well, exactly and duh! When the government creates money (prints dollar bills, wacks a keyboard, whatever) the money goes somewhere. So I believe you’ve stated exactly nothing.

Sherman’s point, and mine, is that accepting the governments ability to print money at will is nothing less than permitting the government to confiscate private property by debasing the currency. And, yeah, that means those of us in the private sector are screwed.

George and Red,

Yes, there’s so much inflation right now, I can hardly believe it! And Japan, too, particularly with 3x the national debt as the US . . hyperinflation there. I see what you both mean. Call to arms, indeed!

Anon,

I really fail to understand the point you are making. You seem to have difficulty distinguishing between horizontal and vertical money creation (only via the latter can one create new net financial assets), and distinguishing between various kinds of monetary systems, notably that of the US, Japan, Australia, Canada, etc., on the one hand and the euro zone on the other. In regard to the first point, clearly the fact the the euro zone does not have a supranational fiscal authority does mean that the ECB will not operate precisely like the Fed (even though the ECB always likes to use the Fed as the direct comparison, suggesting that the national central banks are akin to the regional district banks at the Fed-this is incorrect). Scott, Warren, Bill and virtually all adherents of MMT repeatedly stress the difference b/n US and the euro zone: in the former, the US Congress is both the one doing the spending and the one that tells the Fed whether or not to give it an overdraft. Not so for EMU countries, and obviously not so for American states. Likewise, the individual nations within the euro zone cannot create currency and therefore do functionally operate with an external debt constraint, as does a country with a pegged rate regime (such as Latvia or Estonia) or American state, which is a USER of the currency ISSUED by the US Treasury.

Given these fundamental points, the REAL issue for the US–regardless of self-imposed requirements not to run overdrafts (and it’s not altogether clear that the Treasury can’t run overdrafts, because they get a bit uneasy when the question has been posed)–is that it can issue its debt at roughly the Fed’s target regardless of the size of the issue. Not so for Greece, Portugal, Spain, Italy, in fact any euro zone country and that’s why all of the EMU nations are in crisis.

In terms of the operational aspects of MMT, you won’t get a better illustration on how it actually works than reading Scott Fullwiler’s excellent work on this stuff. But the theory is important. The real point of having a theory of how all this works is to be able to understand the options available to policy makers. Hence the need for a general model.

Having read your comments, I fail to see how starting from your understanding helps. In fact, I’m having a hard time understanding your actual point. What would you have policy makers do? Perhaps, if you focused on the latter question, we could understand the basis of your disagreement better.

Redstar,

I criticised Sherman McCoy, because frankly, I don’t think arrogance is a particularly attractive quality. Telling everybody what a great fund manager you might be does not constitute an argument. You’ll note, by contrast, that I didn’t engage in an ad hominem attack on Anon because he stuck to the issues (not very clearly in my view, but I’m trying to get a sense of what his real objections are to the theory).

As far as creating inflation or debasing the currency, yes, the government does have that ability and we always make it a point to indicate that the inflationary/real resource constraint is an important one. That always seems to be ignored with amazing regularity by our critics. If you want to engage in a proper debate, important to get your facts correct, rather than simply spew out tired slogans which are not reflected in our writings. We are trying to do serious analysis, Not resort to caricature. Sherman says, “candy bars were 5 cents now they’re $1”. So what? Is he, or are you, trying to suggest that he buy less candy bars today? The reality is that he can probably buy a lot more candy bars now, so what’s the problem? This whole “currency debasement” argument is a huge red herring.

Dear Sherman McCoy at 4.02 (and RedStar)

And what is the average nominal wage level now compared to when you were a child.?

Currency debasement can only be a real concept. Comparing to nominal price levels at two points in time of one good or service tells us nothing at all about the movements in the real purchasing power of a unit of account.

And as a marketing tip: In Australia, we ban arms sales (other than for sport and then only under very controlled circumstances). To get the gold bugs going here you will need a more inclusive slogan.

best wishes

bill

Marshall and Scott,

Sometime ago I developed a simple reduced form equation which I also presented in a comment in this blog.

ΔΜ= ( V/k(1+i)^2 +1) ΔΝFA

V is the velocity of NFA change across financial assets or an index of the “pecking order” horizontal allocation of financial assets.

k is the income multiplier or an index of the vertical generation of income from the change of spending sources.

i is the short term interest rate in the control of the CB, that(1+i) squared adjusts (V/k) with a curcature and shows the negative effect of short rates.

Notice that there is no money multiplier here and changes in the money supply is subject to behavioral parameters of spending and risk taking preference or technical change in financial accounts. A higher velocity parameter from risk taking preference or technological change in the financial sector and a lower income multiplier (higher MPS) requires a higher change in the money supply. An absolute risk taking avoidance or V=0, implies that ΔΜ=ΔNFA.

“Why not say that historically the United States has never defaulted end of story.”

Because that statement would not be true.

See:

http://www.aei.org/docLib/Deficit%20Endgame.pdf

“In other cases, such as the United States during the Great Depression, default (by abrogation of the gold clause in 1933) was a precondition for reinflating the economy through expansionary fiscal and monetary policy.”

Many of your other errors are just flaws in logic, instead of somewhat harmless misstatement of facts like the example above. Just because something has never happened, doesn”t mean it can”t happen. Read the Black Swan sometime or John Hussman.

The interesting thing about this article for me (as an investor) is that now I understand what the thinking is of people who are buying TIPS at sub 1% real yields and 30 year Treasuries at sub 4% yields.

Sherman McCoy, the price of gold increased even in Japanese yen and they had deflation for 20 years. So what exactly is your point?

On the other hand several years I had one heavy laptop and felt proud. Today I have 3 working laptops and one for back-up. Several years ago I was using dial-up and was waiting for pages to load while counting my traffic. Today when any pages takes more than a second to load I get annoyed. Several years ago I used to pay lots of money to make international calls. Today in many cases one can call for absolutely free. And one can go on and on.

This government money printing stuff is really great!

And btw I am also a portfolio manager now. And studied physics at the university which is how I missed this mainstream Econ 101 nonsense.

Dear Maverick

That is not a default under a fiat currency system. Sorry. That is what is being discussed at present.

best wishes

bill

Scott, Anon, Marshall

Marshall Auerback says:

Saturday, May 29, 2010 at 6:44

I hope Marshall noticed the over 500 comments that your blog post has motivated at WM.

EUROZONE:

I’m glad he is answering like this :

“You seem to have difficulty distinguishing between horizontal and vertical money creation (only via the latter can one create new net financial assets), and distinguishing between various kinds of monetary systems, notably that of the US, Japan, Australia, Canada, etc., on the one hand and the euro zone on the other. ”

as I have implored that someone take a stance on whether gov spending of EZ members is horizontal or vertical. I’ll count your his as in favor of horizontal for the EZ. For now, I think it’s counter productive to even considering the EZ before clarifying first principles.

NET FINANCIAL ASSETS : ACCOUNTING

A transaction (money creation) is deemed horizontal if one party’s liability is considered another’s asset, and conversely, as happens between private entities. The bank’s loan recipient has a deposit as his asset and the loan as a liability, and conversely for the bank.

If the Fed credits a private account it appears in the client’s bank account as a deposit (Liability) and reserves at the Fed (Asset). Conversely, the Fed has increased reserves on the Liability side, and the private bank’s IOU in its Assets.

To say that a net financial asset was created for the non-gov sector is to postulate that the bank’s IOU towards the Fed is void. The expression “net assets” does not exist other than in MMT.

NET FINANCIAL ASSETS : ECONOMICS?

A private bank can create money for as long as its capital > 0, or else bankruptcy, by law, kicks in mechanically. In fact, it can continue to do so as long as it accounting capital, not economic (marked to market), is positive, as we’ve learned from the subprime crisis.

The only difference I see with the Fed, is that it has the privilege to continue creating money even if capital < 0. I see the privilege, but I don't see the economic meaning of financial assets.

SPENDING BEFORE TAXING

Banks, in the simple minds of standard economists, offer loans to allow their customer to spend (consumption/investment) before they collect anticipated receipts (salary/return from investment). They include the government as a not so special case by treating Tax as simply the fee paid for the services of the state, or a donation in the case of fiscal transfers.

This has, at least, the appeal of simplicity, which MMT agrees with, but only for the private sector. For government, it claims that spending comes before taxing. But spending is crediting bank accounts, where's the difference with the private sector?

Please feel free to interject with TRUE/FALSE or more.

Thanks.

Sherman said:

So, are you planning on keeping your gold or selling it for a currency? If you never sell it you haven’t “made” a penny. Good luck trying to use the gold to actually buy something.

You’ve been fcuked alright, by your Austrian economics upbringing. Money is NOT a commodity. It is that which all commodities are priced in. You act like you want gold but you want currency. You wouldn’t be bragging about how many more dollars it was worth if you didn’t want dollars.

Try telling me how valuable gold is without using a currency in your answer? ……………………………..I’m waiting!!

Bruce Krasting, it seems you apparently skipped the Saturday Quiz of 5.22.10. See the answer to Question 4 here for clarification of what you call a core assumption. It is not an assumption, but an implication of an accounting identity.

Interesting the amount of new traffic here lately. I think the word is getting out and that is a good thing. The Krastings and other commentators like Sherman Mccoy are getting nervous. People might start to wake up to the reality of what currency is.

Bruce K. raises an important point.

Households and businesses are able to grant themselves an unlimited amount of income by borrowing, at least over the short to medium turn. Once they do so, the economy becomes accustomed to this level of extra-median wage income — prices rise and median wage shares stagnate, as businesses are able to sell goods to those who borrow to pay them rather than to those who can afford to buy them.

I see no reason why, when the borrowing bubble pops, the government should step in and guarantee the same income level. That is not a society that I want to live in.

What is needed is a definition of the amount of additional income the government should supply based on sustainable patterns of wages and investment, not based on the insane “desires” of a few households to pile up more and more wealth.

RSJ’s comment (3rd para) is what I have tried to get an answer for when questioning MMT bloggers on Debt Deflation and Naked Capitalism, on at least four occasions, without luck!

Deficit spending now will only sustain the highly distorted status quo which is drastically skewed towards the wealthy in the western world.

What happens, in extremis, if every country in the world wants to run large deficits? who funds those?

As I’ve said before, I do get your accounting approach, but where are the controls? Who determines what is an acceptable deficit for the US? Can South Africa just run up the same deficit, or Nigeria, or Somalia, or must they just accept the scraps from the table?

Who determines what the optimal employment rate is for a country or the world at large?

The way I see this is that the top accounting entry is credit “the world” resources, debit “mankind”, and all this theory aims to do is perpetuate or accelerate the momentum of a very, very distorted world.

In isolated cases it must work for sure, but not on the global basis and certainly not under current circumstances.

Fortunately as Hugh Hendry reiterated when slapping down Jeffery Sachs on BBC TV, the markets run the world, not academics.

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/hugh-hendry-i-would-recommend-you-panic

And yes, I know for now they are run by fraudsters in the very countries I oppose supporting, but that too will slowly!

Personally I thought Shermans and RedSt8r comments yesterday refreshing. Any intellectual challenge is always welcome. Thus I woke up this morning with inflation worries on my mind. And like any old-fashioned hardcore Bundesbank banker I felt the immediate urge to check M3. Luckily the people at shadowstats.com continue the M3 time series for the US. And indeed the picture is grim. Late 2009 M3 started to shrink? Over the first quarter 2010 M3 contracted by a whooping 10%. (Caveat: my envelop calc over coffee.)

Hmmm … I changed my goggles to some sexy Friedmanite ones and I immediately understand the candy bar concerns of Sherman. Although I wouldn’t worry so much about candy bar prices going up to US$ 1,50 next year there’s certainly a danger that Shermans favorite candy bar isn’t around at all next year. To my knowledge such a contraction of the broad money supply happened last time in the late 20s and early 30s? (Please correct me on this if I’m wrong.) Now a shrinking M3 is certainly not a recipe to kick-start growth. It’s more of an invitation for future economic disasters.

So yes Sherman and RedSt8r are correct with their general assessment: They are screwed by their government. The US government with assistance from the FED seems intend not only to confiscate private sector property but to destroy it. How evil is that?

Stephan,

The Fed has stopped publishing M3 and as you said published by other people. I am not sure how accurate that data is going to be. M3 also included repurchase agreements (that too only using primary dealers’) data. The fall in M3 is mainly due to the fall in repos, I would imagine.

Gareth, the fact that current budget deficits go to profits of big banks/companies in every single developed country only shows the failure of democratic process there. And it fails because people do not understand how the power of money can be leveraged in their own favour. Instead they “buy” austerity measures targets at salary cuts. And then you get rich and big companies being worried about their wealth and demanding even more austerity measures.

Optimal rate of employment is a very easy question. It is the one when everybody who wants to work works.

If markets run this world then there are plenty of examples where markets did not run anything but human civilization made huge progress: the whole history of humankind until approximately 1970s

Sergei, I would say that is still a most imprecise measure for employment and leaves plenty of scope for abuse to favour the wealthy classes, which goes back to my point of where are the controls?

Secondly, I would argue it was up until the 1970’s that the market worked most efficiently with limited economic theory distorting the natural re-balancing that happened more regularly.

My point about the market ruling is that for the last 20 years intervention of one kind or another has postponed the natural corrections, and advocating deep deficits now is just another postponement to favour “unnatural”, above trend excesses.

Gareth, this is the only possible measure of employment which will produce a situation where involuntary unemployment is ZERO. You do not need to control it, you need to give every willing person a job. This will by definition level the differences between wealthy and poor and can be a single most powerful and easy step to do it.

I have very little belief in self-correcting nature of markets and their sacred efficiency and value. There are plenty of examples from history of this civilisation which clearly show that any need for so called markets is hugely exaggerated. Take China: do they respect free markets? Yet the results are clear and non-disputable. Take USSR: no markets at all, but they rebuilt the country after WWII without any external help. And so on.

In the last 20 years free markets created numericals cases of economic imbalances. That is the case because the only thing free markets are interested in is profit. Society is never interested in quarterly results yet this is what drives free markets. And when a bad quarter arrives people are sold a need to help free markets. So government intervention was required to “fix” those free market “issues” but it never fixed the root problem of it – incompatibility between goals.

Dear Bill,

Sometimes I have the strange feeling that we live in a fictional world where people don’t know basic things like left and right or up and down.

You and your MMT colleagues should be spending your time mostly on TV economics or politics shows and constantly be alarming the general public that the emperor is actually totally naked. Why haven’t I seen any of you guys on TV? What does it take to get there? We all should be more aggressive in making the noise – it’s our responsibility!

To Bill and other free-thinking Economics enthusiasts lurking here,

I am a satirist, media worker, writer, and bon vivant (not Christopher Hitchens)… I have been reading this blog for the past few months. I would like to assure the readers of this blog, that, as someone who is looking to rejoin the media industry in coming months, I personally will be doing my best to increase the knowledge of MMT amongst other media ‘professionals’; closed-minded and stupid that most of them in the mainstream seem to be however.

… My initial interest in MMT arose about two years ago when I studied Economic Anthropology. For some extra reading, I happened to come across Thomas Crump’s ‘The Anthropology of Money’. It’s a must for anyone wishing to understand the modern economics system from a phenomenological view, or from a philosophy of ‘following the object’ (in this case, currency from its creation). This is what I think Bill does well here at this blog.

For anyone’s interest, below is a very good overview of the arguments and areas of study involved in economic anthropology:

http://thememorybank.co.uk/2007/11/09/a-short-history-of-economic-anthropology/

Stay cool groovers,

Serkan Ozturk

Sydney, Australia

http://tripoutcorner.blogspot.com

Gareth

“RSJ’s comment (3rd para) is what I have tried to get an answer for when questioning MMT bloggers on Debt Deflation and Naked Capitalism, on at least four occasions, without luck! Deficit spending now will only sustain the highly distorted status quo which is drastically skewed towards the wealthy in the western world.”

Not if its targeted at those people (like a JG and payroll tax holiday) which A) need a job any job to renew participation in the economy B)will not save their additional income but will instead use it to pay off credit card debts etc. Yes this will eventually trickle up by making financial institutions healthier but the target is not banks and investment firms.

——————————————————-

“What happens, in extremis, if every country in the world wants to run large deficits? who funds those”

If the country issues its own currency, IT funds itself

——————————————————-

“Who determines what the optimal employment rate is for a country or the world at large?”

Offer a job to everyone who WANTS one. If the dont accept than they arent unemployed, they are CHOOSING not to work.

————————————————————————————-

“The way I see this is that the top accounting entry is credit “the world” resources, debit “mankind”, and all this theory aims to do is perpetuate or accelerate the momentum of a very, very distorted world”

Actually, currently the world is distorted but not in the direction Mr Mitchell advocates. A proper sized financial sector and a pool of jobs to keep everyone who wishes with some sort of employment will go along way to removing the distortions our financial sector places on the real economy.

How, suddenly in 2007/2008, could so many businesses that were producing stuff we wanted and employing people just “run out of money”? Where did it go? Did we suddenly lose the ability to push a computer keyboard key? Yes some people had more bills than they could pay but why should so many other people who werent in that situation have their jobs in jeopardy just because certain ratios or spreads were making “finance” guys uncomfortable. I see lots of distortion but not in the same place you do.

——————————————————————————

“Fortunately as Hugh Hendry reiterated when slapping down Jeffery Sachs on BBC TV, the markets run the world, not academics”

I’m not sure we should take solace in that fact. Markets work as poorly as academics at times and dont have the ability to learn

Johnny One Note Here

(a.k.a. -Central Government Planner on the MisesBlog)

Bill’s excellent point about the fiction of government deficits being so thoroughly yet ignorantly decried as cause for panic and economic reconstruction a la the IMF – whoever the hell THEY are – shows the importance of, and need for the UNLEARNING of monetary system theory via implication and innuendo(do NOT go down that road, Economists), and a transition toward the study of the national economy on the basis of monetary sovereignty and just what a money system actually is and how it works.

My own idea for providing the proper forum for that ‘unlearning and re-education” process is on something called youTubes.

The Fiscal Sustainability Teach-In videos could be a good starting point for that venue.

Most writings on this page are a mere few minutes in the stating and the reading when completed.

I jst think that we will make more progress in educating people with the medium that is being used by those half my age and younger.

Like a BillyVlog.

So finally, while Bill has alluded to it here again, the issue of who FUNDS the government deficits is the main boogeyman of the average reader on whether deficits Do matter or DO NOT matter – a tenet of the MMT.

There is no reason for anyone to fund government deficits when those deficits are necessary to ensure the soundness and stability of a properly functioning economy, and whether done through a platinum coin so delivered to the Fed, or through the assertion and implementation of monetary sovereignty is optional, given the necessary reforms.

What is significant is that we the people own and have the power to control every aspect of the nation’s money system and it is obvious that the private machinations of money creation now threaten our rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Take it back.

The Money System Common.

Bx12 says:

Saturday, May 29, 2010 at 12:05

“If the Fed credits a private account it appears in the client’s bank account as a deposit (Liability) and reserves at the Fed (Asset). Conversely, the Fed has increased reserves on the Liability side, and the private bank’s IOU in its Assets.”

Let me clarify that I’m looking at the case where the gov, say, wants to encourage investment, say and hands outs money to a contractor that I call Client. I’m treating the Tsy as embedded in the Fed. Let me now correct the statement above which, as it is, is sloppy:

Bank

———————

Assets : Reserves

Liability : Deposit

Client

———————-

Assets : Deposit

Liability : Net Worth

Should the Client get his money though the regular channel:

Bank

———————

Assets : Client IOU

Liability : Deposit

Client

———————-

Assets : Deposit

Liability : Bank loan

Recap :

From the Client’s standpoint if he gets money from the Fed, it counts as Net Worth i.e. he can keep it, whereas if he gets it through the regular channel, he has to repay it eventually. That’s why in the former, we talk about net financial assets being created. That’s a postulate, not an explanation. I maintain the rest of my previous post and its questions.

Bx12,

The two situations you are comparing are comparing are different. In the first case, its a sale of finished product and in the second case its financing investment. These two are different. However, you are going in the right direction about thinking about how an economy works.

Ramanan,

As I understand it, bank loans are meant to provide a bridge between expenses and receipts, whether it be consumption/investment and salary/return on investment. In the case of the private bank loan, it has to be repaid, or else the bank runs out of business. Not in the case of the Fed, which gives rise to the label “net financial asset”. Again, a postulate, not an explanation, in my eyes.

A carpenter can go directly to the wood merchant, rather than the bank, and hand him an IOU in exchange for wood. The value of the IOU stems from the anticipation that the carpenter’s work will pay off sufficiently that he can repay it. In turn, the wood supplier can trade the carpenter’s IOU for goods, for his own consumption etc.

Let’s say that the carpenter let’s the wood rot in his backyard, due to laziness or lack of demand. He will not get paid (receive an IOU from a client), so the value of his IOU becomes zero. The wood merchant will have to take a loss, perhaps run out of business.

The bank only serves to guarantee the trust of the system (they will, in this case, assess the carpenter’s ability and the demand he is likely to face) and facilitate settlement between parties.

The government is no different, in nature, to the carpenter, in this abstract, simplified economy. It provides a service, say maintaining a bridge that both the carpenter and the wood supplier cross regularly. To keep things simple, the bridge is made of wood, so each maintenance project begins with a trip to the wood merchant, and the same kind of transaction as that between the carpenter and the wood merchant takes place.

In order to repay the IOU, the government can impose a toll. So each time the merchant or the carpenter cross it, they hand out and IOU that they have collected through previous transactions. Or, the government can simply force the merchant and the supplier to hand in a predefined amount or % of IOU’s, called a tax, at a given time, say April 15.

Each of the merchant, supplier and government spends before collecting receipts. There is nothing special about government spending first as claimed by MMT.

If one party does not deliver on its promise to repay his IOU, the system breaks down (of course in the actual world, there is some room for error). Yet, that is the exactly the opposite of what MMT implies, in treating the CB’s liabilities as net financial assets to the system.

I’m still hopeful someone will help me put an economic explanation on net financial assets.

The government has a significant role to play, even this simplified economy, that we can relate to in the real one:

Let’s say the carpenter does not do his job, not because he is lazy, but because of the lack of demand. The government can step in and ask him to build a storage facility, that although needed by both the carpenter and the merchant, is too much too afford for them to afford. Ultimately, the consequence of that decision falls back on the merchant and the carpenter : if the government was right, the storage facility will generate growth in the short term, and in the long term through a more efficient economy. Sure the government will collect more taxes, to repay for the storage, but overall it will seem like a bargain. Conversely, if the government was wrong about the need for a storage facility, it will be a loss to the system.

The reason that the gov is able to take a longer perspective than either the merchant and the carpenter is a matter of trust/privilege. There are institutions and laws to make it look that way. The free lunch implied by NFA, however, needs in my view to be argued further, as otherwise, it may seem like a bit of an artifact.

Marshall,

I am quite empathetic to Anon’s points. Hopefully he/she sees this post soon. I am sure Anon knows all the monetary operations and sequences of transactions well.

I won’t try to put across what he/she wants to say. I have done so a couple of times well but in another occasion I was told by Anon that I “should have discerned that my theme is larger than what you’ve attributed there.” 🙂

I particularly liked this point

and

In other words, in my interpretation, bond investors can refuse to purchase US Bonds. Also the US is a special case where the probability of this event is minute, but it can happen in some other country if they have a no overdraft rule.

Now, some of my comments have been to bring in the platinum coin issuing ability of the US Treasury – effectively making the overdraft meaningless but that is comparable to the “extraordinary evasive action”. Plus recently they did manage to put up an evasive action of a modest size and it doesn’t really matter if the Euro Zone governments are currency creators. What is borrowed by the Special Purpose Entity will be replenished by government spending – with a bit of involvement from the ECB to smooth out the operation. There is still a possibility for the Euro Zone to go on. There will be austerity but thats the case even in the US. They EZ governments continued to borrow all these years at a yield no different from each other and I guess if somehow the crisis is resolved in the EZ because of some complex set of positive events, they may again get the opportunity ?

The other thing I wished to bring in was the current account deficits but Anon seems less worried about it, at this point.

Ramanan,

I’m still waiting for a fact or fiction on my point. If fact, then you have your difference b/n govt and other sectors. If fiction, I’d like to know how.

Also, Ramanan,

No MMT’er has ever said anything as silly as “bond holders can’t refuse Tsy’s.” The issue is, at what price will they purchase them? If you have a disagreement with ESM’s view as described on Warren’s site, which is the general MMT view assuming no CB intervention either in bond markets or via overdrafts, then I’d like to see that spelled out. And we’ve already explained several times why there is a difference between that and at what prices, say, US state or EZ bonds are purchased. But Anon doesn’t think that issue’s relevant, apparently, or doesn’t think it’s worth discussing, or at least hasn’t discussed it.

Scott,

I will wait for Anon to say fact or fiction. As far as I am concerned, yes what you have mentioned in your comment @3:37 is FACT. In fact I have an example of it from a recent event in India. It becomes news in the financial media in India, because the Reserve Bank of India doesn’t seem to understand the system well. That is good for me – in fact when it happened (due to tax payments), some 14 months back, it was the reason I landed in this blog and got interested in Macroeconomics from the right places. Fortunately, I had never learned neoclassical stuff. This is the article on the 3G auction and reserves impact.

WRAPUP 2-India telcos raise 3G funds, cbank assures on liquidity

Such events speak for themselves that the central bank and the government are no so independent as mainstream says . My point however, is that in the present system it doesn’t really matter if the government runs its finances from a bank account. In that case, one can’t ask “where do the reserves come from to borrow first?” because the government finances are not in HPM. The important point Anon is making is that bond purchases are volitional instead of non-volitional and if the purchaser is not going to buy, there is a contingency operation that is needed to be carried out and the recent events in the Euro Zone show that there are “contingency” operations possible there as well. The point Anon is making is that there is nothing automatic in the present system in the US where contingency operation is not required with probabilty 1. Also, I only recently learned the special powers of the Treasury which was pointed out by the commenter Beowulf, and I think its important. In the MMT proposed system however, there is of course no need for these things. However Anon may have issues with banks’ balance sheet, which I may also think about and ask sometime.

“The important point Anon is making is that bond purchases are volitional instead of non-volitional and if the purchaser is not going to buy, there is a contingency operation that is needed to be carried out and the recent events in the Euro Zone show that there are “contingency” operations possible there as well. ”

Agreed with the point, though I don’t know for sure if that’s Anon’s point or not. Like you, every time I try to summarize the point, I’m told I’m not getting it. If that is the point, I fail to see how there’s anything original there that MMT hasn’t recognized over and over again. I would imagine browsing this site over the past year would find that Bill has said that probably 10 times or more.

Bx12:

Actually, the carpenter had to issue the IOU prior to spending – he needed to find a willing wood merchant to provide him the wood in exchange for a promise to pay before he could spend the wood.

Of course, the carpenter has to spend (invest) prior to future income, but that is a physics constraint – time only moves in one direction – not a financial operational constraint. The operational constraint for the carpenter is that he must borrow prior to his spending (investing) and his borrowing creates an obligation to another party.

Lets assume the carpenter is successful and produces something of value – there is now more real stuff (something fulfilling real demand by others) than before he took out his wood loan.

So, how how is this reflected financially? Financial medium serves two purposes – to facilitate exchange and to represent value. Lets say at some point the carpenter’s thing generates sufficient income to pay off the wood merchant. So, the carpenter now owns his thing free-and-clear. How do we represent this financially?

If the only source of financial media is via private obligations – you cannot represent new financial wealth with any stability (an assertion). If the economy grows and creates new stuff, then either there needs to be an external source of providing financial representation, or the private financial sector will gain an increasing proportion of total wealth – because they must issue financial media with corresponding obligations. In which case, if the carpenter is to own his thing free-and-clear, then the net effect in the economy must be more private obligations to back private issuance of financial medium (or a net contraction of financial medium).

One alternative to this would be to allow the private sector to issue financial media without obligations – but why would a private entity do this? Only if the liability they issued was not theirs – kind of like Citicorp printing notes that are redeemable only at Bank of America without BoA’s knowledge. Or, in the good old days of the US, a private bank issuing their own notes to their directors to serve as their paid in capital (it would have been a lot of fun to be a US banker in the 1800s).