I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Employment gaps – a failure of political leadership

Overnight a kind soul (thanks M) sent me the latest Goldman Sachs US Economist Analysis (Issue 10/27, July 9, 2010) written by their chief economist Jan Hatzius. Unfortunately it is a subscription-based document and so I cannot link to it. It presents a very interesting analysis of the current situation in the US economy, using the sectoral balances framework, which is often deployed in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). While it relates to the US economy, the principles established apply to any sovereign nation (in the currency sense) and demonstrate that some of the top players in the financial markets have a good understanding of the essentials of MMT. But the bottom line of the paper is that the US is likely to have to endure on-going and massive employment gaps (below potential) for years because the US government is failing to exercise leadership. The paper recognises the need for an expansion of fiscal policy of at least 3 per cent of GDP but concludes that the ill-informed US public (about deficits) are allowing the deficit terrorists to bully the politicians into cutting the deficit. The costs of this folly will be enormous.

The GS briefing is entitled – Why Is the Economy So Weak? What Can Policy Do? and examines:

… two of the most basic questions about the economic outlook in the context of a “financial balances” framework. First, why have US growth and employment been so weak since 2007? And second, what can policymakers do about it?

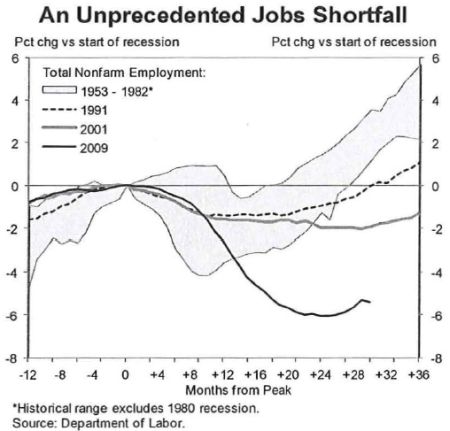

They begin by emphasising the “unprecedented jobs shortfall”. So for those who consider that employment should not be a central concern of the policy debate or that Americans do not think employment is an issue at present at least the economists at GS would disagree.

By motivating their discussion with a very scary presentation on how far the US labour market is from its past performance levels in terms of employment growth, the GS economists are clearly indicating that they consider the lack of jobs to be a central policy issue.

They present this graph (reproduced from their paper) to show the jobs shortfall.

The graph shows:

… the extent to which the recent recession and its aftermath have diverged from postwar experience by plotting the level of nonfarm payroll employment against prior postwar cycles, starting from the peak of the business cycle (i.e. the start of the recession). Relative to the start of the recession, the level of employment payrolls is now about 8% lower than in the median cycle of the 1954-1982 period. Scaled to the current level of the labor force, this is a shortfall of roughly 10 million jobs.

So when you read about the historically high budget deficits (as if they matter per se. Not!) the magnitudes involved shouldn’t surprise you given how great the plunge in employment has been in the US in this recession.

As the GS paper says – there is an unprecedented jobs shortfall.

The latter takes taxpayers out of the picture and via the automatic stabilisers drives the deficit up. The real problem is the employment shortfall which is stark and reflects a monumental failure of policy.

They note that this has been an “unusually deep recession and an unusually weak recovery”, which have combined to create this unprecendented jobs gap. In saying this they reject the views of many mainstream economists who believed that there would be a V-shaped recovery even without government fiscal support. Implied, is a rejection of austerity approaches which are now gaining favour among policy makers across the world.

The GS paper says:

The sheer size of this gap suggests strongly that the cycle is fundamentally different from its postwar predecessors … at the most basic level, we view the distinguishing feature of the current cycle as a collective attempt by the different sectors of the economy-households, firms, governments, and the rest of the world-to reduce their debt loads by pushing spending below income. This does not mean that every sector is trying to run a surplus – as is well known, the US federal government is currently running a large deficit and planning to do so for many years. But it means that those sectors that are running deficits are moving less aggressively than those that are running surpluses. This implies a demand shortfall for the economy as a whole.

This is a very meaningful statement. It draws on the sectoral balances framework and interprets outcomes within that framework to the state of aggregate demand (spending) overall.

To refresh your memory (again, sorry! – skip through this if you know it by heart), the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

The GS Paper says that:

Since the three sectors constitute a closed system, one sector’s borrowing must always be another sector’s lending. Hence, the three sectoral balances must sum

to zero …private balance + public balance = CA balance.

So they are writing the identity as (S – I) + (T – G) = (X – M). It doesn’t matter how you express it as long as you know what a deficit or surplus balance means.

From my derivation, we can also simplify the balances by adding (I – S) + (X – M) to get the non-government sector balance. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

So when the government runs a surplus, the non-government sector has to be in deficit and vice-versa. There are distributional possibilities between the foreign and domestic components of the non-government sector but overall that sector’s outcome is the mirror image of the government balance.

To say that the government sector should be in surplus is to also aspire for the non-government sector to be in deficit. if the foreign sector is in deficit the national accounting relations mean that a government surplus will always be reflected in a private domestic deficit.

In many nations, the pursuit of government surpluses squeezed the private domestic sector of liquidity. This proved to be an non-viable growth strategy because the private sector (which always faces a financing constraint) cannot run on-going deficits. Ultimately, the fiscal drag coming from the budget surpluses (structural or otherwise) forces the economy into recession (as private sector agents restructure their balance sheets by saving again).

At that point, the budget will typically move back in deficit via automatic stabilisers (if the external balance is is deficit).

Further, given the non-government sector will typically desire to net save overall in the currency of issue, a sovereign government has to run deficits more or less on a continuous basis. The size of those deficts will relate back to the pursuit of public purpose.

But you can see how an aggregate demand shortfall can occur. The government deficit has to be sufficient to support the desired non-goverment surplus.

Given that the sectoral balances are an accounting statement and they have to sum to zero at all times what sense is there to the statement that the government deficit might be insufficient to support the desired non-goverment surplus?

To answer this query we use the distinction between ex post (after the fact) outcomes and ex ante (desired or planned outcomes). This distinction is commonly used by economists.

As the GS paper notes the sectoral balances “must always hold ex post as a matter of accounting” but “need not hold ex ante”. So:

… it is quite possible for different sectors to pursue spending plans that are mutually inconsistent with one another, and such inconsistencies can keep aggregate demand away from the economy’s supply potential. In general, if all sectors taken together aim to run a financial deficit – i.e. want to spend more than their expected income and want to finance the difference by borrowing – the economy will tend to overheat. Conversely, if all sectors taken together aim to run a financial surplus – i.e. want to spend less than their expected income and use the difference to pay down debt – the economy will tend to operate below potential.

So our desires or plans motivate behaviour which then manifests as spending decisions and outcomes. Ultimately, once these decisions are implemented the sectoral balances accounting will generate the ex post zero sum of the balances. But this outcome doesn’t have to deliver desirable economic outcomes and some sectors may be unable to achieve their desired outcomes because of income adjustments in response to aggregate demand variations.

Thus, if there is a current account deficit, and both the government and private domestic sectors implement plans to generate surpluses there will be shortfall in aggregate demand which will generate cuts in output and income. These income shifts drive the budget towards or into deficit and stifle the private sector plans to save. So eventually the actual balances add to zero but neither the government or the domestic private sector will be achieving their plans.

That is the difference between the ex post and ex ante perspectives. The latter tells you about the behavioural motivations and direction of spending while the former tells you what happens after the income adjustments have taken place.

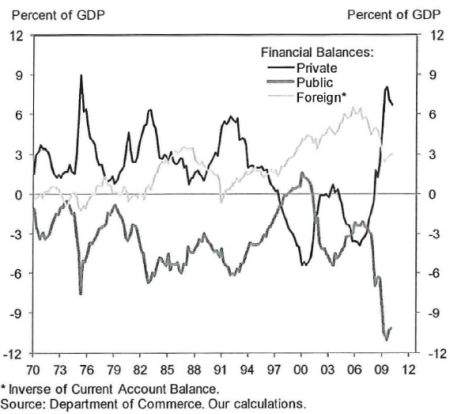

The following graph shows the ex post sectoral balances for the US and is reproduced from the GS Report (Exhibit 2). The chart carried the title “Private Sector Surplus Offsets Public Sector Deficit”:

The dramatic reversal in the private balance (into surplus) reflects the reaction to the private debt-binge in the period leading up to the crisis. During that period the mainstream economists were all applauding the “financialisation” of the economy and declared the business cycle was dead. Please see my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for an account of this failing.

But the collapse in aggregate demand which has generated the “unprecendented jobs shortfall” was brought about by the private desire to reduce their debt-exposed positions. The only way that can occur is for the sector is to shift back into surplus overall and start paying down the debt in net terms.

The GS paper says:

… the current configuration of the three balances. As of the first quarter of 20 I0, the private sector was running a 7% of GDP surplus, the public sector a 10% of GDP deficit, and the rest of the world a 3% of GDP surplus vis-a-vis the United States.

You can also see the Clinton surpluses were only made possible by the growth generated by the private sector going into significant deficit (which also pushed the current account further into deficit). The automatic stabilisers in the early Bush years wiped out those surpluses very quickly as the US economy went into recession.

The GS paper then considers the future. For simplicity, they “assume that the current account is fixed at a deficit of 3% of GDP”. They then invoke politicial (not financial) constraints on the size of the public deficit. They say:

we assume that the public is uncomfortable Congress believes that the public is uncomfortable – whenever the general government deficit is above 7% of GDP. While larger deficits are possible for short periods of time, Congress ultimately responds to them by cutting spending and/or raising taxes. The precise number is obviously arbitrary, but we do believe that there is a level of government deficits beyond which the political demands for retrenchment become difficult to resist.

So note they are not invoking a financial argument here. They realise that a sovereign government such as the US is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency.

These political constraints are reinforced daily by the relentless media attack on the deficits.

While the opinion polls suggest people don’t like deficits I think if there was a poll asking people to define a deficit correctly there would be an inverse result. Most people I talk to of lay status do not understand what a deficit is although they are not short of an opinion about them.

I see a major role for progressive leadership in this regard. The conservative think tanks are expert at scaring the britches of everyone knowing that the trouserless haven’t much idea of what they are scared of. The progressive side of the debate has fallen down badly in countering the mis-information both because it lacks financial support of the likes of Peter G. Peterson and because most progressives do not understand how the monetary system operates anyway.

But a political constraint is something that can be removed over time by appropriate education and activism. That is the challenge on our side of the debate. We are losing badly though.

Anyway, putting the two assumptions together (3 per cent external deficit and 7 per cent budget deficit), the GS paper concludes that:

These assumptions imply that the private sector cannot aim to run a financial surplus of more than 4% of GDP without sapping aggregate demand. This is a serious problem because our analysis a few weeks ago concluded that the private sector may target a financial surplus of significantly more than 4% of GDP for the next few years in order to reduce its debt burden at an acceptable pace.

The GS paper predicts that the private surplus will have to be around 7 per cent of GDP for several years, that is, “large surpluses are likely to be necessary in order to bring the private debt/GDP ratio back to historically more normal levels.”

You can then do the sums. If the private sector continues to push towards this overall desired surplus and the political situation forces the US government to contract their fiscal position, then on an ex ante basis there will be a shortfall of spending and income by at least 3 per cent. The GS paper concludes that:

This demand shortfall saps production, and consequently the income from production. As a result, private sector income is lower than expected, which pushes the private sector balance below 7% of GDP (i.e. to a “looser” position than desired by the private sector) unless there is a further downward adjustment in private sector spending. Moreover, lower private sector income implies lower tax revenues, which has a similar impact on the government balance and could trigger further austerity moves by Congress. Ultimately, this adverse feedback loop doesn’t end until someone accepts a smaller surplus or a larger deficit.

In other words, the political constraint that the US government has accepted after all the goading of the deficit terrorists not only damages the private sector (leaving it more indebted than it desires to be) but also creates bad deficits and an even larger jobs shortfall.

An education campaign is required by governments around the world to elucidate their constituencies about the damage that the terrorists are causing.

The other point is that the deficit rises anyway – and you have only dread to show for it.

The GS paper then asks “What can policymakers do?” They conclude that:

In the context of the financial balances framework, the most straightforward response is to boost aggregate demand by targeting a government deficit of at least 10% of GDP – indeed, a bigger target would be better because a period of sharply above – trend growth would be highly desirable to fill in the economy’s large output gap.

For aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal the total income generated in production (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not in each period).

Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages). Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account through the offer of labour but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal.

As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment.

MMT then concludes that mass unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low.

To recap: The purpose of State Money is to facilitate the movement of real goods and services from the non-government (largely private) sector to the government (public) domain.

Government achieves this transfer by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue.

To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed.

The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets).

It is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and the non-government sector’s desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In MMT, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending (saving) decisions in force at any particular time.

Shift in private spending certainly lead to job losses but the persistent of these job losses is all down to inadequate net government spending.

Thus, decisions by the non-government sector to increase its saving will reduce aggregate demand and the multiplier effects will reduce GDP. If nothing else happens to offset that development, then the automatic stabilisers will increase the budget deficit (or reduce the budget surplus).

If the government may decide to expand its discretionary spending and/or cut taxes this will add to aggregate demand and increase GDP. The deficit will increase by some amount less than the discretionary policy expansion because the automatic stabilisers will offset that increase to some extent. But the non-government sector will also enjoy the increased income and this allows them to increase total saving.

In general, if the private sector desires to increase its saving, the role of the government is to match that to ensure that the income adjustment will not occur – with the concomitant employment losses etc. In that sense, fiscal policy has to be reacting to private spending and saving decisions (once a private-public mix is politically determined).

Please read my blog – Deficits are our saving – for more discussion on this point.

The GS paper argues that:

The main objection to such a policy is that higher public deficits raise the risks of a public debt crisis of confidence. Our own view is that these risks have been exaggerated, at least in the case of the United States. Public debt and especially public debt service are still at moderate levels, and the bond market is showing few signs of discomfort with the US fiscal outlook. Moreover, as a practical matter it is in any case difficult to avoid large deficits as long as the private sector is retrenching and the current account is in deficit. As already noted, this saps revenue growth. So it is better to accept the need for these deficits on an ex ante basis since, to a large extent, they will happen ex post anyway.

In other words, there is no solvency risk. There will be budget deficits anyway. And it is better to fill the spending gap and generate employment growth.

The conservatives and the deficit terrorists simply fail to comprehend the points being made here. They think that the government can reduce debt by running surpluses at the same time the private sector is reducing debt by running surpluses in an environment where the external balance is in deficit. Those desired aims are impossible to achieve.

If the respective sectors try to enforce these aims, the income adjustments will be severely negative and the ex post outcomes will negate the intended outcomes.

Why the US government is not running coast-to-coast advertisements about this is beyond me.

The GS paper says that the current situation is that policy that “may be sensible economically but unrealistic politically” is being hindered. They conclude that:

The upshot of our discussion: given the forces of retrenchment and balance sheet repair, the risks to the growth of aggregate demand-as well as risk-free interest rates—over the medium term are tilted to the downside. Policymakers can provide some relief, but realistically will find it hard to neutralize the headwinds altogether. Thus, the risks to growth over the medium term are clearly tilted to the downside.

Conclusion

So we have a situation where the US is likely to have to endure on-going and massive employment gaps (below potential) for years because the US government is failing to exercise leadership.

It is clear that there is an urgent need for an expansion of fiscal policy of at least 3 per cent of GDP. But given the appalling state of politics in the US that is unlikely to happen.

So the US public is going to suffer for their ignorance at the hands of those who will continue making money and accumulating wealth but who are most vocal in the call for fiscal austerity.

In some future time, we will be invaded by another planet and they will conclude we were a really stupid race of people.

That is enough for today!

The US is running record deficits and and another $35 billion alone was added just yesterday. The problem is that the money not getting down to the levels where it’s needed to create employment via bank lending. Banks and companies are hoarding cash at a record rate. Take a look at Alcoa; their CapEx is the lowest in years yet everyone cheered the great result – we know where that came from. Economic theory is great but the reality is somewhat different when human actions can not be explained by mathematical equations. The failure is with the US political system, not the fact that there is an insufficient money supply.

Glen: You assume that once banks start lending, suddenly companies will borrow and start hiring people. What’s more likely is that companies don’t want to risk overproducing if no one is buying their goods – no matter how many loans they have. After all – what makes a company feel more secure in their finances: loans, or cash from sales?

It’s not necessarily that there’s not enough money – it’s that the money that there is currently sits in bank reserves doing nothing but earning interest instead of circulating and boosting demand.

“Economic theory is great but the reality is somewhat different when human actions can not be explained by mathematical equations”

That’s fine, but sectoral balances will hold no matter what humans do. That’s the point – they force the overall situation regardless of individual choices. Households can exercise their wonderful, non-mathematical free will all they want, but they are still revenue constrained and thus subject to basic accountancy.

Glen: “The problem is that the money not getting down to the levels where it’s needed to create employment via bank lending.”

I think that the money should get down to where it creates employment via customer spending. The bank lending will follow.

“The paper recognises the need for an expansion of fiscal policy of at least 3 per cent of GDP but concludes that the ill-informed US public (about deficits) are allowing the deficit terrorists to bully the politicians into cutting the deficit.”

No, I don’t think so. When people in the USA talk about gov’t deficits, at least 99% of them mean more gov’t debt. There are people who realize this debt will mean an increase in taxes (like all the talk about a VAT) and/or cutting SS, Medicare, and Medicaid. This is exactly what the spoiled and rich domestics and foreigners (the “friends” of goldman) want. They want to “steal” the real earnings growth and retirement of the lower and middle class.

“First, why have US growth and employment been so weak since 2007?”

How about positive productivity growth and cheap labor from free trade, legal immigration, and illegal immigration along with some asset bubbles to mask it earlier?

“The sheer size of this gap suggests strongly that the cycle is fundamentally different from its postwar predecessors”

How about the world has gone from supply constrained to demand constrained or pretty close to it? And, by demand constrained I do NOT mean because there is not enough debt on the lower and middle class in the high wage countries.

“we view the distinguishing feature of the current cycle as a collective attempt by the different sectors of the economy-households, firms, governments, and the rest of the world-to reduce their debt loads by pushing spending below income.”

How about breaking down that household sector into the spoiled and rich (especially and including those at goldman) and the lower and middle class?

Anybody at goldman trying to reduce their spending below income? Anybody there trying to reduce their debt load? I doubt it because they have so much unworthy income to begin with and probably no debt loads.

just an fyi, I recall Wynne Godley worked with the Goldman econ group for a while.

“There are distributional possibilities between the foreign and domestic components of the non-government sector but overall that sector’s outcome is the mirror image of the government balance.”

Yes there are!!! How about concentrating on the spoiled and rich “excess savers” that won’t retire or it makes no sense for that excess saving entity to retire.

“While the opinion polls suggest people don’t like deficits I think if there was a poll asking people to define a deficit correctly there would be an inverse result. Most people I talk to of lay status do not understand what a deficit is although they are not short of an opinion about them.”

Ask them about a “deficit” funded with currency (no interest payments and no POSSIBILITY of repayment due to rollover problems of the debt) and a “deficit” funded with debt.

“This demand shortfall saps production, and consequently the income from production.”

Will companies react by lowering supply to maintain pricing and therefore lower real GDP (or maybe its potential)? Would that make interest payments on the debt harder to achieve?

Very positive news! Optimist about MMT popularization!

“Ultimately, this adverse feedback loop doesn’t end until someone accepts a smaller surplus or a larger deficit.”

How about “ultimately, this adverse feedback loop (DUE TO TIME DISTORTIONS between spending and earning that debt can create between the major groups, which are the lower and middle class; the spoiled and the rich; and the gov’t) doesn’t end until someone accepts a smaller surplus or a larger deficit?

Most people I talk to of lay status do not understand what a deficit is although they are not short of an opinion about them.

I find this incredible. How can anyone who’s made it through, say, the eighth grade, not understand what a deficit is? What sort of misconceptions are you encountering?

I find it easy to believe that they don’t understand the implications of a government deficit.

Ken

Beyond time for me to shut up for awhile.

Dear Ken

You said:

1. They don’t know the difference between a stock and a flow.

2. They don’t know that the accumulated deficits are a record of their saving in the currency of issue.

3. They don’t know that deficits add income to the private sector.

4. They don’t know that surpluses destroy private income and force them to liquidate their wealth.

5. They don’t know that deficits do not equal as a matter of financial necessity public debt.

6. They don’t know that the government has a choice about issuing debt or not.

7. They think their taxation is required to support the net public spending.

All obvious misconceptions that lead to erroneous conclusions about the need for more fiscal support (or less in other situations).

best wishes

bill

Thanks …. I buy them not understanding those things. Those are all implications of deficits, about which I agree even highly educated people are hopelessly confused.

Ken

I’m with rvm here, great news! Having reaped the benefits of a cyclical inventory recovery and sitting on mountains of profits, western corporations are looking into the future and seeing they are but a few steps from the demand precipice with a complete void beyond. They are rediscovering after 80 years that commerce is liberal!

And if Goldman can finally see beyond the institutional habits of a gold standard now close to forty years in the grave, having glimpsed the abyss, as a matter of capital preservation they have every incentive to proselytize!

The conclusions of the paper are so profoundly at odds with the pervasive ideology that supports conventional US so called economic thinking that the authors assume a political paralysis will hold that could quickly melt.

In 1989 I was working for a very smart and educated refugee from East Germany, at the time 65 years old and out of East Germany since 1947. Not a month before the wall came down in Berlin he continued to insist it could not happen in his life time. I saw him last at our holiday party this winter and he’s doing great 21 years after the fall. Our politics has been overtaken by events entirely since 2008 and there is no reason to believe the hubris of those who think they are in control now any more than two years ago.

Neo-liberalism appears to be expanding and at a rate which may be detrimental to their future survivial. As they are not able to exercise moral restraint to reduce their own numbers to a satisfactory level we need to be proactive and introduce a culling program before it’s too late.

http://www.lecercledeseconomistes.asso.fr/spip.php?article318

Here’s some interesting proposals for Europe right now.

These are only recommendations, but they’re made, for one, by EADS and AXA CEO, so we can hope.

These two proposals were in an LeMonde article (it’s in french and you need membership)

–10% of GDP in eurobonds, targeted on infrastructures, research and development, the organization of higher education systems, as well as investment in growth enhancing sectors (energy, ITC, agri-food, water, transport, waste management, biotechnologies)

–reverse the SGP

and I can’t see them again in the final proposal but maybe this is the proposal 6 and 7.

It’s worth a look I think and I hope they’ll go this way and break with the austerity obsession.

Dear Bill, is it possible that GS analysis could be related to your participation in Boston workshop?

Heh, it almost sounds like GS’s chief economist has been reading billy blog. This is good news indeed. It also sounds like the report was written with the understanding that it would represent “new thinking” for most of its audience, and they would need to be brought up from first principles. I ‘spect that a lot of influential people read GS reports and take them seriously.

My own framing:

(1) Everyone’s income results from someone else’s spending (either govt or private).

(2) “Saving” means spending less than your income. If an equal number of people want to save as want to dis-save (spend more than they earn), things work fine. But right now most people want to save, to pay down their debts and improve their balance sheets. So there’s not enough spending, in aggregate, to support people’s desire for income, in aggregate.

(3) This can be resolved in one of three ways:

— Lower interest rates encourage people to borrow and spend (dis-saving). But the rate that the Fed uses is effectively at zero, and thus can’t be lowered. (Though I’ve seen increasing calls, including from Krugman, for the Fed to directly intervene in longer-term bond markets; I doubt it would be enough, but it seems worth doing)

— A larger govt deficit.

— Some people are forced into dis-saving when their incomes are eliminated by unemployment. If you unemploy enough people, force them to spend down their savings or go into debt to meet daily expenses, then eventually their involuntary dis-saving will offset the saving by those who still have jobs.

The conservatives and the deficit terrorists simply fail to comprehend the points being made here. They think that the government can reduce debt by running surpluses at the same time the private sector is reducing debt by running surpluses in an environment where the external balance is in deficit. Those desired aims are impossible to achieve.

The situation is just become much more complex in the US. Sen. Kyl, a key spokesman for the GOP leadership, wants an extension of the Bush tax cuts even though that would result in much larger deficits than the proposed increases in social spending (like extending unemployment benefits for the LT unemployed) would. He dismisses the notion that this deficit balloon resulting from tax reduction is a bad thing. I think that the political game has suddenly changed for people paying attention. It is pretty obvious that all the GOP fear-mongering over deficits is disingenuous. Deficits resulting from social spending, bad. Deficits resulting from tax cuts, good. This is ideology, pure and simple. The curtain has been drawn back.

Arthur Laffer, who is well versed in soft currency economics in addition to being a supply side guru, has been agitating for a deeper across the board tax cut lately, including the capital gains and inheritance. He argues that social spending doesn’t fix anything because it doesn’t add jobs. He argues for curtailing unemployment benefits, too, since he claims that they just encouraging idleness. Clearly, he is not concerned with deficits and also knows that they don’t matter.

For Republicans deficits become “strategic deficits.” The GOP uses them to argue for cuts in social spending and trimming government (but not military spending, which is off the table), because “we can’t afford it,” even though people like Laffer know full well that this is just BS. In fact, Both Stockman and Norquist have admitted that this is the strategy, so it is no secret. It is called “starve the beast.”

The conservative argument is that increased spending is needed to create demand but that government spending is inefficient. For them, efficient spending is investment that leads to job creation, income and consumer spending. Government just gets in the way of this “natural” process that would happen automatically if we just cut taxes, eliminated regulation, and let the invisible hand that guides the free market work. “Government has never created a single job.” The way to increase investment is to cut taxes, eliminate social spending (which is socialism), and gut regulation and oversight. For them, it’s as simple as that. But they conveniently don’t explain why Bush II cut taxes drastically and the number of jobs created during his eight year in office was the lowest in recent memory, or that the Bush years culminated in the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

Many are objecting hat over recent years US productive investment has not been in the US. The US manufacturing sector is declining as more and more US companies are building production facilities in Mexico and China to take advantage of lower worker compensation and laxer regulation, e.g., worker safety. Moreover, the wealthy and corporations are awash with cash and not investing, so they don’t need tax breaks and subsidies.They aren’t investing because they don’t see good investment opportunities in the US, even with very low rates prevailing.

I’m not sure that “educating the public” is a viable option for change. See How Facts Backfire in the Boston Globe.

It turns out that many people harden their position in the face of contrary facts. This applies especially to those holding conservative views, but to others as well. I think I have reported here several times on progressive opposition to MMT when I posted on various progressive blogs. Reasoning based on fact, equations, and operational reality didn’t get very far with them and was rejected out of hand. When I first encountered this, I was shocked. No more.

“Heh, it almost sounds like GS’s chief economist has been reading billy blog. This is good news indeed. ”

No. He’s been reading and corresponding with Wynne Godley for at east 10 years. GS have been long time supporters of Wynne Godley. This has nothing at all to do with MMT and is not news.

“Dear Bill, is it possible that GS analysis could be related to your participation in Boston workshop?”

The GS analysis is based on Jan Hatzius’s long relationship with Wynne Godley, and his involvement with the Levy Institute where he has attended the Minsky Conference and presented with Rob Parentaeu, who is also an avid Godley reader.

Warren Mosler is right to point that out

Dear Bill,

Just wondering if anyone would have an explanation:

“[Over the past 3 years and 9 months, the US has accumulated an incremental $4.7 trillion in new debt, even as the budget deficit has grown by “only” $3.2 trillion”].

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/june-deficit-fails-account-142-billion-excess-june-borrowings-us-has-issued-15-trillion-exce

jrbarch

jrbarch, yes, China etc. Do not forget current account deficit which is recycled into treasuries to large extent. Be it directly by China itself or indirectly by banks.

jrbarch,

I think ZH is not looking at growth in public debt over this period.

Here is DTS from Oct 06.

Here is DTS from June 10.

Table III-C shows total debt held by public increasing by 3.75T over this period. Not 4.7T.

The budget deficit tracks actual govt sector deposits minus withdrawls from the Treasury’s account at the Fed. The total Treasury Security issuance includes intra-govt sector issues (ie the govt sector “borrowing” from itself, an accounting exercise) so that number is often in excess of the actual govt sector deficit (G-T).

ZH tends to the sensational. Ive given up posting comments over there like this one as it doesnt go anywhere. Suggest you stay with billyblog!

Resp,

>Bill Mitchell says: “While the opinion polls suggest people don’t like deficits I think if there was a poll asking people to define a deficit correctly there would be an inverse result. Most people I talk to of lay status do not understand what a deficit is although they are not short of an opinion about them.”

> Tom Hickey says: “I’m not sure that “educating the public” is a viable option for change. See How Facts Backfire in the Boston Globe.”

I have been trying to read blogs and books and understand MMT, and this blog, of course, has been very helpful. But in my little nonprofit I run up against the same barriers talked about in the article Tom pointed to (and others).

So if I am trying to help my own understanding and spread the word, does anyone have a 3-page synopsis of what someone of “lay status” people needs to know? Remember, these people are schooled in the United States and with a far different understanding of how money works , and when you tell them people work so they can pay taxes to the government, their mind is going to snap shut with a loud “bang”. Not that it’s wrong, obviously, but there has to be a way to get to that in another manner.

What can help me understand the parts of MMT, the deficit, those things that you think they need to know, and get it across to the guy or gal who works every day and has a limited amount of time to learn. It is important that they have another source other than the things they get bombarded with each day, because while they may or may not understand MMT at the level people here do, they do have a vote, which can make all this work hopeless.

One of the things they do not cover in that article is how an influential center, someone the person respects, someone in authority, etc, has a better chance of getting past the natural obstacles. Which is why nonprofits look for advocates in a lot of places..

thanks

@Sergei

OFF Topic: You are living in Austria. So you might want to add another blog to your reading list? http://www.weissgarnix.de/ The author is a natural born Austrian living in Germany (like me 😉 and just announced Bill’s Blog to be one of his all-time favorites. He’s now featuring some Bilbo entries with a special Austrian rhetorical spin. (With spin I’m not referring to our “Austrian Economics” friends.) Stephan

I agree with Matt. The people who raise such questions have some vested interests.

The US Treasury has been transparent for long and people watch the auctions closely. It is extremely difficult and in fact impossible to cheat the public on such numbers. Go to the US Treasury website and look at the auction details to see the level of transparency.

Student, I would start with Warren Mosler’s The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds, which has recently been published in print.

Download a PDF here:

http://moslereconomics.com/2009/12/10/7-deadly-innocent-frauds/

It is short and written very simply, It debunks the myths that are obscuring the facts in a way that almost anyone can get if they are open to hearing it.

Nitpick on research reported in Boston Globe:

“He asked one group of participants what percentage of its budget they believed the federal government spent on welfare, and what percentage they believed the government should spend. Another group was given the same questions, but the second group was immediately told the correct percentage the government spends on welfare (1 percent). They were then asked, with that in mind, what the government should spend. Regardless of how wrong they had been before receiving the information, the second group indeed adjusted their answer to reflect the correct fact.”

As the lawyers say, assumes facts not in evidence. The second group’s (average?) answer was different, but there is no evidence of what their answer was before they heard the correct percentage. (Assuming the experimental procedure is correctly reported.)

student: “So if I am trying to help my own understanding and spread the word, does anyone have a 3-page synopsis of what someone of “lay status” people needs to know?”

Well, this is only my opinion as an American citizen. I think that right now what people need to know is what they are being told is false about the debt and deficit. I also think that they need to be told about how these falsehoods play into the “starve the beast” strategy.

Speaking for myself, as a child I got a pretty good idea about how the gov’t creates money. They print it. Now, I know that MMTers object to the term as inaccurate, but it is closer to the truth than the idea that the gov’t gets its money from the bond traders and taxpayers. So, basic fact #1 that I think that people need to know is this:

The gov’t is the ultimate source of the country’s money.

With educated people you have to get into money created by private banks, and its ultimate fragility, but I suspect that most people as children believed as I did, and you can tap that childhood belief.

Other facts follow from that:

The gov’t cannot run out of money. It is not at the mercy of bond vigilantes. There is no day of reckoning when the debt has to be paid off.

(This is taking longer than I intended, so I’l just mention some other facts that I think are important for people to know now.)

Deficits are necessary if people are to save or to pay down their personal debt. People who are crying that we should get our personal debt under control should be calling for higher deficits.

The Federal debt is not a burden, now or in the future.

Social Security is neither broke nor broken.

Our main problem now is unemployment, and we certainly can afford to bring it down, and bring it down quickly.

Note to myself about the research: I see that “immediately” is ambiguous. Was that immediately after answering the first question, or immediately after answering both? If the latter, my objection is moot. Sorry about going off topic like that.

Dear Sergei, Matt Franko, Ramanan,

Thanks for your clarifications – am a lay reader and shall stick to billy blog as advised. At least Bill offers answers rather than questions!! One more thing that is puzzling me if anyone could help: reading Michael Hudons latest article Dollar Hegemony and the Rise of China I didn’t see any real symbiosis to MMT, but thought what he was saying feasible. Where does Hudson fit in MMT’s picture – where does MMT fit in Hudson’s picture – that is, how do both fit in relation to each other in the macroeconomic picture?

Cheers,

jrbarch

Thank you Min

And I will work in the points Bill mentioned in “the things people don’t know”.

It’s funny – other points of view are all over the airwaves, yet one has to go hunting for this stuff. And when you tell them things like the deficit doesn’t matter like they think it does, they immediately make the error of comparing it with their own personal “economy”, and telling them that Social Security is not broke really sets them off, ’cause that’s all they hear. But when I approach it as “this is your money, you worked for it, it is held to pay you when you can’t help your self as easily – and people are trying to steal it from you” – they pay attention. 😉 So there are ways to wiggle into those thoughts.

I wonder what people who really want to get the point across would do with 10 mniutes on Oprah….cause the other viewpoints are getting that much exposure 50 times a day.

I am looking forward to any other thoughts…

The situation regarding US government debt (public or intra) is not that clear.

Here one can find historical deficits http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals/

Here is Treasury debt stats: http://www.treasurydirect.gov/NP/BPDLogin?application=np

So regardless how you measure historical deficits do not sump up to any debt number with difference being at least 1 trln.

@Stephan: thnx for the link. Will be easier to distribute around while mentioning that this guy is Austrian by passport and not persuasion 🙂