Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – March 13, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

From the US National Accounts, you find that in 2006, the share of Personal consumption expenditure in real GDP was 69.9 per cent and by 2008 it had fallen to 69.8 per cent. Similarly, the share of Gross private domestic investment on real GDP was 17.2 per cent in 2006 and by 2008 had fallen to 14.9 per cent (and further to 11.8 per cent in 2009). The net export deficit over the same period (2006 to 2008) fell from -5.7 per cent of real GDP to -4.9 per cent in 2008. Finally, the share of Government consumption expenditures and gross investment in real GDP rose from 18.8 per cent in 2006 to 18.9 per cent in 2008 (and 19.7 per cent in 2009). These relative changes tell you that real GDP was lower in 2008 compared to 2006 because the increase in Government spending and the falling negative contribution of net exports were not sufficient to offset the declining contribution from consumption and investment.

The answer is False.

The detail in the question relates to expenditure shares in real GDP and clearly does not tell you anything about the growth in GDP. All that you are being told are that the shares are changing over the period 2006 to 2008 in favour of public spending.

The shares are given by the following equation:

where A(t) is the value of aggregate A in quarter under consideration (say Personal consumption expenditure) and GDP(t) is the value of GDP in the same quarter.

So a change in the public spending share from 18.8 per cent in 2006 to 18.9 per cent in 2008 just says that in 2008 the flow of public spending is a greater proportion of the flow of real output in 2008 than it was in 2006. The rising share could be associated with a declining, constant or growing real GDP.

The fact you know that over this time that real GDP growth in the US was falling is irrelevant – the question asks whether you can conclude from the information before you.

The other related measure is the contributions to GDP growth which tell you each quarter what the expenditure components contributed to the GDP growth in that quarter.

From the Australian National Accounts – December 2009 you can find the definition of the contributions to GDP growth which is represented by the following equation:

where A(t) is as before; A(t-1) – value of aggregate A in previous quarter; and GDP(t-1) – value of GDP in previous quarter.

The ABS indicate that “the contributions to growth of the components of GDP do not always add exactly to the growth in GDP. This can happen as a result of rounding and the lack of additivity of the chain volume estimates prior to the latest complete financial year.

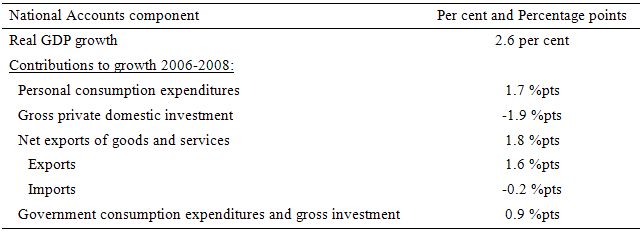

From the US National Accounts data you see that real GDP grew in 2005-06 by 2.7 per cent; then slowed to 2.1 per cent in 2006-07, 0.4 per cent in 2007-08 and plunged to -2.4 per cent in 2008-09. Over the period 2006-2008, real GDP grew overall by 2.6 per cent. The following table breaks down the contributions to that growth by the individual spending components (computed as per the Equation above).

The point of the question (if any) is to warn you into being careful to clarify the concepts being used before drawing conclusions. Too many people think they know what these terms mean and either mis-use them themselves to reach erroneous conclusions or allow themselves to be fooled by others who are touting erroneous conclusions.

If you are interested in more detail on national accounts then the 5216.0 – Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods, 2000 – is the place to go. Recommended reading if you want to get all the concepts and stock-flow relationships really sorted out. The system is universal and used by all statistical agencies.

Question 2:

The US Senate has recently debated whether to extend unemployment benefits given the lack of job opportunities currently available. One side of the debate says the proposal will reduce growth because it reduces the incentive to search for work although the evidence for this impact is weak. The other side of the debate says the proposal will maintain and perhaps stimulate growth because it will maintain spending capacity of those without work. Even if the former effect was strong, the proposal would not harm growth at present.

The answer is True.

The clue to the answer was in the last two words of the question at present.

First, the proposition that unemployment benefits reduces the incentive to search and therefore prolongs unemployment is a popular claim made by neo-liberals who seek to undermine systems of income support. There is no convincing research that establishes that proposition.

The conceptualisation comes from the (erroneous) view that mainstream economists have that mass unemployment is a supply-side phenomenon driven by the preferences of the workers for leisure when the real wage on offer is too low. This theoretical idea sees workers managing each hour of their day by making choices between leisure and income. Income can be gained only by working and work is conceived as bad and leisure good.

The price of leisure per hour is the foregone income or the real hourly wage. So as the real wage rises it become more expensive to enjoy leisure. A worker chooses leisure when their preference for it (the utility they gain from the extra hour) is greater than the real wage.

You will immediately see that the mainstream economics profession conceptualises unemployment as a choice of leisure. They argue there is always enough work around if the worker is prepared to take the real wage on offer (that is commensurate with their productivity).

As an aside, another major shortcoming of the model is that they conceive of productivity as being innate to an individual (either by nature or human capital investment) rather than being embedded in production and work processes which involve team-based outcomes. The industrial organisation literature, which the economists ignore, is full of evidence to support the latter construction of productivity.

Anyway in the context of this mainstream model, if you then introduce a “subsidy for leisure” which is how they conceive of the provision of unemployment benefits then you further distort the work-leisure choice in favour of leisure. So the dole becomes a subsidy for remaining jobless and the higher the payment the greater likelihood the individual will choose leisure. Further, the longer the payment is extended for the longer the individual will refrain from job search.

The survey literature finds overwhelmingly that unemployed workers will accept job offers made to them. The problem is that the lack of job offers not the income support regime in place (at the sort of levels that unemployment assistance is offered in various countries).

A major empirical flaw in the mainstream model is that they assume that quits rise when unemployment rises. This is because they consider movements from employment to unemployment are largely driven by workers realigning their choice of hours in favour of leisure. So the quit rate should rise if this behavioural explanation was accurate.

The fact is that quit rates are strongly counter-cyclical – they fall in a recession and rise in a boom. This simple fact completely obliterates the supply-side explanation of mass unemployment and students should be taught it on day one of their labour economics courses. Knowledge of that fact would avoid them having to wade through the nonsense that Barro and others have dished up to them over the years trying to convince them of the alternative view.

Second, at present in the US there is clearly a lack of jobs. So even if we accepted that the supply-side of the labour market has traction as the mainstream economics textbooks would like us to believe then that can only be the case if the the demand and supply relationships in the labour market intersect at the going real wage.

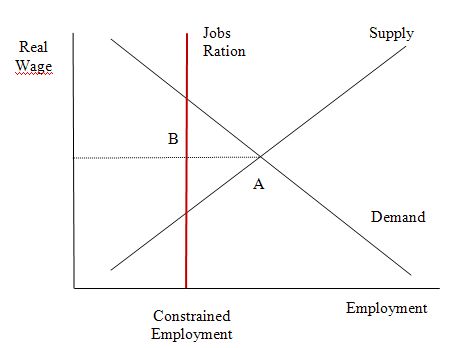

The following diagram explains this.

The mainstream model is the labour demand and supply model. Labour supply slopes upwards in terms of real wages because as the price of leisure rises workers are assumed to supply more hours of work. The demand for labour slopes downwards in their models because productivity declines per worker and so firms will only offer lower real wages to increase employment (so-called law of diminishing marginal productivity)

I don’t accept this model at all – and one day I will write a thorough critique of it. The fact is it fails to explain anything at the macroeconomic level and is also highly flawed at the microeconomic level. But for now let’s just assume it is the correct depiction of what goes on.

The real wage and employment level that the “market delivers” is at A in their model and so the supply relationship is playing a part to determine that nexus between supply and demand.

Now suppose there is a major failure in aggregate demand and a jobs ration (red vertical line) is imposed on the economy’s labour market. Then at that the going real wage, the “neoclassical” demand and supply curves have no bearing on the outcome which would be at point B.

So even if the supply relationship shifted (inwards a bit) as the unemployment benefits further reduced the hours they would be willing to supply at each real wage level, it would have no bearing on the outcome.

Third, the provision of unemployment benefits is likely to boost (or at least maintain) aggregate demand. The choice is between no income or some pitiful handout. So the extension of the income support will avoid a further collapse in spending by households. The loss of income arising from 10 per cent unemployment in the US (and up to 17 per cent if you count those who have given up looking) is enormous and highly deflationary.

The provision and extension of unemployment benefits will thus maintain spending and via multiplier effects could even provide stimulus to increase private employment.

That is why the US Democrats claimed this was a job plan. I think that is nonsense. It is a minor income support provision but better than the Republican alternative, which is based on spurious understandings of how the labour market functions.

Fourth, to further appreciate how mass unemployment arises, recall the parable of 100 dogs and 95 bones – now 90 bones in the US and elsewhere!

The main reason that the supply-side approach is flawed is because it fails to recognise that unemployment arises when there are not enough jobs created to match the preferences of the willing labour supply. The research evidence is clear – churning people through training programs divorced from the context of the paid-work environment is a waste of time and resources and demoralises the victims of the process – the unemployed.

Imagine a small community comprising 100 dogs. Each morning they set off into the field to dig for bones. If there enough bones for all buried in the field then all the dogs would succeed in their search no matter how fast or dexterous they were.

Now imagine that one day the 100 dogs set off for the field as usual but this time they find there are only 90 bones buried.

Some dogs who were always very sharp dig up two bones as usual and others dig up the usual one bone. But, as a matter of accounting, at least 5 dogs will return home bone-less.

Now imagine that the government decides that this is unsustainable and decides that it is the skills and motivation of the bone-less dogs that is the problem. They are not “boneable” enough.

So a range of dog psychologists and dog-trainers are called into to work on the attitudes and skills of the bone-less dogs. The dogs undergo assessment and are assigned case managers. They are told that unless they train they will miss out on their nightly bowl of food that the government provides to them while bone-less. They feel despondent.

Anyway, after running and digging skills are imparted to the bone-less dogs things start to change. Each day as the 100 dogs go in search of 90 bones, we start to observe different dogs coming back bone-less. The bone-less queue seems to become shuffled by the training programs.

However, on any particular day, there are still 100 dogs running into the field and only 90 bones are buried there!

You can find pictorial version of the parable here (for international readers this version was very geared to labour market policy under the previous federal regime in Australia and was written around 2001).

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Extending unemployment benefits … an omen

- Why are we so mean to the unemployed?

- Long-term unemployment – stats and myths

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 3:

The suggestion to create a European Monetary Fund is motivated by the desire to prevent sovereign defaults among member countries who are having trouble covering their net spending positions with market-sourced finance. The solvency risk is however sourced in the restrictions imposed on deficit and debt ratios by the Stability and Growth Pact which member states voluntarily agreed to.

The answer is False.

The proposal to create a European Monetary Fund is motivated by the desire to prevent sovereign defaults among member countries who are having trouble covering their net spending positions with market-sourced finance. That part is true although the reasoning advanced by the EMU bosses is spurious to say the least.

But the linking of solvency risk and the Stability and Growth Pact is false.

The Stability and Growth Pact which is summarised as imposing a rule on EMU member countries that their budget deficits cannot exceed 3 per cent of GDP rule and their public debt to GDP ratio cannot exceed 60 per cent. In the links provided below you will find extensive analysis of the nonsensical nature of these rules.

The SGP was designed to place nationally-determined fiscal policy in a straitjacket to avoid the problems that would arise if some runaway member states might follow a reckless spending policy, which in its turn would force the ECB to increase its interest rates. Germany, in particular, wanted fiscal constraints put on countries like Italy and Spain to prevent reckless government spending which could damage compliant countries through higher ECB interest rates.

In a 2006 book I published with Joan Muysken and Tom Van Veen – Growth and cohesion in the European Union: The Impact of Macroeconomic Policy – we showed that it is widely recognised that these figures were highly arbitrary and were without any solid theoretical foundation or internal consistency.

The current crisis is just the last straw in the myth that the SGP would provide a platform for stability and growth in the EMU. In my recent book (published just before the crisis) with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned – we provided evidence to support the thesis that the SGP failed on both counts – it had provided neither stability nor growth. The crisis has echoed that claim very loudly.

The rationale of controlling government debt and budget deficits were consistent with the rising neo-liberal orthodoxy that promoted inflation control as the macroeconomic policy priority and asserted the primacy of monetary policy (a narrow conception notwithstanding) over fiscal policy. Fiscal policy was forced by this inflation first ideology to become a passive actor on the macroeconomic stage.

But these rules, while ensuring that the EMU countries will have to live with high unemployment and depressed living standards (overall) for years to come, given the magnitude of the crisis and the austerity plans that have to be pursued to get the public ratios back in line with the SGP dictates, are not the reason that the EMU countries risk insolvency.

That risk arises from the fact that when they entered the EMU system, they ceded their currency sovereignty to the European Central Bank (ECB) which had several consequences. First, EMU member states now share a common monetary stance and cannot set interest rates independently. The former central banks – now called National Central Banks are completely embedded into the ECB-NCB system that defines the EMU.

Second, they no longer have separate exchange rates which means that trade imbalances have to be dealt with in monetary terms not in relative price changes.

Third, and most importantly, the member governments cannot create their own currency and as a consequence can run out of Euros! So imagine there was a bank run occuring in Australia, while the situation would signal mass frenzy, the Australian government has the infinite capacity to guarantee all deposits denominated in $AUD should it choose to do so. If the superannuation industry collapsed in Australia, the Australian government could just guarantee all retirement incomes denominated in $AUD should it choose to do so. The same goes for any sovereign government (including the US and the UK).

But an EMU member government could not do this and their banking or public pension systems could become insolvent.

Further, it could reach a situation where it did not have enough Euros available (via taxation revenue or borrowing) to repay its debt commitments (either retire existing debt on maturity or service interest payments). In that sense, the government itself would become insolvent.

A sovereign government such as Australia or the US could never find itself in that sort of situation – they are never in risk of insolvency.

So the source of the solvency risk problem is not the stupid fiscal rules that the EMU nations have placed on themselves but the fact they have ceded currency sovereignty.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Euro zone’s self-imposed meltdown

- A Greek tragedy …

- España se está muriendo

- Exiting the Euro?

- Doomed from the start

- Europe – bailout or exit?

- Not the EMF … anything but the EMF!

Question 4:

In the February Labour Force data for Australia released last Thursday, we learned that employment grew by only 400 in net terms during the month of February. Other highlights were that unemployment rose by 10,700 and that the labour force participation rate fell by 0.1 per cent indicating a rise in the proportion leaving the labour force. Taken together this data tells you that:

The answer is The labour force grew faster than employment but not as fast the working age population.

If you didn’t get this correct then it is likely you lack an understanding of the labour force framework which is used by all national statistical offices.

The labour force framework is the foundation for cross-country comparisons of labour market data. The framework is made operational through the International Labour Organization (ILO) and its International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS). These conferences and expert meetings develop the guidelines or norms for implementing the labour force framework and generating the national labour force data.

The rules contained within the labour force framework generally have the following features:

- an activity principle, which is used to classify the population into one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework;

- a set of priority rules, which ensure that each person is classified into only one of the three basic categories in the labour force framework; and

- a short reference period to reflect the labour supply situation at a specified moment in time.

The system of priority rules are applied such that labour force activities take precedence over non-labour force activities and working or having a job (employment) takes precedence over looking for work (unemployment). Also, as with most statistical measurements of activity, employment in the informal sectors, or black-market economy, is outside the scope of activity measures.

Paid activities take precedence over unpaid activities such that for example ‘persons who were keeping house’ as used in Australia, on an unpaid basis are classified as not in the labour force while those who receive pay for this activity are in the labour force as employed.

Similarly persons who undertake unpaid voluntary work are not in the labour force, even though their activities may be similar to those undertaken by the employed. The category of ‘permanently unable to work’ as used in Australia also means a classification as not in the labour force even though there is evidence to suggest that increasing ‘disability’ rates in some countries merely reflect an attempt to disguise the unemployment problem.

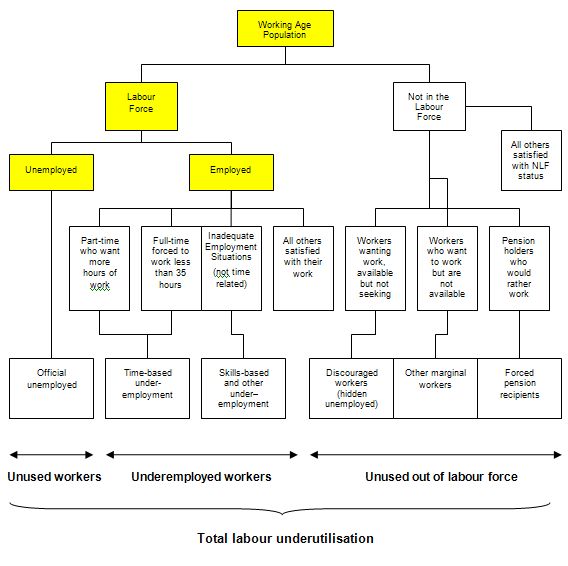

The following diagram shows the complete breakdown of the categories used by the statisticians in this context. The yellow boxes are relevant for this question.

So the Working Age Population (WAP) is usually defined as those persons aged between 15 and 65 years of age or increasing those persons above 15 years of age (recognising that official retirement ages are now being abandoned in many countries).

As you can see from the diagram the WAP is then split into two categories: (a) the Labour Force (LF) and; (b) Not in the Labour Force – and this divisision is based on activity tests (being in paid employed or actively seeking and being willing to work).

The Labour Force Participation Rate is the percentage of the WAP that are active. So in the case above the current Australian participation rate overall is 65.2 per cent. This means that 65.2 per cent of those persons above the age of 15 are actively engaged in the labour market (either employed or unemployed).

You can also see that the Labour Force is divided into employment and unemployment. Most nations use the standard demarcation rule that if you have worked for one or more hours a week during the survey week you are classified as being employed.

If you are not working but indicate you are actively seeking work and are willing to currently work then you are considered to be unemployed. If you are not working and indicate either you are not actively seeking work or are not willing to work currently then you are considered to be Not in the Labour Force.

So you get the category of hidden unemployed who are willing to work but have given up looking because there are no jobs available. The statistician counts them as being outside the labour force even though they would accept a job immediately if offered.

The question gave you information about employment, unemployment and the labour force participation rate and you had to deduce the rest based on your understanding.

In terms of the Diagram the following formulas link the yellow boxes:

Labour Force = Employment + Unemployment = Labour Force Participation Rate times the Working Age Population

It follows that the Working Age Population is derived as Labour Force divided by the Labour Force Participation Rate (appropriately scaled in percentage point units).

So if both Employment and Unemployment is growing then you can conclude that the Labour Force is growing by the sum of the extra Employment and Unemployment expressed as a percentage of the previous Labour Force.

The Labour Force can grow in one of four ways:

- Working Age Population growing with the labour force participation rate constant;

- Working Age Population growing and offsetting a falling labour force participation rate;

- Working Age Population constant and the labour force participation rate rising;

- Working Age Population falling but being offset by a rising labour force participation rate.

So in our case, if the Participation Rate is falling then the proportion of the Working Age Population that is entering the Labour Force is falling. So for the Labour Force to be growing the Working Age Population has to be growing faster than the Labour Force.

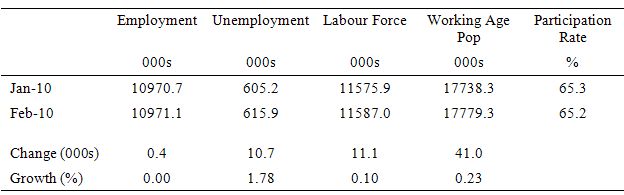

Now consider the following Table which shows the Australian labour force aggregates for January and February 2010 (the same that were used in the question).

You can see added information which demonstrates the point.

So the correct answer is as above.

Of the second option:

The working age population grew faster than employment and offset the decline in the labour force arising from the drop in the participation rate.

Clearly impossible if both employment and unemployment both rose.

And of the third option:

The labour force grew faster than employment but you cannot tell what happened to the working age population from the information provided.

Clearly you can tell what happened to the working age population by deduction.

Question 5:

If the household saving ratio rises and there is an external deficit then Modern Monetary Theory tells us that the government must increase net spending to fill the private spending gap or else national output and income will fall.

The answer is False.

This question tests one’s basic understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. The secret to getting the correct answer is to realise that the household saving ratio is not the overall sectoral balance for the private domestic sector.

In other words, if you just compared the household saving ratio with the external deficit and the budget balance you would be leaving an essential component of the private domestic balance out – private capital formation (investment).

To understand that, in macroeconomics we have a way of looking at the national accounts (the expenditure and income data) which allows us to highlight the various sectors – the government sector and the non-government sector (and the important sub-sectors within the non-government sector).

So we start by focusing on the final expenditure components of consumption (C), investment (I), government spending (G), and net exports (exports minus imports) (NX).

The basic aggregate demand equation in terms of the sources of spending is:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

In terms of the uses that national income (GDP) can be put too, we say:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume, save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

So if we equate these two ideas sources of GDP and uses of GDP, we get:

C + S + T = C + I + G + (X – M)

Which we then can simplify by cancelling out the C from both sides and re-arranging (shifting things around but still satisfying the rules of algebra) into what we call the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

There are three sectoral balances derived – the Budget Deficit (G – T), the Current Account balance (X – M) and the private domestic balance (S – I).

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but we just keep them in $ values here:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

You can then manipulate these balances to tell stories about what is going on in a country.

For example, when an external deficit (X – M < 0) and a public surplus (G - T < 0) coincide, there must be a private deficit. So if X = 10 and M = 20, X - M = -10 (a current account deficit). Also if G = 20 and T = 30, G - T = -10 (a budget surplus). So the right-hand side of the sectoral balances equation will equal (20 - 30) + (10 - 20) = -20. As a matter of accounting then (S - I) = -20 which means that the domestic private sector is spending more than they are earning because I > S by 20 (whatever $ units we like). So the fiscal drag from the public sector is coinciding with an influx of net savings from the external sector. While private spending can persist for a time under these conditions using the net savings of the external sector, the private sector becomes increasingly indebted in the process. It is an unsustainable growth path.

So if a nation usually has a current account deficit (X – M < 0) then if the private domestic sector is to net save (S - I) > 0, then the public budget deficit has to be large enough to offset the current account deficit. Say, (X – M) = -20 (as above). Then a balanced budget (G – T = 0) will force the domestic private sector to spend more than they are earning (S – I) = -20. But a government deficit of 25 (for example, G = 55 and T = 30) will give a right-hand solution of (55 – 30) + (10 – 20) = 15. The domestic private sector can net save.

So by only focusing on the household saving ratio in the question, I was only referring to one component of the private domestic balance. Clearly in the case of the question, if private investment is strong enough to offset the household desire to increase saving (and withdraw from consumption) then no spending gap arises.

In the present situation in most countries, households have reduced the growth in consumption (as they have tried to repair overindebted balance sheets) at the same time that private investment has fallen dramatically.

As a consequence a major spending gap emerged that could only be filled in the short- to medium-term by government deficits if output growth was to remain intact. The reality is that the budget deficits were not large enough and so income adjustments (negative) occurred and this brought the sectoral balances in line at lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Conclusion

That is enough for today!

Funny. Just yesterday I read Akerlof’s “The Missing Motivation in Macroeconomics”. And he delivers another very good reason why for instance mainstream labour economics is nuts. Once you introduce the concept that people have norms the whole framework breaks down. Natural or cultural norms how decision makers should behave change their utility function. For instance employees have a concept of how nominal wages should be. Thus the decision makers not only care about real wages like the neo-classsical agenda proclaims.

The concept of norms also relates to previous comment made Tom Hickey about economics and evolution. Cultural norms develop and change over time. Thus it can be argued that cultural evolution must be part of the economic theory. What I’m really wondering about is, this paper was written 2006 and as far as I can judge it’s effect on mainstream economics is the same as if it would not have been written. And I mean Akerlof is not an obscure heterodox economist? 😉 What’s wrong with the “science”?

Greetings,

I’ve just read http://www.washingtonsblog.com/2010/03/7-questions-about-public-banking.html

would someone who’s strong on understanding MMT comment on it please. Does it contradict on how the money is created according to MMT? That article suggest that new money is not only created by government but also by issuing new debt by banks. MMT to my understanding argues that only government can create financial assets in its own currency, but if the banks issue debt which in turn may or may not create new real/physical assets which means issuance of debt can also create financial assets provided it was not just used for speculation but used to produce tangible/useful stuff?

Also is MMT opposed to Steve Keen’s worldview, and if so in what ways?

Many thanks

hrvoje

hrvoje, I posted a lot on MMT over there in the past, but poor George just doesn’t seem to have taken the time to read the references. I posted again today, telling him he was at least making some progress but still doesn’t understand monetary/fiscal operations in a modern economy and he needs to read Randy Wray’s book. I’ve kind of given up hope on him. He doesn’t seem to want to get it. Because he doesn’t get it, he jumbles all kind of stuff together, most of which is just wrong. I don’t know why Yves has him guest posting at her place so much. He’s a distraction.

Last MIle update: Warren Mosler is at the top of the blog list at The Hufington Post/Business today. His post is on the EU crisis and not directly on MMT, but it’s giving Warren some good exposure.

Also is MMT opposed to Steve Keen’s worldview, and if so in what ways?

See these links and comments at Steve’s place. Scott Fullwiler’s comment at the first link says it all. There is no disconnect between Chartalism and Circuitism when they are properly understood, that is, operationally. Some MMT’ers have criticized of Steve’s use of accounting, though, since he tends to depart from accepted terminology and practice in ways that fit his model, creating some confusion.

Chartalism-vs-MMT

Chartalist & Circuitist analyses of money

If you read some of the comments in the second link, you will find that a lot of the commenters don’t have a clue, so there a whole mythology has grown up around this “feud.” Much ado about nothing.

Dear Tom

In your summation of the Steve Keen v MMT you concluded “Much ado about nothing”.

I don’t agree. The fundamental point is that you cannot understand the circuits without a prior understanding of the government/non-government relationship. To talk about “monetary systems” without an explicit analysis of government is fraught.

Then we get to the accounting errors that riddle the analysis that purports to be a pure credit economy.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

I agree, of course, with your point. There are significant qualitative differences between our “taxes drive money” view and the fact that they begin analysis with credit money.

I don’t know that you were referring at all to my quote Tom linked to , but my point was that in terms of the accounting and basic quantitative model of the real world monetary system, there’s little difference between us and the main horizontalists like Lavoie, Rochon, Seccareccia, Moore, etc. We have completely incorporated the horizontalist model, and the aforementioned horizontalists are generally in agreement with our basic model. For instance, I don’t think any of them would disagree with your previous posts on the simple business card economy. Indeed, Lavoie’s book with Godley uses the exact same quantitative/accounting approach you are using there. Further, I am in regular contact with Marc, Mario, and LP, and we are in general agreement on the real-world mechanics, operations, and accounting between banks, Treasury, central bank, and non-bank private sector. That was my point in the link Tom is providing–I wanted to emphasize that it is only those commenting on Steve’s site that are dreaming up significant differences between the horizontalist model and the MMT model regarding those issues.

The discussion there has rarely if ever mentioned the more significant, fundamental differences you are pointing out.

Best,

Scott

Thank you Tom and Bill,

on that blog pointed by Tom (http://www.talkfinance.net/f36/chartalist-and-circuitist-analyses-money-497/) it says

“Monetary circuit theory is a heterodox theory of monetary economics, particularly money creation, often associated with the post-Keynesian school. It holds that money is created endogenously by the banking sector, rather than exogenously by central bank lending; it is a theory of endogenous money. It is also called circuitism and the circulation approach.”

and for MMT “Modern chartalism theory states that under a fiat money system, money is created by government deficit spending. Because money is not tied to or backed by a commodity, money can only be created when the government spends money”.

how about a simple scenario

a) MMT government give a private enterprise 10mill to build a bridge, bridge gets built, we have a useful asset. Government is in deficit 10mill. Money never has to be paid back. Deficit gets recorded in excel spread sheet.

b) Circuit/keen version. Bank creates/issues 10mill of debt to a private enterprise, bridge gets build, we have a useful asset. Bank is in deficit until 10 mil gets payed back. Which it will eventually via tolls etc. In this case money has to be paid back.

So what is the difference between scenarios? And what is the point of issuing private debt, why not always get government to finance stuff?

Thanks for clearing up that point, Bill and Scott. My apparently mistaken impression arose from Scott’s quote was that there is no disconnect among the Chartalists and Circuitists, and I concluded from some of Steve’s recent statements that he is on board with the vertical-horizontal distinction, too. Many in his tribe haven’t caught up with that it seems, and continue to claim Chartalists assert that all money creation is from the government side alone (“exogenous,” outside) and deny private money creation in the banking system (“endogenous,” inside). As far as I am aware, that is the major kerfuffle. I’m not up to date on what’s happening over there, however, but I had heard that Steve corrected them on that. I know there are disagreements with Steve on macro, too, regarding his insistence on dynamic models. But the question was specifically about Steven and MMT, which has been specifically about debt in money creation, the way I’ve understood it.

hrvoje, my understanding is that the circuit theorists are referring to private banks creating “broader money”, usually defined to include private demand deposits (which banks can create through lending) as well as currency. This occurs through horizontal transactions within the non-government sector.

When MMT says that only government can create money, it is referring to high-powered money (reserves, coins, notes, Treasury cheques). The amount of high-powered money can only change through vertical transactions between the government and non-government sector.

The two points are not contradictory. Private banks cannot create or destroy high-powered money, but they can and do create broader money (private demand deposits) through their lending behaviour.

Another way of looking at this is that horizontal transactions can never alter the net financial assets of the non-government sector. This is because a horizontal transaction always creates an asset and a matching liability. In contrast, the government has the capacity to create or destroy high-powered money by running budget deficits or surpluses, and this results in a change in the net financial assets of the non-government sector.

The reason private banks extend loans rather than leaving the government to finance everything is that the banks want to make a private return on their lending. It is the profit motive. Personally, though this is not based on MMT, I think we should get rid of profit, private banks, interest, etc., altogether, but not enough people in the world agree with me. 🙂