I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

I guess they didn’t want to win the war

Today in NSW it reached 41 degrees Celsius again. The bushfire season has started early and of-course we all conclude it is related to climate change. But I was thinking about other things – to wit – the difficulty new ideas that have relatively complex underpinnings face in gaining traction in the public debate which is saturated by single line mantras that the media loves to repeat over and over again. This thinking was, in part, motivated by two opinion polls I examined from the US. The second one indicated that a growing (and already dominant) proportion of US citizens want the US government to run balanced budgets. How I thought would they think that would work?

A recent Gallup opinion poll found that only 49 per cent of Americans now approve of Obama’s performance as president. Almost all of the decline in his rating occurred between July and August (he was around 70 per cent in February and 60 percent at the end of June). Gallup report that:

Of the post-World War II presidents, Obama now is the fourth fastest to drop below the majority approval level, doing so in his 10th month on the job. Gerald Ford dropped below 50% approval during his third month in office, and Bill Clinton did so in his fourth month. Ronald Reagan, like Obama, also dropped below 50% in his 10th month in office, though Reagan’s drop occurred a few days sooner in that month (Nov. 13-16, 1981) than did Obama’s (Nov. 17-19, 2009).

In a related national CNN telephone poll of 1,014 adult Americans (including 928 registered voters) was conducted on November 13-15, 2009 and sought to determine which political party is to blame for the recession has found that sentiment is “shifting”:

… 38 percent of the public blames Republicans for the country’s current economic problems. That’s down 15 points from May, when 53 percent blamed the GOP. According to the poll 27 percent now blame the Democrats for the recession, up 6 points from May. Twenty-seven percent now say both parties are responsible for the economic mess.

So there is now growing number of US citizens firmly of the view that the current Administration is to blame and a majority that consider it carries at least some blame. More than 53 per cent of Americans now think that Obama has made things worse (28 per cent) or had no effect (35 per cent).

I largely agree that Obama has probably made things worse. In the time that Obama has been in power he could have used his fiscal capacity such that the US economy could have been in recovery months ago. Instead he has failed to arrest the rise in unemployment and has also failed to restructure and re-regulate the financial system (for example, separating banking from speculative investment activity – I will write a blog about this soon).

In other words, the US Government’s policy position under Obama has left the US economy vulnerable to further collapse in the future.

The survey report suggests that “the growing federal budget deficit: Two-thirds say that the government should balance the budget even in a time of war and recession” is behind the growing negative view about Obama.

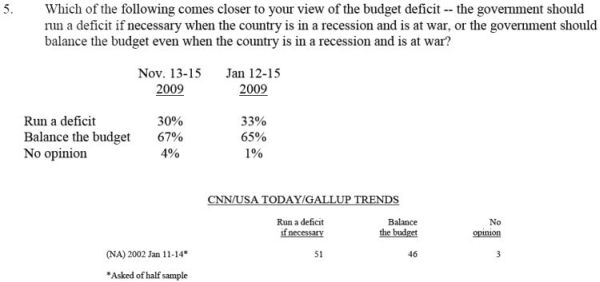

The following graphic shows the responses to Question 5 from the CNN Opinion Research Poll:

So as the US economy continues to nose-dive in mid-November 2009, only 30 per cent (down from 33 per cent in mid-January) of US citizens polled thought the government should run a deficit. A staggering 67 per cent (up from 65 per cent) thought the US government should balance the budget. In January 2002 51 per cent thought a deficit was okay and 46 per cent wanted a balanced budget.

I take this result to mean that at least 67 per cent of Americans are victims of an education system that has failed them. The other 30 per cent may also be but at least on this question that cannot be concluded.

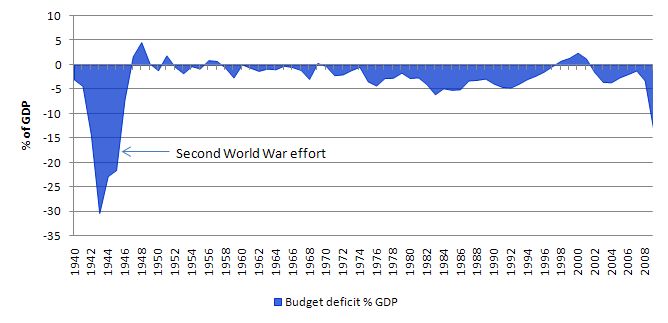

The next graph shows US Government budget position as a percentage of GDP (deficits are below the zero line) from 1940 to 2009, using the excellent data available from US Bureau of Economic Analysis. You can see what size deficit the war effort in the early 1940s involved. Major catastrophes and recessions by definition require large deficits.

It also suggests – if the opinions were actually informed rather than pavlovian reactions to the anti-government media onslaught – that the American people didn’t want to win the Second World War and would have been happy with a permanent state of very high unemployment and poverty.

Moreover, a perpetual state of a balanced national budget is almost impossible to conceive in an economy that trades and saves.

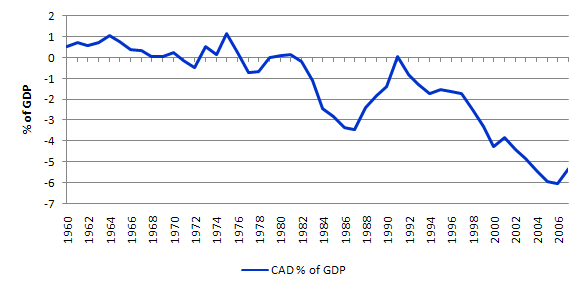

As part of our understanding the following graph shows the US current account deficit as a percentage of GDP from 1960 to 2007. Remember a CAD is a sign that foreigners wish to accumulate financial assets denominated in that particular nation’s currency and are prepared to deny their own citizens access in net terms to real goods and services (which generate material welfare) to realise that desire.

Do these desires change quickly or substantially? In the literature there has been work analysing so-called current account reversals. A serious reversal is considered to be an adjustment of more than 4 per cent in a one year period that sums to a 5 per cent of GDP reduction over 3 years.

A serious current account reversal would be a sign that foreign desires to accumulate a particular nation’s currency had rapidly waned. The data shows categorically that the incidence of reversals for industrial countries is very small (less than 1.5 per cent). There is no historical evidence to support an argument that large economies like the US under significant current account adjustments.

So for all those doom merchants out there who invoke all sorts of catastrophe theories about the impending disaster because the CAD is now in solid deficit (and increasing as a percentage of GDP) please go and study the data and the history of world economies.

However, this graph helps us understand one other point that seems to be lost in the debate. If you put this information together with the fact that prior to the mid-1990s the household saving ratio in the US averaged between 7-10 per cent. It plunged after that as the debt binge began and is now firmly back in positive territory – around 5 per cent and rising – it could be 6-8 per cent by now.

So there is an expenditure leakage coming from the external sector (around 6 per cent of GDP) and also from domestic saving (say around 5 per cent of GDP). This indicates that the budget deficit has to be at least around 11-13 per cent of GDP is required to stop downward income adjustments from occurring. This is just “back of the envelope” reasoning. The fact is that the current deficit is not large once you consider the other national income aggregates (the expenditure leakages).

That size deficit is adding back demand that is being lost via the CAD and domestic saving.

If you try to cut the budget deficit at present in an discretionary manner, then you will bring about a drop in the CAD and domestic savings but only because GDP would fall as a consequence of the loss of aggregate demand.

What the deficit terrorists have to tell us is – (a) if the US is going to continue running a CAD (and that will not change any time soon). and (b) if they want the domestic sector to repair their balance sheets which were damaged during the credit binge – then (c) what magic formula have they invented that is in violation of the other basic national accounting fact – the first two facts require a budget deficit – by hook or by crook?

The fact is that at the level of reality – understanding the way the national aggregates work – the deficit terrorists have no answers.

No analysis of how interest rates are set is provided. No understanding of banking operations is provided. No understanding of basic national accounting.

Yet the uneducated above who would have allowed the US to be destroyed during the Second World War believe him.

To understand all of this we have to fully understand how the budget balance is arrived at. This is why modern monetary theory (MMT) is a powerful framework. None of the mainstream approaches (Austrian, neo-classical, new classical, new Keynesian) rival it in this respect.

Here is a way of thinking about these issues.

In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned we write in Chapter 8 that the introduction of “State money introduces the possibility of unemployment”.

Once we realise that government spending is not revenue-constrained then we have to analyse the functions of taxation in a different light … taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

The orthodox conception is that taxation provides revenue to the government which it requires in order to spend. In fact, the reverse is the truth. Government spending provides revenue to the non-government sector which then allows them to extinguish their taxation liabilities. So the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending.

It follows that the imposition of the taxation liability creates a demand for the government currency in the non-government sector which allows the government to pursue its economic and social policy program.

This insight allows us to see another dimension of taxation which is lost in orthodox analysis. Given that the non-government sector requires fiat currency to pay its taxation liabilities, in the first instance, the imposition of taxes (without a concomitant injection of spending) by design creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector.

The unemployed or idle non-government resources can then be utilised through demand injections via government spending which amounts to a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector. In turn, this transfer facilitates the government’s socio-economics program.

While real resources are transferred from the non-government sector in the form of goods and services that are purchased by government, the motivation to supply these resources is sourced back to the need to acquire fiat currency to extinguish the tax liabilities. Further, while real resources are transferred, the taxation provides no additional financial capacity to the government of issue.

Conceptualising the relationship between the government and non-government sectors in this way makes it clear that it is government spending that provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

So it is now possible to see why mass unemployment arises. It is the introduction of State Money (which we define as government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economics that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment.

As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal total income (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not each period).

Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages). Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account through the offer of labour but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal.

As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment. In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

So the purpose of State Money is to facilitate the movement of real goods and services from the non-government (largely private) sector to the government (public) domain. Government achieves this transfer by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue.

To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed. The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets).

From the previous paragraph it is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and the non-government sector’s desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In our conception, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending (saving) decisions in force at any particular time.

For a time, what may appear to be inadequate levels of net government spending can continue without rising unemployment. In these situations, as is evidenced in countries like the US and Australia over the last several years, GDP growth can be driven by an expansion in private debt.

The problem with this strategy is that when the debt service levels reach some threshold percentage of income, the private sector will “run out of borrowing capacity” as incomes limit debt service.

This tends to restructure their balance sheets to make them less precarious and as a consequence the aggregate demand from debt expansion slows and the economy falters. In this case, any fiscal drag (inadequate levels of net spending) begins to manifest as unemployment.

The point is that for a given tax structure, if people want to work but do not want to continue consuming (and going further into debt) at the previous rate, then the Government can increase spending and purchase goods and services and full employment is maintained. The alternative is unemployment and a recessed economy.

Conclusion

So next time Peter Schiff or others like him start mounting their attacks on government deficits think about whether they are really allowing you to understand these essential relationships that apply in a modern monetary economy.

In all the reading of their stuff I have done over the years – nothing much goes beyond the single phrase slogan – like deficits crowd out private investment – or taxes stifle incentive. No correspondence is provided between these statements and the way the monetary system operates nor the empirical evidence that is available.

Surely the CAD has to fall? The reason for the large CAD deficit over the last decade in the US was caused by a fall in the consumer (as opposed to the corporate) savings rate. During that period, the government should have run a surplus to off-set the fall in the private sector savings rate. Instead it ran what is now highlighted to be a structural deficit (same is even more true in the UK). Therefore over the government deficit, only around half of it is cyclical (and therefore “defendable” as a pro-cyclical stimulus). The rest is structural and at some point should be eliminated (although I would agree not right now).

The US (and UK, NZ and a lesser extent Australian) consumer needs to save more, rebuild its balance sheet. That will dramatically reduce the CAD is those countries. Currency depreciation would be helpful in achieving this.

Great work, Bill. It is truly shocking how the majority here in the US think that not only reducing the deficit but also eliminating the national debt will result in eternal prosperity for all, especially when an overwhelming number of people are dissatisfied with the government on the economy and unemployment, and want the government to fund programs to increase employment (71.6%) and funds states that are in financial difficulty (62.7%). (Here are some poll results – http://www.openleft.com/diary/15990/versailles-vs-america-part-305693). Bit of a disconnect here. The Obama Administration and Democratic Congress are faced with a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t dilemma in this bipolar atmosphere in which populism is becoming an increasingly significant factor that politicians have to reckon with.

While I completely agree that ultimately it is ignorance of MMT that is responsible, there are also other forces at work to sow disinformation, on on hand, and perpetuate the status quo through intellectual capture, on the other. The fact is that not much can change politically in the US without getting the money out of politics and closing the revolving door. Until that happens, the US will continue to be ruled by an oligarchy that shapes policy. There is a popular revolt brewing, so we’ll see where that goes. Right now, people are lashing out in anger, but they haven’t got a clue about workable solutions. Hence, they are just compounding the problem.

Moreover, the economics profession is dominated by orthodoxy that has a lock on the academic and professional universe of discourse and promulgates policy through the revolving door. So the field is tilted away from MMT’s getting a foot in the door. If it weren’t for the net, chances would be slim that MMT would ever get beyond a few professional articles and books that the dominant elite would never think of picking up, let along reading. But this was the state of affairs in academic psychology when B. F. Skinner made behaviorism aka rat psychology dominant, marginalizing other ideas – until Abraham Maslow came along and revolutionized the field with humanistic and then transpersonal psychology. So there’s hope. Keep up the great work.

Dear Nic

Thanks for your comment and welcome to billy blog.

The CAD probably has to fall – I agree given as you say it was driven by unsustainable private debt growth. But I would be careful in making what appears to be an implicit assumption that the private debt was unrelated to previous government fiscal positions. The Clinton surpluses have a lot to be accountable for in the sense they squeezed the private domestic sector liquidity and gave them no choice but to increase borrowing or recess.

I also agree that the US household (and in the other nations) have to save more – and that will cut the CAD but the point is that you want that to happen without a major contraction in output and employment. So that process has to be supported by budget deficits, which do not have to simultaneously drive the external account.

best wishes

bill

Just trying to get a feel for the ‘back of the envelope’ numbers Bill and the overall position of the US: if the expenditure leakages and the current budget deficit are about equal; and most of the deficit spending has gone to the financial sector with apparently minimal effect on the real sector – how much as a %GDP is the real economy under-resourced? Are there more setbacks to emerge from the financial sector? Nothing seems politically feasible given the current ideology?

Regarding ‘a soverign government is not revenue constrained’ insight thought you might like this (out-of-context)quote from Kabir: “The fish is thirsty in the water – every time I hear that it makes me laugh”.

Cheers …..

jrbarch

Hi Bill,

Here is a graph that illustrates trends in debt, from flow of funds data. I think it encapsulates both our concerns well.

Notice that in the period 1952-1982 — the shrinking of government debt is made possibly only by an increase in private sector debt elsewhere (household or business debt). Notice how flat and constant total debt is — an amazing correlation. Why would total debt be so flat? You do not need debt to grow if the current account is constant and if median incomes are growing at the same rate as all other incomes. In fact, it cannot grow.

But also look at the growth of aggregate debt following the tax cuts and deregulation of the early 1980s. How to decide if government was supplying enough debt in this case? Look at “leverage”, or the ratio of private non-financial debt to government debt (net of foreign debt). As government debt is an asset, this is a fair definition.

You cannot blame the government for spending too little between 1983-1998, as government was supplying more than enough assets to the private sector. You can maybe argue that the debt was not distributed appropriately, e.g. spending too much in one year and too little in the next, but over the period as a whole, the government supplied enough assets to the private sector. The response of the private sector was to push median wages down even more — the demand for financial assets is infinite.

The gross amount of debt required is the sum of the discrepancy between top incomes and their propensity to consume together with real investment needs and the current account. A good short-hand is to look at the difference between GDP growth and median income growth.

Here are two back of the envelope calculations: From 1952-1982, both GDP and real median incomes were rising at the same rate, so you would expect Debt/GDP to be constant, which was the case — amazingly constant.

From 1982-2009, GDP has been rising at a real rate of slightly less than 3% faster than median incomes, so you would expect Debt/GDP to about double in that period — which has also been the case. In that case, unless government debt doubles, total leverage will go up, which it has.

As a result, you can blame the government for spending too little, or you can blame the private sector for accumulating too much. It just depends on your point of view. My point of view is that if you need an incomes policy or other tool to put a ceiling on the financial accumulation, before agreeing to put a ceiling on leverage.