I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Fake surveys and Groupthink in the economics profession

In recent weeks, it has become apparent that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has evolved into a new ‘status’. Our work is everywhere now and has penetrated the political process (particularly in the US). At the same time, the mainstream macroeconomists continue to make fools of themselves by backtracking on some of their predictions that were made early in the GFC (about inflation, solvency, interest rates, bond yields, etc) and attacking MMT economists who actually provided correct analysis of what would happen in terms of these aggregates. The new ‘status’ means that MMT is now a visible challenger and the old guard hate that. All manner of critiques are emerging and the heartland of the mainstream approach at the University of Chicago recently trumped up a survey as evidence that MMT is crazy stupid. Some of the more odious mainstreamers then chose to disseminate the survey results as a sort of glorious statement of victory over MMT. The only problem was that the survey had nothing to do with the body of work we refer to as MMT and so was a dishonest exercise. The other problem was that the survey respondents were too insular (I didn’t say stupid) to realise they were being duped by Chicago Booth. None commented that the two questions that were under the heading ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ bore no resemblance to any core MMT statements or learnings. All this told me was that Groupthink is crippling the economics profession.

Groupthink

I have written about this topic previously.

I construct my thesis in my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – on this concept.

Irving Janis – introduced his theory of Groupthink – in his 1972 book – Victims of groupthink; a psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes.

He identified communities of scholars working within a dominant culture, which provides its members which a sense of belonging and joint purpose but also renders them oblivious and hostile to new and superior ways of thinking.

The group dynamics becomes a sort of ‘mob-rule’ that maintains discipline within paradigms. Conformity is required if one wishes to remain within the group and benefit from it personally.

It has also been defined as “a pattern of thought characterized by self-deception, forced manufacture of consent, and conformity to group values and ethics” (Merriam-Webster on-line dictionary).

Janis listed 8 characteristics or traits that defined the pattern of group behaviour he called Groupthink:

1. Denial of vulnerability – group members may not be willing to acknowledge their own fallibility or vulnerability.

2. Rationalization of decisions to minimize objections.

3. Belief in the absolute goodness of the group.

4. Intense dislike of outsiders – stereotyped and misleading portrayals of outside members and those who have left the group.

5. Group protectors – the spontaneous emergence of individual members who protect the group from conflicting information and perceived threats.

6. Strong peer pressure on all group members, particularly those who question group decisions.

7. Censorship of any disagreements within the group.

8. Belief that the group is unanimous and cohesive, even when some members object to the behavior of the group.

If you understand the way most graduate programs in economics operate or have worked in the academy for long enough, then you should easily be able to identify these 8 characteristics.

Individuals might have wondered about certain things when what was being taught was contrary to evidence that was freely available.

But most soon learn that to remain part of the group (and not be seen as an outsider) the doubts have to be suppressed. Over time, the aspiration to be successful within the group overwhelm any individual doubts.

The hardliners in the group run the morality play – good versus evil, freedom against oppression, capitalism against socialism.

It becomes simple – ideology is for socialists, mainstream economics just deals with objective realities.

And the rest of it.

I was an outsider and felt all the pressures but resisted them. It helped to hang out with historians, philosphers, musicians and the like.

The economics profession is rife with Groupthink.

And you don’t have to take my word for it.

In 2011, the IMF’s Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) released its audit – IMF Performance in the Run-Up to the Financial and Economic Crisis: IMF Surveillance in 2004-07 – which present a scathing assessment of the institution’s performance in the lead up to the GFC.

The IEO identified neo-liberal ideological biases at the IMF and determined that the IMF failed to give adequate warning of the impending GFC because it was “hindered by a high degree of groupthink” (p.17), which, among other things suppressed “contrarian views” where an “insular culture also played a big role’ (p.17).

The report said:

Analytical weaknesses were at the core of some of the IMF’s most evident shortcomings in surveillance … [as a result of] … the tendency among homogeneous, cohesive groups to consider issues only within a certain paradigm and not challenge its basic premises.

The prevailing view among IMF staff – a cohesive group of macroeconomists – was that market discipline and self-regulation would be sufficient to stave off serious problems in financial institutions.

They also believed that crises were unlikely to happen in advanced economies, where ‘sophisticated’ financial markets could thrive safely with minimal regulation of a large and growing portion of the financial system.

The External Evaluation Report says that “IMF economists tended to hold in highest regard” (p.18) economic models of the world proven to be inadequate (so-called Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium models).

Willem Buiter wrote in the Financial Times (March 9, 2009) that these economic models were useless “self-referential, inward-looking distractions at best”, which “excludes everything relevant to the pursuit of financial stability”.

In his New York Times article (November 2, 2008) – Challenging the Crowd in Whispers, Not Shouts – economist Robert Schiller says Groupthink tells us why “panels of experts could make colossal mistakes”, implicates the US Federal Reserve (and central banks in general) in this self-censoring behaviour where “mavericks” are put under intense pressure if they question the “group consensus”.

In his 2009 article (May 13, 2009) – Priceless: How the Federal Reserve Bought the Economics Profession – Ryan Grim concluded after a detailed investigation that:

The Federal Reserve, through its extensive network of consultants, visiting scholars, alumni and staff economists, so thoroughly dominates the field of economics that real criticism of the central bank has become a career liability for members of the profession.

Not only does the US Federal Reserve fund a huge amount of non-staff economic consultancies but also “keeps many of the influential editors of prominent academic journals on its payroll”.

By controlling what gets published in the key journals, the bank also influences the career trajectory of economists, and thus suppresses independent research that might be critical of the way the central bank operates.

The US Federal Reserve has an “intolerance for dissent”, something that well-known economist Alan Blinder found out quickly, when he joined the the bank as a vice chairman.

He lasted around 18 months after “a lot of senior staff … were pissed off … [because he was] … not playing by the customs that they were accustomed to”.

His sin?

He asked too many questions and challenged to many assumptions.

Even a moderate critic of the bank, Paul Krugman – reported – that he was “blackballed from the Fed summer conference at Jackson Hole … ever since I criticized” Governor Alan Greenspan.

How Groupthink works – in practice

In my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – I introduced the struggle that American biologist Joseph Altman had in gaining acceptance for his discovery of adult neurogenesis in the 1960s.

In his October 2000 article in – Neurogenesis in the adult brain: death of a dogma – published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Charles Gross wrote that:

Until very recently, a central dogma of neuroscience has been that new neurons are not added to the adult mammalian brain. For more than 100 years it has been assumed that neurogenesis, or the production of new neurons, occurs only during development and stops before puberty

He noted that “In the first half of the twentieth century, there were occasional reports of postnatal neurogenesis in mammals” which these insights “tended to be ignored by textbooks and were rarely cited”.

Why?:

Presumably this was because of the weight of authority opposed to the idea and the inadequacy of the available methods both for detecting cell division and for distinguishing glia from small neurons.

However:

Starting in the early 1960s, Joseph Altman began publishing a series of papers … in which he reported … evidence for new neurons in various structures in the young and adult rat … Although published in the most prestigious journals of the time … these findings were ignored or dismissed as unimportant for over two decades …

The neglect of Altman’s demonstration of adult neurogenesis is a classic case of a discovery made ‘before its time’.

What explains the neglect of Altman’s work?

Charles Gross lists a number of reasons, some technical in nature, but said:

… an important reason for the neglect of Altman’s work may have been that he was a self-taught postdoctoral fellow working on his own in a Psychology Department (at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)) and that his work was attempting to overturn a central and, by then, universally held tenet of neuroscience. Altman was not granted tenure at MIT and moved to Purdue University where he eventually turned to more conventional developmental questions … possibly because of the lack of recognition of his work on adult neurogenesis. As late as 1970, an authoritative textbook of developmental neuroscience … stated that “… there is no convincing evidence of neuron production in the brains of adult mammals.

[Reference: Gross, C. (2000) ‘Neurogenesis in the adult brain: death of a dogma’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 1, 67-73.]

He cites the work of another biologist in the field, Michael Kaplan (and co-authors) who in “a series of electron microscopy studies some “Fifteen years after Altman’s first report” gave “direct support for his claim of adult neurogenesis”.

Again, “In spite of his evidence for adult neurogenesis, Kaplan’s work had little effect at the time … [publications] … by an unknown figure was not sufficient to make any marked dent in the dogma.”

This is Groupthink.

If you are interested in this topic then I can recommend that you read I. Bernard Cohen’s 1985 711-page book – Revolution in Science (Harvard University Press).

He documents many examples in evolution of science where a dominant orthodoxy resists the discovery of new evidence or new ways of thinking that challenge the careers and positions of the dominant scientists in the field.

The problem for an orthodoxy that is degenerating (as in Imre Lakatos’ conceptualisation) – that is, losing empirical content (or being able to provide adequate explanations for real world phenomena) is that eventually the facts outpace the attempt to subvert or deny them.

In the case of neurogenesis, in the period after Altman published his findings in the early 1960s, many researchers stumbled on similar insights.

There were new techniques introduced (ways of doing research and articulating concepts) and links made to other disciplines (such as psychology), which brought things to a head.

By the 1990s, the denial of the orthodoxy was becoming unsustainable in the lift of the mounting evidence to the contrary.

Prominent in the research at this stage was Elizabeth Gould and her team and Charles Gross wrote that:

So more than 100 years after the formulation of the neuron doctrine, it was finally clear that its corollary ‘new neurons are not added to the adult mammalian brain’ is false: even for adults, even for primates and, apparently, even for the cerebral cortex.

As he puts it “The dogma crumbles”.

His assessment at that point was that:

The tenacious persistence of this dogma in the face of empirical contradiction and its relatively recent demise illustrates, among other things, the strength of tradition and the difficulty that unknown and junior scientists have in challenging such traditions. It also suggests the necessity for new ideas to arise in a supportive matrix if they are to survive, and under scores the importance of new techniques. The general acceptance of adult neurogenesis today … is suggestive of a paradigm shift.

Later, in his 2008 article – Three before their time: neuroscientists whose ideas were ignored by their contemporaries – Charles Gross reflected on the “neuroscientists whose ideas were ignored by their contemporaries but were accepted as major insights decades or even centuries later”.

[Reference: Gross, C.C. (2008) ‘Three before their time: neuroscientists whose ideas were ignored by their contemporaries’, Experimental Brain Research, 192(3), January, 321-34.]

In the case of Joseph Altman, Charles Gross wrote that:

1. “Altman was not granted tenure at MIT and moved to Purdue University where he eventually turned to more conventional developmental questions”.

2. “Unable to get grants he supported his work by producing magnificent brain atlases”.

3. “As late as 1970, an authoritative textbook of developmental neuroscience” denied Altman’s research findings (although did not refer to them, just maintaining the orthodoxy.

4. In response to Kaplan’s supportive findings, the orthodoxy claimed, among other things, that “adult neurogenesis in rats” is impossible

because “rats never stop growing and so never become adults”.

5. The later “the evidence for avian neurogenesis was viewed as an exotic specialization related to the necessity for Xying creatures to have light cerebrums and to their seasonal cycles of singing” – think about the way mainstream economists treat their failure to understand Japan.

6. “Altman, although in a leading university (MIT), was at the time of his early adult neurogenesis papers a self-taught post-doc- toral fellow in a psychology department and had not been trained in a distinguished, or indeed, any developmental laboratory or one using autoradiographic techniques.”

7. “the dogma of “no new neurons” was universally held and vigorously defended by the most powerful and leading primate developmental anatomist of his time.”

[Reference: Gross, C.C. (2008) ‘Three before their time: neuroscientists whose ideas were ignored by their contemporaries’, Experimental Brain Research, 192(3), January, 321-34.]

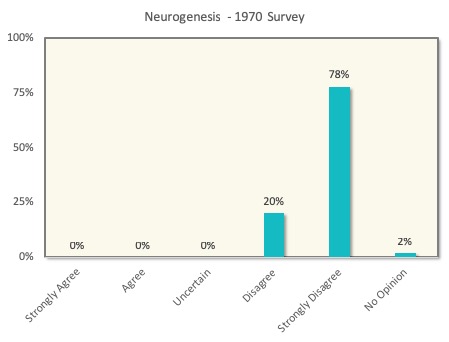

So we conduct a survey in say 1970

Now, imagine that some survey firm conducted a survey of neurogenesis scientists in the 1960s or 1970s and asked them something like: Do you think that adults are capable of developing new neurons?

We would get a graph like this one (probably).

The extant profession would have been firmly behind the “leading primate developmental anatomist” at the time – via the implicit pressures operating in the laboratories doing this type of work.

The strength of the opinion would have been heavily weighted in favour of the orthodoxy.

Dissent would have been seen as a sign that one wasn’t serious about pursuing a career in this field and junior scientists seeking tenure would be under pressure to conform, even if they had read the work of Altman and later Kaplan and others.

History tells us that the science underpinning these opinions was plain wrong!

Now imagine that the survey firm then rejigged the survey question to distort the message that Altman’s research was disclosing yet still attributed this rejigged question to be representative of Altman’s research.

The results would have been two-fold:

1. The dominant orthodoxy would have still voted in the same way.

2. They would have concluded that Altman was crazy, was offering up ‘garbage’ and was even ‘dangerous’ for giving brain injured patients hope.

Fast track to 2019.

Then trump up a survey and all the lemmings jump over the cliff

The mainstream macroeconomcis group protectors have been out in force in recent weeks denying, rationalising, expressing disdain for Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) academics, and seeking to express a sense of unanimity across their discipline.

So they came up with a survey.

The University of Chicago Booth School of Business is part of the University of Chicago.

They are the bastion of mainstream economics – both macro and micro.

They run a so-called “Economic Experts Panel” which “explores the extent to which economists agree or disagree on major public policy issues”.

The Panel is comprised of the senior ‘priests’ in the profession.

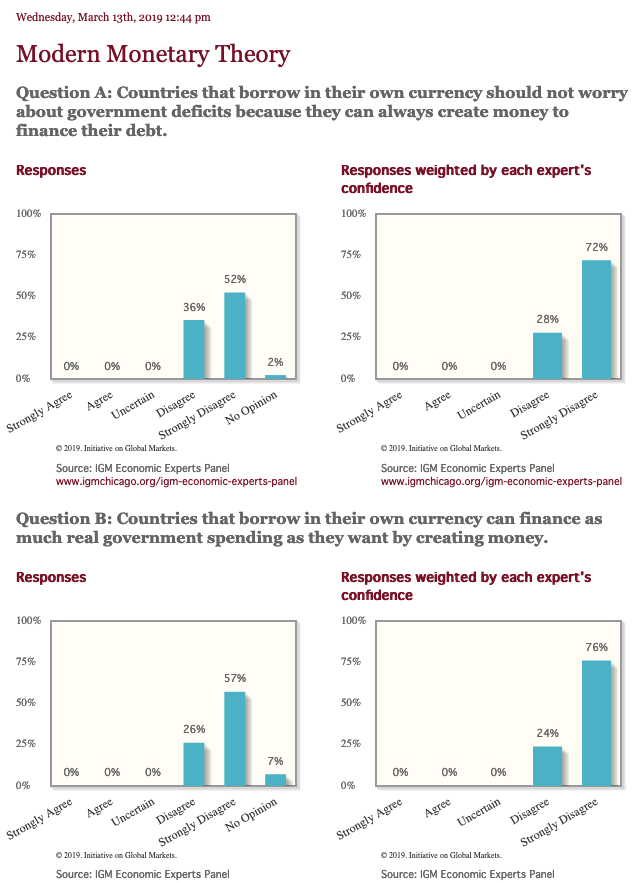

And so, on March 13, 2019, they ran a survey with the title Modern Monetary Theory – leaving no doubt in the respondents’ minds what the topic was about.

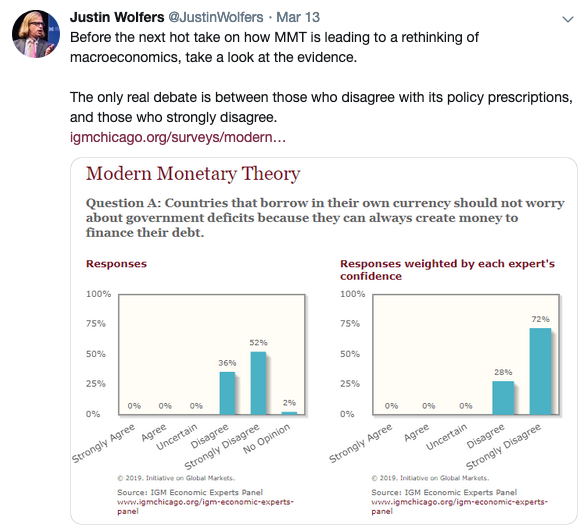

The survey came to my attention via Twitter from an American economist (Justin Wolfers). His Tweet was particularly odious (see graphic below).

He likes to think of himself as a bit of a social media antagonist and has been part of the ‘junior’ MMT attack brigade in recent weeks.

So up pops his Tweet (March 13, 2019) crowing that we should just “take a look at the evidence”.

And that “the only real debate is between those who disagree with its policy prescriptions and those who strongly disagree”.

He linked to the Chicago Booth Survey results.

Now before we look at the results, it should be noted that by his own admission, Wolfers hasn’t taught macroeconomics since 1994 and then it was an introductory course. His main teaching at present appears to be introductory and graduate microeconomics.

He has hardly any publications that one would classify as being about macroeconomics and the most recent appears to be 2005 with a couple earlier than that.

In other words, it is hard to consider him a macroeconomist or a monetary economist at all. Neither his research or teaching reflects any particular expertise in macroeconomics.

Wolfers intervention exemplified Janis’s Groupthink indicators.

He later popped up in an Australian media ‘hit job’ that appeared in the Australian Financial Review article (March 15, 2019) – The magic money tree fix for America’s fiscal malaise.

The article quotes his Tweet (as above) and gets some grabs from him.

Apparently, Wolfers is “mostly irritated by the debate and the way adherents continually move the goalposts of their arguments”. The debate being about MMT.

He told the AFR:

You can probably tell that I’m not a fan … I’ve put in some time trying to figure out what these guys are on about, but at a certain point, if it isn’t clear, I stop blaming myself.

I figure that I’m a PhD economist with a fair bit of experience, and so if I’m not following along, perhaps it really isn’t my fault.

And many of my friends have said something similar – that they find it hard to discern just what the heck the MMT folks are saying.

Groupthink.

I doubt that Wolfers has read any of the core academic MMT literature. It is very clear what we are saying.

There are no goalposts being moved at all.

Wolfers got the ‘goalposts’ bit from Paul Krugman, who tweeted in support of Wolfers claiming that MMTers are always moving the goalposts.

In fact, I would have thought we have been boringly consistent over the last 25 years.

Wolfers also said the people who run the IGM poll were “very smart people” – appealing to authority. They are smart so they must be listened to and they are correct.

The problem is that smart people also fall prey to Groupthink and can exude a basic dishonesty as they toy with remaining members of the group.

Now go back to the ‘Survey’.

In addition to the two questions asked, Chicago Booth also provided this – Supplemental Information on Modern Monetary Theory – which, in fact, said nothing at all about MMT.

They distil MMT down to the proposition that:

… a country that is able to borrow in its own currency need not worry about government deficits and debt

25 years of our work is dismissed and crudely replaced with that piece of nonsense.

Next, look at the questions that were put under the heading Modern Monetary Theory.

Question A: Countries that borrow in their own currency should not worry about government deficits because they can always create money to finance their debt.

I would answer “strongly disagree” to that as well.

Which provides zero information about the validity of MMT.

Question B: Countries that borrow in their own currency can finance as much real government spending as they want by creating money.

Likewise.

At the heart of MMT is the observation that governments face real resource constraints. No amount of nominal spending will reduce that sort of constraint.

It is clear that Chicago Booth has done no research in this regard and the fact that Wolfers chose to spread the dishonesty reflects badly on his ethics as well.

In terms of Question A, deficits always matter and a government has to scale its deficit to the appropriate context.

I have written many articles, sections in books, and blog posts about this point.

A good summary is to be found in this blog post – The full employment fiscal deficit condition (April 13, 2011).

No-one who had read that would pose Question A as being a fair representation of MMT.

Nor would they say the ‘goal posts’ are always shifting.

The appropriate MMT fiscal rule is clear – to sustain full employment the fiscal balance condition for stable national income is that the fiscal balance has to be equal to the saving leakages plus the import leakages (drains) that would occur at full employment income levels less the spending injections from investment and exports that would be apparent at that level of GDP.

If the fiscal deficit is not sufficient, then national income will fall and full employment will be lost.

If the government tries to expand the fiscal deficit beyond the full employment limit, then nominal spending will outstrip the capacity of the economy to respond by increasing real output and while income will rise it will be all due to price effects (that is, inflation would occur).

As I noted in that blog post – MMT specifies a strict discipline on fiscal policy. It is not a free-for-all. If the goal is full employment and price stability then the Full-employment fiscal deficit condition has to be met.

So Chicago Booth’s Question A is simply a dishonest representation of MMT.

It is clear that the core MMT group thinks that deficits matter.

The final point I will make today relates to the claim by Wolfers that he doesn’t understand what we say.

I could make the obvious conclusion despite him touting on his Wikipedia page how he is “one of the brightest young economists who are expected to shape the world’s thinking about the global economy in the future”.

As David Andolfatto, who is hardly an MMTer, wrote in a very reasoned piece (March 14, 2019) – The Chicago Booth survey on MMT:

But it seems to me that some of my colleagues can only understand an argument if it’s posed in their trade language. This is a rather sad state of affairs, if true.

As my work on framing and language has exposed, if a new paradigm uses the frames and language of the old paradigm, we just privilege the old paradigm and its lies.

Conclusion

Groupthink is a very powerful (negative) force in the academy.

This Survey and the way it was promoted by the mainstream economists exemplifies the dynamics of this sort of patterned behaviour.

Think back to the neurogenesis example.

Fake knowledge held on for nearly 30 years after it was exposed and influenced clinical practice (to the detriment of people) because of the Groupthink and the dominance of the key academics in the area.

The same problem cripples economic policy making.

The characters all feel cosy within the group, answering and disseminating fake surveys, and pretending there is no dissonance between what they practice and the real world.

But just like the unfolding undermining of the dominance position in neuro science, the real world is continually delivering negative verdicts about the mainstream macroeconomics.

It is only a matter of time.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Well done Bill and Co

You’re getting traction

What about psychology? Generations of students studied the nonsense called behaviorism invented by B.F. Skinner. They put hungry, thirsty randy rats in cages and tempted them with cheese, water and Mini-Mouse in bikinis. This was supposed to prove something about the relative strength of drives for hunger, thirst, sex. From the rat’s point of view the conclusion was obvious. Human beings in white coats are not to be trusted. Wonderful stuff Bill, Congratulations. This is heroic struggle.

If we add 2 +3 we will get 5.

Here 2 = Dr. Wolfers says he is smart, but doesn’t grok what MMTers are going on about.

And 3 = the Booth profs. thinking they can restate what MMTers are saying and meaning, when in fact (while they are smart) they can’t grok MMT because it clashes with their deeply held dogma.

Therefore, 5 = a bullshit survey.

And this is assuming that there was no malice in their thinking processes.

.

Did the Booth profs. ask an MMTer if their questions were an accurate restatement of what MMTers are saying? NO!!! They did not. Did they get it wrong? Yes. Does all this further their goal of protecting the dogma? Yes.

Was there malice? Who can say for sure? I would assume, yes there was.

.

Also, Bill, 36% + 52% + 2% = 90%, not 100%. That bar graph is wrong somehow.

The “bright” ones leave enough space to say in a few years’ time that they always new MMT was an accurate representation of the real world and that they simply disagreed over some of the detailed policy options flowing from it. It was just a local difficulty. Wolfers has painted himself into a very small corner. Hilarious. Bill, I love that you suggest he writes his own Wikipedia page…. but I must be mindful not to fall into Groupthink here. We’re all vulnerable to it, perhaps especially amateur camp followers like me even though we don’t face the professional/career pressures.

Yes @MattR, I agree that we are all (at least potentially) vulnerable to falling into Groupthink. I haven’t studied it, but I would imagine it goes back to the same sort of instincts that underlie tribalism. At the same time, there are always some individuals who rebel against the tribe – against orthodoxy. Thank heavens for the “awkward squad”.

I like Rupert Sheldrake’s talk where a physicist defined groupthink for him as “Intellectual Phase Locking”

Anyone,

For America would it always be more of a deficit if America passed an Amendment to limit future deficits to 10% of the budget total? Or 10% plus the trade deficit.

My thought is to placate the deficit hawks, by limiting the maximum deficit spending so as to keep hog wild spending in check.

Or will rolling over the national debt someday be over 10% all by itself?

I was not clear. Would 10% always be enough to always be more than we need or want?

Unfortunately we have a mini-groupthink going on in UK – on the left. John McDonnell has just announced a £60 UBI FFS! I blame Positive Money which has infected a good part of those considered left economists here. But there’s no point in dealing insults, Bill. I try to be polite and engage with them. I’m sending JC the book with a note explaining how AOC is on the right side of history. Neither JM nor JC are economists, but JC has not had the disadvantage of listening to ‘the experts’. JM has done a great job of listening to the right people on almost everything else. He’s really not to blame.

Bill,

I think both questions are phrased so terribly that both are probably unanswerable in their current form. But Question B, at least if certain assumptions are read into it, seems to me only to ask whether the government is financially constrained. It doesn’t ask a normative question but a legal/descriptive one. Rewording it slightly, and assuming it is referring to a currency-issuing government’s whose currency floats on an exchange, doesn’t it ask: *Can* a government which does not borrow in foreign currency spend as much money as it wants by creating money? Isn’t Question B then just an (awkwardly worded) restatement of the proposition that monetarily sovereign governments face no financial constraints?

(I don’t understand the presence of the word “real” in Question B, and so I suppose that could matter to the answer. But as far as I can tell the word is superfluous given that the question only appears to ask about financial power.)

Why don’t you (MMT economists) organize a similar poll asking about the things that are obviously wrong with mainstream? For instance: interest rate and inflation in Japan, or even more obvious things like: do banks need savings or reserves before lending?

That would be fun.

@Steve_American

As I understand it, the appropriate deficit is an artifact of the private sector savings and trade imbalances, both leading to insufficient demand to employ available labor and therefore cannot be known in advance. I believe that the premise is that the sovereign should spend whatever is necessary to achieve full employment, and no more; if that required level of sovereign spending exceeds revenues from taxation, the result is a deficit.

But the problem with, as I call them, the “deficit chicken-hawks” is that they prioritize budget balance over citizen well-being and full employment. This is essentially a mental health problem on their part, and their malign influence is damaging the health of their fellow citizens.

Jerry, there is nothing wrong with behaviorism per se. What you are complaining about is what is known as Skinnerian Radical Behaviorism whose canonical text was Skinner’s The Behavior of Organisms published in 1938. Its problem is that it denied that an animal ever thought or had ‘ideas’ of any kind; there were only behaviors and environment, even for humans.

Skinner was once asked why he stopped being the editor of his high school paper. He told the interviewer that they probably thought that he stopped because he had run out of ideas; but that wsn’t right; he hadn’t run out of ideas, because he had no ideas; rather, he had run out of experiences.

This seems ridiculous to us and I thought it was ridiculous at the time, but, then, I had read Edward Tolman’s Purposive Behavior in Animals and Man (published in 1932) and thought highly of it. Radical Behaviorism was only overthrown by a resurgence of cognitive psychology allied to developments in AI (so-called thinking machines). This particular revolution fits Ludwik Fleck’s (Genesis and Development of a Scietific Fact, originally published in German in 1935 and which influenced Kuhn) and Kuhn’s notion of a scientific revolution. However, unlike physics, experimental psychology was rediscovering its non-radical behavioral interpretation of the nature of animal behavior.

If we go with this motif, MMT is the alternative paradigm that is providing food for the ‘revolution’.

Bill’s insightful observations into Groupthink, not only in economics but in other fields as well, indicate we are dealing with what is essentially an ethical problem. When, for example, “real criticism of the central bank has become a career liability for members of the profession,” then those economists, who cannot help but see problems with the central bank, are faced with a fundamental choice: to pursue their careers by keeping silent (the wrong thing) or to pursue truth as they see it, at whatever personal expense, by voicing their concerns (the right thing). Some form of denial, what the existentialists call bad faith, is the usual upshot of this dilemma. At its most elemental level, is not neoliberalism the wholesale abandonment of ethics in favor of advantage, at least for the elite?

Addendum:

There was what might be considered a reductio ad absurdum of the Radical Behaviorist view in the work of Clark Hull. He considered that the S-R connection so beloved by Skinner was too simple a framework. So, he advocated introducing a sequence of little s’s and little r’s connecting the big S and big R of the standard Radical Behaviorist framwork. So, we then had intermediate stimuli and responses, a little s(g)-little r(g) goal response chain inside the organism connecting the initial Stimulus and the final Response.

It was very clever and viewed as an improvement. It was developed in the context of Hull’s drive theory and was seen by him and others as being scientific. This was in line with Skinner’s claim to be proposing a scientific theory, something he believed his predecessors had failed to do. However, though Skinner contended his theory to be structured around testable observables, the same could not be said for Hull’s little s(g)-little r(g) goal response chains.

In addition, Hull thought that a machine could be constructed to mimic human thought processes. This is in line with Skinner’s view that there were no such things as thoughts per se and the development of Hull’s own theoretical approach. While he carried out this work in the forties, which was when his book, Principles of Behavior, came out, it was another ten or so years before the theory came to be seen to be inadequate.

Newton Finn, I expect Samuelson, were he around, might agree with you, as he claimed that he advocated his neosynthesis classical Keynesianism in order to contain spending as it could so easily get out of control.

eg,

Yes, I understand that the target for ethical Congress-persons is full employment with little inflation. [I think 2% is seen as about right.]

But, deficit hawks worry about what happens when the voters grok that they can tell their Congress-person to vote to give them all a big handout and they win elections. So, that is what Congress does. And, MMTers would say that that will cause larger inflation.

Yet, this is a likely outcome according to deficit hawks because the voters are too self-interested to care.

My question was, is there an upper limit that can be defined?

I see the trade deficit as one part of it.

I see rolling over the old bonds as another part, right?

And you pointed out that savings desires is a 3rd part.

.

I have been told by prof. MMTers that they don’t care what deficit hawks think. But, I think that there are a lot of them in the electorate and they vote, so isn’t it better to address their concerns? If my idea gets a million of them to stop voting to block Progressives who want to use MMT more, isn’t that a good thing. At least if some upper limit can be defined and binding promises made to not exceed that limit.

As a Monetary Reformer in support of the NEED Act and and a Green having dealt with an MMT attempt to take Monetary Reform out of our platform, calling us cranks, trolls and conspiracy theorists and knowing that it has been common practice for MMT proponents to censor critiques posted in the comments I think this is rich, the 8 characteristics of Group Think apply pretty well to MMT. That is unfortunate becasue it seems most supporters of MMT want the same spending on the Green New Deal etc. etc. as Monetary Reformers do. But, the law has to be changed in order to do so and the same Congress elected and willing to do that spending will have no problem changing the law to allow Government to create money without incurring debt to the banking system or bond holders. It does not put any banks out of business, they just must operate as most people believe they do now, that is loan existing money. The fact that the Constitution gives Congress the money creation power does not mean that it does becasue “operationally” the Constitution is being ignored on many levels.

Steve, if you are asking whether there is an upper limit, say, in terms of a percentage or a figure, there is none. All upper limits are conditional on the states of certain other factors, such as the level of unemployment. The war suggested that full employment was around 2%, so it might be possible to mention something like that. But it might be countered that those were exceptional circumstances. In any case, there is no single upper limit that can be unconditionally specified.

As for the deficit hawks, it may turn out that there is nothing you can do to assuage their concerns, as these might be a bottonless pit. You may be forced to a conclusion that your only option is to try and outmaneuver them rather than trying to bring them over to your side.

Do we know why the mainstream people say that they strongly disagree with question A.

The thing is, MMTers would disagree with Q1 on the basis of real resource constraints.

Do mainstream people disagree on the basis of that, or rather on the basis that they still believe money is a constraint.

“But, deficit hawks worry about what happens when the voters grok that they can tell their Congress-person to vote to give them all a big handout and they win elections.”

I repeat, please read Caitlin Johnstone’s continuing essays about narrative, and holding power by manipulating narrative. The passage above is narrative, and it argues that Responsible Government has to be ditched because it would be irresponsible, and that democratic government can’t work. It might be true, and then we’ve all had it; otherwise, where did it come from? And how would we control it, assuming we can?

larry,

I assume that there is an upper limit. I can guarantee that it is less than 100% of the budget, because then there would be no tax revenue to give the dollars their value.

So, coming down from that maximum level of the budget, can you imagine ever seeing the deficit (that is the proper deficit for prof. MMTers) being 70% of the budget? 60%, 50%, 40%?

Mel,

That sentence came out of my own mind. I don’t talk to a lot of people and have had few friends compared to the average, so I don’t think it came from a friend.

Bill,

One positive outcome of the GFC should have been that the mainstream economists then had a chance to come out of their complacency, reevaluate their failing predictions and economic models.

That this did not happen, and to your point, only shows what kind of an echo chamber they are working within.

Steve,

Sorry. It wasn’t your statement that deficit hawks worry that worried me. It was what the deficit hawks worry about that’s the narrative I’m scared of.

I misspoke, or misquoted, or something.

Tom @1:15 , “Do we know why the mainstream people say that they strongly disagree with question A?”

Not really. There was some (apparently very limited) area in the response ‘form’ where the surveyed economists could attempt to explain why they chose to disagree with the statement. Not all of them utilized that option though. None of those who did reply used that area to explain that MMT itself would not agree with the statement as actually written. But some of them did write one sentence blurbs that could be interpreted (if you were feeling charitable) as understanding that while there are not nominal constraints there are still always real resource constraints.

So the statement is “Question A: Countries that borrow in their own currency should not worry about government deficits because they can always create money to finance their debt.” David Andolfatto in his linked post corrected this to reflect more realistically what an MMT economist might actually say-

“O.K., so let’s consider Question A, where some legitimate confusion may be present…

“Alright, so on to the question of whether deficits “matter.” The more precise MMT statement reads more like this “A country that issues debt denominated in its own currency operating in a flexible exchange rate regime need not worry about defaulting in technical terms on its outstanding debt.” That is, the U.S. government can always print money to pay for its maturing debt. That’s because U.S. Treasury securities represent claims for U.S. dollars, and the government can (if it wants) print all the dollars it needs.”

“Nobody disagrees with this statement. MMTers like to make it explicit because, first, much of the general public does not understand this basic fact, and second, this misunderstanding is sometimes (perhaps often) used to promote particular ideological views on the “proper” role of government.”

Good for David Andolfatto for calling out this sham survey of supposedly MMT ideas. I have to say I was very surprised that he did it- but he did it none the less, and that should be (and Bill has) recognized.

I think there is a way to interpret Question A to answer it affirmatively, but the question is just so poorly phrased that it’s best left unanswered. It turns on what it means to “worry about government deficits,” which is a horribly imprecise thing to ask any alleged scientist. But I think it’s true that monetarily sovereign countries (which is what I interpret the bizarrely phrased “countries who borrow in their own currency . . . [and who] can always create money” to mean, although this omits the exchange rate policy) need not “worry about government deficits,” if this only means it need not worry about the nominal amount of the deficit; however, to be true this requires the government to be minding inflation. The question is silent about whether the government in question is doing that or not, but if one assumes it is, then the proposition is correct as far as I can tell. I don’t think a monetarily sovereign government should care what its deficit is if it is net spending an amount that keeps the economy operating at capacity with stable prices.

Steve, what gives the national currency its value is the government itself, not taxation. The functions of taxation are other than giving value to the currency. You can check Ruml’s “Taxes for Revenue are Obsolete”. The deficit has been higher than 100% for long periods without the sky falling in when the government is operating a fiat currency system with a flexible exchange rate.

Oh the irony! All of those group thinkers behind the “rational man” believing they actually were that man, and for so long! It leaves one wondering how long it would take for them to begin recognizing the error in their ways without the work of the core group of MMT scholars? Three cheers!

I just looked at the questions again, JT.

I think that people should just learn MMT. Mainstream language is just imprecise as you said and it is also incorrect.

Borrowing implies you are getting something you don’t have to spend it now, and you will have to repay later.

Reality is nothing like that.

Anyway, I would put disagree on both questions also.

Survey the New Keynesians’ views about this statement:

“Maintaining a fluctuating pool of unemployed, underemployed, and precariously employed people is the most humane and economically efficient way of stabilizing prices.”

@Steve_American

Here in Canada our Federal Government just tabled a budget that changes the narrative about deficits as leaving a burden to our children to one of investing in our collective future:

“In his final budget before an expected vote in October, Finance Minister Bill Morneau stressed the need for government “investments” over reducing the deficit. Before Tuesday’s budget, stronger tax revenue had Ottawa on track to substantially reduce the federal deficit over the short term, but the government chose instead to announce billions in new spending over six years.”

They will be pilloried by the usual suspects in the press and on talk radio (listening to which is a vice I cannot seem to shake, though listening to the moron callers and the demagogic hosts causes me to swear out loud whilst driving my car) but the litmus test will be our Federal election in October. If the Liberals (a center-left party in Canadian terms, but outright leftist in US terms, since even our “right-wing” Conservative Party of Canada is at least pinkish in US terms) can return a majority government, it may well serve as a death-knell for Canadian deficit chicken-hawks since it will mean that the populace will have repudiated the deficit concern-troller narrative.

That our Canadian Liberal party is prepared to stake the outcome on the upcoming election on a platform of intentional deficit finance gives me some hope, though the proof of the pudding, as they say, will be in the eating (ie. in the actual election outcome in October)

Will similar attitudes ever prevail either in Australia or the USA? I certainly hope so!

Sorry for posting back-to-back, but I forgot to leave the link from which the quote appears in my prior post (I hope posting a link is not in violation of norms hereabouts):

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-federal-budget-2019-liberals-unveil-23-billion-in-new-spending-aimed/

I find most economist become ‘stuck’ When you pose the question ‘Where does money come from?’ They may begin outlining how loans create deposits. True.

How are reserve balances added to? Where do financial institutes obtain currency to buy bonds? How can spending on something that is idle (unwanted by the market) be inflationary?

There are limits but its not some useless fiscal target!

Larry: Steve, what gives the national currency its value is the government itself, not taxation. The functions of taxation are other than giving value to the currency.

That is wrong. Steve is basically right. A major function of taxation in any country today is to give value to the currency. Taxes drive (the demand for) money, state money is a tax credit are two MMT ways of saying it. The government merely saying that its money is valuable is not enough. There has to be some scarcity of money due to demand driven by taxation, relative to availability of money, driven by government spending.

You can check Ruml’s “Taxes for Revenue are Obsolete”. The deficit has been higher than 100% for long periods without the sky falling in when the government is operating a fiat currency system with a flexible exchange rate.

The more usual measure of deficits is as percents of GDP. But Steve talks mainly about percent of the government’s budget, spending above. Then it cannot be more than 100%, which is the limiting case when there is no taxation at all for that year. You probably mean the debt/gdp which can be and often is over 100% for long periods.

Though of course I do not think it is a good idea to have any limitation, 10% would ordinarily be pretty high as a deficit/gdp. For the USA it was only that high recently in 2009, it had been under 5.2% since 1946. The peak WWII deficit in the USA was 27%/GDP.

But 10% would be much too low as a deficit/budget figure. As percentages of the budget outlays, the Hoover Great Depression deficits and early New Deal deficits were over 50%; the peak for this figure was over 70% during the war, in 1943.

venji,

I’d like to take a stab at answering the questions you asked there.

1] In the beginning on the evening of the day Nixon took the world off the gold standard and made the dollar a fiat currency, there were some dollars already in existence left over from the gold era. Also, some T-bonds in dollars.

2] This supply of dollars was added to in 2 ways.

. . a] Banks make loans that create “bank” dollars. When the borrower spends those bank dollars and they are therefore deposited into a different bank, the Fed. Res. bank uses only “reserve dollars” of the original bank to settle the check. The new bank therefore has more reserve dollars but the original bank has less reserve dollars in its account. It seems here that the number of reserve dollars is not increased by this loan, see below.

. . b] The US Gov. deficit spends and creates reserve dollars. This is because after it spends it sells T-bonds for reserve dollars. After both transactions are complete someone has the reserve dollars the Gov. spent and the Bond holder has reserve dollars in his bond account. But, before the 2 transactions only the final Bond holder had any of the final reserve dollars, the Gov. created the reserve dollars it spent. Over time the Bond holder will be paid back with his original reserve dollars and the interest in newly created reserve dollars.

. . . In the meantime, every business night all the banks and the Fed. shuffle dollars around. All the checks and other payments are settled with only reserve dollars. If any bank is short of reserve dollars [to meet the requirement to have 10% of total deposits in the bank, in deposit by the bank in its acc. at the Fed.], then it borrows on the ‘Inter bank overnight loan market’ to get enough reserve dollars to meet its requirement.

. . . In a] above, I left it with the 2 banks having switched some reserve dollars around. Adetailed example is that one day the 1st bank makes a loan of $150K to one of its depositors. If we falsely assume that the reserve requirement is in effect that night [and not delayed for a week or so] then that morning the 1st bank had $400K in reserve $$ in its acc. at the Fed. and the 2nd bank had $300K with the Fed. At 4pm the 1st bank had its $400K at the Fed. + the $150K of the loan in bank dollars on deposit; and the 2nd bank still had its $300K at the Fed. and an un-cashed check for $150K from a supplier to the borrower. By 8am the next morning, the 1st bank had zero new bank dollars on deposit (change =0= +$150K -$150K) i.e., the same total deposits it had yesterday morning and just $250K at the Fed.; and the 2nd bank had its $300K at the Fed. in reserve dollars plus the $150K of reserve dollars from the check, for a new total of $450K in reserve dollars at the Fed. But, it now also has $150K of additional deposits.

. . . In summary, before the loan total reserve dollars = $400K + $300K = $700K and total $$ on deposit = $X. The next morning tot. reserve $$ = $250K + $450K = the same $700K at the Fed.; but there are now $150K +$X total dollars on deposit at the 2 banks. These new $150K now allow $1350 more in additional bank loans by the 2nd bank.

. . . Final outcome is that the loan doesn’t change the total reserve dollars in the banking system but it did add $1350K more possible loans by the whole of the banking system.

All new reserve dollars are created by Gov. deficit spending plus the interest it pays on bonds.

Thank you Some Guy, for your support on that taxes give fiat money its value.

And for the numbers for the limit question.

So, the are 3 possible situations with 3 different limits.

1] Normal times. About 10 to 20% max.

2] Great Depressions and Recessions. About 50% max., but could be higher with a super majority in Congress.

3] When World Wars are ongoing. The sky is the limit.

Now I remember where I got the idea from. It was my ex-sister-in law who was a good progressive Dem until she got divorced and remarried to a fiscal conservative Repub. Years later we were still friends as her children were my niece and nephew. She became a Repub too.

Around 2013 I tried to convince her that MMT makes sense. I failed. Somewhere along the line she may have planted the idea that we can’t let deficit spending go hog wild just because the voters are stupid enough to demand excessive spending.

I still think that a normal times limit of 10% of the BUDGET plus the total trade deficit is a reasonable accommodation to get 1M deficit hawks to vote to support the use of MMT to fund a JG and a GND program.

But, I seem to be very much naive. I want Progressives to march in the streets between now and Nov. 20202 to show the world that we have the numbers to win the election with the Green Party no matter if the Dems and Repuds separately oppose us.

eg,

It is good to see one nation that gets MMT is the way to explain thing to the voters.

BTW — here in America “tabled” in Congress means to stop moving a bill forward.

It seems in Canada “tabled”means to put a bill forward to start debating it.

If money is the point system for economic contribution, then spending should be enough to award all the points earned.

Just try not awarding points for goals in AFL because there are none left.

Or not measuring your height because we ran out of centimetres.

The deficit is just the measure of private savings, usually seen as a good thing by the deficit hawks.

These guys are simply gaslighting and there really is no pleasing them. Engaging with their incoherence will only lead to madness.

Thanks Larry. I should be battening down the hatches for Cyclone Veronica but this is more fun. An interesting research finding from the psychology of learning was that the stuff kids are taught in their typical undergraduate years (late teens, early twenties) does stick in their brains. When the stuff doesn’t tally with the real world it can be hard to digest. In Australia this conflict came to a head at Sydney University with the fight between the economics department and the political economists led by Frank Stilwell. This is the core problem for the traditional religions such as Christianity in a world increasingly sophisticated in its knowledge of science and technology. The Christians need an abstract concept of God.

In his recent podcast from Scandinavia (I think that’s where he was — he gets around so much), Bill Mitchell concluded that MMT would be in place only when it was accepted in the academy and that was a long way down the track. The mainstream has so much invested in dynamic stochastic general equilibrium. People don’t like to admit their mistakes.

At the more prosaic level of Australian politics we see the same game. Opposition leader Bill Shorten is clever and politically astute. Union leader Sally McManus is the only figure in our public life who gives the impression she knows what she is talking about on the subject of neoliberalism. Bill hopes to shift the centre to the left without frightening the horses. I don’t think it is possible. The horses will have to be yarded up and saddled.

Jerry, concerning the horses, I think you may well be right. My impression is not unlike yours, I think, they don’t know what they need to know and they don’t want to know it. Hence, they will resist. It is good to know that some in Australia know what they are doing. I am afraid that this may not be the case in the UK.

So much of MMT is just descriptive. What little minds so many intellectuals have. Or rather, the lust for wealth, power, success, corrupts. People should never forget that the qualities that make for real achievement have more to do with morality than intellect.

People,

The bottom set of graphs the left one totals to only 90%.

Is this evidence of duplicity or stupidity?

The numbers are 26% + 57% + 7% = 90%. Not 100%.

Were those missing 10% of responces all on the agree side? Strongly or other wise?

So is AGW potentially a case of groupthink gone wild ?

I’m agnostic as I am not well enough informed but it certainly seems possible given the vested interests and religious level fervour and shouting down of dissent

This particular argument bill makes seems to be fallacious: Basically the inverse of “appeal to authority”

Jules,

A really big difference between the 2 cases [MMT & AGW]is that climate science is a science and macroeconomics is NOT. Macroeconomics is not a science for 3 reasons.

1] It is unable to do controlled experiments. although Astronomy and Climate science also suffer from this problem to some extent.

2] As Bill very recently pointed out graduate students in macro economics do NOT think that knowing how the economy works in reality is useful for them getting their degree.

3] Economics has for decades used formal logic to ‘prove’ conclusions, which would be fine except many of the assumptions or premises they use are clearly false. [For example, “Every seller and buyer in a market has complete knowledge about every aspect of the thing being sold.” And, that, “It is OK to factor out banks, credit, and money from the model because banks just lend their depositors money to their customers”; but in fact banks create new money when they make loans.]

Are there similar things that can be said about climate science that show it is in groupthink?

Bill had reasons why you can see groupthink in action by MMT critics. Things like, they refute things that MMTers do NOT say. And they don’t site the whole of the literature.

.

Now, it s possible that climate science (CS) has fallen into groupthink. OTOH, I recently saw a liberal claim that all the 3% of CS-tists who doubt it can be linked to The Heritage Foundation which is linked to the oil industry. I have no idea if this is true.

Thanks Steve-American

I think at least number 1 is false for AGW as well

We can’t run controlled experiments on the environment (there is only one environment after all)

It’s all post hoc observations

Macroeconomics is actually probably slightly better in that regard

Certainly all the Irving Janis criteria for groupthink fraud are fulfilled

viciously crushing any dissent is anathema to the philosophy of science and paradoxically raises suspicion

Better to say “we can’t be certain, but even if it’s only a chance the consequences of doing nothing are so great that we should logically act”

Than to frankly lie, which is what is done now

Jules,

CS-tists do lab exp. on the specifics, like how does methane absorb infra-red light.

Economics can’t even do that.

CS do a lot of supercomputer models.

Economics doesn’t do that either, IIRC.

CS are getting emotional because they have been ignored for 25 to 30 years, while the science got better and better. They are getting strident because the stakes are so high.

The only ones I have seen being “certain” are the ones like McPherson who says it is too late anyway. Where did you get the idea that CS-tists are positive? Foxnews?

Both climate science and macroeconomics are engineering-like subjects in that they address the behaviour of highly complex and inter-related systems of systems. The value of doing “controled experiments” on such systems is highly over rated, cf recent 737 max affair to appreciate the limits of testing based analysis. The adage that “it is difficult to predict, especially the future” was aimed directly at this situation where there will never be enough data in to even narrow down the functional behaviour of such a system.

Both disciplines respond to this challenge by performing actual controlled experiments (small number of variables believed to be related by an easily parameterised family of casual interactions) on small subsystems and using mathematical synthesis to infer or deduce the overall beviour function from the perceived inter relationships between subsystem instances.

The problem with macroeconomics seems to me to be an unwillingness to take on the hard mathematics of complex nonlinear (hate that word) systems, instead opting too often to want to simply “scale up” the character of subsystems or adopt ludicrously simplistic polynomial function based models.

The difference between the two lies in the massive computer modelling efforts of the climate scientists, borrowed from the amazingly successful field of weather modelling.

That said, all you really need to know about the CO2 based greenhouse effect lies in the controlled experiments that determined that CO2 absorbs infra red spectrum radiation. This makes CO2 a big player in climate related atmospheric behaviours. Performing a massive scale experiment as to the effect of increasing CO2 concentrations at an exponential rate is obviously foolhardy and will likely not give repeatable results.

Brendanm,

I can agree with all there except that macroeconomics can make meaningful small scale actual experiments. I don’t think it can.

Your point about nonlinear math is right on point. I read about it when it was called Chaos theory.

But, my main point needs emphasizing. Namely that econ students are not taught that REALITY is the touchstone of the ‘thing’ they are studying and will be trying to predict someday. Economics teaches them to ignore reality and study their models. This is necessary for the students to be able to accept false assumptions like the examples I gave above.

. . . But, all REAL sciences study reality and they don’t allow false assumptions to underpin their models without pointing them out and showing why they are justified. An example of this is the ‘rigid body’ assumption in engineering which assumes that the pieces of a girder bridge (etc.) do not bend or change shape under the forces that are placed on it.

“The other problem was that the survey respondents were too insular (I didn’t say stupid) to realise they were being duped by Chicago Booth.”

Allow me to say it then- insular to the point of stupidity in this case. It is stupid for someone who calls themselves a professional economist to be so insular. And then to answer poll questions asked of them because of their ‘qualifications’ if they are ignorant. Once in a while you are too nice Bill.

I really enjoyed this post, Bill. Mainstream economists have emerged from proud silence to take on MMT for the first time, with little homework. It’s a target-rich environment that you’re exploiting relentlessly, persuasively, with dignity.

It’s exciting to witness an intellectual paradigm shift like this unfolding day by day.