My friend Alan Kohler, who is the finance presenter at the ABC, wrote an interesting…

Australian Senate enquiry finds that the university sector is rotten to the core

Last week, the Education and Employment Legislation Committee of the Australian Senate (our upper house) released its interim report – Quality of governance at Australian higher education providers. It wasn’t pretty reading. Those who work inside the higher education system could have written this report some years ago – given the problems that are finally being made public have been endemic to the system for years. As neoliberalism infested all the areas of our society, higher education has been transformed from a high-quality institution providing first-class education and research excellence into a confused, underfunded and dysfunctional sector. Meanwhile, the political class, including those elements that took the revolving door and went from Federal ministerial positions to taking over university management, are denying their involvement and wanting more destructive changes, dressed up as ‘reforms’. Reform is a good outcome in my lexicon. More neoliberalism doesn’t constitute reform.

MORE

The Senate Enquiry sought to investigate various elements of university governance, compliance with the existing regulations including workplace laws, the standard and accuracy of financial reporting, and executive remuneration and the use of external consultants.

Basically, from years of working in the sector, these are my brief conclusions to each of their Terms of Reference:

1. There is now a lack of transparency and accountability by governing bodies of our universities.

2. Individual universities do not always comply with the legal requirements.

3. Many institutions have been caught underpaying staff against workplace rules.

4. There have been regular financial scandals – junket trips by senior management.

5. Top management is ridiculously overpaid right across the sector, while casualisation at the lower ends is rife.

6. The use of incredibly well remunerated external consultants is endemic and usually not worth the funds spent.

But let me take to you what the official Senate Enquiry has found.

The Chair of the Enquiry was quoted in the media as saying upon release of the Interim Report that Australian universities have developed a (Source):

… culture of consequence-free, rotten failure …

These failures have contributed to damaging restructures, job losses, wage theft as well as a growing sense of abandonment among students and distrust within university communities …

There’s no other sector in the country where failure is rewarded so handsomely and with so little scrutiny.

Now when we talk of rewards it is not the salaries of the more junior academic staff that we are talking about.

Australia has 44 universities of which 39 are public institutions and 5 are private.

The Interim Report found (using evidence from external submissions) that:

1. “there are now 306 university staff across Australia who are paid more than the premier or chief minister of their state or territory.”

2. “vice-chancellor salaries … appear to bear ‘little to no’ relation to university size, international ranking, or financial performance'”.

3. “Vice-chancellors and senior executives in Australian universities command exorbitant salaries that are increasingly misaligned with both public expectations and institutional performance.”

4. “Australian university vice-chancellors are ‘among the highest paid in the world’, with salaries more than quadrupling since 1985.”

5. In 2023, “the top twelve vice-chancellor salaries were:

– University of Canberra – $1.785 million;

– Monash University – $1.565 million;

– University of Melbourne – $1.447 million

– University of New South Wales – $1.322 million;

– Flinders University – $1.315 million;

– Queensland University of Technology – $1.235 million;

– University of South Australia – $1.235 million;

– University of Sydney – $1.177 million;

– University of Queensland – $1.162 million;

– University of Tasmania – $1.115 million; and

– Australian National University – $1.1 million.

6. “A further nine universities paid vice-chancellor salaries in excess of $1 million, with the remainder paying salaries between $652,000 and $975,000.”

7. “vice-chancellor pay has grown faster than average Australian worker earnings and income support for students”. In real terms, the top paid VCs have seen their annual salaries rise from $A300,000 in 1985 on average to $1,250,000 (around in 2023.) while average annual earnings in the economy have been static.

8. “in 1985, an average vice-chancellor at an elite research-intensive university was paid 3.1 times more than an early career lecturer. However, by 2022, vice-chancellors were paid more than seven times as much as university lecturers.”

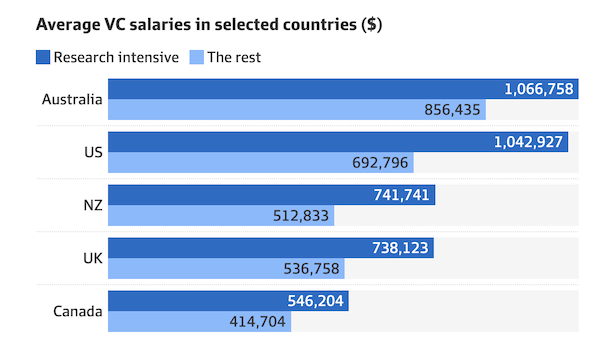

9. An article in the Australian Financial Review (January 25, 2024) – Are Australian university bosses worth the big bucks? – found that Australian VCs are paid much more than their counterparts in the UK, US, Canada and New Zealand.

The article provided this graphic which was reproduced in the Interim Report:

10. “the contrast between high vice-chancellor remuneration and the casualisation and underpayment of other university staff was stark.”

11. There is also a layer of executives below the VC rank who binge on massive salaries and their numbers have been rising relative to total academic staff numbers – there has been an “unprecedented increase in senior and middle management positions’ over the past two decades represented a shift toward managerial expansion …”

Of course, the defenders of this system claim that increased complexity and the need to attract the “best and brightest” to run our institutions is the reason for the pay explosion.

I can tell that that sort of justification doesn’t stack up when we assess it against the performance of our higher educational institutions.

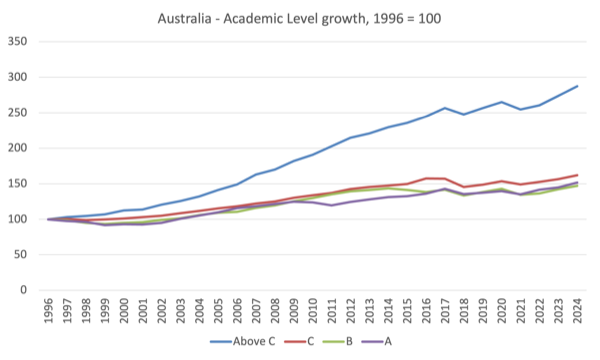

The following graph shows movements in indexes (1996=100) from 1996 until 2024 of the employment of different academic ranks in Australian universities.

The latest data is provided by the Federal Department of Education – Selected Higher Education Statistics – 2024 Staff data.

Academics in Australia are ranked E professor, D associate professor, C senior lecturer, B lecturer, A associate lecturer.

Level A is Associate Lecturer – the old tutors rank which was really an apprentices job to help subsidise doctoral studies.

The academic union some years ago became beguiled by management-speak and agreed to incorporate the tutors rank which was outside the tenure system into the main structure – for a pittance of a salary increase.

The upshot – previously Level B Lecturer was the entry level after PhD.

Now the entry level is Level A and it forces PhD holders to spend longer at the lowest levels – which was a plainly stupid error by the academic union – one of many.

Level A and Level B are thus the junior ranks and shoulder a heavy teaching and administration load.

There is significant casualisation at these levels.

The Department of Education data shows that in 2023, 64.7 per cent of teaching only staff were casual; 6.2 per cent of research only staff; 2.1 per cent of teaching and research staff; and 9 per cent of ‘other’ staff – support, technical etc.

Level C is the Senior Lecturer which was in the past the “career” position to aim for and very few academics went beyond that and one was considered to have succeeded if they retired as a Level C.

Level D is Associate professor which became the aggregation of the old Reader and Associate Professor positions, the former being awarded for research excellence while the latter was usually handed out for some beyond the call commitment to senior teaching and administration without the person having much of a research track record.

Level E is what we call a Professor here or a Chair holder. In the US, they call this person a Full Professor – Level E is the highest academic rank attainable in Australia.

To attain the position of professor in an Australian university one used to have to demonstrate that they had achieved an international level research record to a rather demanding appointments panel made up of people external to your University as well as senior insiders.

This was typically demonstrated by an extensive publications list and a significant record of research grant success from national competitive funding sources and elsewhere.

Other achievements were also required – quality doctoral supervision outcomes etc.

So because it used to be an onerous process, very few people became Level E appointments as a result.

That is, until now.

Professors seem to – grow like Topsy – and all sorts of corporate types, ex-politicians chasing a sinecure, etc are hired as Level E and assume management roles.

The VCs and senior executives are all ranked at E with some rare cases being at D.

In terms of the graph, while the total series has moved from 100 in 1996 to 174.2 (in index numbers) in 2024, the Level E and D category has grown from 100 to 287.4 points.

Starting at 100 points in 1996, the employment number has risen by 2024 in index number terms to:

– Above Level C – 287.4 points

– Level C – 162.0

– Level B – 147.3

– Level A – 151.8

– Total – 174.2

Student-staff ratios have risen and more slog work is being pushed to the lower ranks that have not maintained proportional growth.

Meanwhile the hugely overpaid senior staff are growing in numbers both absolutely and relatively.

The Interim Report also found that senior management of our universities binge on external consultants.

I can tell you that this has been going on for years and in my experience the consultants rarely understand the workplace or the mission of the institution.

I recall one time when I was a member of the University IT Committee that an external consultant asked ‘why would an academic want a portable computer, they are hugely expensive’.

I felt like responding with ‘duh’.

But …

I could disclose countless examples of consultant idiocy but highly paid idiocy – but because those matters were confidential I won’t.

The Interim Report found that:

1. There were “concerns about the transparency of council decision-making and university finances (including the use of consultants)”

2. It was difficult to ascertain “the specifics of spending on consultancies” and

3. There was the “The potential for conflicts of interest to arise via the movement of senior executives between universities and consultants”.

4. “External consultants are usually engaged, presumably to create the impression of impartiality, but final decisions from these investigations almost always fall to the university’s governance officials.”

5. “Conflicts of interest are rife, and millions of dollars of public funding are being poured into private consultants rather than into our public education.”

In general, Australian universities have become ‘black boxes’ with poor transparency and accountability.

The regulator has not been provided with sufficient capacity.

Staff in the universities are not consulted on major changes in an adequate manner and have been progressively excluded from key decision-making committees.

The VCs and senior executives are ridiculously overpaid and the Report wants to rein that in.

University councils, the ultimate decision makers, are stacked with people with little public administration experience or “higher education expertise”.

Any old corporate networker seems to be able to get on a university council somewhere.

etc.

We can trace the development of all these problems back to the beginning of the neoliberal period.

We were told that universities had to become like corporations and so they did, except the acid test that corporations have to meet (that is, they have to sell something at a profit), is not at all applicable to a higher education institution and trying to impose corporate (profit) like Key Performance Indicators (KPI) on a university is nonsensical and begins the process of deterioration which is now being exposed.

In Australia, the obsession with fiscal surpluses at the federal level and ‘competitiveness’ has seen universities underfunded and corporatised.

And they have become hollow semblances of what they used to be.

But the politics is all about more neoliberalism not less.

A former federal Labor leader and senior minister recently retired and didn’t take up golf.

No, he moved into the higher education sector and took over as VC of the University of Canberra and probably doubled his salary.

His university is lowly ranked yet is paying him around $A860,000.

On September 18, 2025, he gave a speech – Higher Education in an Age of Disruption – which is being held out as a blueprint for reforming the rotten higher education sector in Australia.

He wants to scrap 3-year degrees and replace them with “modular” arrangements – he used the example:

Imagine a defence industry worker in Adelaide. They don’t have three years to learn about quantum mechanics but they have a wealth of skills and experience and 4-6 weeks to complete a micro-credential co-designed with industry and defence to fill identified gaps.

Hmm, one should be able to pick up quantum mechanics in 4-6 weeks.

Piece of cake.

Macroeconomics in 2.

Brain surgery in 1 – pass the saw bud!

etc

He wants the higher education system to be:

… co-funded by government and industry, where companies in the health, defence technology, and resources sectors directly subsidise the micro-credentials they need, would remove the debt burden from the individual.

Two points:

1. The “debt burden on individuals” is because of the fiscal surplus obsession and the ‘user-pays’ ideology.

Students in the pre-neoliberal era didn’t have to endure that burden.

2. The idea of ‘co-funding’ is a long-held neoliberal principle – Public-Private Partnerships, etc – most of which have been spectacular failures.

And privileging private profit in curriculum design is a recipe for disaster.

We should prioritise our universities with the task of creating basic knowledge and if corporations want staff to be specifically-skilled then they should do that on their own time and expense.

He also wanted more commercialisation of research.

This is a large topic but my position is that universities should do basic research and leave the commercialisation to the corporations.

Conclusion

I could write much more on this topic but I have run out of my allotted time today.

This week I will pop up in Japan – more tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’d blame students just as much as anyone else for placing far too much importance on what a degree did for them financially rather than academically.

In my limited experience teaching university students it was always for them about the qualification / certification, and not the skills or knowledge.

As someone with a love of learning and absolutely zero interest in making money I find it all rather heartbreaking – but in no way surprising where things have ended up.

Bill’s post on this Senate Enquiry coincides almost to the same day in September that I handed in my resignation at Flinders Uni ten years ago.

I finished my PhD in 1997 and, being an Adelaide boy, I wanted to secure an academic position in Adelaide. Academic positions in my area are few and far between, and so I was fortunate that one popped up at Flinders just as I was entering the market.

I felt, at that point, that all the stars were lining up for me. When I returned as an undergraduate student at Flinders in the late 1980s, the system was still in good shape, although some of the Dawkins’ reforms (reconfiguration of higher education in Australia) had just been introduced. My lecturers were generally very good, notwithstanding the mainstream flavour of the economics. Bill was at Flinders at the time. I had him for Statistics A. He stood out like a sore thumb. He’d delve into the economics during the topic and it seemed at odds with what I was being taught in other subjects. My politics and geography lecturers were first class. I did Politics 1 in first year and a geography major as part of my B.Ec.

I returned as an undergraduate as a 23 year old. I had saved a little bit of money. Together with AusStudy, I was able to study full time and not have to spend precious time doing a casual job. Looking back, I was fortunate to have studied when I did.

I was fortunate enough to do well in my Honours year and decided to do a PhD. I applied for a Commonwealth Government scholarship and was successful at securing a ‘priority award’ scholarship, which was more generous than a standard award. I did some casual tutoring while doing my PhD and saved enough money to put a deposit on a house when I got the position at Flinders in 1998.

Despite ongoing changes to the Australian sector, I still felt privileged to have the position I had. My colleagues were very supportive of me and I received some generous teaching concessions from time to time to spend more time on research.

In 2007, the School of onomics merged with the School of Commerce to form the Flinders Business School (FBS). Until then, the Head of the School had been democratically elected by the School staff. The same applied for the Faculty Head until 2005. Now every senior management position was an executive appointment chosen by a team of very senior head-kickers and bean-counters

They hired a nice, ambitious woman as the first Head of the FBS. She had no idea what pressure she was about to face from above. Within twelve months, she was on stress leave. One of the FBS staff was made interim Head. She managed better with the stress, which was remarkable because she spent most of her time shielding us from ‘down the hill’ (Flinders is on a hill slope and the Admin wing is down the bottom of the hill).

Eventually, she moved on, largely because a new person was appointed as the Head of Faculty, who I could honestly say was the most despicable creature I’ve ever had the misfortune of dealing with. This person became the new interim Head. She now had the impossible task of being Head of both the Faculty and the FBS. To help her, she got approval to hire a heap of casual staff to do many of the mundane tasks for her. This, at a time when we were told to tighten our belts and when funding for conference travel was slashed.

She was a deadset bully – I called her that at a FBS staff meeting to everyone’s horror – and consequently I was in the firing line. I though her reply was interesting. If someone accuses you of being a bully and you disagree, you refute the allegation with an explanation. She simply said that she’d never been labelled a bully – she didn’t refute my allegation – which proved to be a lie.

After months of having to deal with the creature and having strange (deliberately disruptive) changes made to my role, I’d had enough. I’d gone to some very senior people in the university to complain (with all modesty, I’d been highly recognised by some of them during my time at Flinders) and the union. They were useless.

I quit before it all got the better of me, thinking I’d have little difficulty getting a position elsewhere. Now established as a heterodox economist, I had fat chance. I took up a few contract teaching roles over the next five years. The whole thing has cost me a fortune.

I’m, in a sense, retired. I generate enough of an income to live comfortably, but certainly not lavishly, and I am free to do what I want. In many ways I’m glad I have nothing to do with academia. Overall, I have no time for it, although its current state is largely the result of government policy rather than the nature of academics, although many Professors aren’t worth a Professor’s bootlace. Wasted brain power who play the game and exploit the system. Bill is one of the few academics I have high regard for.

Alan Dunn: Those students always existed. The system used to weed them out very quickly, to the benefit of everyone.

There is now a greater share of these students at university because the ‘qualifications’ required to obtain a reasonably well paid job have risen. These people are forced into the university system, at great cost to them, even though they just want a nice paid job. They have no interest in learning academically.

When I was young, kids at my high school with good Year 11 grades got jobs in the public service. There was no need to even matriculate, which was designed to prepare students for higher education.

And maybe the influx of foreign students adds massively to the revenue at the same time as giving the hierarchy an inflated idea of their importance?