The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

The IMF has outlived its usefulness – by about 50 years

The IMF and the World Bank are in Washington this week for their 6 monthly meetings and the IMF are already bullying policy makers around the world with their rhetoric that continues the scaremongering about inflation. The IMF boss has told central bankers to resist pressure to drop interest rates, even though it is clear the world economy (minus the US) is slowing quickly. It is a case of the IMF repeating the errors it has made in the past. There is a plethora of evidence that shows the IMF forecasts are systematically biased – which means they keep making the same mistakes – and those mistakes are traced to the underlying deficiencies of the mainstream macroeconomic framework that they deploy. For example, when estimating the impacts of fiscal austerity they always underestimate the negative output and unemployment effects, because that framework typically claims fiscal policy is ineffective and its impacts will be offset by shifts in private sector behaviour (so-called Ricardian effects). That structure reflects the ‘free market’ ideology of the organisation and the mainstream economic theory. The problem is if the theory fails to explain reality then it is likely that the predictions will be systematically biased and poor. The problem is that the forecasts lead to policy shifts (for example, the austerity imposed on Greece) which damage human well-being when they turn out to be wrong.

A recent UK Guardian article (April 13, 2024) – Are the octogenarian IMF and World Bank sprightly enough for the job? – questions whether the two multilateral institutions have outlived their usefulness.

The article concludes that:

… the governance structure of the two institutions still reflects the world of 80 years ago. The US chooses every World Bank president, while Europe gets to pick the IMF’s managing director. Banga will this week tell how he intends to make the bank a more ambitious and speedier organisation. A more fundamental question is whether the two institutions are actually fit for purpose.

Many people are unaware of the origins and the initial purpose of the IMF.

The IMF was initially conceived at the UN Monetary and Financial Conference at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944 as one of the two major international institutions (along with the World Bank) to rebuild the damaged economies after the Second World War and to ensure (in the case of the IMF) that there would be no return to the Great Depression.

The IMF was empowered to be an unconditional lender to nations in trouble, to ensure there would not be another collapse.

It quickly morphed into ensuring the fixed exchange rate system was sustained.

Its neoliberal credentials that drive its behaviour now, were not in evidence then.

It actively sought to maintain the market distortion that was imposed by the Bretton Woods system of currency convertibility.

All currencies were valued against the US dollar and the IMF loans subsidised these parities in the face of shifting trade balances.

In the beginning, the IMF was a Keynesian institution and sought to ensure the member nations could continue to build material prosperity.

When a nation was finding it hard to maintain its currency parity under the agreement – usually because it was running an external deficit and the supply of its currency to the foreign exchange markets was outstripping the demand as a consequence – the IMF would provide the nation with loans of foreign currency to allow its central bank to defend the currency while the nation adjusted.

While the IMF began imposing conditionality on its loans from its inception in 1944, the specific nature and extent of conditionality evolved over time.

In the early years, conditionality primarily focused on ensuring that borrowing countries pursued policies to maintain exchange rate stability and to address balance of payments problems.

But that changed in the late 1960s and beyond.

Then the conditionality expanded into a comprehensive assault on government provision and forced all sorts of neoliberal changes onto governments – outsourcing, privatisation, user pays, service cuts, etc.

This shift came as the Bretton Woods system was becoming unworkable, largely because it imposed massive social and political costs on nations that ran external deficits.

Those nations were forced to endure persistently high unemployment or lower than necessary economic growth as fiscal authorities had to impose austerity to reduce import demand and the central banks pushed up interest rates to attract capital inflow – all because the policy makers had to prevent the currency from breaching the agreed parities.

This led to a series of so-called competitive devaluations in the 1960s – which were realignments of a particular currency under the system – designed to improve the nations international trade competitiveness.

But as one nation gained IMF approval to realign, other nations then followed suit to maintain their own relative positions in international trade competitiveness – which defeated the purpose.

Further, as a result of the US running large external deficits, in part to ensure there were sufficient US dollars in the system – given its central role in the convertability system, and also because of its prosecution of the Vietnam War, nations started building up large US dollar reserves.

The fixed exchange rate system also attracted financial speculation against the currencies and the markets knew that they could bluff governments that had their arms tied by the system.

Some of those nations fearing that the US dollar would start to lose value then sought to convert their holdings into gold, which was a characteristic of the Bretton Woods system.

The US feared there would be a run on its gold reserves and on August 15, 1971, President Nixon announced the suspension of convertibility, which effectively ended the Bretton Woods system, even though there were attempts to restore it before they were finally abandoned by the – Jamaica Accords – in early January 1976.

Here is Nixon’s famous speech (from about 8:40 in the video he talks about proteting the US dollar):

Among other things, the Jamaica Accords modified the ‘articles of agreement’ which had defined the IMF from day one.

The collapse of the fixed exchange rate system meant that the IMF had no further role to play – as originally defined, given most nations chose to float their currencies, which freed domestic policy from having to manage currency parities.

But, with considerable deftness and in an increasingly neo-liberal milieu, the IMF reinvented itself and established its mission as being the lender to poor nations who faced currency pressures as a result of foreign debt accumulation.

This was at the same time as the economics profession was shifting from a Keynesian approach to the ideologically different Monetarism, which completely redefined the role of government and its juxtaposition with the private market place.

It was also at time when global financial capital was expanding and speculative shifts in finance across borders was becoming significant.

The IMF became a major force in asserting this neoliberal shift and the conditionality that they started to impose was a core component of this new mission.

The neo-liberal ideology came to the fore in the late 1970s when the IMF started to implement their so-called Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs).

These programs were a response to the debt crisis that engulfed the world – a crisis that was significantly related to IMF loans.

The debt crisis was constructed as a crisis for the developing nations but it was really a crisis for the first-world banks. The IMF made sure the poorest nations continued to transfer resources to the richest under these SAPs.

The SAPs were vehicles by which the IMF forced nations to adopt free market policies – the same sort of policy changes that created the conditions for the crisis in the advanced nations.

The poorest nations were forced to privatise state assets, make cuts to education and health services, cut wages, eliminate minimum wages and free up their banking sectors to allow speculative capital to prey on them.

The results in all cases was to increase the inequality in the wealth and income distributions, to increase poverty rates and open the nations to extensive environmental damage.

Nations with subsistence agriculture were forced to convert into cash for trade crops.

The impact of the increased supply on world markets was to reduce the price below the level that was necessary to repay the IMF loans.

More repressive conditions were then imposed.

Some nations pillaged their natural resources to the point that they had no export potential left but a residual of onerous IMF loans remained. And, in the process, they undermined the viability of their subsistence sector and so world hunger rose.

The obvious measure of the failure of this approach has been that the IMF has not decreased world poverty. In fact, the overwhelming evidence is that these programs increase poverty and hardship rather than the other way around. The IMF has a long-history of damaging the poorest nations.

There are many mechanisms through which the SAPs have increased poverty.

First, fiscal austerity is almost always targetted at cutting welfare services to the poor – which often means health and education (the IMF claims that educational and health cuts no longer happen).

But moreover, the cuts prevent sovereign governments from building public infrastructure and directly creating public employment.

Areas such as the military which do little to enhance quality of life are rarely included in the IMF cuts – in part, because these expenditures benefit the first-world arms exporters.

Second, public assets are typically privatised.

Foreign investors often benefit significantly by taking ownership of the valuable resources.

Third, contractionary monetary policy forces interest rates up which often discriminate against women who survive running small businesses.

But the restrictive monetary policies interact with the de-regulation of the financial sector such that the higher interest rates promote speculative investment (hot money) that fails to augment productive capacity.

Fourth, export-led growth strategies transform rural sectors which traditionally provided enough food for subsistence consumption.

Smaller land holdings are concentrated into larger cash crop plantations or farms aimed at penetrating foreign markets.

When international markets are over-supplied, the IMF then steps in with further loans.

But the original fabric of the land use is lost and food poverty increases.

Fifth, user pays regimes are typically imposed which increases costs of health care, education, power, and in some notable cases, reticulated clean water.

Many of the poorest cohorts are prevented from using resources once user pays is introduced.

Sixth, trade liberalisation involves reductions in tariffs and capital controls. Often the elimination of protection reduces employment levels in exporting industries.

Further, in some parts of the world child labour becomes exploited so as to remain “competitive”.

In 2013, I made the – The case to defund the Fund (June 6, 2013).

I also wrote this blog post –

The IMF – incompetent, biased and culpable (February 11, 2011) – which analysed the independent evaluation of the IMF, which concluded that the IMF was poorly managed, was full of like-minded ideologues and employed poorly conceived models.

When the Bretton Woods arrangements were scrapped in 1971, the IMF should have been scrapped then too.

That still holds.

It serves no useful purpose and has destroyed societies and communities as a result of its flawed applications and harsh adjustment programs.

While the IMF is now telling central banks they must maintain high interest rates and that fiscal authorities should be imposing austerity to maintain vigilance over inflation.

Last year, the IMF released a working paper – How We Missed the Inflation Surge: An Anatomy of Post-2020 Inflation Forecast Errors.

They also published an accompanying blog post (March 2023) – A remarkable demand recovery and changed dynamics in goods and labor markets contributed to misjudgments.

The working paper admits to major forecasting errors by the IMF, and, more importantly, they acknowledged that there was systematic bias in those forecast errors.

This is a point I have made before – all forecasts turn out to be inaccurate because of the nature of the exercise – trying to predict an intrinsically uncertain future.

One should not judge the veracity of the underlying ‘model’ – formal or otherwise – that generated the forecasts just because there are forecast errors.

Large errors are clearly of concern because they can lead to actions (policy etc) that impact on human well-being.

But of greater concern are forecasting errors that are systematically biased.

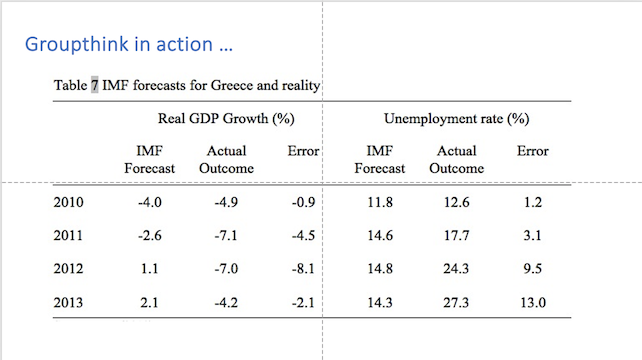

For example during the GFC, the IMF forecasts between 2010 and 2013 for Greece were so biased.

Here is a graphic I produced for some presentations at the time.

The bias is evident – the IMF was advocating harsh austerity at the time that was imposed on Greece by the European Commission.

Its modelling produced estimates of the impacts that were relatively small (in negative terms) despite people like me arguing that the results would be disastrous.

As the years unfolded the serial errors became larger – because the underlying forecasting model was not capable of reflecting real world processes.

The situation, of course, became even worse after 2013, which led to the IMF admitting their underlying modelling was grossly incorrect.

I wrote about that in this blog post – We are sorry (February 14, 2010).

The recent IMF working paper concluded that:

We find that headline forecasts saw significant downward bias in the focal period 2021Q1-2022Q3, at about 1.8 percentage points (pp) … We also find evidence of oversmoothing in the forecasts, and a positive and significant correlation between cross-country estimates of the magnitude of the smoothing coefficients and the headline inflation forecast errors.

In other words, they continually under predicted the resulting inflation, in part because they overestimated the output effect of the pandemic.

There output predictions during the early pandemic years were understated because their models consider spending multipliers are low, which leads to the conclusion that fiscal stimuli will have small effects.

This is the flip-side of their Greek errors where they claimed austerity would have small negative effects.

They try to explain these systematically biased errors by appeal to:

a stronger-than-anticipated demand recovery; demand-induced pressures on supply chains; the demand shift from services to goods at the onset

of the pandemics; and labor market tightness.

They clearly didn’t understand fully the implications of providing fiscal support to maintain incomes to households, at a time when goods suppliers were incapable of meeting extra demand, which was forthcoming because the lockdown restrictions stifled service sector spending.

The resulting imbalance drove the inflationary pressures and once the restrictions were relaxed and transport and factories returned to more normal previous levels of activity, the supply side constraints abated and the inflationary pressures started to recede.

Central banks, bar the Bank of Japan, mistook the inflationary pressures as a manifestation of general excess demand, which required higher interest rates.

The IMF supported that approach because they share the same defective New Keynesian macroeconomic framework.

Conclusion

So the reason the IMF underestimated the inflationary potential of the pandemic and now overstates the inflation threat is because the underlying mainstream macroeconomic model that they use is defective.

We keep getting ratification of that as the IMF deals with major global crises.

Each time they make major, systematically-biased errors in their analysis.

I remind readers that on February 11, 2011, the IMF’s independent evaluation unit – Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) – released a report – IMF Performance in the Run-Up to the Financial and Economic Crisis: IMF Surveillance in 2004-07 – which presented a scathing attack on the Washington-based institution.

It concluded that the Fund was poorly managed, was full of like-minded ideologues and employed poorly conceived models.

I wrote about that in this blog post (among others) – IMF groupthink and sociopaths (April 6, 2016).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The talk about inflation is solely on the purpose to justify interest rates hikes and, in the process, garnish zombie banks’ coffers with the money they are unable to earn on their own.

As western economies get more and more monopolized (by multinacional corporations), inflation is a whim away from the CEO of the large hedge fund – if shareholders are not very happy about their earnings.

But there’s a price to pay.

Sometimes, when someone repeats something time and time again, it eventually ends up happening. A self-fulfiling profecy, maybe?

Zombie banks dwell in zombie economies and zombie economies don’t grow at 5%, which is what the elites expect to yield on their funds.

Zombie economies need more and more subsidies to keep big corporations afloat (nobody cares for small corporations, though) and so, central banks keep “printing” (or adding zeros on a computer screen if you prefer it that way).

Pam Martens and Russ Martens from “Wall Street on Parade” posted a piece last week about the largest central bank of the world, the US Fed (https://wallstreetonparade.com/2024/04/the-black-swan-rears-its-head-the-fed-has-negative-capital-using-gaap-accounting/), where she wrote that

“(…) as of December 27, 2023, using GAAP accounting, the Fed had negative capital of $82 billion while the New York Fed represented $69.6 billion of that negative capital, or 85 percent”.

Could we say that it is technically insolvent?

Of course it won’t fail, as it keeps “printing”, but tell me this: what’s the diference between the US right now and the Weimar Republic?

IMF: also known as the Infant Mortality Fund, based on what it causes.