With a national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot…

Education should be a nation-building investment not a tax on graduates

Today, I am Perth giving a keynote presentation to the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) 2023 Congress. My talk is titled – Why fiscal fictions lead to inferior health policy outcomes. Given the travel time to the other side of the world (the continent at least) – us East Coasters get restless when we have to come here – and my commitments at the Congress, I haven’t time to produce a post. So today, thanks to our regular guest blogger Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period of time, we have a discussion about fiscal fictions and higher education policy, which is a very nice dovetail to the theme of today. Today he is specifically going to talk about the current concerns about student debt in Australia. Over to Scott …

Background

When I completed my university degree (with excellent teaching by a certain Professor Bill Mitchell) it was largely free.

The free university education I received came to a screaming halt with the introduction of a Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) by the Hawke Labor government in 1989.

The introduction of the scheme was part of a more widespread restructuring of the university sector in the wake of the – Report of the Committee on Higher Education Funding – aka the Wran Report (April 1988).

At the time:

The Committee on Higher Education Funding was asked to develop options for supplementing the funding of the Australian higher education system which could involve contributions from students, their parents, and employers.

The basic idea of the original program was that students were charged a fee of $1,800 per year with the balance of the cost being met by the federal government.

Students could pay their contribution (HECS) upfront or defer payment in which case they accumulated a HECS debt.

When a student accumulated a HECS debt they would repay the debt via the taxation system once their income reached a predetermined threshold.

The loans are interest-free.

However, the amount of debt is increased each year according to the Consumer Price Index.

The amount a student repays varies according to the level of income they receive and varies from 1 per cent of their income up to 10 per cent of their income.

The scheme has continued to the current day with various amendments and changes to the level of fees charged and the earning thresholds at which the debt is paid back.

In the most recent iterations of the program (now called the HELP program-HELP standing for the Higher Education Loan Program) governments have attempted to use the scheme as a price mechanism to lure students into certain degrees and areas of study.

The extreme of this approach was the former coalition government’s – Job Ready Graduates Package that aimed to:

incentivise students to make more job-relevant choices, that lead to more job-ready graduates, by reducing the student contribution in areas of expected employment growth and demand.

They did this by radically shaking up the payment tiers:

For example, a student studying humanities or social science courses in 2020 was liable for a student contribution of $6,684 pa, whereas someone commencing the same courses in 2021 has a student contribution of $14,500 pa. On the other hand, someone studying agriculture or mathematics had a contribution of $9,527 pa in 2020, which is reduced to $3,950 pa in 2021. Continuing students will pay the lesser of the amount their course is liable for in 2021 and the indexed 2020 levels. Thus, for example, a student continuing in communications qualification can only be charged $6,804 pa in 2021, while a new student in the same course could pay $14,500 pa.

A tax on graduates

There are most likely a lot of people who think that graduates should pay their way.

There would be the usual arguments about “taxpayers’ money” and “responsible spending” etc.

But the HECS/HELP repayments are an extra tax on graduates.

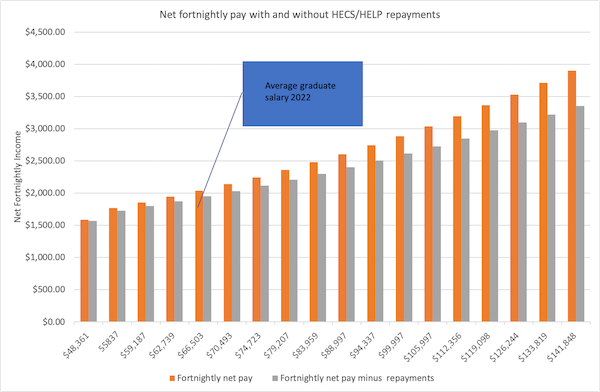

Once a graduate earns $48,361 (around $6000 more than the minimum wage) they start paying an additional one per cent of their income.

At the average graduate salary of around $68,000 they pay 3.5 per cent and once their income reaches $141,848 they pay an extra 10 per cent.

As the graph below illustrates, at lower levels of gross income the difference between take-home pay with and without a HECS/HELP debt is in the region of around $30 per fortnight, it ramps up to around $100 difference at the average graduate income and around $350 at the extreme end.

So we have the situation whereby graduates, who often have already forgone significant levels of income during the years spent studying are screwed a bit further by what is essentially an extra tax for their troubles.

But it doesn’t stop there.

Because the debt is indexed annually in line with the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the time it takes graduates to clear even a modest debt tends to blow out.

Let us assume that I have just completed my Bachelor of Economics (let’s hope the course is framed using a solid MMT lens).

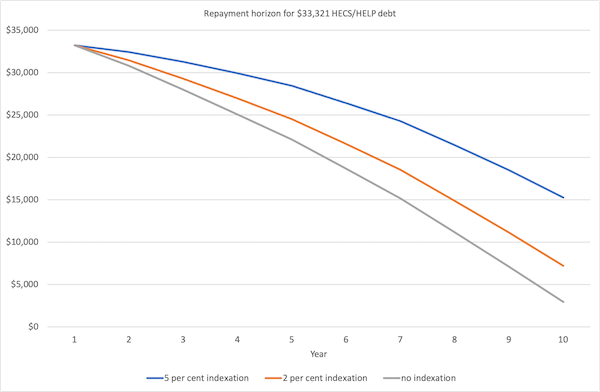

Given current fee structures my 3-year degree would have attracted a debt of $33,321.

Let’s also assume that I start earning the average salary for an economics graduate of $68,000 and that I am lucky enough to get an annual pay increase of 2 per cent.

The graph below illustrates the impacts of different indexation scenarios on my repayments.

At 5 per cent indexation, I would be left with a debt of around $15,000 after 10 years of constant minimum repayments.

At 2 per cent indexation, the same starting debt would be reduced to around $7,000 after 10 years.

If there was no annual indexation, my 10-year balance would be around $3,000.

These are fairly conservative scenarios.

There are lots of stories floating around at the moment about graduates facing significant levels of debt years after they have finished university because either their level of income has not been significantly high to put a dent in their balance and/or because annual indexation has simply wiped away any payments made.

For example:

1. How HECS and HELP debts have helped entrench women’s economic disadvantage (March 4, 2023).

2. Growing calls for student HECS-HELP loan indexation to be abolished as inflation sends debts soaring (April 3, 2023).

Such is the reward for obtaining a tertiary education!

A Call to Action

Given these types of outcomes, there have recently been calls for action on student debt targeting the level at which repayments kick in and also the indexation of debt.

Unfortunately, there has been no talk about wiping student debt and making tertiary education free.

In federal parliament, the Australian Greens party have been leading the charge as this UK Guardian report (January 28, 2023) – Inflation-driven higher education debt increases to hit millions of Australians – illustrates.

We read that:

Abolishing indexation on student debt and raising the minimum repayment threshold would be a good start, and provide much needed money in people’s pockets at a time when they are struggling to make ends meet or pay rent.

This ukg report (May 8, 2023) – MPs push to ease student debt burdens as record Help loan indexation looms – demonstrates that other politicians, including the newly elected independent MP Zoe Daniels argue that the scheme:

After being set up in the 1980s, Help is no longer fit for purpose and is overdue for independent review.

I agree! It was poorly conceived at the time and has become more problematic as time has passed.

Predictably, the suggestion that changes should be made to the system was met with a brick wall.

There were all the usual reasons – the government can’t afford it, it is unfair to taxpayers etc.

The argument that changing the threshold or freezing indexation will cost taxpayers is a complete furphy.

A furphy is a rumour or story, especially one that is untrue or absurd), perpetuated by those who do not understand the way government spending operates.

Sadly, this includes one of the architects of the original HECS program, Bruce Chapman (an economist) who frankly should know better, but I guess you can’t teach an old dog new tricks.

In an ABC news article (April 19 2023) on the government’s refusal to budge on HECS/HELP debt – Freezing HECS-HELP indexation won’t put more money in your pocket in the short term – Chapman was quoted as saying:

… having graduates pay indexation on their degree was still the fairest way to support university students.

Further:

In the absence of indexation, all taxpayers are paying for the opportunity cost of the debt.

To apparently help clarify his position he presented an example of a graduate with a $10,000 debt (pretty unrealistic given current rates).

He opined:

It might have taken that graduate a number of years to earn enough to start repaying the debt. And it might ultimately take them, say, 13 years to pay the debt back … By this time, that $10,000 might only be worth $8,000 in today’s money thanks to price inflation.

True, a dollar today is worth less tomorrow, but what is the problem?

He goes on to suggest that:

If the graduate pays back the $10,000 without any indexation, there is a gap of $2,000 that the government ultimately misses out on.

… If you just get the $10,000 back and no more, the government is subsidising that by a very large extent because price inflation is taking away the value of the $10,000.

Then he asks the big question:

Where’s the other $2,000 coming from? It’s coming from taxpayers.

Oh dear, what can I say?

Education as nation building

Governments of all persuasions are fond of talking up nation-building investment.

At times they seem obsessed with it.

This makes you wonder why they don’t treat education as an important investment in nation-building.

There is no end of research and reports that point to the national benefit achieved via a strong tertiary education sector (and all education for that matter).

Even in the original Wran report we read

The Committee agrees with the general arguments that it is in the interests of all Australians to have a better educated population for a variety of social, cultural and economic reasons. A better educated population strengthens our culture and promotes a fuller understanding of ourselves as a community. Australia’s future economic prosperity depends, in part, on access to a more flexible and responsive labour force, high quality research and development, and technological innovation, in all of which higher education has an important role to play.

If this was the view of the Committee, then why on earth did we go down the path of burdening graduates with an extra tax and debt that would take years to extinguish?

It was clear that while the importance of higher education was understood, the government’s emerging neo-liberal agenda meant that tertiary education was recast as a private good to be paid for by students.

The Wran report states:

Society in general benefits from higher education, but considerable private benefits accrue to those who have the opportunity to participate … While more and better higher education is an important national need, its achievement would involve a substantial drain on Government outlays if funded by the Commonwealth alone.

It would be fair to say that the development of the scheme was poorly informed by the facts.

Firstly, while it is true that individuals benefit from their tertiary education, the actual division between private and public benefits of tertiary education was never spelt out in the report.

Some research suggests that the public benefits outweigh the private benefits, but it is fair to say that the actual division is difficult to measure precisely.

See for example – Estimating the public and private benefits of higher education.

The papers do make a solid case for identifying the suite of public benefits that accrue from tertiary education.

Secondly, the idea that expanding the provision of services in the tertiary education sector would be a drain on government outlays is, as we know, patiently incorrect. A sovereign currency-issuing government faces no constraints on its ‘outlays’.

Time for a rethink

So how do we fix all of this?

If we accept that education and the development of skills and knowledge is an important nation-building investment, then the answer should be clear.

The government should immediately wipe all existing student debt and make higher education free to anyone who wishes to undertake it.

Added to this tertiary education institutions should be properly funded and dismantled from the current market-led approaches that have destabilised high education over the past few decades.

History has shown free tertiary education leads to desirable outcomes for individuals and results in positive wide-ranging benefits to the country as a whole.

The government just needs to get on and do what is right.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Theodore Schultz

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Schultz

Schultz researched into why post-World War II Germany and Japan recovered, at almost miraculous speeds from the widespread devastation. Contrast this with the United Kingdom which was still rationing food long after the war. His conclusion was that the speed of recovery was due to a healthy and highly educated population; education makes people productive and good healthcare keeps the education investment around and able to produce. One of his main contributions was later called Human Capital Theory, and inspired a lot of work in international development in the 1980s, motivating investments in vocational and technical education by Bretton Woods system International Financial Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

I’ve never understood the macro arguments for ‘student debt’.

In reality there is no debt. It’s just a list of people who pay a higher taxation rate than anybody else, that may, or may not, be time limited.

Except those people are in short supply – otherwise they would not be able to command a wage higher than the living wage. Therefore if you increase their costs as a group, they will simply pass that cost on as a group in the form of higher wage demands.

The costs are therefore paid in any case by those who haven’t been to university, as they are far less likely to be able to pass on increased costs as wage demands.

Where is the empirical evidence that wages for those with degrees are suppressed by some economic force such that the tax incidence stays with the graduate?

In reality, all you have out of the policy is the economic dead loss costs of running a pointless ‘student loan system’. Yes it’s a job creation scheme, but surely we can find a better use for people.

When Kelton’s ‘The Deficit Myth’ was first released (prior to the pandemic), one of that book’s most substantive criticisms (I read), related to the “absence of a fully developed theory on inflation management”.

Indeed, while I was recently seeking support from a Greens politician to promote MMT in Parliament, she said: “now is not the time, because we have high inflation”.

Meanwhile Chalmers says “the public won’t accept taxes to control inflation” (and indeed it won’t work in a fair manner because rich people will continue consuming regardless of taxes), which leaves us with an ‘independent’ central bank to manage inflation by lifting interest rates.

Neoclassical economists despise “mission based” systems like MMT because the freemarket ‘invisible hand’ demands non-interference by government.

I think MMTers have to ‘bite the bullet’ re inflation; eg the pandemic definitely required price controls, rationing, and subsidization of essentials for locked- down workers, for fair acess to essentials by all, even before the war in Ukraine caused more supply breakdowns contributing to the current bout of inflation.

And of course mainstream economists are pointing to the massive “money printing” by governments to support the economy during the pandemic (which they called “MMT”), as evidence “MMT” causes inflation…..

But government should only have supported locked down workers to buy the essentials, rather than throwing money at people and busineses who didn’t need it.

So there’s the problem; if we want “an economy that works for all’, by granting the currency-issuing government the power to issue ‘debt free’ money for public purposes, while controlling inflation, we will have to embrace a partially planned economy which matches available resources to desired social outcomes, and in which the public sector is freed from the necessity to tax or borrow from the (naturally reluctant, greedy) private sector.

As noted above, even progressive (Greens) politicians aren’t interested in MMT, in the absence of clear policies re inflation control capable of dealing with all circumstances, acceptable to the public.

Hi Scott,

I agree that university education should be free, but to overcome the issue of the subsidy to those who can expect high incomes after graduating in law, medicine etc, I would make the income tax system more progressive.

In addition, I would have more rigorous entry standards, but maintain the different pathways to getting into University, e.g. mature-age students. From my experience, there are too many students attending universities. The related issue to entry standards is the quality of courses, which is a minefield, given the ideological biases of some of my former colleagues in Economics!

Unfortunately, education became another market for the 1% to binge on.

Financial capitalism is like a colossal ponzi scheme, that only works as long as more and more people get in the debt trap.

We all understand that high school degrees are not enough basic learning anymore.

Which amounts to say that a country can get behind other competitors, if the educational system lags behind.

And the west is lagging behind the east.

East that already learned how to avoid the debt trap.

@Neil Halliday,

You state that Kelton’s ‘The Deficit Myth’ was criticized for the “absence of a fully developed theory on inflation management”. Can you supply a reference for that?

I ask because I don’t know anyone who has a ‘fully developed’ theory on inflation management — particularly one that has actually been implemented in policy and stood the test of time. Central bank control over the size of the money supply? The U.S. abandoned it by the mid-1980s. Phillips-curve-inspired interest-rate policy? It’s certainly capable of producing stagnation, but it’s useless dealing with supply-side inflation.

You call for “clear policies re inflation control capable of dealing with *all* circumstances, acceptable to the public” (emphasis added). Could you tell us where we can find policies that are universal in their application and public acceptance?

Dear Martin, I don’t see the reason to tax earned incomes at all. I’m going to write a paper: Tax in the Era of Fiat Money. I have a lot to say.

@Carol Wilcox

exactly , Martin has apparently forgotten the currency-issuing government should not be taxing or borrowing from the private sector, to fund education.

But politicians, following academic economic groupthink, shout “inflation” – so the MMT narrative is dead in the water.

@James E Keenan,

The criticism was in the ‘comments’ section of a major book retailer 3 years ago, so I won’t be able to retrieve it now.

But my point stands; politicians always highlight the inflation problem, so obviously Kelton failed to convince the mainstream, though many other people regarded her book (a NYT best-seller at the time) as “epoch changing”….which most of us here hoped it would be. Instead, 3 years later even the ABC refuses to look at MMT re showing the way to a better economy which works for all.

To cut a long story short: one sympathetic ANU economist described MMT as “communism”, and I can see where he is coming from; obviously if you want to manage inflation without using economy-killing monetary policies, you have to (literally) control prices, and also ration access to (supply constrained ) resources, while guaranteeing everyone access to the essentials, via above poverty employment for all (aka the Job Guarantee).

As to your final question: the answer is no – which means MMTers are doomed to continue whistling in the wind, so long as “communism” is a dirty word in our “freedom values” Western ideology which regards planned ‘common prosperity’ as incompatible with freedoms and choices of individuals seeking to maximize their own wealth in a free “invisible hand” market economy.

“obviously if you want to manage inflation without using economy-killing monetary policies, you have to (literally) control prices, and also ration access to (supply constrained ) resources”

You don’t.

The Job Guarantee does it all automatically. It is the stabilisation policy under MMT and it works in all circumstances – replacing interest rate adjustments which are then returned to zero. In effect we move the stabilisation policy from the market for money to the market for labour.

Beyond that MMT is essentially tax and spend. If you want more government, you have to tax to release the resources for that more government. That’s because government can only really hire that which the private sector hasn’t the current ability to use.

MMT is about as far away from communism as possible. The stabilisation system comes from three entirely automatic stabilisers: the Job Guarantee, counter-cyclical tax response, and a free floating exchange rate.

In other words, unlike at present, there would be no men in ivory towers making stabilisation decisions. It’s entirely autonomous.

If the population won’t pay the tax, then they can’t have the government – and you reduce discretionary spending. Coats have to be cut to cloth.

We may have a magic money tree, but we don’t have a magic porridge pot.

Is it possible for taxation to remedy some types of inflation (apart from LVT, of course)? The ‘wage/price spiral’, for instance, surely can only be controlled by a prices and incomes policy like we had here in the 70s – I think this is what Bill says.

@Neil Wilson:

“The Job Guarantee does it all automatically. It is the stabilisation policy under MMT and it works in all circumstances – replacing interest rate adjustments which are then returned to zero. In effect we move the stabilisation policy from the market for money to the market for labour.”

Thanks for this. But I think you will find neo-classical free market ideologues regard the Job Guarantee itself as “communism”. Certainly, even ALP members have told me the JG is impossible, presumably because JG jobs are not ‘real jobs’ as defined by free market ideologues.

Eg Noah Smith thinks only ‘real jobs’ are ‘productive’ jobs – he is obviously thinking in terms of ‘value’ determined in profit-driven markets.

Anyway, your point about the JG being an automatic price stabilizer is important; maybe I can point that out to the Greens Senator who doesn’t want to promote MMT at present “because we have high inflation”…

Ideologues don’t think in terms of jobs. They think in terms of business services. Nobody has a job in neoliberal land. You’re a service provider on a gig.

In the real world workers sell labour hours for money. Whether those labour hours are productive is down to those who purchase those hours and use them. That’s the only reason capitalists are worth paying – the productive transformation of labour hours into labour services.

In a world of endogenous money like ours, if the individual transforms labour hours into labour services themselves, why would we need to pay out for a profit share? At that point it would add no value.

If anybody thinks JG jobs are not productive, the solution lies in their capitalist hands – hire the people and use them for something else. The JG won’t bid back.

Capitalists can always get rid of JG jobs. By being a capitalist rather than a rentier.

@ Larry Kazdan re: ‘Germany and Japan recovered, at almost miraculous speeds from the widespread devastation. Contrast this with the United Kingdom which was still rationing food long after the war.’ A lot of words are probably needed to examine the post-war comparative success of West Germany and Japan. I think though, you’re probably overplaying the speed post-war of recovery and nutrition difference. Food rationing in W. Germany, as the UK, lasted until 1954, and I think Japan about the same. Not just due to the war but also disastrous winters and harvests post-war. The Japanese/American Govt was still buying up the rice harvest until 1954. The US divided up shipments of its surplus wheat to Japan and Korea depending on surges in communist threat.

@Halliday

“I’d far rather be happy than right” – Slartibartfast

The idea that we live in a free market does not stand up to any sort of statistical analysis. There are no normal distributions in sight in the economy.

We live in a centrally planned economy where corporations do the central planning.

Interest rate management (apart from being an obvious example of central planning by the corporate sector) clearly is not a respectable control mechanism for inflation. A control mechanism that takes years of wanton destruction to achieve the desired effect? Is there any empirical evidence for it having any useful effect?

@ Neil Wilson.

“Capitalists can always get rid of JG jobs. By being a capitalist rather than a rentier.”

Yes, but I am talking with a politician-economist who thinks “now is not the time to preach MMT because we have high inflation”.

My reply to her is government should seek – with the approval of the electorate – a prior claim on a proportion of the nation’s available resources, as necessary, eg, to build sufficient public housing, in order to avoid taxing to “create fiscal space for govt.” (to avoid inflation).

Taxing to create fiscal space sounds too much like taxing to fund govt. spending, whereas my proposal above by-passes that particular stumbling block, given that taxes in general are politically toxic in mainstream politics.

From ‘The Conversation (in Australia): “While Labor MPs would be unlikely to say so publicly, it is likely many regard the Greens as a “destabilising influence” on their end of the spectrum, if only because Greens MPs can propose spending, uninhibited by the likelihood of having to balance an entire budget themselves” (with increased taxes, or lower govt. spending).

Treasury issuing ‘debt free’ money to the rescue?

@Neil Halliday: the scarce resource required ‘to build sufficient social housing’ is land, and the means for government to acquire that is Land Value Tax. If they don’t use LVT they either pay the landowner the current price (capitalised rent) or, as NeilW suggests, compulsorily purchase (at what price?) or ‘make them an offer they can’t refuse’.