In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Australia – inflation rises but with no wage pressures evident there is no case for interest rate rises

The Tweets have started already demanding an interest rate rise in May at the next RBA Board meeting. Bankers, media commentators who just are conduits for the bankers – all with vested interests. Today’s data release from the Australian Bureau of Statistics – Consumer Price Index, Australia (April 27, 2022) – has fuelled their mania. Inflation in the March-quarter 2022 rose to 2.1 per cent (5.1 per cent for the 12 months) on the back of rising automotive fuel costs (uncompetitive cartel and deliberate government petrol tax policies), global supply chain disruptions (pandemic) and material shortages (supply chain and bushfires). As long as these influences are present, inflation will remain at elevated levels. But with wage pressures absent, it is hard to make a case that the rising inflation is now entrenched. Certainly, the long-term expectations measures would not suggest that. I cannot see why the RBA will hike rates in May. More evidence of wage pressures would be needed one suspects.

The summary Consumer Price Index results for the March-quarter 2022 are as follows:

- The All Groups CPI rose by 2.1 per cent for the quarter.

- The All Groups CPI rose by 5.1 per cent over the 12 months.

- The major determinants were Automotive fuel (up 11 per cent) and New dwelling purchase by owner-occupiers (up 5.7 per cent).

- The Trimmed mean series rose by 1.4 per cent (up from 1 per cent) and by 3.7 per cent over the previous year (up from 2.6 per cent).

- The Weighted median series rose by 1 per cent (up from 0.9 per cent) and by 2.6 per cent over the previous year (up from 2.6 per cent).

The ABS Media Release notes that:

Continued shortages of building supplies and labour, heightened freight costs and ongoing strong demand contributed to price rises for newly built dwellings. Fewer grant payments made this quarter from the Federal Government’s HomeBuilder program and similar state-based housing construction programs also contributed to the rise …

The CPI’s automotive fuel series reached a record level for the third consecutive quarter, with fuel price rises seen across all three months of the March quarter.

The rise in tertiary education reflected the continuing impact of updated student contribution bands and fees, introduced last year.

Short assessment: The inflation is being driven by a relatively narrow set of circumstances related to the supply disruptions from the global pandemic and shortages of timber due to the massive bushfires in late 2019/early 2020 which burned down lots of forests and created a shortage in timber.

The OPEC cartel is pushing oil prices up.

And significantly, cost pressures from explicit government decisions (fewer grants, user pays in higher education, etc) have pushed prices up.

It is hard to see this as an entrenched episode independent of the pandemic supply issues and possibly the Ukraine War.

It is also hard to see how interest rate rises will reduce these pressures (see below).

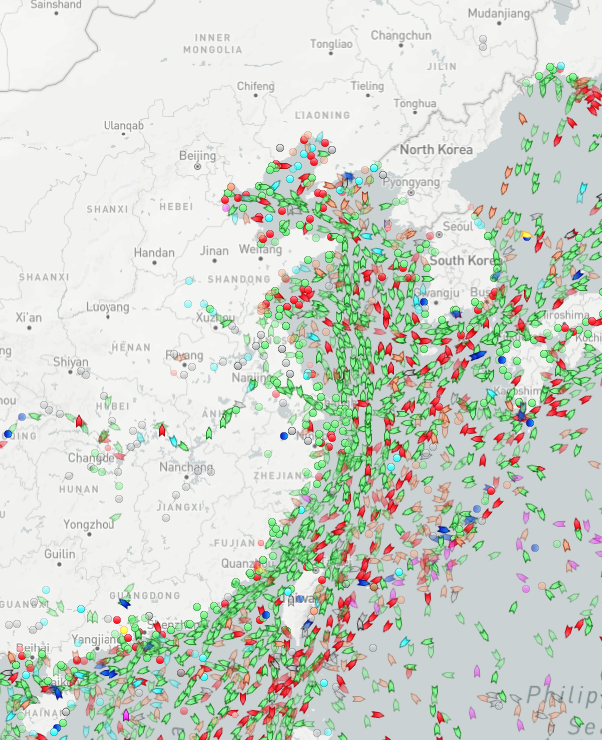

Update: Here is a graphic image of the ships queuing outside the largest port in the world – Shanghai – as a result of the Covid lockdown there. This is a supply constraint and nothing to do with fiscal deficits, central bank bond purchases etc (thanks to Marine Traffic). The red dots are tankers and the green dots are cargo vessels.

Trends in inflation

The headline inflation rate increased by 2.1 per cent in the March-quarter 2022 and 5.1 per cent over the 12 months, up from the annual rate of 3.7 per cent recorded last quarter. But the rise is transitory (mostly an adjustment in fuel prices as transport resumes and building materials).

Many commentators are claiming there is an upward trend in inflation but once we take out these transitory factors, the trend at best is modest.

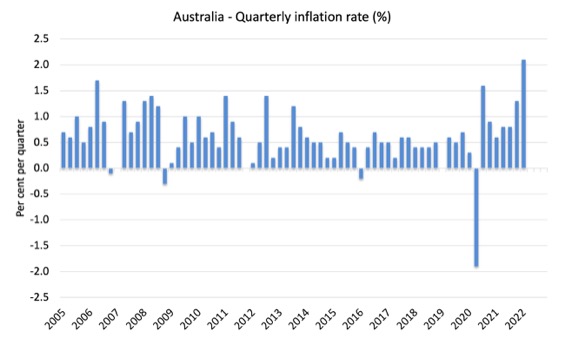

The following graph shows the quarterly inflation rate since the March-quarter 2005.

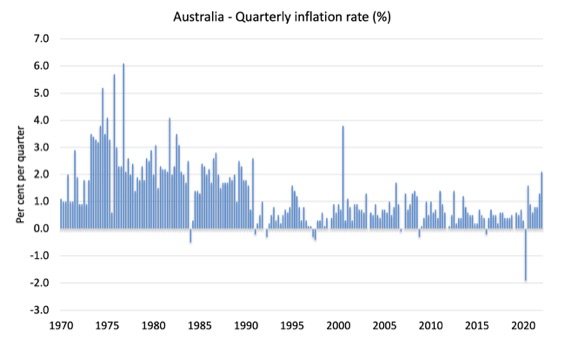

To put that into historical perspective, here is the series since the March-quarter 1970. We are nowhere near the inflationary pressures that followed the OPEC price rises in 1973.

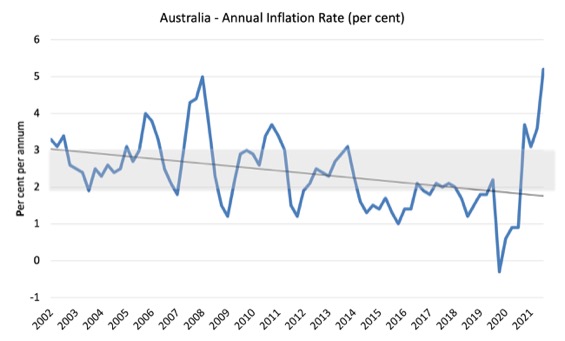

The next graph shows the annual headline inflation rate since the first-quarter 2002. The black line is a simple regression trend line depicting the general tendency. The shaded area is the RBA’s so-called targetting range (but read below for an interpretation).

The trend inflation rate over this long period is downwards.

What is driving inflation in Australia?

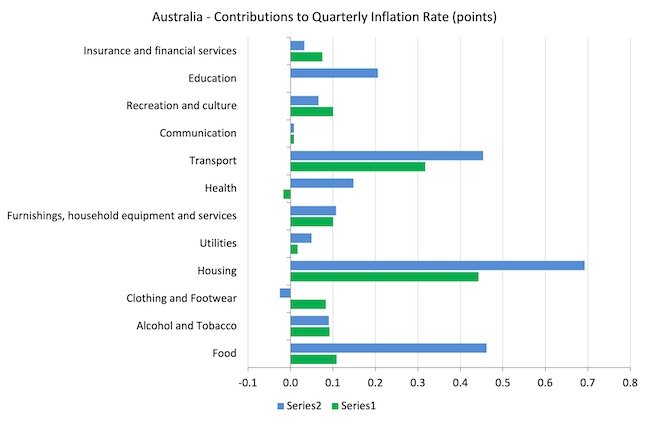

The following bar chart compares the contributions to the quarterly change in the CPI for the March-quarter 2022 (blue bars) compared to the December-quarter 2021 (green bars).

Note that Utilities is a sub-group of Housing.

This quarter it is petrol, housing and food driving the inflation.

None of these influences have much to do with the state of the economy – oil prices are cartel driven and the housing rises are due to shortages of inputs arising from supply disruptions and bushfires.

The ABS notes that food price rises – “reflecting high transport, fertiliser, packaging and ingredient costs, as well as COVID-related disruptions and herd restocking due to favourable weather.”

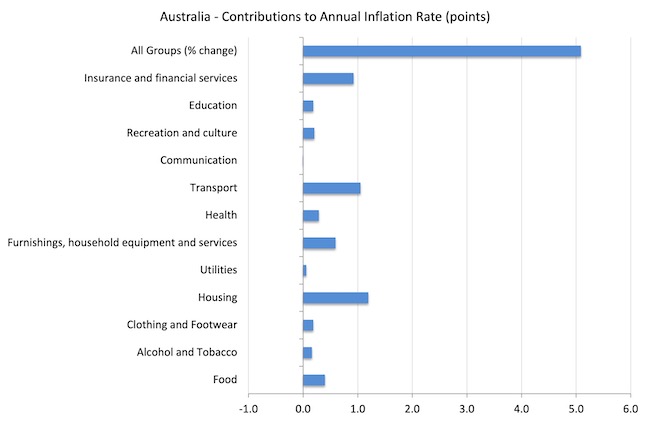

The next graph provides shows the contributions in points to the annual inflation rate by the various components.

Inflation and Expected Inflation

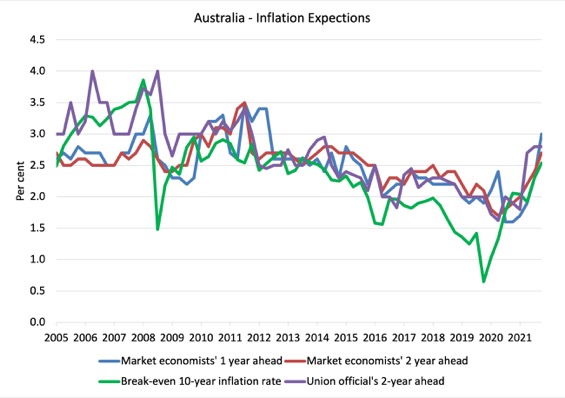

The following graph shows four measures of expected inflation expectations produced by the RBA – Inflation Expectations – G3 – from the March-quarter 2005 to the March-quarter 2021.

The four measures are:

1. Market economists’ inflation expectations – 1-year ahead.

2. Market economists’ inflation expectations – 2-year ahead – so what they think inflation will be in 2 years time.

3. Break-even 10-year inflation rate – The average annual inflation rate implied by the difference between 10-year nominal bond yield and 10-year inflation indexed bond yield. This is a measure of the market sentiment to inflation risk.

4. Union officials’ inflation expectations – 2-year ahead.

Notwithstanding the systematic errors in the forecasts, the price expectations (as measured by these series) have risen over the last year, which is hardly surprising.

But they are hardly going ‘through the roof’.

The most reliable measure – the Break-even 10-year inflation rate – rose from 2.3 per cent (below the lower bound of the RBA targetting range) to 2.5 per cent (within the range).

This measure is a good indicator of long-term inflation expectations.

That supports the notion that this is not yet an endemic inflationary episode.

Implications for monetary policy

What does this all mean for monetary policy?

There is some modest rise in expected inflation but the most reliable long-term indicator is well within the RBA range.

The private banking economists that are continually wheeled out in the media to comment on prospective interest obviously talk up interest rate rises because their organisations benefit, which poses the question as to why they are used in this way and held out as independent authorities.

But, in my view (with no vested interests), the inflation trends provide no basis for any expectation that the RBA will hike interest rates in the coming month.

The RBA has consistently said they will not increase rates until wage pressures are pushing inflation up.

Wage pressures are not evident as yet (next data on May 18, 2022).

There are some obvious and predictable increases in cost pressures due to the economy trying to deal with the pandemic, which is being exacerbated by anti-competitive behaviour in world oil markets.

Some government policy changes have pushed the March-quarter inflation rate up.

None of that represents any major structural bias towards persistently higher inflation rates.

The RBA uses a range of measures to ascertain whether they believe there are persistent inflation threats.

Please read my blog post – Australian inflation trending down – lower oil prices and subdued economy – for a detailed discussion about the use of the headline rate of inflation and other analytical inflation measures.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is designed to reflect a broad basket of goods and services (the ‘regimen’) which are representative of the cost of living. You can learn more about the CPI regimen HERE.

The RBA’s formal inflation targeting rule aims to keep annual inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index) between 2 and 3 per cent over the medium term.

The RBA also does not rely on the ‘headline’ inflation rate. Instead, they use two measures of underlying inflation which attempt to net out the most volatile price movements.

To understand the difference between the headline rate and other non-volatile measures of inflation, you might like to read the March 2010 RBA Bulletin which contains an interesting article – Measures of Underlying Inflation. That article explains the different inflation measures the RBA considers and the logic behind them.

The concept of underlying inflation is an attempt to separate the trend (“the persistent component of inflation) from the short-term fluctuations in prices. The main source of short-term ‘noise’ comes from “fluctuations in commodity markets and agricultural conditions, policy changes, or seasonal or infrequent price resetting”.

The RBA uses several different measures of underlying inflation which are generally categorised as ‘exclusion-based measures’ and ‘trimmed-mean measures’.

So, you can exclude “a particular set of volatile items – namely fruit, vegetables and automotive fuel” to get a better picture of the “persistent inflation pressures in the economy”. The main weaknesses with this method is that there can be “large temporary movements in components of the CPI that are not excluded” and volatile components can still be trending up (as in energy prices) or down.

The alternative trimmed-mean measures are popular among central bankers.

The authors say:

The trimmed-mean rate of inflation is defined as the average rate of inflation after “trimming” away a certain percentage of the distribution of price changes at both ends of that distribution. These measures are calculated by ordering the seasonally adjusted price changes for all CPI components in any period from lowest to highest, trimming away those that lie at the two outer edges of the distribution of price changes for that period, and then calculating an average inflation rate from the remaining set of price changes.

So you get some measure of central tendency not by exclusion but by giving lower weighting to volatile elements. Two trimmed measures are used by the RBA: (a) “the 15 per cent trimmed mean (which trims away the 15 per cent of items with both the smallest and largest price changes)”; and (b) “the weighted median (which is the price change at the 50th percentile by weight of the distribution of price changes)”.

Please read my blog post – Australian inflation trending down – lower oil prices and subdued economy (January 29, 2015) – for a more detailed discussion.

So what has been happening with these different measures?

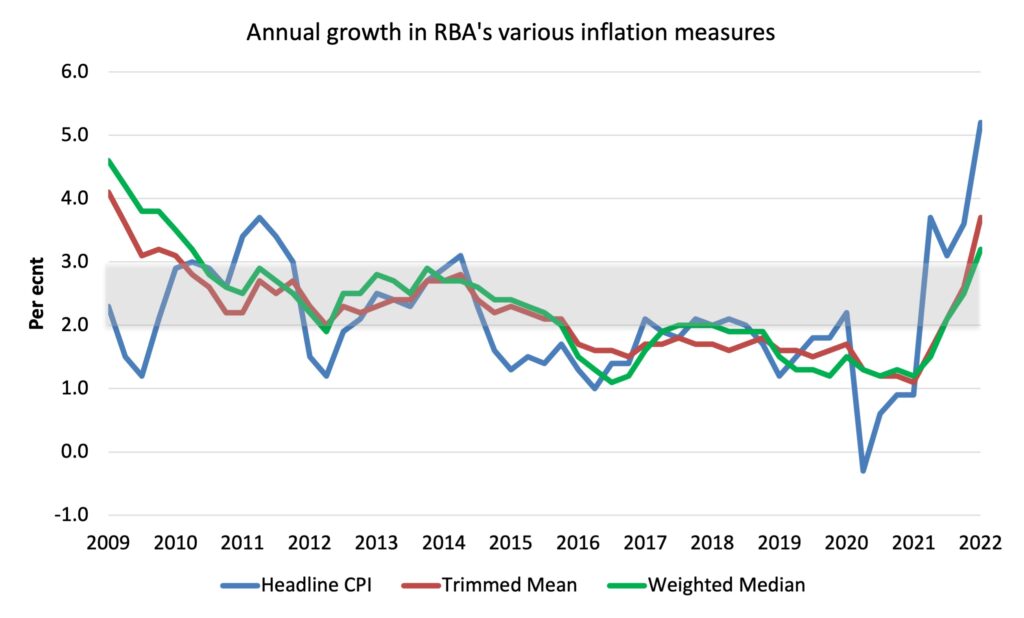

The following graph shows the three main inflation series published by the ABS since the March-quarter 2009 – the annual percentage change in the All items CPI (blue line); the annual changes in the weighted median (green line) and the trimmed mean (red line).

The RBAs inflation targetting band is 2 to 3 per cent (shaded area). The data is seasonally-adjusted.

The three measures are all currently below the RBA’s targetting range:

1. CPI measure of inflation rose by 5.1 per cent (up from 3.7 per cent last quarter).

2. The RBAs preferred measures – the Trimmed Mean was 3.7 per cent and the Weighted Median was 3.2 – moved outside the the RBAs targetting range for the first time since December 2009.

How to we assess these results?

1. The economy is starting to adjust to the hard supply constraints imposed by the pandemic.

2. Inflationary expectations are relatively contained, especially the most reliable indicator of long-term inflationary expectations.

3. The RBA has consistently said they will not increase rates until there is signs of wage pressures driving the show.

4. The RBA knows that with no wage pressures evidence, increasing interest rate rises will do nothing to grow forests more quickly to ease the timber shortage nor send a signal to OPEC to stop profit gouging. They also know that rate rises will do nothing to make ships deliver goods more quickly.

5. They know that if rising rates do anything they will worsen cost pressures on firms.

6. I don’t think they will hike rates in May.

Conclusion

The inflation rate in Australia is following world trends upwards, although it is still below the US levels.

The major sources of price increases are temporary – adjustments back to pre-pandemic levels, anti-competitive cartel behaviour and the War in Ukraine.

In Australia’s case, these influences are supplemented by shortages of building materials due to bushfires and soon the major floods (which will also impact on the food supply).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks Bill for the post. Can you please expand on the mechanisms by which the banks hope to capitalise on a rise in interest rates, or point me to such discussion? Thanks

@bruce, Net interest margin expansion a bit easier.

Given the high level of debt many people have and wage stagnation the reserve bank would be hesitant raising rates .

Bill- would you be interested in doing a post on US inflation? I’ve seen a lot of people saying US inflation is different than Europe/Australia in that it is demand driven and therefore rate hikes are justified. I’m curious about your perspective on that.

People are faced with increased costs for many goods and services arising from supply disruptions, cartel like behaviour and speculation and the response from the bankers is to call for higher interest rates which will further increase costs of goods and services. There is no talk from the bankers to try and address any of the supply side disruptions.

Over at The Guardian, Greg Jericho seems convinced that the RBA is about to begin hiking because of inflation in non-tradables.

I can’t see how it automatically follows that this means that wages must be growing strongly across the board and that a wage-price spiral is imminent – it probably just largely means that capital is generally in a position to do something most workers are not – at least attempt to immediately pass on any rising cost burdens by raising prices.

If only it were so easy for the average worker to raise their asking price accordingly.

This bout of inflation has nothing to do with an excess of money in the economy and it will not respond to a tightening in monetary policy/higher interest rates.

I read that the MMT solution to rising inflation is raising taxes. I’m interested to know more about how the politics of that could actually happen.

Low incomes are struggling to pay this year’s 8% extra cost for food staples. There are going to be some interesting politics coming from this demographic. Especially when they realise that even when/if inflation rates fall, these higher food prices are now permanent. Unless we get an 8% food deflation or higher wages for low income earners. Neither of which seem to be likely. MMT is rapidly getting out of it’s depth as a theory, as inflation permanently raises critical price levels.

Can I ask about a flight of capital if interest rates rise in the US but are not matched by Australia?

@ZoltanK

I’m uncertain as to how MMT is “getting out of it’s depth” – my laypersons observations since 2009 have shown it to be consistent with pretty much all major real world outcomes since that time, including the current inflationary episode.

It’s clear what the driving forces are and they are not government spending nor wage growth. It’s also clear that raising interest rates is unlikely to help and may instead spur more inflation through raising business costs.

It may be though that measures that could be taken to address this currently lie outside the realm of what is politically possible.

There is only one area where I would say that MMT is out of it’s depth – it has never had control of the narrative.

Australia is a country that is absolutely swimming in energy resources, with huge reserves of old-school sources – high-quality coal, gas, and (dare I mention it) uranium.

We are also absolutely drenched in intense sunlight and have much capacity for wind generation and other low-pollution sources.

Yet while being up to our armpits in electrical energy resources, we are now being told to brace ourselves for sharp hikes in the cost of electricity due in part to the instability arising in Europe and the fact that energy resources are a global market (I’m aware that there is more than just this). Hikes in the price of something as fundamental to economic activity as energy will run through the cost of everything in a similar way to petroleum.

How we could allow a country so wealthy in energy to be held hostage to global energy markets makes little sense to me.

I would gladly see government take control of pricing in the energy sector here – I’d be happy for them to own it – given it’s huge economic consequences. Yes, I am saying price controls.

Hi folks,

Labour is proposing a housing affordability policy where they would contribute up to $380k to your mortgage (taking an equity share of up to 40% I think…). I’d like to know if anyone has any information on how this has worked in other countries and if you think it may contribute to increased housing prices or add to inflationary pressures?

Drum roll……………what will the RBA do in an hour?

Steven Hail agrees with Bill that raising rates now is a very bad idea…….but thinks they are likely to do it anyway as they come under pressure from political/vested interests.

If they do go ahead and raise rates this afternoon their statement will make interesting reading. What would be the impetus? Do they have advance knowledge of wage figures? Maybe trying to prevent the $AUSD from depreciating against the majors who have been raising their rates? The RBA already previously noted that despite the shock to commodity prices from the war in Eastern Europe, Australia is a major exporter of most of those same commodities which I would think would help dampen any such effect. Also, if Europe eviscerates itself (as Euro-elites showed in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse that they are completely willing to inflict such actions on their populations) over Russian energy and other exports, surely the serious economic squeeze is likely to place downward pressure on the Euro? I see that despite the fact that major central banks have been raising rates, the $AUSD does not appear to have fared too badly against the $USD and has actually appreciated against the Euro since the war began.

Lets see what happens in an hour.

Yep, an increase in the cash rate – Steven was on the money.

The statement by the board seems to make it clear that they believe that they have evidence that wages growth is beginning to pick up broadly and that this is likely not a one-off rise but just the beginning of a series of rises.

Great move – workers are just beginning to get slightly back ahead……so lets crush that out with rate rises. Bravo.

For all the talk in recent years of waiting until inflation is sustainably within their target band, I think the RBA have jumped the shark and have lapsed back into the old mentality of seeing the foreboding shadow of a devastating wage-price spiral just around the corner.

I for one fail to see how – unions simply aren’t strong enough to engage in this tactic anymore.

Putting aside the emotional response to this – I think it will be interesting to learn more about this apparent wage growth. The RBA uses the term “liason with firms” to judge that wage costs are now broadly beginning to rise – one might expect that they would also liaise with workers representatives in order to gain a clearer understanding of exactly what is occurring. I don’t see evidence that they actually do this. The question in my mind is: are workers “winning” pay rises – or has business finally accepted that in a tight labour market, they may need to offer better in order to attract the labour they require?

If it is the former then they might possibly be able to argue some justification. I would still say it’s too early but at least that might be an argument.

But if it’s the latter then we may be already approaching the point where the labour market isn’t likely to get all that much tighter. My experience leads me to conclude that in at least the lower half of the labour market (probably lower two-thirds even) firms today tend to have a monopsony and it is they who largely set the price of labour, outside basic wage decisions by policy makers. Ergo, workers would have not suddenly (magically) regained the industrial might they possessed in the 70’s but rather, business has grudgingly accepted that they need to pay a bit more to attract/retain labour in a currently tight market – if that were the case then workers are still not driving this increase and still do not possess the power to strongly push up wages across the broader labour market. Meaning that business will pay rises of the size and frequency that it thinks it absolutely has to and no more.

My suspicion is that the RBA has misinterpreted business concluding that granting wage rises are in it’s own interests when the labour market is as tight as it is as workers actually “winning” pay rises and believes that they will continue winning and tip the economy toward a wage-price spiral.

But as always, more data over time will make things clearer.

@’Bruce Daniel’ you wrote:

April 27, 2022 at 13:42

“Thanks Bill for the post. Can you please expand on the mechanisms by which the banks hope to capitalise on a rise in interest rates, or point me to such discussion? Thanks”

The mechanism is they write “15%” on your loan agreement instead of “10%”. With a pen, or computer. Banks profit off a spread above the Central Bank floor rate. The spread they can get away charging customers with is market determined, but customers find it disagreeable to switch banks, so the bank will get away with adding as much mark-up as they see fit.

… but you should check for Law in your country that prohibits banks from charging arbitrary high rates above the floor rate. But up to that maximum they will likely disregard customer welfare until they think they will risk bleeding customers.