Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

US labour market recovery continues but still 7,629 thousand jobs short from February 2020

Last Friday (June 4, 2021), the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released their latest labour market data – Employment Situation Summary – May 2021 – which showed that the recovery since the catastrophic labour market collapse in March and April 2020, continues after a moderate month in April 2021. Payroll employment rose by 559,000 in May 2021 after rising by only 266 thousand last month. The slight rise in unemployment last month gave way to a fall in the unemployment rate by 0.3 percentage points to 5.8 per cent. edged up slightly to 6.1 per cent. The broader labour wastage captured by the BLS U6 measure fell by 0.2 points to 10.2 per cent. The US labour market is still 7,629 thousand jobs short from where it was at the end of February 2020.

Overview for May 2021:

- Payroll employment increased by 559,000.

- Total labour force survey employment rose by 444 thousand net (0.29 per cent).

- The seasonally adjusted labour force fell by 53 thousand (-0.03 per cent).

- Official unemployment fell by 496 thousand to 9,316 thousand.

- The official unemployment rate fell by 0.3 points to 5.8 per cent.

- The participation rate fell by 0.1 points at 61.6 per cent.

- The broad labour underutilisation measure (U6) fell by 0.2 points to 10.2 per cent.

For those who are confused about the difference between the payroll (establishment) data and the household survey data you should read this blog post – US labour market is in a deplorable state – where I explain the differences in detail.

BLS explanation of COVID effects on data

The BLS say:

As in previous months, some workers affected by the pandemic who should have been classified as unemployed on temporary layoff were instead misclassified as employed but not at work. However, the share of responses that may have been misclassified was highest in the early months of the pandemic and has been considerably lower in recent months. Since March 2020, BLS has published an estimate of what the unemployment rate might have been had misclassified workers been included among the unemployed. Repeating this same approach, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in May 2021 would have been 0.3 percentage point higher than reported. However, this represents the upper bound of our estimate of misclassification and probably overstates the size of the misclassification error.

So we are now operating in an environment of minimal uncertainty.

Payroll employment trends

The BLS noted that:

Total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 559,000 in May, following increases of 278,000 in April and 785,000 in March. In May, nonfarm payroll employment is down by 7.6 million, or 5.0 percent, from its pre-pandemic level in February 2020. Notable job gains occurred in leisure and hospitality, in public and private education, and in health care and social assistance in May …

In May, employment in leisure and hospitality increased by 292,000, as pandemic-related restrictions continued to ease in some parts of the country … Employment in leisure and hospitality is down by 2.5 million, or 15.0 percent, from its level in February 2020.

In May, employment increased in public and private education, reflecting the continued resumption of in-person learning and other school-related activities in some parts of the country … However, employment is down from February 2020 levels in local government education (-556,000), state government education (-244,000), and private education (-293,000).

Health care and social assistance added 46,000 jobs in May … Compared with February 2020, employment is down by 508,000 in health care and by 257,000 in social assistance.

Employment in information rose by 29,000 over the month but is down by 193,000 since February 2020.

Manufacturing employment rose by 23,000 in May … Employment in manufacturing is down by 509,000 from its level in February 2020.

Transportation and warehousing added 23,000 jobs in May … Since February 2020, employment in transportation and warehousing is down by 100,000.

Employment in wholesale trade increased by 20,000 in May, mostly in the durable goods component (+14,000). Employment in wholesale trade is down by 211,000 since February 2020.

Construction employment edged down in May (-20,000), reflecting a job loss in nonresidential specialty trade contractors (-17,000). Employment in construction is 225,000 lower than in February 2020.

Employment in professional and business services changed little in May (+35,000) … Overall, employment in professional and business services is down by 708,000 since February 2020.

Employment in retail trade changed little in May (-6,000) … Employment in retail trade is 411,000 below its February 2020 level.

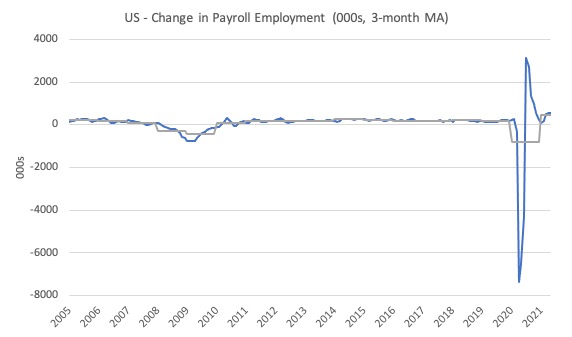

The first graph shows the monthly change in payroll employment (in thousands, expressed as a 3-month moving average to take out the monthly noise). The gray lines are the annual averages.

The data swings are still large and dwarf the past history.

Clearly, the 559,000 jobs gain (net) in April represents a substantial improving on what we saw in March.

The US labour market is still 7,629 thousand jobs short from where it was at the end of February 2020.

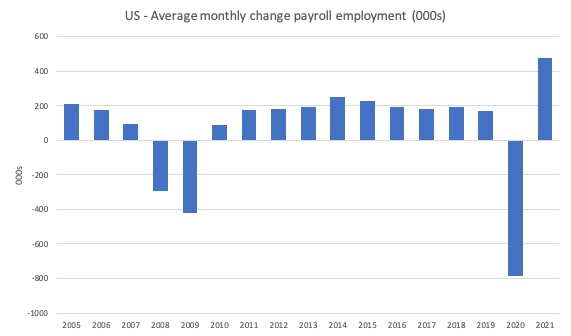

The next graph shows the same data in a different way – in this case the graph shows the average net monthly change in payroll employment (actual) for the calendar years from 2005 to 2021.

The final average for 2019 was 168 thousand.

The final average for 2020 was -785 thousand.

The average for 2021 (so far) is 478 thousand.

Labour Force Survey – employment grows but labour force contracts

The data for May reveals:

1. Employment as measured by the household survey rose by 444 thousand net (0.29 per cent).

2. The labour force fell by 53 thousand (-0.03 per cent).

3. The participation rate fell by 0.1 points to 61.6 per cent.

4. As a result (in accounting terms), total measured unemployment fell by 496 thousand to 9,316 thousand and the unemployment rate fell from 6.1 per cent to 5.8 per cent.

The BLS note that both unemployment measures:

In May, the unemployment rate declined by 0.3 percentage point to 5.8 percent, and the number of unemployed persons fell by 496,000 to 9.3 million. These measures are down considerably from their recent highs in April 2020 but remain well above their levels prior to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (3.5 percent and 5.7 million, respectively, in February 2020) …

The labor force participation rate was little changed at 61.6 percent in May and has remained within a narrow range of 61.4 percent to 61.7 percent since June 2020. The participation rate is 1.7 percentage points lower than in February 2020. The employment-population ratio, at 58.0 percent, was also little changed in May but is up by 0.6 percentage point since December 2020. However, this measure is 3.1 percentage points below its February 2020 level.

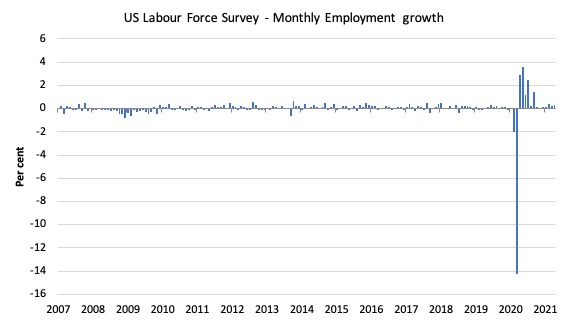

The following graph shows the monthly employment growth since January 2008, which shows the massive disruption this sickness has caused.

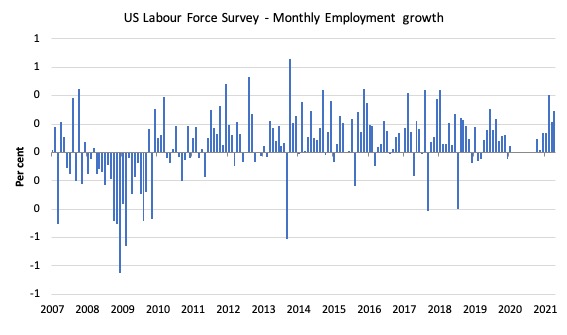

To put the recent period in perspective I took out the extreme observations (outliers) between March 2020 and October 2020 and repeated the graph.

This graph shows the current recovery more realistically.

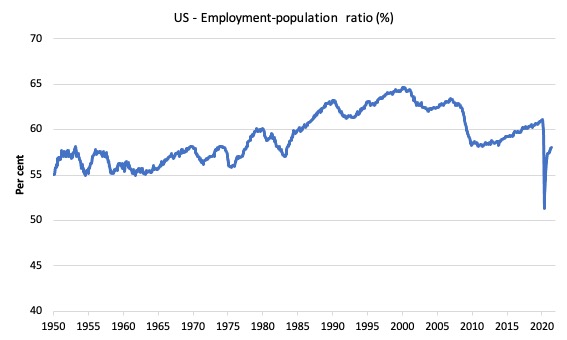

The Employment-Population ratio is a good measure of the strength of the labour market because the movements are relatively unambiguous because the denominator population is not particularly sensitive to the cycle (unlike the labour force).

The following graph shows the US Employment-Population from January 1950 to May 2021.

While the ratio fluctuates a little, the April 2020 ratio fell by 8.6 points to 51.3 per cent, which is the largest monthly fall since the sample began in January 1948.

In May 2021, the ratio rose by 0.1 points to 58 per cent.

It is still well down on the level in February 2020 (61.1 per cent).

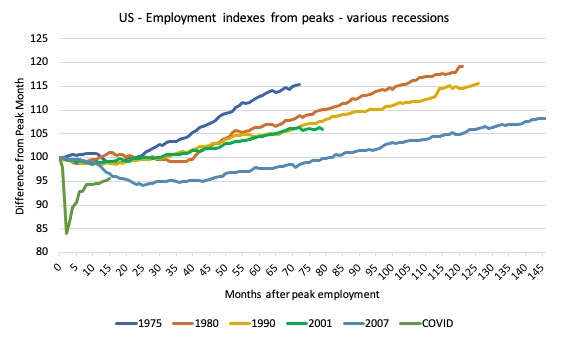

As a matter of history, the following graph shows employment indexes for the US (from US Bureau of Labor Statistics data) for the five NBER recessions since the mid-1970s and the current 2020-COVID crisis.

They are indexed at the employment peak in each case and we trace the data out for each episode until one month before the next peak.

So you get an idea of:

1. The amplitude (depth) of each cycle in employment terms.

2. The length of the cycle in months from peak-trough-peak.

The early 1980s recession was in two parts – a short downturn in 1981, which was followed by a second major downturn 12 months later in July 1982 which then endured.

Other facts:

1. Return to peak for the GFC was after 78 months.

2. The previous recessions have returned to the 100 index value after around 30 to 34 months.

3. Even at the end of the GFC cycle (146 months), total employment in the US had still only risen by 8.3 per cent (since December 2007), which is a very moderate growth path as is shown in the graph.

The COVID collapse was something else but the recent gains are evident, although the gains have been slowing relative to early in the recovery.

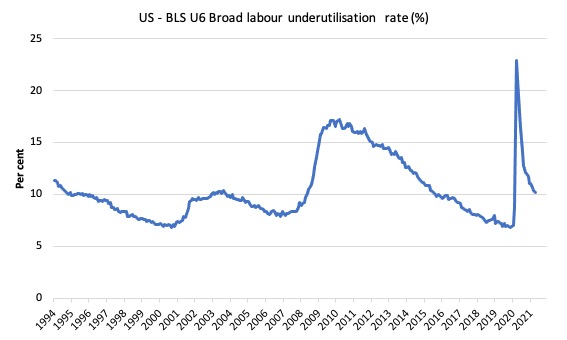

Unemployment and underutilisation trends

The first graph shows the official unemployment rate since January 1994.

The official unemployment rate is a narrow measure of labour wastage, which means that a strict comparison with the 1960s, for example, in terms of how tight the labour market, has to take into account broader measures of labour underutilisation.

The next graph shows the BLS measure U6, which is defined as:

Total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of all civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers.

It is thus the broadest quantitative measure of labour underutilisation that the BLS publish.

Pre-COVID, U6 was at 6.8 per cent (December 2019).

In May 2021 the U6 measure was 10.2 per cent, a decline of 0.2 points on the previous month.

The part-time for economic reasons cohort (the US indicator of underemployment) fell by 28 thousand (0.5 per cent), a substantial reduction in the recent monthly changes in underemployment.

The BLS say that:

The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons was essentially unchanged at 5.3 million in May but is 873,000 higher than in February 2020. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs …

In May, the number of persons not in the labor force who currently want a job was essentially unchanged over the month at 6.6 million but is up by 1.6 million since February 2020. These individuals were not counted as unemployed because they were not actively looking for work during the last 4 weeks or were unavailable to take a job …

Among those not in the labor force who currently want a job, the number of persons marginally attached to the labor force, at 2.0 million, changed little in May but is up by 518,000 since February 2020. These individuals wanted and were available for work and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months but had not looked for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey. The number of discouraged workers, a subset of the marginally attached who believed that no jobs were available for them, was 600,000 in May, little changed from the previous month but 199,000 higher than in February 2020 …

Ethnicity and Education

The next graph shows the evolution of unemployment rates for three cohorts based on educational attainment: (a) those with less than high school completion; (b) high school graduates; and (c) university graduates.

As usual, when there is a crisis, the least educated suffer disproportionately.

In the collapse in employment, the unemployment rates rose by:

- 14.1 points for those with less than high-school diploma.

- 13.0 points for high school, no college graduates.

- 5.9 points for those with university degrees.

The period since April 2020 has seen the unemployment rate fall by:

- 11.9 points for those with less than high-school diploma meaning the unemployment rate is now 3.8 points above the March level.

- 10.5 points for high school, no college graduates meaning the unemployment rate is now 4.6 points above the March level.

- 5.2 points for those with university degrees meaning the unemployment rate is now 2.3 points above the March level.

In the last month, the change in the unemployment rate has been:

- fall of 0.2 points for those with less than high-school diploma – so this cohort is bearing the cost of the stalled recovery.

- fall of 0.1 points for high school, no college graduates.

- fall of 0.3 points for those with university degrees.

In the US context, the trends in trends in unemployment by ethnicity are interesting.

Two questions arise:

1. How have the Black and African American and White unemployment rate fared in the post-GFC period?

2. How has the relationship between the Black and African American unemployment rate and the White unemployment rate changed since the GFC?

Summary:

1. All the series move together as economic activity cycles. The data also moves around a lot on a monthly basis.

2. The Black and African American unemployment rate was 6.8 per cent in March 2020, rose to 16.7 per cent in May and is at 9.1 per cent in May 2021. In the last month, it fell by 0.6 points.

3. The Hispanic or Latino unemployment rate was 6 per cent in March 2020, rose to 18.9 per cent in April and fell to 7.3 per cent in May 2021. In the last month, it fell by 0.6 points.

4. The White unemployment rate was 3.9 per cent in March 2020, rose to 14.1 per cent in April and fell to 5.1 per cent in May 2021. In the last month, it fell 0.2 points.

So the fall in unemployment in the last month has been shared across the ethnic groups.

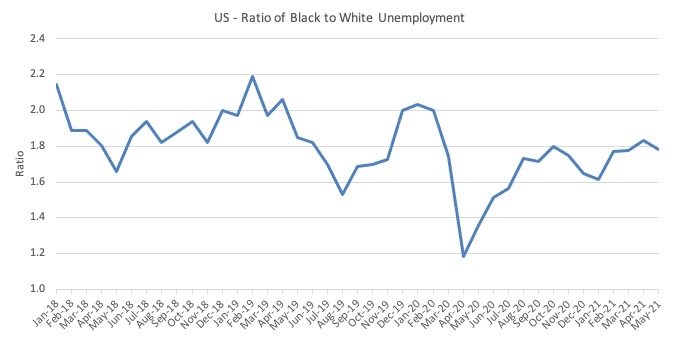

The next graph shows the Black and African American unemployment rate to White unemployment rate (ratio) from January 2018, when the White unemployment rate was at 3.5 per cent and the Black or African American rate was at 7.5 per cent.

This graph allows us to see whether the relative position of the two cohorts has changed since the crisis.

If it is rising, then the unemployment rate of the Black and African American cohort is either rising faster than the white unemployment rate or falling more slowly (or a combination of that relativity).

While there is month-to-month variability, the data shows that, in fact, through to mid-2019, the position of Black and African Americans had improved in relative terms (to Whites), although that just reflected the fact that the White unemployment was so low that employers were forced to take on other ‘less preferred’ workers if they wanted to maintain growth.

In April 2019, the ratio was 2.1 (meaning the Black and African American unemployment rate was more than 2 times the White rate).

By April 2020, the ratio had fallen to its lowest level of 1.2, reflecting the improved relative Black and African American position.

As the pandemic hit, the ratio rose and peaked at 1.8 in October 2020.

In May 2021, the ratio was 1.78 – a fall of 0.05 points from the previous month.

Additional feature this month: Wage movements

I have been working on detailing whether there is an inflation threat emerging in the US.

One of the ways of assessing whether the US economy is close to full employment is to examine the growth in wages, which tells us whether the supply-side of the labour market (workers) is enjoying gains in bargaining power.

The other indicator is the rate at which workers are quitting their jobs, which provides a signal of mobility and confidence among workers. The most recent data is not yet available.

The BLS reported that:

Average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls increased by 15 cents to $30.33 in May, following an increase of 21 cents in April. Average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees rose by 14 cents to $25.60 in May, following an increase of 19 cents in April. The data for the last 2 months suggest that the rising demand for labor associated with the recovery from the pandemic may have put upward pressure on wages. However, because average hourly earnings vary widely across industries, the large employment fluctuations since February 2020 complicate the analysis of recent trends in average hourly earnings.

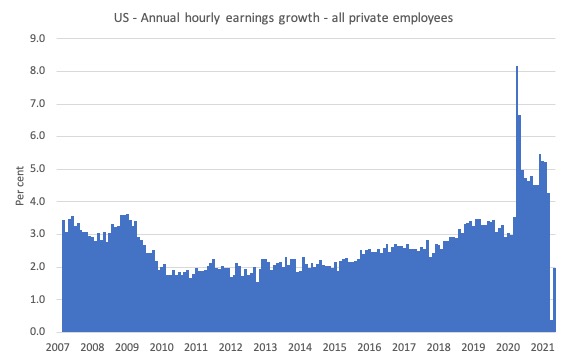

The following graph shows the annual hourly earnings growth for all private employees since March 2007.

The recent trend is downwards and dispels any notion that the US has reached the end of their expansionary capacity.

Noting that the above graph is in nominal terms.

The – BLS Real Earnings Summary (published May 12, 2021) – tells us that:

Real average hourly earnings for all employees were unchanged from March to April, seasonally adjusted … This result stems from an increase of 0.7

percent in average hourly earnings offset by an increase of 0.8 percent in the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). …Real average weekly earnings increased 0.2 percent over the month due to the change in real average hourly earnings with an increase of 0.3 percent in the average workweek.

And, from the latest – Productivity and Costs, First Quarter 2021, Revised (published June 3, 2021) – report, we find that:

Nonfarm business sector labor productivity increased 5.4 percent in the first quarter of 2021 … as output increased 8.6 percent and hours worked increased

3.0 percent.

So real hourly earnings growth is still lagging behind the annual productivity growth, which is another sign of labour market slack and weak bargaining power.

The following graph shows movements in real average hourly earnings (indexed at 100 the pre-GFC peak – November 2006) up to April 2021.

The faster growth as the recovery gained speed ended in early 2016

The spike in the early period of the pandemic was the result of hours adjustments rather than earnings growth.

Conclusion

The May 2021 US BLS labour market data release suggests that the April figures were a blip and the recovery continues on track.

It is clear though that the US labour market is still 7,629 thousand jobs short from where it was at the end of February 2020.

And while unemployment has fallen in the last month, there is no sign of wage pressures accelerating.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I don’t want to beat a dead horse (or do anything to harm any creature) but I’m too damn old to give much credence to ANY employment analysis that ignores or glosses over–indeed, does not highlight in the boldest colors–what passes for “employment” today vs. the plethora of solid, secure, decent-paying jobs I knew from childhood to middle age. I’m not saying in the slightest that Bill has avoided this issue–he’s addressed it time and time again–but IT remains the issue we should be focused on like a laser, NOT whether predominantly gig or temp or on-call “employment” goes up or down in this or that phase of what has devolved into obvious and obscene wage-slavery.