I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

UK productivity slump is a demand-side problem

I have recently had discussions with a PhD student of mine who was interested in exploring the cyclical link between productivity growth and the economic cycle in the context of the intergenerational debate about ageing and the challenge to improve the former. The issue is that sound finance – the mainstream macroeconomics approach – constructs the rising dependency ratio as a problem of government financial resources (not being able to afford health care and pensions) and prescribes fiscal austerity on the pretext that the government needs to save money to pay for these future imposts. Meanwhile, the real challenge of the rising dependency is that the next generation will have to be more productive than the last to maintain real standards of living and if austerity undermines productivity growth then it just exacerbates the ageing problem. My contention has always been the latter. That governments should use their fiscal capacity now to make sure there is a first-class education and training system in a growth environment to prepare us for the future when more people will have passed the usual concept of working age. This question also is hot at the moment in the Brexit debate in Britain and in this blog post I offer some empirical analysis to clear away some of the myths that the Remainers have been spreading.

In August 2019, the Bank of England released a Staff Working Paper No. 818 – The impact of Brexit on UK firm – uses the Bank’s Decision Maker Panel dataset, to “assess the impact of the June 2016 Brexit referendum on labour productivity, the principal causal mechanism being conjectured is that rising uncertainty has “gradually reduced investment by about 11% over the three years following the June 2016 vote”, which then undermines productivity growth.

In that paper, they make several claims, many of which are unable to be statistically verified, even when using their own results.

For example, they seek to “examine the impact of Brexit exposure on firms’s investment and employment” and say that, in relation to employment, that:

… the results are all negative but none are statistically significant. Therefore, whilst there is some tentative evidence that the Brexit process has led to lower employment, the finding is less robust than for investment.

That statement cannot be made.

The fact is that the regression estimates relating the Brexit variables in their model to employment are, in statistical terms, not different from zero – meaning there is no statistically robust negative impact.

Their results establish that there has been zero impact according to their dataset.

So any further attempts “to quantify the magnitudes of the reductions in … employment that have occurred in anticipation of Brexit” are spurious and should be disregarded.

Another example, is that they:

… report the IV estimates for the impact of the Brexit process on firm level productivity. In all cases we see a negative impact, which is significant in the OLS estimates, but not in the IV estimate.

What does that mean?

IV is the estimation technique, instrumental variables, which is deployed instead of OLS (ordinary least squares), when there is the prospect that the explanatory variables are jointly generated by the same processes that generate the variable to be explained.

Which means that OLS is an invalid estimation technique and IV is used to produce what we call ‘consistent’ estimates. In this case, if the IV estimates in question are not ‘statistically significant’, then there is no relationship discovered.

So the rest of their analysis in this regard is highly questionable.

Which means that the Financial Times article (August 31, 2019) – Brexit has cut UK productivity by up to 5%, says BoE – is unjustified in claiming that:

Brexit has caused British companies exposed to Europe to cut investment plans significantly and has cut UK productivity by between 2 and 5 per cent, according to Bank of England research.

At least without drawing attention to the econometric issues that the paper raises.

I was, however, interested in the Bank’s Survey Data that the paper used.

The most recent data is for – June 2019.

The Bank says that:

The panel comprises Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) from small, medium and large UK companies operating in a broad range of industries and is designed to be representative of the population of UK businesses. The panel has grown rapidly since its inception in August 2016, reaching around 8,000 firms by June 2019. The response rate has been around 40% in recent surveys.

The results are interesting:

1. In September 2016, 37 per cent of the sample said that Brexit as a source of uncertainty was just “One of many sources” that proportion is now (between February 2019 and April 2019), 33 per cent.

9 per cent said it was the ‘main source currently’ in September 2016, and now 21 per cent. A year ago it was 8 per cent. So the rise in uncertainty is more about the process it seems.

2. Between November 2016 and January 2017, there was a 73 per cent probability derived from the sample that the ‘Expected impact of Brexit on foreign sales by 2020’ would either increase or have no material impact (40 per cent for the latter).

Between May 2018 and July 2018, the probability of no material impact had risen to 48 per cent (and 62 per cent for the increase or no impact).

The main rise in the reduced sales probability was in the “less than 10% category”.

3. In terms of the ‘Expected impact of Brexit on capital expenditure over the next year’, the average probability in October 2016 was 57 per cent (no impact), 18 per cent (less than 5 per cent reduction), 16 per cent (more than 5 per cent reduction).

The most recent estimate (November 2018 to January 2019) has those probabilities at 59 per cent (no impact), 18 per cent (less than 5 per cent reduction), 15 per cent (more than 5 per cent reduction).

So the negative outcomes are stable and the no impact probability, despite all the chaos and mishandling of the process has actually risen.

That brings into question the Project Fear scenarios.

Either the respondents are lying or the Financial Times is exaggerating.

4. The average probability (%) of an ‘Expected impact of eventual Brexit deal on sales’:

– February 2017 and April 2017: 39 per cent (Make little difference), 13 per cent (Adding less than 10%), 6 per cent (Adding more than 10%).

– February 2019 and April 2019: 51 per cent (Make little difference), 8 per cent (Adding less than 10%), 4 per cent (Adding more than 10%).

A substantial rise in those who don’t think there will be an issue.

5. Most of the other Brexit-related questions have provided no data until now.

One interesting result (for which there is just one observation) was that the between February 2019 and April 2019, 70 per cent of the respondents said that the “Impact of Brexit so far on overall investment” had “No material impact”.

Now clearly, if we are talking about changes in investment behaviour then a stable majority does not exclude negative results emerging if the minority are negative.

6. The Survey also provides measures of uncertainty both across and within companies by employment, sales and price growth.

The fact is there is hardly any movement in any of these measures since the first Survey (November 2016 to January 2017). If uncertainty was on the rise then

Project Fear continues

Project Fear continues, albeit in a slightly more subdued manner, given, I suppose because of the massive predictive failures of the initial ‘the sky is falling’ campaign that the Remainers assailed the British people with.

Now, there is some circumspection disguising the disaster scenarios.

First, note that the latest GDP figures from the Office of National Statistics for the July National Accounts update

that (Source):

Gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 0.3% in July 2019.

The services sector (around 80 per cent of the total GDP output) grew by 0.3 per cent, and manufacturing and construction increased by 0.3 per cent and 0.5 per cent, respectively. The Index of Production rose overall by 0.1 per cent.

A ‘swallow does not a summer make’, meaning in this context, we should never rely on a single month’s observation.

But the Project Fear story that disaster is unfolding due to Brexit seems to keep getting inconveniently derailed by the actual data.

Second, an example of the more cautious version of Project Fear was the UK Guardian article (September 5, 2019) – The promised Tory tax cuts will only mean more austerity in the long run – written by the mainstream economist Simon Wren-Lewis.

I don’t wish to critique the whole article because it runs the ludicrous argument that if the British government uses fiscal stimulus now to offset the damage that Brexit might cause, eventually, and without doubt, further spending cuts will have to be made and austerity will be resumed.

He also claims that any plans to cut taxes would be dangerous because any “fiscal stimulus should be temporary, so that any consequent increase in the deficit comes to an end”.

So underpinning his logic is a belief in a balanced fiscal state, seemingly irrespective of the state of the non-government spending and income balance.

With an ongoing external deficit, if the British government targets a fiscal balance and succeeds in achieving that, then it is forcing the private domestic sector, already heavily indebted, to run deficits equal to the external deficit.

If the private domestic sector resisted that pressure and wanted to, for example, save overall, then the government pursuit of fiscal balance would drive the economy into recession.

But then the mainstream economists seem oblivious to these sorts of dynamics and fail to understand that for a country with an external deficit, the most likely sustainable position for government is to run on-going deficits in order to finance income growth and private domestic overall saving aspirations.

The point I want to focus on that came up in that article, and is a growing narrative among mainstream economists, is his claim that:

… the Bank of England … suspects that current weak growth reflects a deterioration in supply, not a lack of demand. A recent Bank of England study suggested that the collapse of investment since the referendum may have reduced productivity by between 2% and 5% from what it otherwise would have been. A fall in productivity of that size could well result in today’s flat growth.

Here we have the problem of causality.

First, has there been a collapse in British investment? And if so, has this been the result of the Brexit referendum?

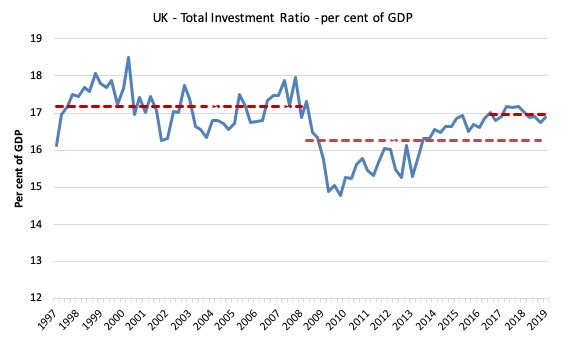

The first graph shows the Total British investment ratio (sum of Business and General Government capital formation) as a per cent of GDP from the first-quarter 1997 to the first-quarter 2019.

The dotted read lines are the average ratios before the GFC and after and for the Post-Referendum period (from the September-quarter 2016).

It is clear that a mean shift occurred during the GFC in capital formation in the UK. There is also some evidence of a slight further reduction in the ratio post Referendum.

But this is because the rise in GDP (the denominator) has outstripped the numerator (Capital formation).

The investment ratio is, on average, higher in the Post-Referendum period than for the Post-GFC period overall.

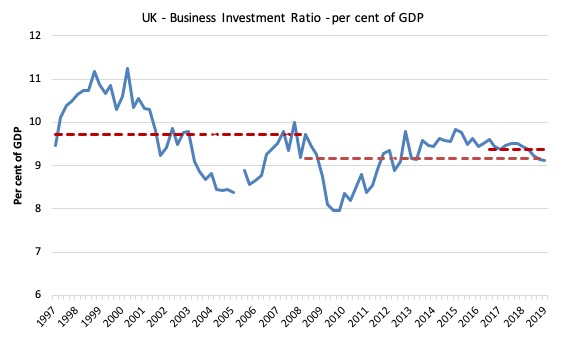

The next graph shows the Business investment ratio as a per cent of GDP from the first-quarter 1997 to the first-quarter 2019. Clearly given the dominance of business investment (more than 3 times general government expenditure), this series drives the dynamics for the previous total series shown above.

The following facts apply when we concentrate on real expenditure (rather than the ratio):

1. Real expenditure on Total Capital formation rose, on average, by 3.4 per cent per annum from 1997 to the March-quarter 2008.

2. In the Post-GFC period it rose by 0.9 per cent per annum on average.

3. In the Post-Brexit period, it rose, on average, by 2 per cent per annum.

4. Since the June-quarter 2016, that is, in the Post-Referendum period, real business investment has slowed but is still, on average, growing. Thus trying to tell UK Guardian readers that it has ‘collapsed’ is simply false.

5. It is true that growth in real Business investment has contracted in the last three quarters but real capital formation in the general government sector has accelerated, ensuring total investment in the British economy has continued to deliver positive growth.

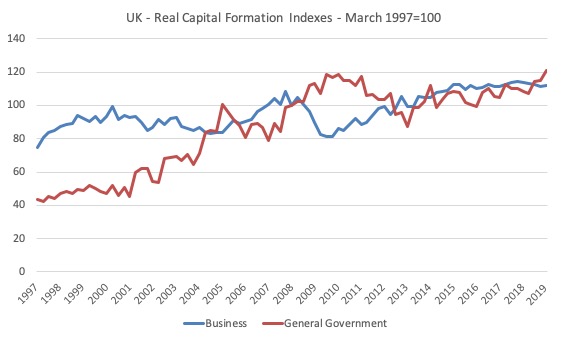

The next graph shows the evolution of real capital formation from the March-quarter 1997 to the March-quarter 2019, where the index is set to 100 in the March-quarter 2008 (so at the turning point of the cycle).

I deleted the observations for the second-quarter 2005, which saw a huge upward spike in private business investment and a corresponding fall in public capital formation as a result “of the transfer of British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL). In April 2005, nuclear reactors were transferred from BNFL to the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA). BNFL is classified as a public corporation in National Accounts, while the NDA is a central government body. The business investment series includes investment by public corporations but not government spending, with the positive spike therefore reflecting the £15.6 billion transfer.”

The GFC stimulus and fiscal austerity is clearly shown (red line) as is the sharp decline in the growth in business investment and the slow recovery post trough.

But real Business investment started to stall in 2014 as the fiscal austerity started to really impact on the economy. That is some years before the Referendum and reflects poor conditions in the economy overall, rather than angst over leaving the EU.

Why does this matter?

Claims that productivity slumps are the reason for slow growth almost assuredly put the cart before the horse.

It is clear that capital formation slumped dramatically as the GFC hit and drove the collapse in real GDP growth.

Spending creates income (and output).

For more analysis of this issue, see the blog post – British productivity slump – all down to George Osborne’s austerity obsession (October 18, 2017).

The consequences the investment behaviour are not solely the short-run spending loss. Capital formation adds to the supply-side of the economy and is a major driver of productivity.

So we get a more likely causality – GFC erodes confidences, capital expenditure drops, GDP drops as a consequence, and the slowdown in capacity building impacts negatively on productivity growth.

Solution – stimulate spending.

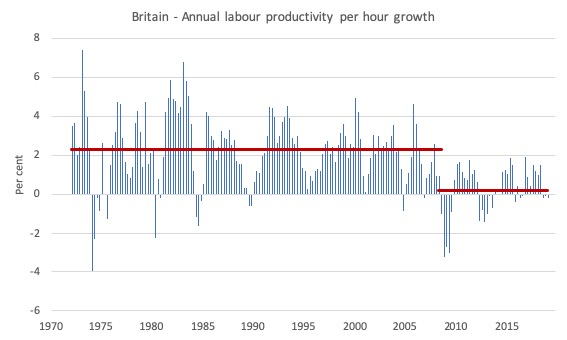

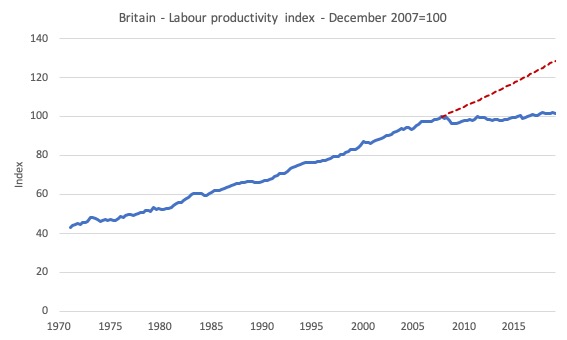

The first graph shows the annual growth in output per hour worked (labour productivity) from the March-quarter 1971 to the March-quarter 2019.

The red horizontal lines are the average rates of growth Pre- and Post-GFC.

The mean shift in growth occurred as a result of the GFC and the poor policy response that followed.

The next graph shows this data in a different way by tracing the evolution of output per hour worked (labour productivity) from the March-quarter 1970 to the March-quarter 2019.

The dotted line is an extrapolation of the Pre-GFC trend rate of growth.

The productivity growth slump happened as a result of the GFC. Brexit has really had nothing to do with it (although it is plausible it may turn out to be a second negative shock on an already flat series).

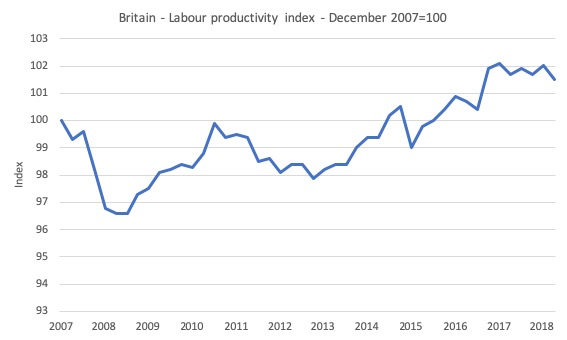

The final graph zooms in on the Post-GFC period (from the December-quarter 2007) to get a better feel for the behaviour of productivity in this period.

We see the decline as the GFC erodes output growth, the improvement as the fiscal stimulus starts to work to buttress renewed growth, then the George Osborne austerity push from mid-2010 creating further negative productivity shocks and then the subsequent, slow, drawn out recovery.

Don’t be fooled by the vertical scale. The overall period is best described as being very flat growth. Overall, the index has risen only 1.5 index points since the December-quarter 2007 – in other words hardly at all.

But almost all that increase has come in the Post-Brexit period, which further casts doubt on Project Fear’s disaster scenarios.

The point is that the productivity slump was driven by the GFC.

Structural explanations of this slump are also unlikely to have traction. The massive cyclical contraction pushed British productivity growth of its past trend. Structural factors work more slowly and we would not witness such a sharp fall if they were implicated.

Why would that cause productivity growth to slumplike it did, then fail to recover?

A major driver of productivity is investment spending – both public and private.

While business investment is cost sensitive (so may respond to interest rate changes), mainstream economists usually ignore the fact that expectations of earnings are also important as are asymmetries across the cycle.

Cyclical asymmetries mean (in this context) that investment spending drops quickly when economic activity declines and typically takes a longer period to recover. So fast drop and slow recovery.

The cyclical asymmetries in investment spending arise because investment in new capital stock usually requires firms to make large irreversible capital outlays.

Capital is not a piece of putty (as it is depicted in the mainstream economics textbooks that the students use in universities) that can be remoulded in whatever configuration that might be appropriate (that is, different types of machines and equipment).

Once the firm has made a large-scale investment in a new technology they will be stuck with it for some period.

In an environment of endemic uncertainty, firms become cautious in times of pessimism and employ broad safety margins when deciding how much investment they will spend.

Accordingly, they form expectations of future profitability by considering the current capacity utilisation rate against their normal usage.

They will only invest when capacity utilisation, exceeds its normal level. So investment varies with capacity utilisation within bounds and therefore productive capacity grows at rate which is bounded from below and above.

The asymmetric investment behaviour thus generates asymmetries in capacity growth because productive capacity only grows when there is a shortage of capacity.

This insight has major implications for the way in which economies recover and the necessity for strong fiscal support when a deep recession is encountered.

These dynamics are covered in my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned.

In some of my earlier work (with Joan Muysken) – for example, here is a working paper you can get for free (subsequently published in the literature) – we developed a model based on the notion that investors facing endemic uncertainty make large irreversible capital outlays, which leads them to be cautious in times of pessimism and to use broad safety margins.

The problem of asymmetry can be attenuated if government steps in during a downturn and arrests the spending collapse. Appropriate fiscal stimulus initiatives can thus shorten any non-government spending declines and limit the investment slump.

This not only shortens the decline into the activity trough but also means that potential output growth can be maintained at previous rates.

The opposite is of course also the case.

Imposing pro-cyclical fiscal austerity of the scale that George Osborne initiated when the Tories came took government in May 2010 is the last thing a government should do when non-government spending is in retreat.

Fiscal austerity in these circumstances exacerbates the typical asymmetry associated with investment expenditure and is a major reason why business investment in the UK has been so weak.

We often focus on the short-term negative impacts of fiscal austerity, but in this case, it also has serious long-term impacts on both the rate of business investment and the potential growth rate (which falls as capital formation stalls).

The longer it takes for business investment to recover, the worse will be the long-term impact on potential GDP growth. In turn, this means that the inflation biases are increased because full capacity is reached sooner in a recovery – often before all the idle labour is absorbed.

So, while George Osborne is long gone, the negative impacts of his policy folly will reverberate for a long time to come. His failings will continue on for many years and the flat productivity growth is one manifestation of that failing.

Conclusion

The Brexit issue is clearly a source of uncertainty.

But it looks from the data to be of a second-order of importance relative to the on-going damage that the GFC and subsequent fiscal austerity caused.

Carping on about Brexit as the source of all ills in the British economy is a popular pastime for the urban elite Remainers.

But it is unlikely to produce a very meaningful narrative to help understand what is going on at present.

It also leads to ridiculous articles in the UK Guardian that suggest fiscal policy will not be very helpful in redressing the damage that poor fiscal conduct over several years, largely generated.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Over here we have The Conversation website providing support for Project Fear. There is no doubt they have been heavily biased in their coverage of this issue. It looks more and more like a subsidiary of The Guardian site with each passing day.

At last night’s AGM of the Dursley Labour Party I happened to mention MMT. The acting chairman asked what that was because she’d heard about it but not understood. I gave a short precis of the key principles I’d learned from this blog and emphasised the importance of ‘framing’ and how neoliberal framing had influenced the public understanding of economic matters. Afterwards the chairman thanked me and said that she now understood what it was about and how it was now crystal clear. She further suggested that we set up a group to discuss economic matters. I also plugged the reclaiming the state book. Thank You Bill, I think an acorn might have been planted here in the West Country.

Hi Bill,

I found the statistical errors in the BoE work you uncovered very disturbing.

While I know such institutions make numerous errors based on mainstream thinking all the time, I did not expect them to make such lazy and basic statistical reasoning errors in order to (it appears) confirm a pre-existing bias.

How serious do you think it is that these errors are being made by BoE staff?

Cheers,

Anthony

Let’s call a horse a horse. Someone with an education that depends on statistics courses can not get a degree while making those kinds of errors. They are bold faced lies to fit a political agenda.

Well project Fear in the last few weeks and months has been specifically directed against “No-Deal” Brexit, with the Liberal Democracts, SNP, and latterly Labour, shouting increasingly hysterically, in the Commons, and on Twitter.

As has been pointed out, even by the pro-establishment presenter of BBC’s Question Time, Labour’s position is laughably contradictory, as they claim to want to negotiate a new deal with the EU, which they will then campaign against in a new referendum campaign.

The seemingly permanently angry SNP MPs, led by Ian Blackford (a former banker – what else?), are complete humbugs. They rant and rave about the UK government dragging the Scots out of the EU against their will (ignoring the fact that 38% of Scots voted to Leave the EU). While at the same time, their declared policy, in fact their only raison d’être, is to leave the UK, despite the fact that over 55% of Scots voted to stay in the UK in 2014. It would serve the likes of Blackford right (although not the good Scots who were misled by him and his ilk), if Scotland were to achieve independence and independent membership of the EU and the Eurozone….and then be subject to the tender mercies of the Troika, just like Greece. They would soon be wailing to come back into the UK.

Then we have the Liberal Democrats. Now led by Jo Swinson, whose voting record on economic matters is horribly neoliberal. No surprise, since the Coalition taught us that the Liberal Democrats are a fundamentally neoliberal, pro-austerity party. “Democrats”? Some democrats. Swinson has been widely reported as saying that in a new EU referendum which she wants, if its comes back with people still wanting to Leave, she will just ignore it. Well, her party have ignored the first referendum, so I suppose at least they are consistent.

In both debates on an early election (which would have been the ultimate “people’s vote”), almost all Lib Dem MPs voted against it . Complete hypocrites, all. In answer to a question, Swinson said (from Hansard):

and later:

A Conservative member interjected:

But she evaded this question

Anyway, now Parliament is prorogued. Although the proroguing was not quite such an evilly unprecedented act as the hysteRemainers are pretending (John Major did it in 1997), it was probably a strategic and tactical error on Johnson’s part. He has given them more ammunition for their faux high moral stance.But anyway, what chances for Brexit happening now? What are the chances of a No Deal?

During his campaign for leadership of the Tory party, Johnson was sounding very gung-ho about this. This was probably to win over the ERG wing of his party, and to convince potential defectors to the Brexit party to stay with him. However, as time has moved on he seems to have talked less and less about no deal, and more and more about a deal, especially on his trip yesterday to Dublin, where he seemed rather subdued. People like Farage are increasingly concerned that his aim is to bring back a version of the May deal with the EU, which he regards as Brexit-in-name-only. What he might try for is to convert the “backstop” into a “backstop for Northern Ireland only”, i.e. leave NI within the Customs Union. This is what Barnier originally offered, but May turned it into “backstop for all of the UK” after pressure from the DUP. But the DUP is now irrelevent, given the new situation in Parliament.

Johnson has said that come what may, he will not ask the EU for a new extension beyond 31st October. This would appear to put him in breach of the new law that the Commons has just passed (A very bad law, like most laws passed in a hurry, and its makers may come to regret it). Whether he knows some subtle way around the law, or is just bluffing, we don’t know. It might mean he would resign, rather than do it, and then we are in uncharted waters. Or it might mean he would take a risk, and just disobey this law, and dare his opponents to take him to court, and perhaps lock him up. Again, we would be in uncharted waters if that were to happen. It could be that the legal action required would be so slow that the UK would still “crash out” (to use a favourite phrase of the hysteRemainers) of the UK.

oops, I meant “crash out” of the EU, of course. Mea culpa.

Great article.

Great to learn about when businesses perform capital formation.

The EU created several frameworks, the most fundamental one is the peace project. Other frameworks concern more narrow interests of the general population.

I agree there is no generally accepted empirical economic theory that explains what is actually going on in the contemporary society. I think that the emerging MMT is the closest to fulfill this task today.

I think it has been politically and scientifically damaging to mix the EU austerity and the EU membership issues. Unfortunately the contemporary media refuses to go deep enough in explaining social processes comprehensively. As a result all debating parties are reduced to simplified schemes. Only those soundbites are magnified which have stronger trigger effect on the audience.

I would avoid terms like “Project Fear” and “Brexit Folly”. The most basic fear is of the new wave of violence in Europe up to a major military conflict which the media and the hawkish politicians are continuously stirring up near all the foreign borders of the EU. Addressing the remainers as “Project Fear” will only highlight all the real threats people are facing and whip up emotions.

To add a personal note: I think that it would be more productive to aim at dismantling the Eurozone and starting the anti-austerity project in the whole EU than breaking single countries apart from the EU while creating political and media havoc that overshadow the real issues.

Sound finance requires sound accounting, yes?

Then how can we have sound finance when government privileges* for depository institutions, aka “the banks”, render their liabilities toward the non-bank private sector largely a sham**?

*Such as the government insurance of private ( including privately created(!) ) deposits/liabilities instead of inherently risk-free debit/checking accounts for all (or at least all citizens) at the Central Bank or Treasury itself.

** The liabilities of the banks are for fiat which the non-bank private sector may not even use except for mere physical fiat, paper bills and coins.

@Andri Ksenofontov,

The reason to focus on leaving is that to change the EU, all 28 members must agree. Note *ALL* members.

This is seen as being impossible, until they have no choice. Thus, if 1 or 2 leave and others threaten to leave then the last few hold outs may agree to some changes. This is seen by us as the only way to get the changes in the EU that are necessary.

What is necessary? Just my thoughts and I’m no expert.

1] Eliminate the euro and change the other economic rules.

OR,

2] Keep the euro, make the ECB sell bonds and then give the euros to all nations to finance their deficits and change the other economic rules. Obviously there would need to be some rules about how big a nation’s deficit can be, and this is the devil in the details.

OR.

3] Keep the euro, change the other economic rules, let all nations sell bonds in euros AND most important let them also create 1.1 or 2 or 3 times as many euros as the bonds they sell and just spend them into the economy. This number {1.1, 2, or 3 } would be the same for all nations and could be changed by the Eur. Parliament. Or, maybe 2 different numbers, one for Germany & UK, etc., and another for all the other poorer nations.

Just some crazy thoughts.

Excellent Bill simply superb.

And a fantastic contribution by Mike Ellwood. Mike sees it as clear as day and 99.9% of MMT’rs see it clearly apart from those who claim to be MMT’rs in Scotland. Who lie cheat and deceive to deny the truth. You can hear their echo as far away as Fiji as they shout their independence at all costs strategy with their heads stuck firmly up the arses of the SNP.

It has been 10 months and MMT Scotland still hasn’t produced a public paper on EU membership and what it means for an independent Scotland to be at the heart of Europe. Mark my words it will be a fudge filled with nonsense and Norway and Iceland compromises completely detached from any MMT economic papers I’ve ever read. It will be the common weal / Richard Murphy lens not the MMT one. A missed opportunity as an independent Scotland could start with a clean slate.

I am still waiting to hear what MMT Scotland and Richard Murphy are going to do with less than 3% deficits at the heart of Europe. Paint the Firth of Forth railway bridge another 100 times.

How they are going to explain to Scottish households and businesses after their savings have vanished and it is all their fault. True to form the common weal and Richard Murphy will blame someone else.

@Steve_American

Thank you for your crazy thoughts! Here are mine.

Sorry to start with a personal remark, but as you identify yourself as an “American”, then what is your expertise in European economy and politics?

According to your description, the EU should not be able to pass a single regulation. This contradicts the reality. Yes, there is plenty of steam rolling and political bribing between the member states, the EU is far from ideal. But the EU decision making processes run surprisingly smoothly. Things like Brexit are spanners in the works.

Your comment bypasses my main point – the war and peace. Do you realise how serious the Irish border issue is? Brexit already started domestic violence in the Northern Ireland. Only very cynical or ignorant politicians and commentators ignore it. Let us expand the Brexit process and the whole can of worms will open. Try to catch the attention of all the 28 EU members with the idea of 1.1, 2 or 3 coefficients then.

I am not an economist either, I am an architect. But your scenarios 2) and 3) seem to me business schemes for euro speculation. I do not think that it is necessary to eliminate euro either. Why should only dollar be an internationally recognised currency? The issue is the inability of the EU member states to issue currency. Estonia is now a household. Our daddy the Prime Minister goes to Brussels to fetch his yearly allowance and squanders some of it on his way home, figuratively speaking. And he is right to tell his citizens that there is no money left for social services, education, science and culture, that we are in debt. Like all daddies tell in distress.

I think there are three alternative ways to go:

1) to eliminate the Eurozone as you suggest;

2) to allow the EU member states, inside the Eurozone, to issue their own currency;

3) to federalise the EU and to reduce the national sovereignty of the member states to the level of territorial and cultural autonomies.

An attempt to implement 3) will fail in the present situation, this is only a theoretical possibility now.

And last but not least, this all has to serve the purpose of stopping the EU austerity policies.

Having read all the comments, why am I the only one to respond to Bill Mitchell’s main concern, the austerity and the social reform? I do not think that the Modern Monetary Theory is about Brexit which is only a local and temporary thing, but a powerful trigger.

Dear Andri Ksenofontov,

In my opinion the main problem facing the EU is that the decision making process is effectively dysfunctional from the point of view of the so-called majority of people inhabiting the area. I used to believe in a so-called “liberal democracy” in the late 1980s when I was a student activist in People’s Republic of whatever. Unfortunately I have very good memory and remember who promised what and what happened next.

As a software engineer I can strongly assert the following – what you see in the EU and elsewhere is a feature, not a bug.

If we don’t re-read Marx we will never understand what is going on. I studied this stuff as a teenager because I hated it, to perfect the art of arguing against so-callled “communists”. Now it comes really handy when I can look at the turning wheels of history through the lens of the class struggle. I would also argue that the only way to understand the price formation process is by applying Labour Theory of Value with the later neo-Ricardian additions coming from Sraffa.

Now we can see why the German oligarchy with the little help of some of the locals has screwed up Greece (and other Southern European countries). And they will never let them go. Yes there is a class struggle going on and as Warren Buffet admitted, the rich are winning.

What happened in the Balitc Republics after the break up of the Soviet Union? They entered a Faustian bargain. To hand over their real assets in return for a delusion of being defended against Russia by the new owners of fixed capital who now have a skin in the game. But Russia is too weak to pounce. There is not much to defend against.

From Santander Trade Portal “According to figures from OECD, most of the FDI stock is concentrated in the financial and insurance activities (28.6%), real estate (17.7%) and manufacturing (13.1%) sectors. The main investing countries are Sweden (27.7%), Finland (22.3%), the Netherlands (7.7%) and Lithuania (4.5%). As with other small-scale open economies, Estonia requires a constant flow of foreign investment in order to maintain its economic expansion.”

This is precisely what the EU is about. But if we go back to Marx, we know that who owns capital can pump out surplus value. So far the bargain kind-of worked but not for the reason we think. Estonia (also Latvia and Lithuania) are developing at a much faster pace than Russia. Why? In my opinion, because of the absolutely incorrect neoliberal macroeconomic policy of Russia. Should they followed the Chinese path to reforming “real socialism”, things would have looked totally differently. (Please have a look at the superb book “From Marx to the Market: Socialism in Search of an Economic System” by Brus and Łaski, from the market efficiency point of view it does not matter who owns the capital). The poison injected during the Destroyka and Yeltsin’s Second Great Smuta eras is still there. But there are other reasons, too. Mainly historical.

Let me get back to the main issue, is it possible to dismantle the Eurozone? We can probably ask Gorbachev about how to organise a perestroyka in the EU. He knew how to democratically dismantle things. They are still in the dismantled state 30 years later. So let’s forget about the so-called “democracy”. “The oppressed are allowed once every few years to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class shall represent and repress them in parliament!” (attributed to V. I. Lenin). This is not how things are done in politics.

We need to look at other countries in Eastern Europe. In Poland, the ruling right-wing oligarchy is actually doing what the so-called leftist have long dreamed about. In the name of the medieval religion as the backbone of the social life and for all the wrong reasons.

They don’t say much but they have refused joining the Euro, started re-nationalisation of the banking system, introduced a massive income redistribution program and (now, before the elections) want to increase minimum wages (often paid to migrant Ukrainian workers as the Poles left for the UK in the previous act of this tragicomedy).

The Germans started whinging about the destruction of democracy but they cannot remove the PiS from power because lower socioeconomic groups offer them solid support. And because the rate of GDP growth in Poland is really high. What is hardly surprising if we acknowledge that in capitalism the system is demand not supply side constrained. Income redistribution from low-marginal-spending-propensity to high-marginal-spending propensity groups works miracles. A few people had been students of Michał Kalecki have invisible influence over macroeconomic policy. (One is actually visible as the member of the Monetary Policy Council)

I am not a supporter of the PiS political movement because it is bordering on fascism. But we have to admit that they do not fail to deliver, unlike the so-called liberal democrats. Unfortunately it was the lack of democracy in China what saved them from the destroyka in 1989.

It is almost like in the Vietnam war. “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.” Nowadays the liberal democracy is not a solution, it is a problem. When my Chinese work mate told me 10 years ago that they had had better democracy in Mainland China, I instinctively recoiled. But maybe he was right when we look at the fate of the workers and ordinary people here and there…

Look I have no answers, only more questions. I am not a supporter of Jarosław Kaczyński or Chairman Xi. All I know is that liberalism is bs. Whether we can have a New Green Deal or fix the Eurozone I am very pessimistic. Maybe the West will start reforming when they lose to China. This is my only hope…

@Andri Ksenofontov,

You want me to reply to your thoughts on wars breaking out in Europe.

As a student of military history I have a lot of knowledge of the history of wars. As an American I have no expert knowledge about the details of the current culture in Europe. However, I don’t fear wars in Europe, because —

1] Who has benefited from starting a war since 1850; yes, 1850? Since 1850 the nation who started a war almost always lost it. It has been worse since 2000. So, what national leader would go against this trend to start an unnecessary war?

2] Since 1945 the world has had “The Nuclear Pax {peace}”. Two nations in Europe have nuclear weapons and will use them to avoid being destroyed. The US frowns on nations that invade their neighbors. Wars are bad for business unless the business is an arms maker. Germany can’t sell its cars into either nation that is at war.

3] It is very much in the interest of the larger nations as a group to make sure that no nation starts a war and benefits from it. It is so nice to have the “General Peace” [whatever its cause is] that the larger nations should not let the idea get going that invading your neighbors to steal their stuff is a winning plan.

4] Yes, many think that the US invaded Iraq in 2003 to steal its oil. But, that didn’t work out so well, did it? It is my non-expert opinion that buying the oil would have cost less than trying to steal it.

5] WWI and WWII demonstrated that modern wars consume ammo and ammo like weapons {tanks, planes, etc} so fast that it is not possible to steal enough after you win to repay the bills you ran it during the war. This is totally different from war before 1800. Then wars didn’t consume stuff for the most part. Mostly the stuff was laying around in good shape on the battlefield after the battle was over.

. . . Also, Iraq shows us another problem with wars to steal stuff in modern times. This is that the IED is cheap and makes it hard to occupy a nation after you win the battles of the invasion. If the occupying nation goes to mass executions to put down the resistance that is using the IED then that looks like war crimes and likely will result in the US coming to set things “right”. Or so it seems to me.

So, I conclude that going to war in Europe is a dumb idea and that the leaders of all the nations know that. So, this is just brought up to scare you with a threat that is impossible to actually see happen. Feel free to show me how I’m wrong about this.

I wrote, “The US frowns on nations that invade their neighbors.”

This should have said, ‘UN’, not ‘US’.

PS —- this ‘don’t start wars’ thing is sort of like the current world opinion on shooting down civilian airliners.

The rich a powerful fly in them and they don’t like to see them being shot down for one obvious reason.

Dear Steve_American and Andri Ksenofonto

Thanks for your comments.

But we are getting way off topic and I don’t want a discussion about military matters on this blog.

We are discussing Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) here and the implications of that sort of understanding.

best wishes

bill

@Ksenofontov

We’ve over this many times, that’s why. Diem had a very modest proposal that is getting nowhere, we’ve been waiting for a Eurozone reform for almost decades and nothing. All we’ve got is a reentrenchment of stereotypes against other nations.

I was casually watching an economics TV show as I was working, but I couldn’t help but start to notice that they (mainstream economists) had all these complaints about Bank fees, negative rates, the difficulty of using hard cash, how the troika money went to save the banks and so on. What did they attribute it to? The local government, of course, with some leftover for the local central bank, none of which can legally do anything about it. I’m sure it’s the same everywhere else, no “serious” economist blames anything but its country.

It’s always funny watching capitalists figuring out the effects of capitalism, but, in the end, they still learn fuck all, because after that they switched to discussing how bad communications providers rip you off, and how electricity is so expensive. The fact that it might have something to do with the forced privatization and deregulation will never cross their minds.

Poverty is peace, greed is freedom, long live the EU.

Bill. I’m sorry.

He brought it up, I ignored it, he called me out for ignoring it and asked me to respond to that, I did respond.

You have every right to want to focus on the economics.

Have a good day.

If anyone wants to pursue the risk of war argument, let me know a different place we can talk.

In a related issue (well its British anyway)

A report commissioned by UK labour has advised against a French-style cap on the working week but has recommended the adoption of a jobs guarantee.

https://www.theguardian.com/money/2019/sep/12/french-style-cap-on-working-week-in-britain-unrealistic-finds-study

@bill and @Steve_American

Sorry for leading the conversation astray from the MMT, but this was exactly my main concern. Whenever “Brexit” is mentioned”, “the Irish backstop” follows, these are two particularities connected with an umbilical cord. Together, these two issues are a distraction from everything else urgent in Europe, including the economic concerns.

I thank Steve_American for the bullet pointed list of the reasons why an outright outbreak of conventional war in Europe is not likely. But the war in Ireland, for example, has never fitted that pattern. And it already started again this year, because of Brexit. I think that this kind of details cannot be missed in a macroeconomic discussion.

@Steve_American, if you have time and you are willing, I am happy to answer you in more detail in some other place, just name it. But I did answer your ideas on fiscal policy. I think this is a good place to discuss them.

@bill, I and Steve_American suggested some possible reform scenarios in the EU. If an expert like you agrees and has time to enlighten beginners in economy like me, I would be very interested to hear any qualified comment.

@Paulo Marques

Thank you for your comment!

I am sure the urgent issues of economy get discussed in a blog of an economist, this also fits the profile of Bill Mitchell. But reporting on austerity in media is superficial and seeking sensation, not understanding. If I wish to find out what is actually going on in the EU economy, where should I look? I see a major problem in how scarcely contemporary social and economic discussion (at least in the media available to me) is supported by actual empirical data. I discovered the MMT material this year as a pleasant exception.

I can say that the mainstream view in Estonian government and among social scientists is that the Tax Office data and bank transfer records are enough for modelling contemporary economics and thanks to the digital information flows there is even too much information. But these information flows and floods hardly explain why I see no farmers selling their veggies at our markets, only middle men and women for a higher price than in supermarkets. Paradoxically, in food market I see less free market now than in the Soviet era (I was born in the 1960s).

@Adam K

I read your long comment with great interest, thank you. I am glad to see you are trying to grasp what is actually going on in the world and I mostly agree with you. And you do not need to worry about my social partisanship. I have my political affiliations like all we do but they do not get into the way of my cognitive interests. Likewise I am happy to discuss bridge building with any engineer, a “commie” or a “nazi”, as long as they can build bridges.

I find Poland a very interesting case in the EU too. All European issues are vast because of the far reaching historical connections, Poland is no exception. You depicted Russia as “just weak”, if you allow me to paraphrase you in such a way. I find it not very precise. In all the ex-Soviet bloc countries large part of economy is a shadow economy based on old power structures. The economy of contemporary Russia is still supervised by the government. The total of the Russian power is less than the total of the Western European power, but practically all this power is concentrated in one fist which pummels hardest if it wills. I find the present formation mostly defensive in character, with the purpose to survive in the contemporary global politics. As the politics turned out to be, not like Gorbachev and his perestroika team envisioned. I am less familiar with what is going on in China.

I am far from being prejudiced towards different countries on base of the degree of government involvement in economic production. It was a very interesting case how the Estonian government, then an independent free market country, solved the economic crisis of 1930s. There were some similarities with the American WW II New Deal. Principally, limitless variations of social structures can work productively.

Creating the Eurozone was a reform. When a reform is possible, then a counter reform is equally possible. But because of Brexit nobody can say anything critical about the EU at this moment, you will be very likely brandished as a stupid brexiteer.

I agree that Marxist studies should continue. For me any empirical social study is Marxist, in a way. Marx was not so smart because he read Marx, but he was the first to implement the methods of hard sciences in comprehensive social research, as I see it. In other words, he started the contemporary empirical social science as we know it. Facts told him what to think. I think that your Marxist analysis matches the facts we both know.

@Andri Ksenofontov,

I suggest we go to ” politicsforum,org “. Replace the ‘,’ with a ‘.’ and if necessary maybe google it.

Say the word and I’ll start a thread for us to argue in.

Dear Andri Ksenofontov,

I am not questioning your description of the processed occurring in Russia (I have not visited that country since I moved to Australia and I only have a few Russian friends here). What I would are explanations based on my understanding of macroeconomics and finance.

A very specific form of corruption is an issue in Russia, not the fact that one may give a bribe to a policeman to avoid a speeding ticket or has to give an envelope to a surgeon at a hospital. It is related to capital flight, the fact that the so-called middle and upper classes have a tendency to store their (often illegally acquired) wealth overseas. The amount is staggering. USD750 billion since 1994 (according to Bloomberg). This could be fixed in the same way it was addressed recently in China but there would be side effects.

But there is another issue, making any meaningful changes practically impossible. Alexei Kudrin and people from his circle, including his successors, believe in neoclassical economics. The word “believe” has a very special meaning in the Eastern European culture. The way people think there is extremely dogmatic, “idealistic”. It could be a result of the importance of Plato in Orthodox Christianity and the virtual absence of Aristotle, whose philosophy was re-introduced to Western culture by St Thomas. Or it may have been caused be something else, the repeated purges and persecution of people who dared to have slightly different views, which started with Ivan the Terrible and his “oprichnina”. The way communism was implemented in the Soviet Union in the late 1920s after the end of NEP (Stalin started by murdering dissenters, what included economists) ensured that the so-called Marxism-Leninism was a fossillised ideology treated like a religion. People (from the Gorbachov’s circle) who discovered that the command system was no longer working when terror was removed after 1956, could only have replaced one dogma with another dogma. (source: I have asked a former Polish minister and he confirmed that). Marxists-Leninists converted to Western economic liberalism. They started chanting slogans from Milton Friedman’s toxic writings in the same way they used to recite from “Short Course on the History of the VKP(b) “.

So if “it is standing written” (стоит написано) that the government must acquire pre-existing money from the non-government sector before it can spend it (what is stated in the so-called loanable funds theory), then it has to be like this. If you do something else, the sky will fall. This was “validated” during the financial crisis of 1998.

You have used the term “empirical social study”. This methodology is exactly opposite to the idealism disguised as the Stalinist version of “dialectical materialism” what morphed onto a blind embrace of the intellectual garbage called neoclassical economics.

Vladimir Putin and his advisers are still behaving like zombies cursed by the shamans of the neoliberal voodoo. How else can we explain that the Russian government has been selling USD-denominated bonds in order to “finance” its spending? A country which at least nominally runs persistent trade surpluses?

The doctrine of Sound Finance is precisely the curse. I am not questioning that Russia may be a military superpower. But looking at the potential of the country, the meagre GDP growth rate suggests that something is totally wrong at the heart. The Russian government (not the Americans) is still applying sanctions to its own society in the form of a semi-persistent austerity.

The Russian ruling circles are well aware that the country has already became a junior partner to China. They have started researching these issues but until the dogma of economic liberalism is ditched, no progress is possible. (one may ask – what liberalism? the country still hasn’t fully reformed and the society is corrupt. I am claiming that this makes them only more vulnerable to insane free market policies such as linear taxation)

Why there is a stagnation? Because of the reasons explained by Bill in the main blog article. Productivity growth is low if the economy is running at the low level of capacity utilisation and without the appropriate level of government spending on R&D, not only on upgrading Soviet-era weapons. This can be partially masked by a relatively low unemployment rate. But this is a result of running a quasi-Job Guarantee in the form of preserving old companies so that people living outside main cities have some sources of income (this can be seen even better in Belarus).

There are many more issues and these are interlinked. If they stimulate the economy now, there will be an increase in capital flight because of the hoarding of money by the rich. (Obviously in the form of foreign currency). Also – because of the high marginal propensity to import. But if the authorities go after the partially corrupt middle class to weed out corruption, there will be nobody left to manage the companies.

Can Russia decisively end the period of the Second Great Smuta? The precondition is ditching the neoclassical economics and starting implementing the same development policies which have been working quite well in China.

Would Vladimir Vladimirovich realise that the neoclassical economics has been promoted by the CIA as an ideological weapon, as a true “fake truth”? Instead of reverting back to the days of glory of Stolypin’s liberal thought they should read Kalecki and do what Deng Xiaoping did in the name of pragmatism.

@Adam K

Your letter is dealing with so many issues of Russian history and politics that responding to it all and trying to fit into the framework of this blog is like trying to keep kitten in a box. If you wish I can send you a more detailed answer by email. I would only like to add that I am not a professional expert in this field but as an architect I have done some research in the urban history of Estonia which was a part of both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. As a student and later I participated in several cultural anthropological expeditions in Russia and did my own research. I also did my compulsory military service in the Red Army and followed the events of the perestroika, then a fresh graduate. This is, more or less, my turf.

I am impressed by your knowledge of Russian history and society, in general you get it right. And there is a lot that can be debated or added.

Many problems of Russia you describe can be reduced to the specifics of the status society in Russia. Historians tend to miss the fact that although dismantled in 1917, the status society bounced back under Stalin’s rule and established its absolute power via the purge of 1934. Although it was not talked about, naturally, the status society was formalised by a series of laws which defined which positions granted the status of the nomenklatura and what were their privileges. I know about these laws from my mother who worked in a historical archive and they had special, not public laws how to process files connected to the members of the nomenklatura. The nomenklatura has always followed the conjuncture, very large part of which has always been adopted from the conjuncture of the “Western” elite. Therefore changing the conjuncture of the Russian elite can be done by the changing of the “Western” conjuncture. But the most straightforward way would be to dismantle the status structure in the Russian society, peacefully or not. Remove the parasite, the princes, from the otherwise able organism. No need to mess with the whole government bureaucracy or the productive managerial staff of the businesses.

About “what to do?”, Gorbatchev tried to model the Soviet economy following the special economic zones experience in China. As he did not see much chance to compete with Vladivostok against the Far East ‘Tigers’ who had already run ahead, he choose to follow the Irish free trade experience instead. Estonia was supposed to become a special economy zone in the Soviet Union with its personnel trained in Ireland. It did not work out because the Soviet Union collapsed. I am telling it to point out that this idea is not unknown to the Russian elite.

According to human geography a successful economy has to fit into the geographic, historical and social conditions where it is embedded. Economic success models are not easily transferrable from place to place on a large scale. The productive way is to start with the geographic, social and economic survey of the area to gather necessary data and then, on base of that data, to make informed economic decisions and shape the policies. Unless economists are busy with testing multiple models based on hard data I do not see much hope for long term sustainable economic progress, whether the country copies somebody’s success models or not.

The government and at least some of the mainstream social scientists in Estonia think that the data of the Tax Office and the bank transfer records are enough to model economic processes. They even think that contemporary digital information flows provide too much data. But I do not see how the digital information flows or floods can explain why I do not see farmers selling their products at the markets themselves, only middle men and women for higher prices than in supermarkets. We still need comprehensive empirical economic research to understand the whole picture and to really move on from there where we really are.

@Adam K

One more little thing: you referred to the main blog article by Bill. I was not able to identify it. Would you give me the link? And thanks for the reference to Kalecki!

@Andri Ksenofontov,

OK Andri, I started a thread in that other forum in “Europe”. You can publicly comment there if you join.

If you want to talk in private, all I can suggest is another forum.

In this case BoardGameGeek. This site lets members send Private Messages to each other.

You could join just only to talk to me.

I have a rule against giving out my email address in a pubic forum site. I’m sure you understand.

@Steve_American

Hi,

politicsforum[dot]org has not answered me yet. Maybe they did not like my email address hectopod[at]yahoo.com. My twitter handle [at]hectopodbug is also connected to it.

@Andri Ksenofontov,

I tried to send you an email and it was returned right away with an error message that “this user doesn’t have a yahoo account. Maybe try to join Politicsforum again or BoardGameGeek.

But, my reply to which I ask you to avoid replying to is — consider the number of lives lost or ruined per year in a new round of Troubles and the number of lives lost or ruined in either the UK only or all of the EU and UK. If my estimate is right then austerity is killing far more people in UK only than the Troubles will, per year.

.

Sorry Bill. I promise to leave it there here and go elsewhere with this.

@Steve_American

Sorry, it was my mistake. This email address of mine has a different extension which I tend to forget:

hectopod[at]yahoo[dot]co[dot]uk. I keep it for creating various accounts and I am receiving there all my Facebook notifications etc. My general correspondence goes via andriksenofontov[at]yahoo[dot]com. Choose which you like.

PS Some macroeconomic notions: not every social phenomenon is quantifiable. And things that are difficult to quantify give different results using different criteria or modelling systems. Sometimes it is a matter of error and precision, sometimes the subject matter itself is inherently paradoxical. We are human beings, after all.