Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

There are no financial risks involved in increased British government spending

On July 26, 2018, UK Guardian columnist Phillip Inman published an article – Household debt in UK ‘worse than at any time on record’ – which reported on the latest figures at the time from the Office of National Statistics (ONS). He noted that the data showed that “British households spent around £900 more on average than they received in income during 2017, pushing their finances into deficit for the first time since the credit boom of the 1980s … The figures pose a challenge to the government … Britain’s consumer credit bubble of more than £200bn was unsustainable. A dramatic rise in debt-fuelled spending since 2016” and more. While keen to tell the readers that British households were “living beyond their means”, there was not a single mention of the fiscal austerity drive being pursued by the British government over the same period. Nor was there mention of the fact that the entire British fiscal strategy since the Tories took office was predicated, as I pointed out years ago in this blog post – I don’t wanna know one thing about evil (April 29, 2011), on this debt binge continuing. A year later (July 20, 2019), the same columnist published this article – Labour and Tories both plan to borrow and spend. Is that wise? – which like its predecessor fails to present a comprehensive, linked-up, analysis for his readers and makes basis macroeconomic errors along the way.

The latest article is attacking both the variously announced intentions of the British Labour Party and the Tory government to increase net public spending.

On October 29, 2018, the British Chancellor, sensing the deepening unpopularity of the Tory government, promised in his – Budget Speech that:

… the era of austerity finally coming to an end.

He said it was time (he was talking about the “Deal Dividend” that never got off the ground because there was no ‘Deal’) that he set about giving the economy:

… a boost from releasing some of the fiscal headroom that I am holding in reserve at the moment.

It was all nonsense talk designed to give the impression that the Brexit process was under control and in train and that he finally had the ‘fiscal space’ to ensure the negative consequences would be minimised.

His concept of ‘fiscal space’ – that it increased the smaller the deficit or the larger the surplus – was erroneous of course. It was a denial of the most basic currency capacity that the UK government possesses – it can never run out of spending capacity.

Which, of course, is not the same thing as saying that it can run out of things to spend on.

He was also dealing with a Labour Party that was intent on taking government and implementing a wide-ranging infrastructure plan, some of the more important aspects would not be possible while it remained with the EU, but they seem to be in denial of that fact.

It is clear that the Labour Party intends to break with the austerity mindset that has damaged prosperity in Britain for at least the last decade.

Whether it will or can is an open question and as I have indicated in the past – its adherence to a neoliberal fiscal credibility rule – is likely to cause it grief if it is confronted with a significant downturn in non-government spending.

The latest Tory shenanigans have left the likes of Philip Hammond behind. He is now yesterday’s man and on borrowed time as they say.

The new British PM will be announced next week – a most curious process – and it is likely to be Boris Johnson – a man most unsuited to the job.

He joins a long list – May, Cameron, Brown, Blair, Major, Thatcher, Callaghan etc – all of whom it could be said were unsuited for the job for various and different reasons.

But, Johnson (and his co-candidate Hunt) have both promised to introduce significant fiscal stimulus packages designed to redress some of the obvious damage that the austerity has generated but also to insulate the British economy from its impending October 31, 2019 exit from neoliberal central – the European Union.

I actually agree with Boris Johnson that Britain can avoid recession if the government acts sensibly in relation to fiscal policy. Whether the government will be capable of acting sensibly is another matter – but they have the capacity to avoid recession.

The latest analysis from the Office of Budget Responsibility – Overview of the July 2019 Fiscal risks report (July 18, 2019) – is breathtakingly biased towards the conclusion it seeks to reach – that a No-Deal Brexit would force Britain into a deep recession.

Its use of the IMF stress test framework leads it to conclusions as bad as the IMF is famous for delivering.

What they hold constant – is the very thing that has the capacity to avoid the recession.

And while acknowledging that the economy is entering a highly uncertain period and that economic growth has “paused at best in thee second quarter” and that a “more general weakness may persist and intensify as 31 October nears”, it still claimed:

But policy risks to the public finances in the medium term are significant and look greater than they were two years ago. In his recent statements the current Chancellor has all but abandoned the Government’s legislated objective to balance the budget by the mid-2020s. And the £27 billion a year NHS settlement announced in June 2018 – unfunded, unaccompanied by detailed plans for reform and outside the normal timetable for spending decisions – has cast doubts over the Treasury’s usually firm grip on departmental spending.

So with the British economy apparently close to recession already and households carrying record and unsustainable debt burdens, the OBR, which is meant to give ‘independent’ advice to the government on fiscal matters, wants the austerity to continue.

And this is the backdrop on which Phillip Inman penned his latest piece (cited above).

In the context of these prospective public spending increases (whoever is in government), Phillip Inman claims that:

Britons, then, find themselves for the first time since the financial crisis in a similar situation to Italians in their last general election, with parties at both ends of the political spectrum wanting to spend large amounts of mostly borrowed money to spur investment.

First check on any Op Ed: does it conflate currency issuers with currency users?

If so, you can ignore what they write.

Italy uses a foreign currency – the euro.

Britain issues its own currency – the pound.

Italy has to – by dint of being in the Eurozone – issue debt denominated in a foreign currency to raise the funds to cover its fiscal deficits.

Britain does not have to issue debt at all if it chooses and never has to issue debt in a foreign currency.

There is no meaningful comparison between the two nations in terms of financial constraints arising from spending promises.

Why Phillip Inman misses that basic point is unknown but telling.

He then says that the spending promises are in fact promises to pursue “a huge increase in government borrowing”.

In the current institutional practice, the government is likely to maintain the unnecessary link between deficit spending and borrowing, although clearly there are voices mounting to break with that neoliberal tradition and instead use the currency capacity of the Bank of England to spend without the debt matching.

Clearly, the British government can run deficits without having to match them with debt issuance, although they would get huge push-back from the financial markets who cannot get enough of British government debt – after all, it is a form of corporate welfare payment.

He claims that “for money over many decades”, the “borrowers to dictate what they pay for loans” – and that is “not much”, given the likelihood of continued “almost zero” interest rates (and yields).

And while he differentiates between Labour’s “slow-burn solution” (infrastructure spending in neglected areas) from the Tory plan to give tax cuts” he still claims that:

Only an ideologue could fail to see that both routes out of the current torpor are fraught with risks. Labour may find that, following decades of neglect, pouring financial fertiliser on the regions has little effect. And businesses that have rejected commercial bank funding to support investment plans may give a state bank the same two-fingered salute.

The Tory solution has even less chance of success. We know this after nine years of cuts to corporate taxes, which have done nothing to spur investment.

So what is the risk here?

The article starts off railing against the prospect of higher public spending and the debt increases that probably would accompany that spending.

But then its big conclusion on risks is that such a strategy may not actually be stimulative.

It is thus unclear what the problem his article is addressing.

Is it too much debt or too little growth?

And what is the use of the term “ideologue” denoting here? Obviously pejorative.

But basic macroeconomics tells us that one sector’s spending is another sector’s income.

If the Labour government was to revitalise public transport, for example, throughout the regional areas – and hired construction workers, new manufacturing contracts, new staff to person the services, and more – why would that have “little effect”?

Apparently, the public spending multiplier according to Inman (implied) is close to zero.

But I would guarantee that if the government announced some large projects that local regions where the spending was actually going would achieve higher incomes.

Why is that insight “only” for “an ideologue” to have?

Ridiculous.

Perhaps, also that British households might decide to save more of the increased disposable income and render their balance sheets, currently in a precarious state from the record levels of unsustainable (in Inman’s 2018 assessment) debt, a little less risky.

This would also likely be the result of a personal tax cut, although it would depend on the targetting.

The point is: Why hasn’t he made the connection between the unsustainable household debt and the fiscal conduct?

I guess it is whatever sounds like a good story on the day he has to file and who cares about continuity or logical linkages between the topics.

Perhaps he doesn’t actually understand the link between the sectors?

That appears to be a correct assessment when we read:

With austerity measures in place, total UK public debt is expected to decline over the next five years from 80% of GDP to around 70%. Reverse that trend and the government starts to match the profligacy of households and corporates that have sent private debt spiralling to 250% of GDP and beyond.

We know that the fiscal deficit has contracted because tax revenues have grown on the back of economic growth.

What has been driving that growth?

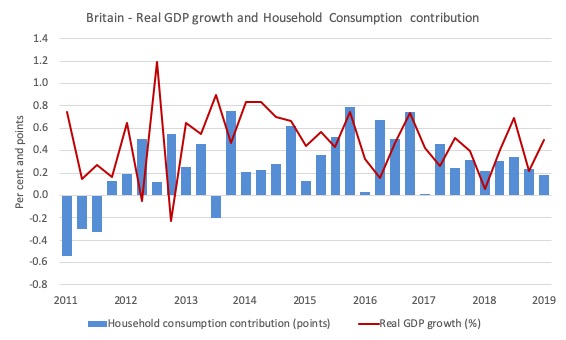

The following graph tells you the answer.

1. Net exports have been consistently dragging down growth.

2. Private investment has been making a negative or minimal contribution over the period shown.

3. Household consumption has dominated although that contribution is in decline over the last few quarters.

So if the British households, for example, had not borrowed so much, real GDP growth would have been significantly lower than it has been and tax revenue collected much lower.

The reduced fiscal deficits have come directly from the excessive use of private credit. And as I indicated in my blog post cited above, that was a deliberate strategy of the Tory government – to increase the risk of the private sector while claiming they were ‘fixing’ the fiscal situation.

While it makes sense to talk about a deteriorating private domestic finances, there is no meaning to that concept when applied to the finances of the national, currency-issuing government.

But Inman clearly thinks that there is no particular relationship between the two sectoral balances. A major mistake made by many mainstream analysts.

We learn more on how astray his analysis is when he extrapolates with this:

It may seem defeatist to say so, but if you are concerned about another financial crisis, or even a plain vanilla recession, higher borrowing puts finances at risk.

At which point you know his ‘risk’ worries relate to solvency issues rather than the size of the spending multipliers.

And at the same point you realise this sort of analysis is nonsensical.

What is the risk of higher public debt?

1. Solvency? The British government can always meet the requirements of any outstanding liabilities issued in sterling.

2. Yields? Inman has already concluded that yields will be low “over many decades” to come.

3. Fiscal space? A higher fiscal deficit now places no financial limitations on the capacity of the British government to run whatever deficit is required tomorrow or the next day to meets its objectives.

It is true that a higher deficit now, may reduce the available real resources that can be brought back into productive use – which means the government is pushing the economy closer to full capacity, which in anyone’s language is a positive move as long as environmental sustainability is being pursued.

But that just means there is a real constraint on government spending. There is no sense that “finances” are “at risk”.

Risk of what? Stupid talk.

Equally stupid is his claim that:

… the UK’s public finances are already worsening, it might be better to hunker down.

Hunker down how?

Imposing more austerity?

Causing people to lose their jobs?

Promoting low wages growth?

What the F**k!

Conclusion

A sorry story for UK Guardian readers to have to engage with.

The problem is that most readers are bluffed by this type of spurious analysis.

Come the day that an Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) understanding is widespread – we are working on it – the likes of Philip Inman will have to do something productive to earn a living.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’m afraid I tend to bypass Inman’s columns these days. I would have read them in the past but since reading this and other MMT focused blogs I’ve learned to dismiss them for what they are. The Guardian has drifted inexorably to the right since Viner took over as editor and virtually all their columnists trot out a neoliberal line even when condemning neoliberalism and austerity. I think even Edward Heath’s government would be too left wing for the British Media and the BBC. Corbyn is off the scale and on Saturday Vince Cable was extolling Liberal Conservative coalition as essential to avoid a Corbyn led government. HELP!

‘I actually agree with Boris Johnson ‘

And this is highly ironic! Of course, Johnson burbling about ‘fiscal headroom’ is still perpetuating myths (about which he himself might have little or no understanding) that we’ve ‘suddenly’ found assets behind the sofa. It’s all part of the con.

Johnson is playing the usual trick of neo-libs: keep pushing the austerity and wealth siphoning until the natives get restive BUT then only only deliver a few crumbs from the table until all is settled and then push the rentier, austerity activity again.

Off course, with the Brexit crowd chanting ‘take back control’ (off what and how is never really stated) and the Remain camp chanting ‘remain and reform’ (of what and how is never stated) there is massive cognitive dissonance to be exploited-another gift to the neo-libs. A confused and benighted public = trebles all round at neo-Lib Central!

“It is thus unclear what the problem his article is addressing.”

Touché!

Although your efforts in parsing the article are worthy and appreciated, Philip Inman is simply not worth reading – and the same can be said for 98% of the Guardian’s output.

It should be re-named “The Handwringer”, because that’s all it does.

Solutions are never on offer, or if they are, they depend on individual consumer choices, or some vague notions of localism.

It’s only worth headline-skimming to see if there’s been a natural disaster somewhere – or whether or not your team has won a sports event, if that’s what you’re into.

Although it was certainly never radical, it has morphed in the past few years into a bizarre hybrid of Cosmopolitan magazine, and the house journal of the security services: ceaseless snowflake virtue signaling, set alongside hardcore NATO propaganda.

It’s just weird these days.

….and they’re incessantly begging for money, which, were they on a street corner, would see them moved on, or arrested for vagrancy!

#dumptheguardian

The UK Guardian is a faux-progressive piece of shit written and run by sanctimonious morons. It’s unfortunate that their increasingly click-bate based business model has apparently saved them from bankruptcy.

Bill,

The OBR & ONS both have a poor record in forecasting any economic parameters so taking the opposite view would give a better guide!

Mr Shigemitsu,

“The Handwringer” is exactly correct. It’s a solutions-free rag for the schadenfreude loving middle-classes who mistakenly think they’ll be alright if everything remains the same but with everyone acting a bit more polite and PC.

Reality is if they don’t wise-up they’ll soon be just as fucked as the working classes and minority groups they oh so extravagently and oh so publicly pretend to give a shit about.

#dumptheguardian

I was a bit disappointed to read the other day Larry Elliott writing about the “deterioration” in public finances (because the deficit for June is twice as big as it was in June 2018). To be fair, he was talking about the recent OBR report, and using their language I suppose, but even so, he should (and I believe does) know better. He could have put in some corrective points from an MMT perspective for the Guardianista latté-drinkers.

Well, for those who need an antidote to The Guardian, there is always Off-Guardian. (I will leave people to find it with their search-engine of choice).

Does this writer have a point: ? He is a B.Ec. (Hons) claiming “while I more or less agree that MMT is theoretically sound (especially the way that national debt works in a monetary sovereign nation), he continues:

<>

“MMT in secret”: (I love it!….. but is this the only way…..)

He is a staff member in the electorate office of an ALP senator.

While his concerns about “a speculative frenzy” and “devaluation” might be misconstrued, nevertheless given the general ignorance re macroeconomic reality among central bankers from the IMF down, does his conclusion have force? Is this why some people believe MMT must be understood by the US Fed *before* other countries can ‘dare’ follow MMT revelations – which after all would make every country of earth more prosperous – about which the Pentagon might have some views?

Fact: we don’t have an effective international rules based system. Can anyone see the way through this maze?

Here is the missing text in my previous post:

For example (this is also another one of my criticisms of MMT), MMT theorists have no idea about how other nations might react to an Australian Government pursuing macroeconomic policy in-line with MMT . Australia is a small, open economy that has a large portion of its economy reliant on international trade and international financial markets (our dollar being on the foreign exchange and our bonds being available for purchase in international bond markets). If other nations that were more economically conservative (or even just hedge funds and investment banks that trade our dollar) were to catch wind of Australia’s new macroeconomic policy direction and had concerns about Australia’s dollar devaluing, it might cause a speculative frenzy which could crush our currency and subsequently our economy. It almost ends up being a Game Theory type situation between countries. If one were to pursue these policies, they don’t know if they will be punished or not by other countries and financial markets. The payoff being large but the consequences also being large. If you think of it from this perspective, it makes sense that policy makers play it safe and don’t pursue MMT macroeconomic policies as they don’t want to risk pushing the nation to the brink from a speculative frenzy on our currency and a refusal to buy our bonds. It might be the case that governments talk a big game about a ‘balanced budget’ but then pursue MMT in secret. However, this would still be subject to significant risk if other countries were to catch on.

so same as Greece?

Commitment is a commitment. Back into the weak economy you go!

“First check on any Op Ed: does it conflate currency issuers with currency users? If so, you can ignore what they write.” Here Bill gives us another gem: an elementary and highly useful rule of thumb; an excellent example of intellectual efficiency. Those of us who “evangelize” for MMT should accordingly direct the lion’s share of our energy to undermining the household budget paradigm, drilled into the public mind as the context in which to consider (currency-sovereign) federal spending. This threshold issue is not a divisive political one of right and left but rather a unifying factual issue of right and wrong. In this regard, the most effective breakthrough presentation I’ve found, the one that has “converted’ many of my friends, is Stephanie Kelton’s “Angry Birds” YouTube video. Once people free themselves from household budget conditioning, then Bill’s blog and books become incredibly rich resources to dive more deeply into macroeconomics if they’re so inclined. Indeed, “Reclaiming the State” remains IMHO the most important book out there right now. But has anyone found an initial MMT “conversion pitch” as good (or even better) than the entertaining “Angry Birds” video? If so, I’d love to know about it. “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few,” so we “evangelists” need the most effective resources available to spread the MMT “gospel” to the masses and allow the truth to set them free. I trust my secular friends will take my “religious” language in the metaphorical and inclusive spirit intended.

“Labour and Tories both plan to borrow and spend. Is that wise? ”

This was the worst, most ridiculous article I have read in the Guardian and I pointed that out in a BTL where I made it clear the British government issues the pound and can buy anything that is on sale (including unemployed and underemployed labor) in pounds.

I was jumped on immediately by the Guardian’s British readership!

The words Venezuela and Zimbabwe were used.

I don’t think the British (who let’s be honest started this neoliberal rubbish when they lost their nerve in the 1970s) are ready for a dose of common sense.

“It might be the case that governments talk a big game about a ‘balanced budget’ but then pursue MMT in secret”

You have more reading to do.

@ Allan

Tuesday, July 23, 2019 at 12:04

” “It might be the case that governments talk a big game about a ‘balanced budget’ but then pursue MMT in secret”

You have more reading to do.”

Is this not what every Repud President since Reagan and the Repubs and Repuds in Congress have done since then too? {Except maybe Bush I. And he lost his reelection bid for raising taxes to have “sound finance”.}

They talk about balancing the budget and borrow and spend whenever there is a Repud in the White House.

Repuds in Congress only keep the US Gov. from spending or cutting taxes {weighted toward the rich and the corps. they own} when the Pres. is a Democrat. It is their Santa Claus strategy. It is to give *some* nice stuff to the voters while not letting the Dems do the same, coupled with giving a *lot* of nice stuff to those in America who don’t need it and can’t spend it because they already have everything they might want to buy.

Bush II gave us a tax cut, Medicare part D {covering drugs}, and 2 wars without paying for any of the 4. He also started the bailouts in 2008 that spent or loaned {by some FOIA request info based reports I’ve seen} around $27 trillion . Trump gave us more wars and more tax cuts without paying for any of that either.

So, MMT in secret.

.

Neil, I agree with Steve: you have some more reading to do. Australia has to worry about the foreign appetite for govt bonds – nonsense. If foreigners don’t want to acquire and hold Aussies, well guess what, yea the Aussie falls and they lose their export market, at which point their economy starts to collapse, all the while Australia investment and production soar into the void left by foreigners. Sounds like a good thing to me.

I just got this reply from Inman:

“Hi Carol

You will know that I, like many others, have for many years promoted a land tax.

Underlying all my recent articles is that we have lost the ability to tax. The baby boomers generation, in the main, refuse to give up their wealth and income, which is why the political parties are so keen to borrow.

If you think borrowing has no other consequences than a fall in the value of sterling, then were certainly far apart in how we understand the nature of the UK economy and the effect of our existing borrowing should the be a global recession or God forbid another crash.

Best wishes

Phillip”

He obviously has not bothered to read this blog which I recommended.

Has anybody done any research on the potential public attitude to money if MMT went mainstream?

IE they/us actually understood the basics and therefore no longer saw Gov Debt as a negative, but rather the opposite.

A case of game play from the consequences from changing attitudes. This is big picture question with no actual right answer.

Cheers, or put on another page as appropriate, just wanting to find some answers, thoughts etc….

Dear Allan, Steve and Yok:

Please note: the *two* successive posts (above) under my name (Neil Halliday):

the first of these is my own comment, while the 2nd of these posts (to which you have all replied) is the text of a reply I obtained from an economics graduate (who is a staff member in the electorate office of an ALP senator).

(In my first post, the text between the brackets, containing the reply I received from the senator\’s adviser, failed to appear so I resent it separately – in my second post. Sorry for the inconvenience.)

IOW, it is not me who has to do some extra reading, but my correspondent in the senator\’s office.

Btw, Steve makes a good point about the Repubs practising “MMT in secret”…….

For Grant Beerling.

“Has anybody done any research on the potential public attitude to money if MMT went mainstream?”

This is exactly the question my correspondent (a B.Ec Hons.) who is an adviser to an ALP senator in Adelaide, put to me about MMT.

Here is part of the text of his correspondence to me (btw he claims to agree with much MMT analysis especially re sustainability of *government* debt :

“For example (this is also another one of my criticisms of MMT), MMT theorists have no idea about how other nations might react to an Australian Government pursuing macroeconomic policy in-line with MMT . Australia is a small, open economy that has a large portion of its economy reliant on international trade and international financial markets (our dollar being on the foreign exchange and our bonds being available for purchase in international bond markets). If other nations that were more economically conservative (or even just hedge funds and investment banks that trade our dollar) were to catch wind of Australia’s new macroeconomic policy direction and had concerns about Australia’s dollar devaluing, it might cause a speculative frenzy which could crush our currency and subsequently our economy. It almost ends up being a Game Theory type situation between countries. If one were to pursue these policies, they don’t know if they will be punished or not by other countries and financial markets. The payoff being large but the consequences also being large. If you think of it from this perspective, it makes sense that policy makers play it safe and don’t pursue MMT macroeconomic policies as they don’t want to risk pushing the nation to the brink from a speculative frenzy on our currency and a refusal to buy our bonds. It might be the case that governments talk a big game about a ‘balanced budget’ but then pursue MMT in secret. However, this would still be subject to significant risk if other countries were to catch on.”

So… no progress until the boffins at the IMF and all other central bankers down to and including Philip Lowe, understand MMT?

Hello again Grant,

further to your specific remark about research on the “potential (change in) public attitude to money” (if MMT goes mainstream), no surprises that a conservative (Libertarian) forum debater refers to MMT as “counterfeiting” money…..

@ Neil,

I didn’t say anyone needed to do more reading. I just quoted the whole reply and then just replied to the part about using MMT to do what it lets you do *in secret*.

.

As for the Labour Party using MMT in secret, I suggest that many people explain to them the facts of life/economics and then tell them what to tell the voters while the voters still believe the nonsense.

They should explain to the voters that making investments in the future is exactly what a comp. should be borrowing to do. And that for the UK as a whole examples of “investments” are not limited to building & maintaining infrastructure that the economy needs to keep producing stuff that adds to the GDP that adds to tax revenues. In addition to this, there are 2 main areas where spending is really investing in the future; education {incl. buildings and teacher pay, etc. to educate the future workers of the nation}, and healthcare for all {to keep the workers the nation has now healthy and alive so they can work to produce GDP and therefore pay taxes}.

.

So, all new debt that pays for infrastructure, education, and healthcare should not be counted as being “bad debt”, that it is “good debt”. that *ALL* spending for those 3 areas {and maybe more I can’t think of} *must* be taken out of the main budget and out into the “investment”budget, and all of the investment budget paid for with borrowed money. I know it is a crock, but the Labour pols have to tell the voters “something”. The Repuds tell the voters that tax cuts will stimulate the economy and so pay for themselves, this is an example of a “something”. Labour needs a something too.

.

BTW — I saw a report that Rush Limbaugh of Fox News said recently on air that all the talk about deficits will lead to trouble was bullshit from the start in the 70s. That nobody believes that anymore. [My words, his meaning.] Try googling it.

Steve: yes it was Allan and Yok who noted the need for further reading on my part – even though Yok thought he was agreeing with you……my fault for not being able to deliver the senator’s adviser’s reply to me, in my first post! (ah…. the joys and difficulties of communication…)

Steve: interestingly, Bill’s latest blog mentions those very Limbaugh ‘revelations’ .Amazing…

BTW, I like your concept of different ‘types’ of debt (“good” and ” bad”).

As a related example of this, I walked into an Uni Economics department recently, and presented this proposition:

“Some desirable economic activity ‘consumes’ only time and effort (whether physical or mental) eg education (given existing infrastructure) and assisting the elderly to remain in their own homes, which is unlike other economic activity eg producing widgets in a factory which *does* include consumption of real scare resources. One of the professors I mentioned this to seemed quite taken aback, when he realised the mainstream approach to taxation (ie tax first in order to spend)

might be erroneous.