Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – July 6-7, 2019 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Mainstream economists use the notion of “crowding out” to argue that public spending squeezes out private spending and results in a less efficient allocation of resources overall. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) denies that crowding out can occur.

The answer is False.

The normal presentation of the crowding out hypothesis which is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention is more accurately called “financial crowding out”.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory. Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

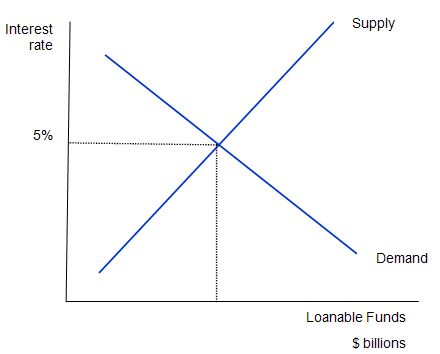

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment. Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that budget surpluses are akin to this. They are not even remotely like private saving. They actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of budget surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to “any other market in the economy” despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates – read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consquences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a budget deficit. Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

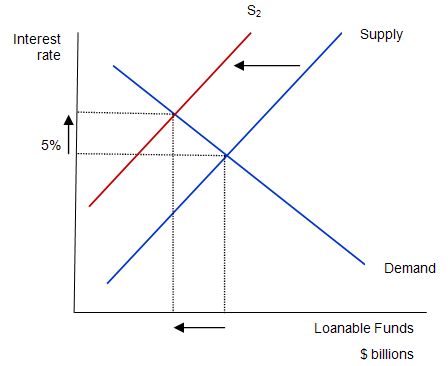

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2. Why does that happen? The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising budget deficit reduces public saving and available national saving. The budget deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Sometimes, this makes is hard to know where to start in debunking it. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no! Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors. Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading “financial crowding out”.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

However, other forms of crowding out are possible. In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

Further, while there is mounting hysteria about the problems the changing demographics will introduce to government budgets all the arguments presented are based upon spurious financial reasoning – that the government will not be able to afford to fund health programs (for example) and that taxes will have to rise to punitive levels to make provision possible but in doing so growth will be damaged.

However, MMT dismisses these “financial” arguments and instead emphasises the possibility of real problems – a lack of productivity growth; a lack of goods and services; environment impingements; etc.

Then the argument can be seen quite differently. The responses the mainstream are proposing (and introducing in some nations) which emphasise budget surpluses (as demonstrations of fiscal discipline) are shown by MMT to actually undermine the real capacity of the economy to address the actual future issues surrounding rising dependency ratios. So by cutting funding to education now or leaving people unemployed or underemployed now, governments reduce the future income generating potential and the likely provision of required goods and services in the future.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues. If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that. It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example). But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

Question 1:

Larger fiscal deficits as a percentage of GDP typically mean that there are less real resources available for other productive uses.

The answer is True.

It is clear that at any point in time, there are finite real resources available for production. New resources can be discovered, produced and the old stock spread better via education and productivity growth. The aim of production is to use these real resources to produce goods and services that people want either via private or public provision.

So by definition any sectoral claim (via spending) on the real resources reduces the availability for other users. There is always an opportunity cost involved in real terms when one component of spending increases relative to another.

Unless you subscribe to the extreme end of mainstream economics which espouses concepts such as 100 per cent crowding out via financial markets and/or Ricardian equivalence consumption effects, you will conclude that rising net public spending as percentage of GDP will add to aggregate demand and as long as the economy can produce more real goods and services in response, this increase in public demand will be met with increased public access to real goods and services.

You might also wonder whether it matters if the economy is already at full capacity. Under these conditions a rising public share of GDP must squeeze real usage by the non-government sector which might also drive inflation as the economy tries to siphon of the incompatible nominal demands on final real output.

You might say that the deficits might rise as a percentage of GDP as a result of a decline in private spending triggering the automatic stabilisers which would suggest many idle resources. That is clearly possible but doesn’t alter the fact that the public claims on the total resources available have risen.

Under these circumstances the opportunity costs involved are very low because of the excess capacity.

The question really seeks to detect whether you have been able to distinguish between the financial crowding out myth that is found in all the mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and concepts of real crowding out.

The normal presentation of the crowding out hypothesis which is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention is more accurately called “financial crowding out”.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

At the heart of this erroneous hypothesis is a flawed viewed of financial markets. The so-called loanable funds market is constructed by the mainstream economists as serving to mediate saving and investment via interest rate variations.

This is pre-Keynesian thinking and was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

So saving (supply of funds) is conceived of as a positive function of the real interest rate because rising rates increase the opportunity cost of current consumption and thus encourage saving. Investment (demand for funds) declines with the interest rate because the costs of funds to invest in (houses, factories, equipment etc) rises.

Changes in the interest rate thus create continuous equilibrium such that aggregate demand always equals aggregate supply and the composition of final demand (between consumption and investment) changes as interest rates adjust.

According to this theory, if there is a rising budget deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending.

So allegedly, when the government borrows to “finance” its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. The mainstream economists conceive of this as the government reducing national saving (by running a budget deficit) and pushing up interest rates which damage private investment.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost self-evident truths. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

Further, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. But government spending by stimulating income also stimulates saving.

The flawed notion of financial crowding out has to be distinguished from other forms of crowding out which are possible. In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues. If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that. It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example). But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

Question 2:

For a nation running a current account deficit, income adjustments will ensure government fiscal position is in deficit if the domestic private sector seeks to increase its saving overall as a percentage of GDP.

The answer is True.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

Refreshing the balances (again) – we know that from an accounting sense, if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

The important point is to understand what behaviour and economic adjustments drive these outcomes.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAB > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAB < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAB] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAB] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

Assume, now that the private domestic sector (households and firms) seeks to increase its saving ratio (as a percentage of GDP). Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income. The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract – output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms’ investment plans – they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public fiscal balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its saving ratio then the contracting income will clearly push the fiscal position into deficit.

So we would have an external deficit, a private domestic surplus and a fiscal deficit.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Off topic.

What can a fiscal Eurozone “Authority” do to let the eurozone take advantage of MMT?

1] It (the Eurozone “Authority” ) would start taxing something. It would impose the rules on Germany and make it pay what it owes for all the years it broke the rules. This is to punish Germany for exporting too much for many years. Just because Germany didn’t voluntarily pay and nobody made it pay isn’t a reason they don’t now owe it. The rules are the rules after all. This would be one “tax”, a “too much exports tax”.

2] It would set up a Job Guarantee program.

3] It would insurer all bank deposits in all the eurozone nations, think FDIC. It may have to regulate the banks.

4] It should buy half of all bonds sold by each nation to deficit spend and lock them away for 500 years. Half is my initial estimate of how much, adjust this up or down equally for all the nations.

5] It would have to guarantee that all national bonds will be paid on time. And find a way to “punish” the Gov. and elite of nations that can’t pay on time for the half of the bonds they have to pay back when they come due. It is, after all, the elite’s fault and not the poor’s fault.

6] It would take over all the national Soc. Sec. retirement programs and guarantee to always pay that bill.

7] It would sell its own bonds to pay for any deficit in its own S.S. program, JG program, FDIC program, etc.

YES, I know it is a *total* waste of time to even think about this program.