Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australian labour market – weak with broad underutilisation rising

Today, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest data – Labour Force, Australia, November 2018 – which shows that the employment growth was all due to part-time jobs growth (probably related to the Xmas season) and both full-time employment and hours worked were negative. Not a good sign. The moderate employment growth, however, trailed behind the growth in the labour force and unemployment rose a bit. The broad measure of labour underutilisation rose by 0.3 points to 13.6 per cent with underemployment rising by 0.2 points. Again, a sign of a weak labour market that is relying on part-time jobs for growth. The Australian labour market remains a considerable distance from full employment. There is clear room for some serious policy expansion at present.

The summary ABS Labour Force (seasonally adjusted) estimates for November 2018 are:

- Employment increased 37,100 (0.3 per cent) – full-time employment decreased 6,400 and part-time employment increased 43,400.

- Unemployment increased 12,500 to 683,100.

- The official unemployment rate increased 0.1 pts to 5.1 per cent.

- The participation rate increased 0.2 pts to 65.7 per cent.

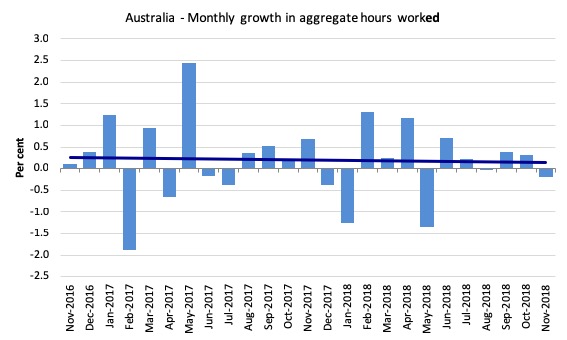

- Aggregate monthly hours worked decreased 3.3 million hours (0.3 per cent).

- The monthly broad underutilisation estimates for November 2018 show that underemployment increased by 0.2 points to 8.9 per cent (1,132 thousand). The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) rose by 0.3 points to 13.6 per cent. There were a total of 1,815.1 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

Employment increased by 37,100 in November 2018

Employment growth was steady this month although full-time employment fell.

Total employment increased 37,100 (0.3 per cent) – full-time employment decreased 6,400 and part-time employment increased 43,400.

The moderate employment growth, however, trailed behind the growth in the labour force (0.4 per cent) and unemployment rose as a consequence, the second consecutive month we have seen this.

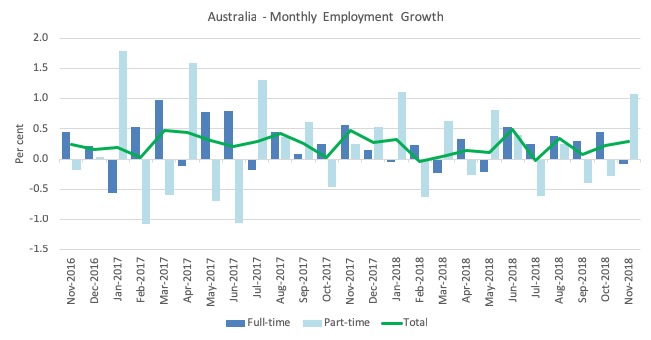

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 24 months to November 2018 using seasonally adjusted data.

The zig-zag pattern where employment growth has regularly been around zero remains evident.

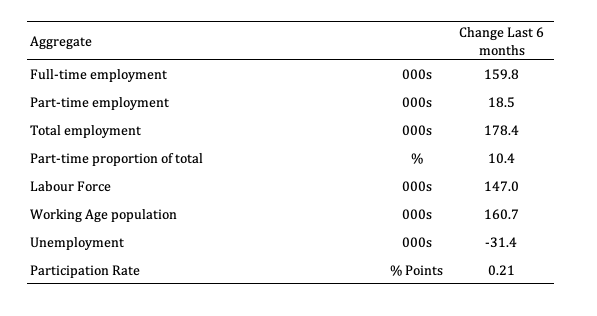

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months. As the monthly data is highly variable, this Table provides a longer view which allows for a better assessment of the trends.

These aggregate changes signify a moderate labour market performance.

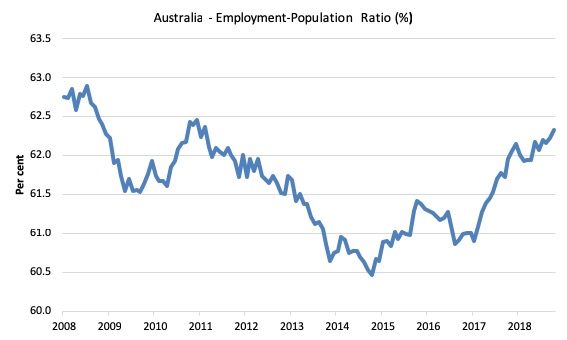

Given the variation in the labour force estimates, it is sometimes useful to examine the Employment-to-Population ratio (%) because the underlying population estimates (denominator) are less cyclical and subject to variation than the labour force estimates. This is an alternative measure of the robustness of activity to the unemployment rate, which is sensitive to those labour force swings.

The following graph shows the Employment-to-Population ratio, since February 2008 (the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

It dived with the onset of the GFC, recovered under the boost provided by the fiscal stimulus packages but then went backwards again as the last Federal government imposed fiscal austerity in a hare-brained attempt at achieving a fiscal surplus.

The ratio began rising in December 2014 which suggested to some that the labour market had bottomed out and would improve slowly as long as there are no major policy contractions or cuts in private capital formation.

The series turned again as overall economic activity weakened.

The ratio rose by 0.1 points in November 2018 to 62.3 per cent and remains well below pre-GFC peak in April 2008 of 62.9 per cent.

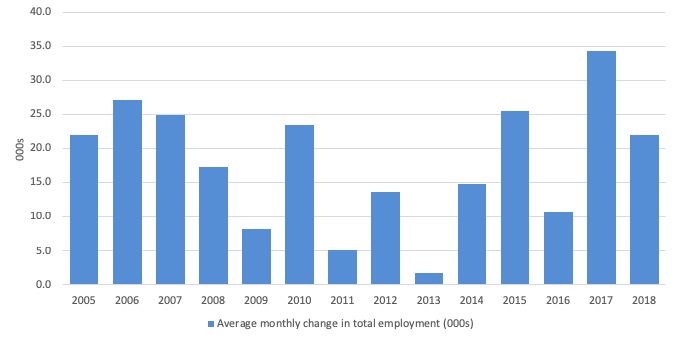

To put the current monthly performance into perspective, the following graph shows the average monthly employment change for the calendar years from 2005 to 2018 (the 2018 result is up to November 2018 only).

It is clear that after some lean years, 2017 was a much stronger year if total employment is the indicator.

It is also clear that the labour market has weakened considerably in the first 11 months of 2018.

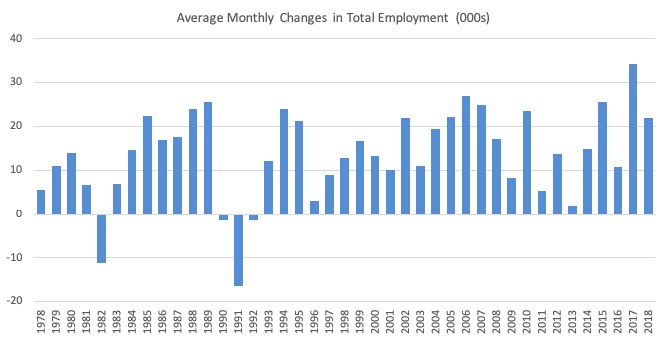

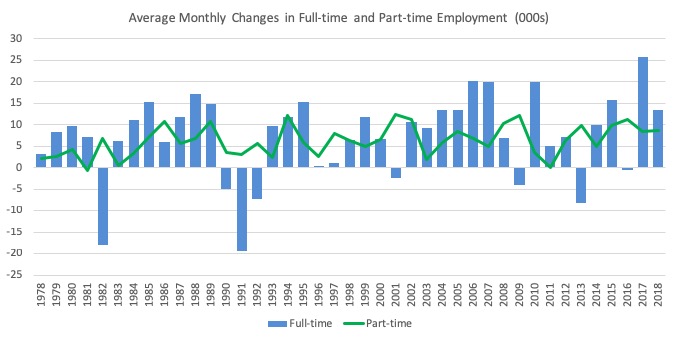

To provide a longer perspective, the following graphs shows the average monthly changes in Total employment (upper panel), and Full-time and Part-time employment (lower panel) in thousands since 1978 (when the current dataset began).

The interesting result is that during recessions or slow-downs, it is full-time employment that takes the bulk of the adjustment. Even when full-time employment growth is negative, part-time employment usually continues to grow.

Unemployment increased 12,500 to 683,100

The official unemployment rate rose by 0.1 points to 5.1 per cent mainly due to the participation rate rising by 0.2 points.

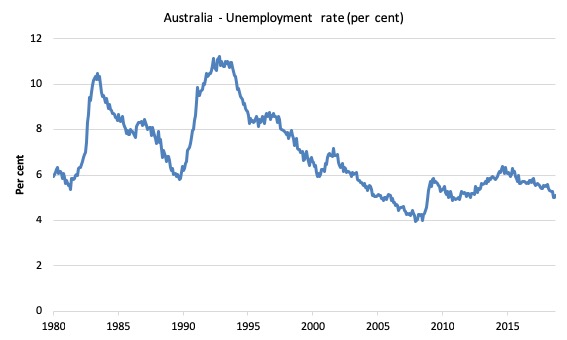

The following graph shows the national unemployment rate from January 1980 to November 2018. The longer time-series helps frame some perspective to what is happening at present.

Assessment:

1. It is still 0.2 points above the level it fell to as a result of the fiscal stimulus (which was withdrawn too early) and 1.1 point above the level reached before the GFC began.

2. There is clearly still considerable slack in the labour market that could be absorbed with fiscal stimulus.

Broad labour underutilisation up 0.3 points to 13.6 per cent

The results based on the Monthly data for November 2018 are (seasonally adjusted):

1. Underemployment rose by 0.2 points to 8.9 per cent (1,132 thousand)

2. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) rose 0.3 points to 13.6 per cent.

3. There were a total of 1,815.1 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

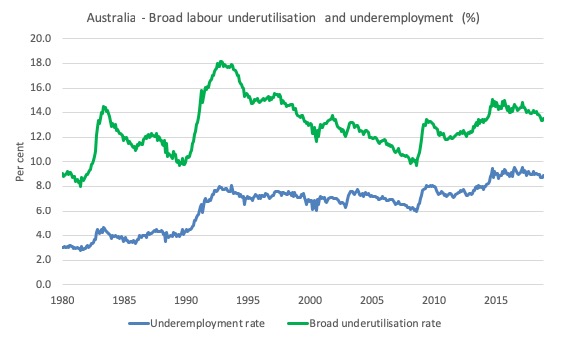

The following graph plots the seasonally-adjusted underemployment rate in Australia from January 1980 to the November 2018 (blue line) and the broad underutilisation rate over the same period (green line).

The difference between the two lines is the unemployment rate.

You can see the three cyclical peaks corresponding to the 1982, 1991 recessions and the more recent downturn.

The other difference between now and the two earlier cycles is that the recovery triggered by the fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 did not persist and as soon as the ‘fiscal surplus’ fetish kicked in in 2012, things went backwards very quickly.

The two earlier peaks were sharp but steadily declined. The last peak fell away on the back of the stimulus but turned again when the stimulus was withdrawn.

If hidden unemployment (given the depressed participation rate) is added to the broad ABS figure the best-case (conservative) scenario would see a underutilisation rate well above 15 per cent at present. Please read my blog post – Australian labour underutilisation rate is at least 13.4 per cent – for more discussion on this point.

Teenage labour market remains weak in November 2018

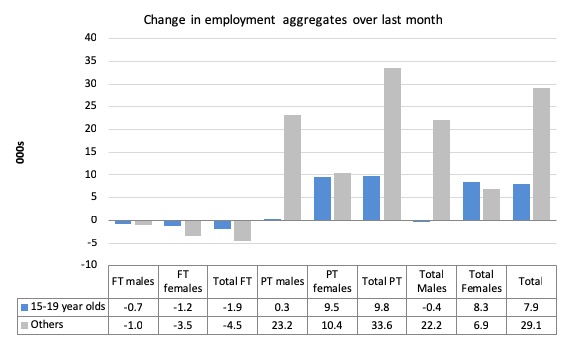

Total teenage employment rose by 7.9 thousand jobs in November 2018 with full-time teenage employment falling by 1.9 thousand and total part-time employment rising by 9.8 thousand.

The rise in part-time employment will be associated with the retailing boost from the season.

The following graph shows the distribution of net employment creation in the last month by full-time/part-time status and age/gender category (15-19 year olds and the rest)

Over the last 12 months, teenagers have gained 31.8 thousand (net) jobs overall while the rest of the labour force have gained 253.9 thousand net jobs.

Teenagers have gained around 11.1 per cent of the total net employment growth over the last 12 months but represent around 7.3 per cent of the total labour force. So they are doing slightly better when we take scale into account.

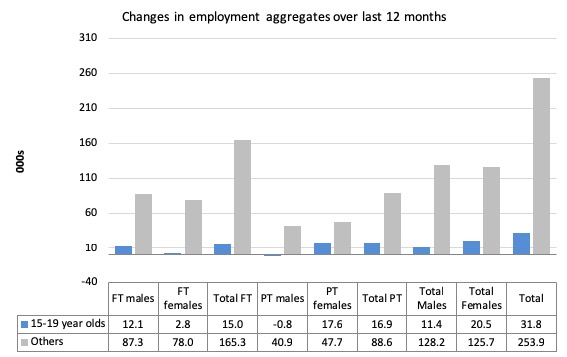

The following graph shows the change in aggregates over the last 12 months.

In terms of the current cycle, which began after the last low-point unemployment rate month (February 2008), the following results are relevant:

1. Since February 2008, there have been 2,046 thousand (net) jobs added to the Australian economy but teenagers have lost a 60.2 thousand over the same period.

2. Since February 2008, teenagers have lost 101.4 thousand full-time jobs (net).

3. Even in the traditionally, concentrated teenage segment – part-time employment, teenagers have gained onl 41.1 thousand jobs (net) even though 1,003.1 thousand part-time jobs have been added overall.

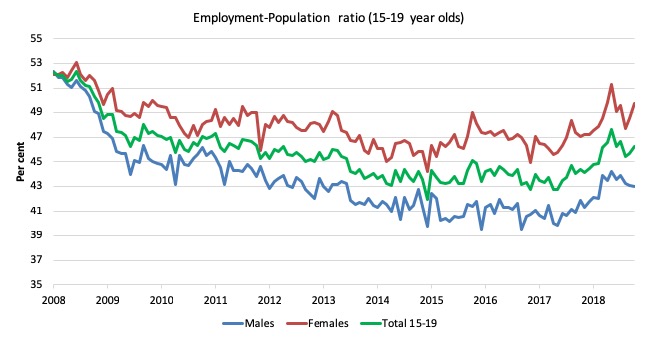

To put the teenage employment situation in a scale context (relative to their size in the population) the following graph shows the Employment-Population ratios for males, females and total 15-19 year olds since February 2008.

You can interpret this graph as depicting the loss of employment relative to the underlying population of each cohort. We would expect (at least) that this ratio should be constant if not rising somewhat (depending on school participation rates).

The absolute loss of jobs reported above has impacted more on males than females.

The male ratio has fallen by 9.3 percentage points since February 2008, the female ratio has fallen by 2.4 percentage points and the overall teenage employment-population ratio has fallen by 6 percentage points.

The other statistic relating to the teenage labour market that is worth highlighting is the decline in the participation rate since the beginning of 2008 when it peaked in February at 61.4 per cent.

In November 2018, the participation rate was 55.4 per cent (up by 0.5 percentage points).

However, the difference between the 2008 level, amounts to an additional 81 thousand teenagers who have dropped out of the labour force as a result of the weak conditions since the crisis.

If we added them back into the labour force the teenage unemployment rate would be 23.69 per cent rather than the official estimate for November 2018 of 16.5 per cent.

Some may have decided to return to full-time education and abandoned their plans to work. But the data suggests the official unemployment rate is significantly understating the actual situation that teenagers face in the Australian labour market.

Overall, the performance of the teenage labour market leaves a lot to be desired. The decline in full-time employment for teenagers was particularly worrying.

This situation doesn’t rate much priority in the policy debate, which is surprising given that this is our future workforce in an ageing population. Future productivity growth will determine whether the ageing population enjoys a higher standard of living than now or goes backwards.

I continue to recommend that the Australian government immediately announce a major public sector job creation program aimed at employing all the unemployed 15-19 year olds, who are not in full-time education or a credible apprenticeship program.

Hours worked fell 3.3 million hours (0.2 per cent)

The following graph shows the monthly growth (in per cent) over the last 24 months.

The dark linear line is a simple regression trend of the monthly change – which depicts a very flat trend – distorted somewhat by the outlier in May 2017 (the trend would have been more downward without that positive spike).

You can see the pattern of the change in working hours is also portrayed in the employment graph – zig-zagging across the zero growth line although less so in 2017.

The last several months have shown weakness.

Conclusion

My standard monthly warning: we always have to be careful interpreting month to month movements given the way the Labour Force Survey is constructed and implemented.

The November data shows that the employment growth was all due to part-time jobs growth (probably related to the Xmas season) and both full-time employment and hours worked were negative.

Not a good sign.

The moderate employment growth, however, trailed behind the growth in the labour force and unemployment rose a bit.

The broad measure of labour underutilisation rose by 0.3 points to 13.6 per cent with underemployment rising by 0.2 points.

Again, a sign of a weak labour market that is relying on part-time jobs for growth.

My overall assessment is:

1. The labour market remains in a fairly weak state – the growth in employment is not sufficient to match the growth in labour supply and the broader measures of labour underutilisation remain at persistently elevated levels.

2. It remains a considerable distance from full employment.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This document from the ABS says that in February 2018 there were 1.08 million Australian residents aged 15 years and over who were marginally attached to the labour force.

6226.0 – Participation, Job Search and Mobility, Australia, February 2018

Of the 1.08 million, 103 thousand did not actively look for work because they were discouraged job seekers.

793 thousand did not actively look for work for “Other Reasons”.

Does anyone know that the other reasons include?

At first I thought that perhaps the ABS defines discouraged job seekers as people who are discouraged about their own attributes e.g. age, skills, experience, and the “other reasons” category is for people who are fine with themselves but recognize that there are problems with the labour market. But then I saw that the definition of discouraged job seekers includes people who believe that there are

– no jobs available in their locality or line of work

– no jobs in suitable hours of the day

– no jobs available at all

So I’m not sure why the “Other Reasons” bucket contains eight times as many people as the “Discouraged job seekers” bucket that covers a very wide range of reasons related not only to the person’s beliefs about their own attributes but also the person’s beliefs about the nature of the labour market.

“6102.0.55.001 – Labour Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods, Apr 2007

PREVIOUS ISSUE Released at 11:30 AM (CANBERRA TIME) 19/04/2007

CHAPTER 7. NOT IN THE LABOUR FORCE

Discouraged job seekers

7.14 Discouraged job seekers are defined as people with marginal attachment to the labour force who want to work and could start work within four weeks if offered a job, but who have given up looking for work for reasons associated with the labour market. This group includes people who believe they would not find a job for any of the following reasons:

considered to be too young or too old by employers;

believes ill health or disability discourages employers;

lacked necessary schooling, training, skills or experience;

difficulties because of language or ethnic background;

no jobs in their locality or line of work;

no jobs in suitable hours; and

no jobs available at all.

This definition of discouraged job seekers is consistent with the definition of discouraged workers outlined in international guidelines.”

I’ll send an inquiry to the ABS.

Scott Marley from the ABS provided this reply:

Hi Nicholas,

Further insight into the differences between “discouraged job seekers” and “other reasons” can be found in Table 11 of the PJSM publication, which can be found under the Downloads tab

Other reasons mainly covers people whose ability to work or time available to work is hindered by some other need or reason, such as recovering from an injury, suffering from a long-term illness or disability, taking care of children or elderly relatives, or attending educational institutions to acquire new skills, These reasons are not considered to be related to feeling discouraged about actively looking for work and participating in the job market.