In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Eurozone fiscal rules bias nations to stagnation – exit is the remedy

It is Wednesday and I am doing the final corrections to our Macroeconomics textbook manuscript before it goes off to the ‘printers’ for publication in March 2019. It has been a long haul and I can say that writing a textbook is much harder than writing a monograph not only because the latter are more exciting in the drafting phase. The attention to detail in a textbook that runs over 600 pages is quite taxing. Anyway, that is taking my attention today. I also plan to write some more about Brexit in the coming weeks and Japan (tomorrow). But today, I have updated some ECB data on household and corporate borrowing and the cost of borrowing to see what sort of recovery is going on. With nations such as Germany now recording negative growth in the third-quarter, it is clear that the Eurozone is stalling again. The explanation doesn’t require any rocket science. It is all there in the behaviour of the non-government sector (saving more overall) and fiscal rules that are too tight to offset that saving desire. The reliance on monetary policy is an ineffective tool to provide the offset in non-government saving overall. Fiscal policy has to be reinstated to the primary position and that means nations such as Italy must consider exiting the dysfunctional monetary union that biases nations to recession and stagnation.

Euro bank lending

I was updating my database for some commissioned work I have been doing for a Eurozone institution today.

I won’t go into detail of the work but the summary results of some of it are interesting.

I last wrote about this data in this blog post – The ECB could stand on its head and not have much impact (February 2, 2016).

The mainstream New Keynesian macroeconomics logic that a reliance on monetary policy for counter-stabilisation does not accord with the forces that drive the economic cycle.

The belief that banks will suddenly lend just because the central bank imposes a tax on their reserve deposits (negative interest rates) or offers them cheap loans to on-lend to households and firms is misplaced.

Banks do not loan out their reserves and firms will not borrow from banks no matter how cheap the money is if there are no profitable opportunities to pursue.

It is time the authorities abandoned their neo-liberal myths and got real.

The Eurozone needs a massive fiscal expansion and it needed it 7 or 8 years ago.

The ECB is the only institution in the flawed system that can provide the financial resources to make that happen and it could, with Brussels approval, bypass the ‘no bailout’ clauses in the Treaty to make that happen.

The Italian situation at present is all down to the flawed institutional structures of the common currency.

The massive Asset Purchase Program (APP) conducted by the ECB is, in reality, funding fiscal deficits in the Eurozone.

Without that program, which is strictly breaking the laws of the Treaties, the Eurozone would have broken up years ago.

The primary buyers of the government debt know with some certainty, given the size of the APP that the ECB will buy the debt they wish to off load.

The ECB, itself, has said that the APP is all about “maintaining price stability” it also says that the program will:

… also help businesses across Europe to enjoy better access to credit, boost investment, create jobs and thus support overall economic growth, which is a precondition for inflation to return to and stabilise at levels close to 2%. Subject to price stability, these are also important objectives to which the ECB contributes in line with the Treaty.

So the ECB wants us to believe that pushing more reserves into the banking system will act as a stimulus measure to lending.

Anyway, I checked the latest data this morning.

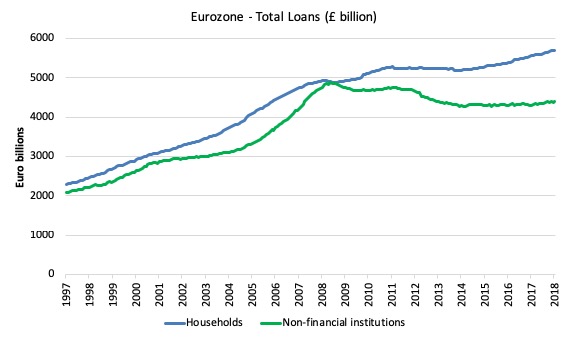

The first graph shows the total loans to households and non-financial institutions (that is, businesses that produce goods and services rather than shuffle money) in the Euro area from September 1998 to September 2018 (this is the entire sample provided by the ECB Statistics Warehouse.

The data is not “adjusted for sales and securitisation”, which the ECB define as “Adjustment for the derecognition of loans on the MFI balance sheet on account of their sale or securitisation.” In other words, the risk is sold off to some other speculator or another. They only started making that adjustment in January 2009.

The boom then the crash. While the household credit aggregate is now a little higher than before the crash, business borrowing remains well down and despite the ECB efforts.

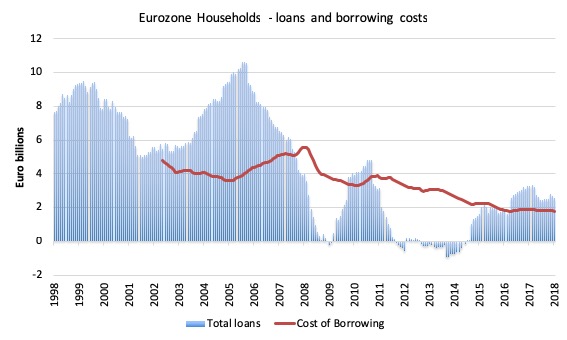

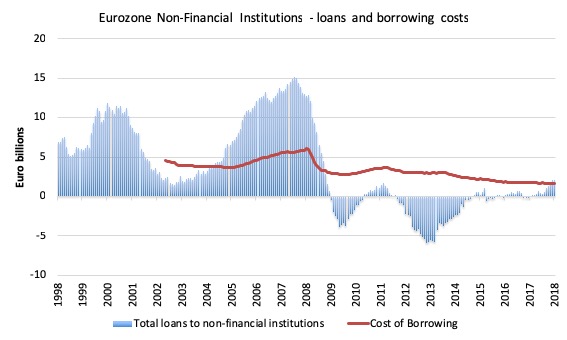

The next graph shows the annual percentage change in borrowing by households (upper panel) and non-financial institutions (lower panel) from January 2003 to September 2018. The red lines are the respective cost of borrowing for each sector (which is only available from January 2003).

There you see the credit binge in both sectors prior to the crisis and the subsequent collapse.

The growth rate in household loans is now falling even though the cost of borrowing is also falling and the response by corporations is weak, to say the least.

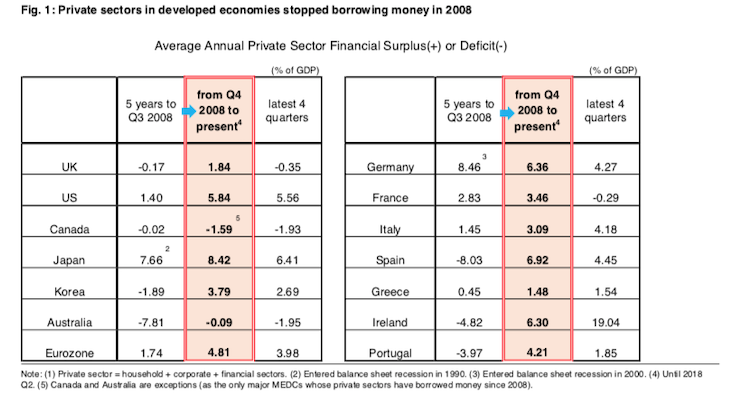

Now consider the following Table which is taken from Fig. 1 in the November 20, 2018 Nomura Briefing from Richard Koo (not available publicly).

It shows the “changes in private-sector savings in various economies before and after the GFC erupted in September 2008”.

Richard Koo writes that:

The table makes it clear that the private sectors in both the US and the eurozone have been running large financial surpluses ever since the housing bubbles burst. In the eurozone, this surplus has averaged 4.81% of GDP from 2008 Q4 to the present.

He is referring to the private domestic sector.

Now unless that private domestic is offset either by an external surplus and/or a public deficit, real GDP growth will decline and unemployment will be higher than otherwise.

These private surpluses are why borrowing in the Euro area has been so weak.

The importance of thinking in this way is to allow one to reach an understanding of how damaging the Eurozone fiscal rules have been (Stability and Growth Pact and then the stricter Fiscal Compact).

Richard Koo writes:

… the Maastricht Treaty’s 3% deficit cap and the 2013 Fiscal Compact have prevented governments from implementing the fiscal stimulus needed to borrow and spend this 4.81% surplus. Any private-sector savings in excess of the deficit simply dropped out of the income cycle, prompting sustained weakness in the eurozone economy.

Which is true for the Eurozone but only partially true for a currency-issuing government such as the US, UK, Japan, Australia etc.

The difference lies in the phrase “needed to borrow”.

For a currency-issuing government, the government doesn’t need to borrow these savings. What it needs to do is to make sure they are offset by spending, after adjusting for an external balance reality.

So in the case of most nations, which run external deficits, the fiscal deficit has to not only offset the drain in spending from the external sector, but also the overall private domestic saving.

Otherwise, you get recession and stagnation.

In the Eurozone, the governments do have to borrow in order to run deficits because they unwisely opted to use a foreign currency, the euro.

And the fiscal rules are so restrictive that these governments are unable to borrow enough and spend enough, with the result being their poor economic performance with elevated levels of unemployment.

The Eurozone can never be successful on a sustained basis while these rules are in place and operational.

That is why countries like Italy must break out and restore their monetary sovereignty.

And don’t buy the stupid line that monetary sovereignty is about being able to buy everything a nation might need to be prosperous. Being in that position is a different state altogether.

Monetary sovereignty means that the currency-issuing government can purchase anything that is available for sale in that currency including all idle labour. So no productive resources ever need to be idle if they are looking to be used.

That doesn’t mean a poor country will be rich! That is a different thing altogether.

Conclusion

Given the scale of the monetary policy interventions over the last year or two one would have expected a much stronger growth in loans, particularly for non-financial institutions if the logic of the central bank was sound.

The central bank can clearly use its currency-issuing capacity to prevent a massive financial meltdown. It can clearly stop governments in the Eurozone from going bankrupt as it did between 2010 and 2012 with the Securities Markets Program.

But what monetary policy in any of its forms cannot do is reverse a major recession where mass unemployment and income losses create deep pessimism among households and firms.

Monetary policy does not work to offset non-government saving in the way that fiscal policy does.

This is especially the case where the relevant fiscal authority (a questionable term in the case of the Eurozone) is intent on maintaining a straitjacket of austerity, which chokes off any green shoots in economic activity.

The big motor is fiscal policy and because of the flawed design in the Eurozone it is dysfunctional in the extreme. Central bank policy shifts can do little to counter the damage that fiscal austerity is doing in Europe.

Music I am listening to as I work today …

This track – Swedish Prison – is from the US band – 10 Foot Ganja Plant – and is from their Bass Chalice album, which was released in 20015 on Reach Out International Records (ROIR).

Its funky, its jazzy and its reggae – how could one go wrong?

It often turns up on my play list.

Something good coming out of America!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Would those governments who leave the EU(Brexit or Exit) not be enthrall to the same neoliberal arguments that those governments espouse now? The “Gilets Jaunes” movement in France is certainly about the continued austerity in the EU. Taxes on fuel may be the rallying cry however larger issues are more the driving force. Politically the next step in Brexit is probably continued Conservative rule or a John McDonnell 5 year plan to balance the budget both neoliberal/austerity constructs. I personally am with you on MMT policy answers but the breakup of the EU is not going to get you/us what we would like. Sadly I feel it will bring us a xenophobic oligarchic autocracy worse than the one we have now.

Dear Heim (at 2018/11/21 at 5:59 pm)

You are right, exit doesn’t guarantee anything progressive.

But it is a necessary, rather than a sufficient condition for progressive government.

That means staying in makes it nigh on impossible to have an broad-based progressive agenda and defend the economy from cyclical meltdowns.

At least exit, restores the unity between economic policy and the democratic process, which means if the people want progressive policies they will vote accordingly.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill

I’ve been puzzling over this for a long time, hoping light would eventually flood in of its own accord – but it hasn’t, so I’m forced to ask what is doubtless a dumb question:- what do you mean by the term “counter-stabilisation”? As in:- “The mainstream New Keynesian macroeconomics logic that a reliance on monetary policy for counter-stabilisation does not accord with the forces that drive the economic cycle”.

Isn’t “stabilisation” good per definition and, if so, why would “countering ” it be a desirable aim? Or am I hopelessly at sea? It’s obvious that I’m missing something important…

Dear robertH (at 2018/11/21 at 6:42 pm)

Counter to the non-government spending cycle.

When it is in decline, the government spending cycle must work to counter it and vice versa. The counter-cyclical policy stance is the way in which government can stabilise the cycle and avoid booms and busts.

That is the meaning of the term.

best wishes

bill

To Heim.

The main difference is that if government chooses to do other economic policy (say big deficits) it is free to do so, there are no legal restraints (or very few) of doing that. In Eu you can’t because every nation would have to agree to change the rules and that is simply not feasible, especially today or in the near future.

This is a great blog in that it give a concrete numerical example to show how deficits need to fill gap left by savings. And the difference between sovereign and eurozone countries in the need to borrow the savings. Made things very clear.

Heim says:

“Sadly I feel it will bring us a xenophobic oligarchic autocracy worse than the one we have now”.

Could it be any worse?

At least when the would-be oligarchic autocrats live in more-or-less-close proximity to the potential wielders of pitchforks they are more likely to exercise circumspection – and history shows that the worm can sometimes turn surprisingly fast.

Whereas when they’re all ensconced in their Brussels citadel/self-reinforcing groupthink bubble, they believe they’re immune from any popular reprisals – and seem to have been entirely justified in that belief by events so far. They have been allowed – emboldened even – to get away with murder (almost literally in the case of Greece) with complete impunity.

.

Dear Bill

You told me, at GIMMS launch, that you supported LVT so I do hope that ‘Macroeconomics’ will reinstate land as an integral part of the economy. I hope that land is given a clear definition, not just bare fact that it has fixed supply and illustrated by the usual trivial supply/demand curves. Some wise words I heard from Mason Gaffney many years ago: usable land that is unused is a permanent loss to production. That should be seen as an addition to the normal concerns about unemployment.

The neoliberals have deliberately conflated land with capital. It was just as deliberate as the money trick. See Mason Gaffney’s ‘The Corruption of Economics’.

I would like to see a discussion of how the land market is the most dysfunctional important market which has huge consequences for wellbeing, not least in providing one of the basic necessities of life: housing. It’s rent-seeking in its pure form. I would assume that you evaluate land value tax as the best form of taxation. Economic textbooks usually have a section on LVT but it needs to be linked to the bigger picture.

I won’t be saving to buy a copy if land is ignored again. You will be doing students a great disservice.

Best wishes.

Carol

Bill I’m no economist but It escapes me why it’s always assumed the centre/Gov is where money should be created. If we are to rely on borrowings from banks to build the economy and the banks insist on collateral then whatever is deemed to be collateral is always going to grow more expensive, leading to ever increasing ‘on’ costs and interest payments to the banking sector. What would be the effect of allowing citizens a direct line of credit, a sum similar to a living wage, which would automatically be taxed back, at say 2.5%, with every transaction, and each years debt treated seperately, so say 7 years 7×2.5% with the payment paying down the oldest debt first?

Dear Bill

Thanks for that (breathtakingly swift) reply.

Please forgive me if I seem to be trying to teach my grandmother to suck eggs, but wouldn’t it be simpler (and more helpful to my fellow-ignoramuses (ignorami?)) to just simply write “counter-cyclical”? I believe that is a generally well-understood term whereas (unless I’m in a minority of 1) “counter-stabilisation” isn’t. And – if I’ve (now) understood correctly – aren’t they synonymous?

Just a suggestion – I hope a constructive one.

Regards (and with much admiration of your tireless endeavours)

Robert

@ Heim:

This is something I have also expressed concern about under past posts. It’s not, that I don’t recognize the “left argument for Brexit” or an analogous argument for Italy to leave the MU, but rather that I see the figures spearheading the movements either as even more extreme free marketeers or as xenophobic authoritarians. In a way, it is not a decison that differs much from that the Americans had to make in Trump vs. Clinton, even if the fight was fought under the guise of “identity politics” rather than economical arguments.

@ all:

I have been putting some effort in debating my fellow Germans in rather left-wing forums about the necessity of abandoning the “Schuldenkult” (cult of debt) and the “swabian housemaid” as a paragon of economic behavior, but even there I have seldom encountered such thick skulls. To the country that experienced its “Wirtschaftswunder” (economic miracle) on the back of the biggest debt haircut in history and a colossal economic stimulus package (Marshall Plan), it appears to be too much to ask that they treat countries indebted due to mismanagment by european and their elites the same way the country that tried to erase a human race an enslave a big part of the world was treated. Ironically, the deny them the opportunity given to us less than 70 years ago on the grounds of morality(!!!). However, the most accurate accounting on the basis of sectoral balance or the best arguments for fiscal stimulus do not reach those who let their “morality” dictate their economic thought. I have considered taking the approach of addressing the fact that this morality is upside down to begin with from another perspective.

When doing this, Icame across the most recent work of Prof. Michael Hudson. In his work, Prof. Hudson revisists the ancient Babylonian concept of chronically forgiving the debts to the palace by peasants and workers during the so called “jubilee year”, since those debts always rose faster than their earnings. Additionally, the issuance of private credit was subject to very strict regulations in order to protect debtors unable to pay fromm falling into bondage to their creditor (working on his land, they ultimately ended up losing theirs). This was part of Babylonian law (Hammurabi’s Codex) and eventually became part of the jewish religion. It is Prof. Hudson’s and many other’s interpretation of the dead sea scrolls, that Jesus was a rabbi that fought to reinstall this tradition, long ignored by the rulers, merchants an temples of the time. Hence, the “cleansing of the temple” episode in the bible. Understandably, this wasn’t in the particular interest of those in power back then, which rendered Jesus a rather… unsavory character to their eyes.

After that rather long excursion, I’d like to muse about debt forgivness in the context of MMT. Obviously, addressing the debt owned “to the palace” can easily be “forgiven” and has, at least in developed nations, never really been the problem. In Germany, I have never heard of anybody bankrupted by his public student loan: you only have to repay half the sum lent to you at a 0% interest rate and not at all if your income isn’t high enough. However, are there good reasons not to let bad private credits go belly up? It is my understanding, that since its a “horizontal” transaction in the context off MMT, net financial assets would neither be created nor destroyed in the process. Wouldn’t numbers simply shift from one account (say -100 –> 0 in the students account) and be offset by the numbers in the other account (100 –> in the bank account)? Would “rewarding this bad behavior” deter banks from issuing their next loan? It is my understanding that the minute a credit worthy customer walks though their door is the minute a bank is willing to make a deal.

P.S.: In other posts people were discussing the consecuences of defaulting on the US sovereign debt, but there is no sense in defaulting, since there is absolutely no need for them to default on any debt denominated in US$, so I’ll leave that one out.

This “exit is the remedy” proposal does not, however, tie in with the democratic wishes of the EU population, if this poll is to be believed.

https://twitter.com/LBiniSmaghi/status/1064774679775363072

People who answer these polls in countries like Greece and Italy remember what it was like to be outside the Euro with a floating exchange rate. The Greek Drachma would devalue against the German Mark by maybe 10% each year to keep the country competitive, making up for higher inflation in Greece compared to Germany. At the same time, many Greeks had to seek employment in Germany, even then. The same was true for Italy, only on a smaller scale.

So Eurozone Europeans want to keep the Euro, despite the evident shortcomings. Currency devaluations make citizens poorer when compared to citizens of other countries. In a small area like Europe a citizen’s purchasing power and perceived wealth is very much determined by comparing yourself to a citizen of a neighbouring country.

Italians currently discuss how to overcome this by introducing a parallel currency. I am not sure why Bill does not discuss this parallel currency idea in more detail, setting out advantages (it basically overcomes the Euro fiscal rules) by keeping a country in the Euro area at the same time. There is no need to leave the Euro, but there is a possibility to reflate the economy if a country wishes to do so.

Bill should discuss his view on this in more detail – clearly there is an interest in it – not sure why he does not.

Hermann,

‘it appears to be too much to ask that they treat countries indebted due to mismanagment by european and their elites the same way the country that tried to erase a human race an enslave a big part of the world was treated. Ironically, the deny them the opportunity given to us less than 70 years ago on the grounds of morality(!!!).’

Well put! The moral bankruptcy re. Greece, Spain etc is quite staggering showing that the EU as a force for European unity is a chimera an hallucination of the so-called progressive(not) ‘Left’.

We know from history that debts can be ‘disappeared’ when the political will is there. Economist Richard Wolff has talked about the Geek debt as being legally definable as ‘odious’ and perfectly cancellable.

With regard to student debt I think Scot Fullwiller has done some serious accounting work on that which is available in a Levy Institute paper: http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/the-macroeconomic-effects-of-student-debt-cancellation

This should address your questions, though I haven’t read it fully myself as I seem to run out of brain power too quickly 🙁

The problem with this debt is that it is often packaged in tranches and sold all over the global financial system. I’m not sure if that applies to Student debt which might be held by quasi Governmental institutions as in the Student Loans Company in the UK. If I remember correctly some of this has been sold-off and is bouncing around the financial system in some form-but I’m not sure of my facts here. How a write of affects the solvency of the financial institutions affected is not clear to me -maybe let them go to the wall ( if it doesn’t compromise the payment system) or swap bonds for the debt?

I agree, Michael Hudsons work is interesting. of course the word ‘Jubilee’ comes from a Hebrew word so these societies understood that excessive debt accumulation was ultimately a form of self-harm.

Herman the German. Guten Tag. Getting through is of the greatest importance. Try this tack.

The saving that takes place in Germany doesn’t happen at the household level – it happens at the national level. It is the result of policies imposed upon the household sector. Hartz Reforms. The wealthy and the powerful impose restraints, drive down the wages so that the people of the country can’t afford to buy all the goods and services produced there. They want the savings so that they can export them to another country and build up claims against the people there. The wealthy and the powerful see no advantage to themselves in sharing with their countrymen. Sure, I understand that would build some resentment amongst the denied, the ones upon whom sacrifice is imposed. Tell them a just and righteous country wouldn’t run large persistent trade surpluses. It is always a sign of economic injustice and exploitation. Tell them not to look down, down at the people who have less than you, who struggle, and are deprived more. Tell them to look up, up at the wealthy and the powerful and blame them. At a time when the inequality of income and wealth is so great, breakthrough and realize they are the ones who are taking.

As Edward Bellamy astutely pointed out during America’s First Gilded Age, when international commerce was rapidly expanding, the dismal choice for the average citizen, under a capitalist system, was between being fleeced by foreign capitalists or by domestic ones. Bellamy’s two masterworks, “Looking Backward” and “Equality,” are free to read on the net and offer a treasure trove of eviscerating insight into the inherent evils of capitalism AND a shining vision of what it might look like, actually FEEL like, to live in a much better, far more beautiful post-capitalist world. The dovetail between various aspects of Bellamy’s vision and the basic principles of MMT are thought-provoking and, to me, inspirational.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/11/19/on-earth-as-in-heaven-the-utopianism-of-edward-bellamy/

The latest government changes in Argentina and Brazil seem to suggest that the austerity model is alive and thriving in South America.

HermannTheGerman @19:55,

In regards to your question about cancelling debts owed by some members of the private sector to others in the private sector and whether there are good reasons not to do that in the context of MMT, my opinion would be yes- there are some good reasons if you want people to be able to borrow from other private sector entities (like banks) in the future.

MMT shows that banks ‘create’ the money for the loan (as a deposit in their accounts) at the time of the loan, but also recognizes that they have to fund that loan when that deposit is withdrawn or transferred to some other bank’s account. Banks can ‘fund’ the deposits they create in various (and often quite creative) ways not available to most private people, but usually at some cost to themselves that also may involve creating additional liabilities for themselves. So if (honestly operated)* banks can’t depend on getting repaid almost all of the time, they are not going to be making many loans. And the costs of borrowing from them (interest rates and fees) are going to go up. So yes- banks would be ‘deterred’ from making loans if they were costing them more to make than they got back in repayments.

But you also qualified your question by asking about ‘bad’ loans. At the very bottom of the Hudson article you linked to the other day it stated “Debts that can’t be paid, won’t be paid.” That has got to be true and it is probably better for everyone involved to recognize that sooner rather than later.

*Bill Black has much to say about dishonestly run banks and ‘control fraud’ in various posts at the New Economic Perspective blog. Very interesting stuff, especially if you hold a grudge against bankers.

Hi

Two suggestions for HermannTheGerman and Johnm33

HermannTheGerman says:

Wednesday, November 21, 2018 at 19:55

I think Bill is asked about debt jubilees in this interview http://pileusmmt.libsyn.com/11-bill-mitchell-mmt-qa-central-banking-job-guarantee-and-more

johnm33 says:

Wednesday, November 21, 2018 at 19:35

Forgive me if you’ve already absorbed all the non-academic MMT resources including the vast fund of knowledge generously donated by Bill in the form of 15 years worth of these blogs, but I wonder if you could put your suggestion in context yourself if you looked deeper into some of these resources covering the relationships between government spending and bank lending and their effects. I learn best nowadays watching or listening to lectures and interviews. Deficit owls youtube site has a treasure trove of them at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCWXGA051bB7uXlvsiGjvOxw/

Cheers, John

Hermann,

I don’t see how you make the distinction between bankruptcy and debt forgiveness? In Australia, at least, it will clear all of your unsecured debts with the exception of fines and debts incurred by fraud.

Yes, there are consequences for the person in that they are only discharged from bankruptcy after 3 years, but that only affects their ability to obtain further credit (which they shouldn’t be doing for obvious reasons), they can’t run a company, and prevents them from some jobs in the finance sector such as auditing.

But lets say you have built up $100,000 worth of credit card debt? The bank has no recourse, and if your home and car are under a secured mortgage, or worth less than a statutory amount, they are not affected.

Bill,

Is this sentence missing a word where I put the blank?

“Now unless that private domestic _______ is offset either by an external surplus and/or a public deficit, real GDP growth will decline and unemployment will be higher than otherwise.”

Frances Coppola has some ignorant things to say about monetary sovereignty. She does not appear to understand the distinction between financial constraints and real resource constraints. She does not appear to have read much or any of the core scholarship of modern monetary theorists.

@ Simon, Jerry, John:

Thanks for your links/input.

@ Yok:

Believe me, I try every day. Most people here doen’t get over the fact that no money has been flowing out of Germany to sustain those lazy southeners. They are actually kinda offended when one points out that this is not the case. They are convinced that it was people “living beyond their means” that brought the crisis upon Europe. Banks? Nah, that had nothing to do with anything…

@ Jerry:

Indeed, I was talking about bad loans. What disturbes me is the bias in favor of the creditors in media and politics. You make a bad deal, you lose your investment. That’s why you are paid interest on your loans. Essentially, the creditors demand maximum “responsability” of their customers, while they avoid anything resembling accountability themselves.

@Matt B:

You’re right. I didn’t make any distinction. I’d say that no one credit should force anybody into bankruptcy. To put it differently, if you can’t meet your car loan payments without compromising your mortgage payments, it should be possible to defaul on your car loan without having to go through a bankruptcy process and losing all.

It was my understanding that the private bankruptcy process is unnecessarily devastating as opposed to an enterprise bankruptcy (in the US). I thought this is no coincidence either, since the system is rigged for the upper class to ensure their fees and rents. However, if it is anything in the US as you describe for Australia, one should expect defaults on car and student loans to skyrocket anytime now, right?

Nicholas says:

“Frances Coppola has some ignorant things to say about monetary sovereignty. She does not appear to understand the distinction between financial constraints and real resource constraints. She does not appear to have read much or any of the core scholarship of modern monetary theorists”.

Doesn’t surprise me in the least. She already knows all that’s worth knowing (in her own not-so-humble opinion) so why would she trouble to learn anything new? More comfortable to just go on pontificating, as a self-appointed oracle.

She’s not alone, alas. As has been said by others we have to wait at least another generation (by which time I for one will be long dead).

Apologies for the pessimism. But, as Roger Scruton says, pessimism is preferable because then you can always be pleasantly surprised!

I wonder if Hard Brexit plus unilateral free trade would work for the UK? A number of other social policies would be necessary at the same time. A Job Guarantee and a proper social safety net would be an absolute requirement under that scenario. Of course, the UK would retain its sovereign (and floating) currency.

The problem would seem to be that all the necessary, complementary policies would have to be enacted and implemented rapidly and simultaneously. Unilateral free trade without a Job Guarantee and a full social safety net would be a disaster for poor people.

John thanks for the response, my question was more political than economic, though I do wonder how it would work economically. It being the creation of money [as debt] being a simple transaction between the state and the citizen, instead of the citizen having to compete for the handouts of goverments, or for the ‘money’ created by either the banks or the political elite. My grasp of MMT, at least in response to Bills questions could be explained as luck, too close to chance over time.

john

Aging populations, different kind of pensions systems, forced saving, pre-saving, tax incetives

All those could work keeping saving desires abnormally high.

Germany and Japan especially seem suspiciously high private sector saving, but I don’t know anything how their pension systems are arranged.