I am stuck in London courtesy of the terrorist policies of Donald Trump and his…

The flexibility experiment in Portugal has largely failed

Portugal has been held out by the Europhile Left as a demonstration of how progressive policies can manifest in the European Union, even with the Fiscal Compact and the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). In 2015, after the new Socialist government took over with supply guarantees from the Left Bloc (Bloco de Esquerda) and the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and The Greens (Partido Ecologista “Os Verdes”), it set about challenging the austerity mindset that has blanketed the European continent in stagnation. Things improved in 2016 with increased government spending. But by 2017, the European Commission had reasserted its austerity mindset and the supposed flexibility that the Left were hoping and which Portugal had briefly embraced in 2016 was gone. And we learned that the neoliberal bias of the Eurozone and its fiscal rules dominates any progressive ambitions that a nation state might entertain. Another blow for the Europhile Left. The lesson: start looking at and supporting exit if you are truly serious about restoring a progressive policy agenda in Europe.

An interesting recent discussion paper – The alternative nature of the Portuguese economic policy since 2016 – written by academics Luís Lopes and Margarida Antunes and published by the EuroMemo Group (November 2018).

It argues that the election of the new government in Portugal “roused great expectations at the political, economic and academic levels” because it:

… was an unusual experience within the Eurozone since the new government intended to reconcile the fulfilment of European budgetary rules with a household income led growth policy. This approach clearly departed from general European government policies as well as from the economic policy guidelines prescribed by the European institutions.

It was also seen as:

… a test of the member states’ autonomy in the design of their own fiscal policy as well as a test of the Eurozone and its political capacity to frame alternative economic policies.

However, after an initial period of ‘flexibility’ in fiscal policy, the experiment has demonstrated that the hard austerity bias embedded in the Eurozone’s fiscal rules dominate and the “alternative nature of the macroeconomic policy” in Portugal began to dissipate in 2017 as the Government became focused once again, under pressure from Brussels, on “reducing public debt”.

The lesson is that the limited flexibility within the Eurozone rules is not sufficient to sustain improvements in household income and “improve public services quality and public infrastructure within the context of European budgetary rules”.

Which means that Brussels, not national governments, ultimately determine the quality and scope of public service delivery in “health, education, social services, and transport” because the European-level technocratic fiscal rules compromise any meaningful autonomy at the democratic level of elected governments.

And so the Europhile Left’s love affair with Portugal as a beacon of hope fades into the morass of Brussels-led repression.

What the data tells us

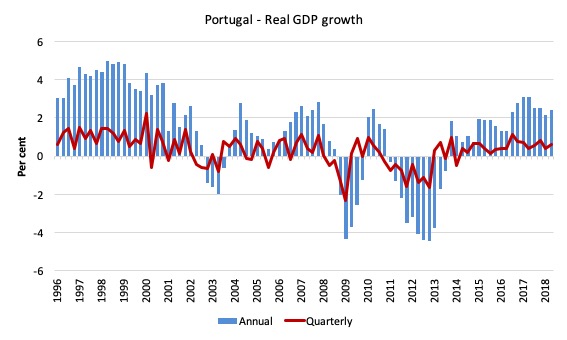

The first graph shows the evolution in real GDP growth (quarterly and annual) in Portugal since the March-quarter 1996.

We can clearly see that after the crash there was a faltering period of positive and variable growth at low levels until the new government came to office in November 2015.

Then followed three to four quarter of solid growth.

However that boost is now over and while the economy is still growing it is falling back into a much lower growth path.

I will discuss why later.

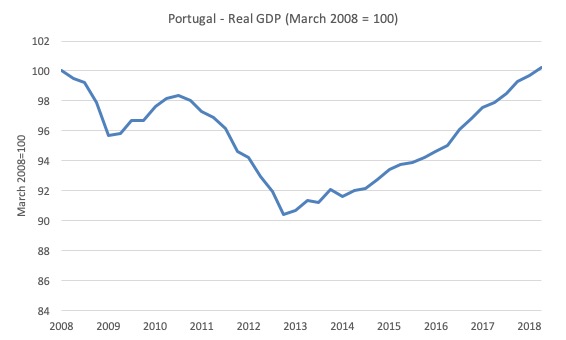

The next graph shows the Real GDP index (March-quarter 2008 = 100) from the peak of the last cycle to the June-quarter 2018.

The most recent quarter is notable because it is the first time in more than a decade that Portugal’s economy has risen above the level it was at when the GFC began and the austerity mindset started to shrink the economy.

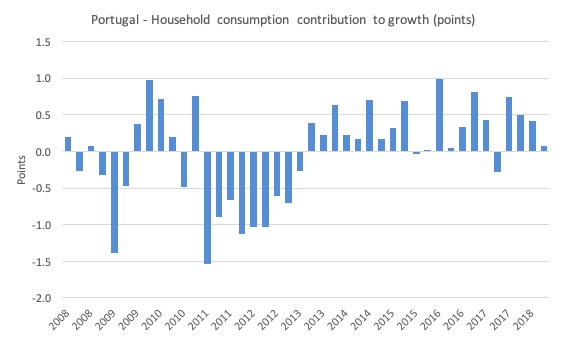

As I discuss below, the Government made a concerted effort to stimulate household disposable income.

The response was that household consumption expenditure contributed solidly to growth in 2016 and into 2017, although that impact is now fading.

But we have to put that into perspective.

In level terms (the actual euro outlays by households on consumption goods and services), the household sector is still below the March-quarter 2008 level.

As the EuroMemo paper notes:

… private consumption, which has been penalised in such way by the crisis that in 2017 had not yet reached the value of 2008.

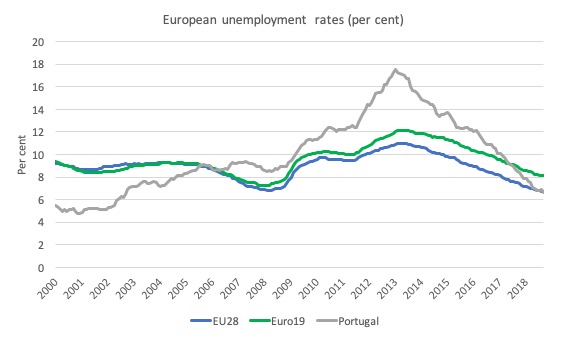

The labour market did improve in 2016.

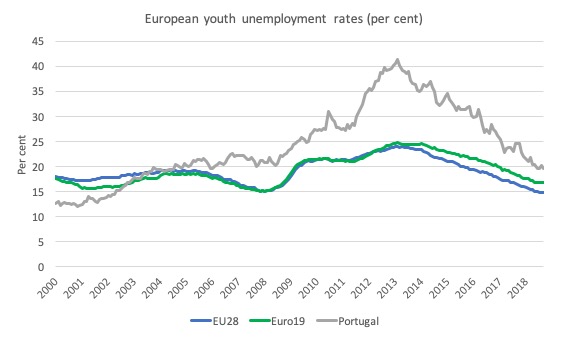

The following graphs show the evolution of Portugal’s overall and youth unemployment rates compared with the EU28 and the Eurozone Member States

Portugal is doing relatively better than the rest of the Eurozone average in overall terms although its youth unemployment rate is still well above the levels achieved by the EU and Eurozone overall.

However, the share of fixed-term contracts rose in 2017 to 18.3 per cent (from 16.9 pre cent) so while, employment has grown so has the precarious nature of work increased.

The EuroMemo paper reports that:

1. “there have been no important changes in wage conditions”.

2. “in 2017, the wage share was 2 p.p. lower than the 2007 level”.

3. “In 2016 there has been a rise of the real wage by 0.4% and in 2017 by 0.6%” and that has been concentrated at the lower end, partly due to the “increase of the minimum wage by 10% during 2016 and 2017”.

4. But, “The number of full-time employees earning the minimum wage has increased. In April 2008 they were 6.8%, and 25.7% in April 2017”.

Fiscal policy orientation

The EuroMemo paper reports that:

The 2016 Portuguese budget was the first since 2010 especially designed to operate as an instrument for an expansionary demand-side economic policy.

The Government aimed “at improving household disposable income” by:

1. Restoring public sector wages to pre-crisis levels.

2. Eliminating “the personal income surtax that had been imposed in 2011”.

3. Unfroze “retirement pensions that had been frozen in 2010, and the increase of the lower ones”.

4. Restored “some social benefits to their 2011 value” and increased “most of them”.

5. Introduced “employment measures to foster permanent job contracts.”

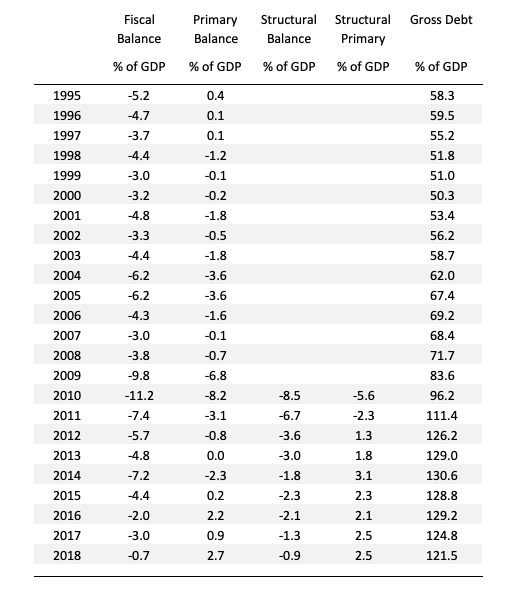

The following Table complements the EuroMemo paper’s “Table 1: Indicators of Public Finances, General government, % of GDP, 2011-2017”.

I have included data back to 1995 and not shown the year-to-year variations in the aggregates. You can mentally work them out pretty easily.

What the data shows is that the fiscal shifts from 2010 have been dramatic and even in the ‘expansionary’ period, the fiscal balance did not violate the SGP rules.

And while the public debt ratio rose marginally in 2016, it is clear that the direction is downward as the primary balance goes heavily into a contractionary setting.

Given the scale of the labour underutilisation and poverty, the fiscal expansion was very modest indeed.

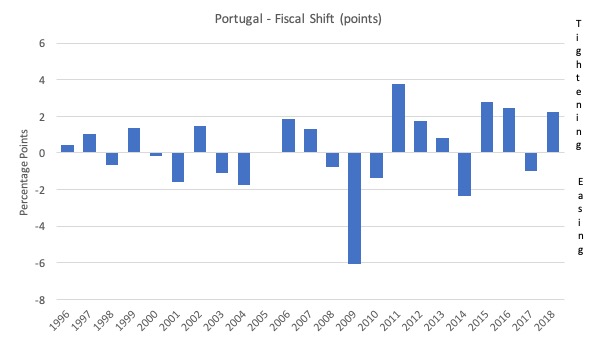

The next graph shows the year to year fiscal shift (change in points) for the overall fiscal balance – a positive number indicates a tightening of fiscal policy overall.

The reason that the public debt ratio has fallen (despite the small rise in 2016) is a combination of the primary fiscal surplus and the fact that interest rates and inflation have been so low.

The EuroMemo paper tells us that in terms of the shifts in the primary fiscal surplus:

The main contribution to that result in 2016 comes from the expenditure side, which accounts for 83% of the reduction, while in 2017 it comes from the revenue side which has been responsible for 72% of the reduction.

In 2016, interest payments fell and there was a substantial:

… reduction in public Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) expenditure, the latter being sufficient to offset the increase of primary current expenditure reduction.

So while the Europhile Left were lauding the measures outlined above to improve household disposable income, the reality was that the Government was robbing the future to ‘pay’ for the present.

Public investment in 2016 was 28.9 per cent lower than it was in 2015.

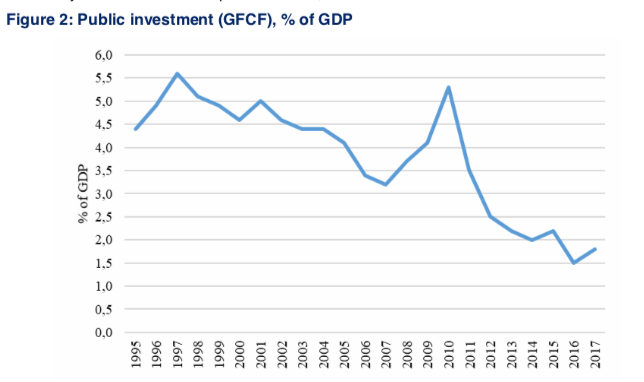

The following graph (taken from Figure 2 of the EuroMemo paper) shows the dramatic decline in public investment as a percent of GDP since 1995.

The first major reductions came during the convergence process to Stage 3 of the Maastricht Treaty where governments around Europe were cutting spending dramatically in order to meet the requirements to enter the monetary union. The austerity bias started long before the GFC.

Then as the European Commission started to demand major net spending cuts from 2010 despite the deep recession, the Portuguese government cut into public investment – in part, because it is easier to hide in the short-run than cutting recurrent spending.

The problem is that it undermines future prosperity.

While the deficit terrorists claim that running fiscal deficits to support growth mortgage the grandkids future, the reality is that austerity undermines the growth potential in the future and reduces opportunities for the next generation(s).

Overall, the fiscal deficit fell by 2.4 points, a contractionary move.

The rise in the fiscal deficit in 2017 is mostly due to an increase in public Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) but it was:

… less than half of the amount originally estimated and has been mainly applied in buildings (except dwellings) and local and regional governments.

But there was a 3.9 per cent growth revenue side (“more than the triple that of 2016”) mostly driven by higher activity and higher wages rather than rate hikes.

The overall conclusion is that:

The fiscal policy during these two years shows that there has been a tight control of government expenditure. In 2016, fiscal control has been focused on expenditure retentions as well as on public GFCF expenditure while in 2017 public GFCF expenditure was the main target. Although public GFCF expenditure has increased, it remained far below the programmed level and most of it did not result from a discretionary central government fiscal policy, but from decisions of local and regional governments.

So hardly a progressive dreamworld.

The EuroMemo research digs deeper and concludes that while there have been a number of policy initiatives that have reversed or attenuated some of the austerity measures taken by the previous government, it is apparent that the Government is still trying to reconcile their political mandate to end austerity with the “European budgetary rules”, which are all about austerity.

Even though the fiscal initiatives were hardly violating the Fiscal Compact (deficit was sitting on 3 per cent):

… the Portuguese fiscal policy generated some mistrust among European institutions throughout 2016. The possibility of sanctions has been repeatedly mentioned …

The European institutions made frequently clear that they did not believe that it would be possible to reconcile expansionary demand-side fiscal policies with the fulfilment of European budgetary rules.

On August 8, 2016, the European Council ordered Portugal to “reduce the general government deficit to 2.5 % of GDP in 2016” under the Excessive Deficit Procedure (Source).

It followed up on August 9, 2016, the Council relaxed the fine that was forthcoming under the mindless rules because of the size of the (Source:

… fiscal adjustment undergone during the economic adjustment programme which was accompanied by a comprehensive set of structural reforms …

… and because Portugal was committed to further fiscal tightening.

The EuroMemo paper reports that:

Therefore, for three years (2017-2019), Portugal must progress sufficiently to meet the debt reduction benchmark at the end of that period (the excess over 60% of the public debt has to be reduced by at least 5% each year, on average, over three years). For this purpose, structural adjustment should reach 0.7 p.p. in 2017, and 1.1 p.p. in 2018 … The aim to comply with this list of budgetary rules influenced necessarily the budgetary outturn in 2017.

So if anyone was absent enough to think that the austerity bias was terminated in Portugal the reality should jolt them very firmly awake.

It is clear that the brief period that the Government allowed some fiscal latitude to support growth is over and that the

fiscal strategy is best understood to “be considered a restrictive countercyclical policy”.

The Government is now in lock-step with the “European budgetary rules inscribed in the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and

Union” and this:

… Portuguese policy reorientation means that the government has assumed harder external restrictions on its own discretionary fiscal policies and therefore on its own capacity to follow expansionary fiscal policies.

Hardly a progressive utopia that some Europhile Leftists have been holding out.

Conclusion

The EuroMemo paper says that the Portuguese government clearly attempted to row against the European stream in 2016:

… where supply-side economic policies predominate and wages are essentially considered as production costs. With this form of “doing differently,” the government has given again precedence to the citizens and has been able to relieve social tensions as well as the feeling of uncertainty that lingered among the Portuguese people.

But while that has led to “the improvement of economic expectations” and fostered further hopes:

the Portuguese are expecting an increase in wages and the improvement of professional careers, in the public sector, as well as labour law changes in order to reduce job insecurity, to promote collective labour agreements and to eliminate the bank of individual labour hours, in the private sector.

The problem is that the pressure now to conform with the SGP rules is making it impossible to realise these heightened expectations.

The job was really only started in 2016 and there would have to be significant fiscal expansion to resolve all the damage that the austerity period caused.

The conflict between the Government’s aspirations “to direct fiscal policy along its own path, different from the one that is proposed by the European institutions” and its desire to also “comply with European budgetary rules” is unresolvable.

The EuroMemo paper concludes that:

The Portuguese fiscal policy in 2016 may be judged as a government political triumph over the European institutions, in the sense that it questioned some of their economic policy guidelines and economic forecasts, even having narrow leeway, taking into account the European budgetary rules. However, the Portuguese fiscal policy since 2017 seems to be a political triumph for the European institutions, since the government, on facing the trade-off between reducing public debt according to the European budgetary rules and meeting the Portuguese citizen’s expectations, has chosen the former.

And the “permanent loser” in all of this?:

… the collective choices of the Portuguese who rejected, in the October 2015 legislative elections, the austerity policies and trusted in the current government to reverse the direction of the fiscalpolicy.

The recent ‘experiment’ has demonstrated that:

… member-states leeway to use the state budget as an instrument of demand-side expansionary policy through expenditure increase is too narrow in the SGP context.

Fiscal policy under the monetary union has been “transformed from a policy instrument to an objective-indicator of economic policy”, which means that the Eurozone authorities have lost an understanding of what fiscal policy is for.

It is not to achieve some pre-ordained level or threshold. The economy should not have to adjust to some rigid fiscal rule or target.

The fiscal balance should adjust always to the needs – social and economic – of the society.

The Europhile Left should study the Portuguese situation closely. It is not the wonderland some of them have held it out to be.

True flexibility will only come with exit! That should be the goal of all current Member States. Get out and

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

That is, sadly, an extremely hard thing to explain to leftists in Portugal, as they’re elated about the change in course from years of wage and pension cuts. Meanwhile, speculative rents keep increasing and eliding many gains, while moving outside the big cities overloads roads and the disappearing public transit system. No-term contracts increased, but they’re incredibly precarious with the government having transformed some non-protections from abuses into others that should be about as effective.

I’ve also come to know some stories about the state of the public hospitals, and I’m amazed they still cure someone – no CT scans for early stage pancreatic cancer for at least 4 months, with the attending doctor pretending not to be there so he would give no answers; a complete mess of medical data records leaving (private, of course) GDPR consultants telling doctors they should effectively stop trying to help rare disease patients. The whole lot of Ecofin members, at the very least, are murderers, plain and simple.

Unfortunately, PS is full of pure Brussels fetishists dreaming of a cushy placement, BE burgoisied and believes DiEM while focusing on identity politics, and the communists got tired of being called an “old tape” and are fairly content with the status quo, while the xenophobic allied with the extreme neo-liberals keep getting airtime thanks to public prosecutors on a crusade against the former PS prime-minister – warning media of arrests, leaking recordings of interrogations, leaking wild corruption scenarios and extending the investigation well beyond a reasonable time frame.

It can only get much worse before getting better, but it is definitely a poster child for the EU.

Thank you very much for your sober analysis of the Portuguese current situation. In fact, while some limited gains have been achieved over the last three years (e.g., regarding pension cuts), no significant turn from austerity has occurred. The most important political and economic problems of Portugal remain unresolved, namely those resulting from its peripheral role within the European Union. That was not expected to be otherwise – the governing party (“Socialist” Party) is perhaps the most Europhile Portuguese party and has never really abandoned third-way neoliberalism; as such, the “Socialists” will always choose compromise with Brussels over adoption of an anti-austerity policy. Regarding the two other parties supporting the “Socialists”, the Left Bloc is adopting an ambiguous stance on the EU, while the Portuguese Communist Party has long been the party most vocally opposed to the European neoliberal project – its predictions in the 1990s regarding the consequences resulting from the adoption of the Euro turned out to be pretty accurate.

Unfortunately, in Portugal, a serious discussion of European issues is practically absent from the media and from the political debate – the two major parties (the “Socialists” and the right-wing parties) prefer to discuss faits divers and ignore the “elephant in the room”; the Europhile Left is magically waiting for the EU to abandon its neoliberal stance and become a progressive force; and the media mostly portrays the EU in a simplistic and superficial way as “a force for good”.

Bernardo says:

‘Unfortunately, in Portugal, a serious discussion of European issues is practically absent from the media and from the political debate – the two major parties (the “Socialists” and the right-wing parties) prefer to discuss faits divers and ignore the “elephant in the room”; the Europhile Left is magically waiting for the EU to abandon its neoliberal stance and become a progressive force; and the media mostly portrays the EU in a simplistic and superficial way as “a force for good”‘.

Eerily familiar.

It strikes me that that elegantly-phrased description could equally-well apply, almost word-for-word, to most EZ member-states (it definitely does to the one I live in). “Sleepwalking” would be another way to describe it.

Bill:- “The Europhile Left should study the Portuguese situation closely. It is not the wonderland some of them have held it out to be. True flexibility will only come with exit!”

But they won’t, because that would force them to face the fact that they’ve been utterly, abysmally, wrong all along. They don’t have the intestinal fortitude necessary for abandoning groupthink.

At least the Portuguese left had that, even though they’ve now become transfixed in the headlights of the oncoming EU juggernaut. It’s almost as painful for a sympathetic spectator to behold as being forced to witness the Greek tragedy has been.

If only the Italians can hold their nerve there might be hope: Portugal is too small to do the job on its own.