Last week, I wrote about - The decline of economics education at our universities (February…

Exploring the effectiveness of social media

Regular readers will know that I have become interested in the concept of messaging and language to help in the practical goal of widening the spread of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) knowledge and putting really powerful tools into the hands of activists who build social and political movements. There are some great efforts underway (for example, Real Progressives in the US). On October 5, 2018, I will be launching the Gower Initiative for Modern Monetary Studies and running some workshops for them in London. This is another excellent activist group setting out and prepared to climb the hill and all the mainstream economics obstacles that are in their way. The aim is to build a network of these groups around the Globe (Italy, where there is already a solid network; Spain, similar; Germany – I will be there October 13); Finland, already solid activity; Scotland, I will be there October 10; Ireland, I will be there October 3-4, and elsewhere). On this theme, some current research, which Dr Louisa Connors and myself will unveil at the The Second International Conference of Modern Monetary Theory (New York, September 28-30), is the role that social media (among other things) plays in spreading knowledge. Regular readers will know I occasionally point to what I see as the futility of twitter firestorms where some MMT activists interact with some neanderthal-economics type who can’t get Zimbabwe typed quick enough and a drawn out back-and-forth of tweets, which can sometimes go for days, with increasing numbers of twitter addresses copied into the thread. They usually end in grief. The question is whether these social media platforms are suitable given what we know about effective framing and the type of language and strategy that is necessary to make that framing persuasive.

In this blog post – There is a true oppositional Left forming and gaining political traction (June 21, 2017) – I analysed the most recent British General Election which was held on June 8, 2017.

At that election, Labour won 262 seats (up 30) and took 40 per cent of vote (up 9.6 points). The result was a near-miss for the ruling Tories who thought they would smash Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, especially after the Labour leader had been subjected to a long-running and dirty campaign of treason by the Blairites within the Parliamentary wing who couldn’t stand the thought of their dismal legacy fading into the gutters where it belongs.

The mainstream media, including the so-called progressive mastheads, in the UK had backed the Blairites to the hilt with a continual stream of ridiculous articles and Op Ed (led by characters such as Nick Cohen in the UK Guardian).

Cohen even claimed that the Tories would take a glorious victory and May would (Source):

… never have risked an early election if Labour had competent leaders who had not alienated millions of voters.

He predicted that Corbyn “must resign” and that “would have a purifying effect and a new opposition would be born from the ruins”.

He disclosed himself as an opinionated nobody during that period (if there was ever any doubt).

Corbyn got closer than anybody ever imagined by running on a very progressive program, which mostly jettisoned the Blairite past.

I concluded in the blog post that, despite having an undeveloped progressive macroeconomic narrative, Jeremy Corbyn has created a true opposition Left force in British politics – a space that the Labour Party abandoned in the 1970s, when it adopted a Monetarist stance.

His “for the many not the few” mission statement resonates with the feelings of people, who have been denied by neo-liberalism’s attack on government services and the more recent austerity.

Corbyn has attracted thousands back into the Labour Party membership ranks because his popularity as a person and as a leader with a resonating message.

The question that was of interest is how could he have pulled that off when the mainstream media was firmly, no vehemently, against him?

It used to be said in Australian politics for example, that we could get a very good feel for who would win a federal election by what the News Limited editorial said in the week of the election, such was the influence of the major newspaper mastheads in the past.

The same goes for Britain – in the past.

But the British election revealed that the domination of the mainstream press is now in decline.

The YouGov summary breakdown (June 13, 2017) – How Britain voted at the 2017 general election – tells us that Corbyn’s Labour Party dominated the vote for all age groups up to 40-49.

Labour was very dominant among the younger voters – 18 to 29 year olds.

We also learn that far from being turned off by politics the majority of eligible younger British voters actually voted.

First, younger voters have no life experience with old Labour (pre Thatcher). So all the bad things that New Labour-ites and the Tories might have said about Corbyn’s Labour would have had no meaning to them.

What do they care about the Winter of Discontent, Harold Wilson’s exchange rate crises, the bullying trade unions and all the rest of the narratives that are wheeled out to degrade the image of Labour – especially Corbyn’s ‘blast from the past’ policies (as depicted by the Tories and Blairites)?

What young people are searching for is hope for the future. And they have determined that neo-liberalism is not a source of optimism for the future.

The mission statement – “for the many not the few” – resonates in that regard.

Neo-liberalism and austerity has blighted their educational opportunities, undermined their health system, created chaos in the privatised transport system, among other things.

It is a mean and nasty mission statement. That doesn’t resonate.

Second, while the mainstream media pumped out daily bile attacks about Corbyn, the young people don’t really buy or read the newspapers anymore.

The young people, increasingly connected by social media, and that is making all the Murdoch and Guardian-type hysterics irrelevant.

Which means that learning about how social media can assist or hinder framing is important for MMT activists.

Regular readers will be aware of work I have done with Dr Louisa Connors in this field.

For example:

1. Framing Modern Monetary Theory (December 5, 2013).

2. The role of literary fiction in perpetuating neo-liberal economic myths – Part 1 (September 11, 2017).

3. The role of literary fiction in perpetuating neo-liberal economic myths – Part 2 (September 12, 2017).

4. The ‘truth sandwich’ and the impacts of neoliberalism (June 19, 2018).

Our first refereed journal article together in this project (many more to come) came out last year in the Journal of Post Keynesian Economics – Framing Modern Monetary Theory (June 14, 2017).

That literature makes it clear that the way we frame our arguments and the language and vocabularies that we deploy is highly significant in whether our views are accepted or not in the public discourse.

It also sets out a strategic path which allows us to understand how neoliberalism has permeated every area of our life and is so resistant to opposition, even when the material outcomes that are associated with it are so poor.

What we argued in that paper was that a strategy must begin with a narrative rather than facts.

The “for the many not the few” is a narrative – it is a general statement.

Clearly, we want to instill in the public debate a sense that the government is there to advance social purpose and that purpose should be articulated and narrated in ways that will resonate with and activate the frames in our brains that constrain the way we interpret information.

That exercise should pre-date the presentation of the facts or evidence.

We used the example of the New Zealand Mayors Task for Jobs which some years ago ran its campaigning for funds and policy changes using the mission statement – “Working towards the ‘zero waste’ of New Zealanders” and “Our Youth, Our Future”.

The smart strategy then connects these general goals to associated concrete actions.

So as an example, the mission statement – ‘Jobs for all that want to work’ – is almost universally desirable. But the framing exercise has to go beyond that to attack an action.

So we might say that to have ‘jobs for all’ the government has to ensure aggregate spending rises by x per cent in order to create y million jobs and it can only do that if the fiscal balance moves in harmony with the non-government sector spending and saving plans and action.

In this way, we invoke so-called invoke event-causation structures to force the debate to move beyond generalities such as ‘free markets will grow the economy and create jobs’.

We then clearly have to articulate why mass unemployment occurs and how it will not cure itself naturally. Further, by implicating the government as part of the solution they have to counter such claims that governments do not create jobs by detailing public employment initiatives that clearly create productive work.

We then drill down to lower level statements such as the government chooses the unemployment rate.

How do we learn that?

By building an understanding that a currency-issuing government can always purchase whatever is for sale in its own currency, including all idle labour.

If there is a jobs shortage, then we know spending is deficient overall. So given the executed spending plans of the non-government sector leave total spending short of what is required, the only solution, at that point in time, is to immediately increase government net spending.

Messaging is about how we use words.

What we learn from the work of cognitive scientist George Lakoff, is that words have no meaning outside of the frames, which are metaphors and conceptual frameworks that we deploy to make sense of the real world around us.

They don’t necessarily define ‘reality’ in general. But, rather, they define our reality, which may be a different matter altogether.

This is especially the point in the case of macroeconomics, a point I continually point out.

The metaphors that neoliberalism deploys to advance its economics narrative rely on a system of connected myths for their ‘authority’.

When a mainstream economist claims that the government will run out of money they are not saying anything about reality in a currency-issuing state. Rather, they are constructing a false reality which serves the ideological agenda they are pushing.

So when we hear or read words we interpret them within the frames we operate with at any point in time.

George Lakoff wrote in his 2010 article in Environmental Communication – Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment – that:

All of our knowledge makes use of frames, and every word is defined through the frames it neurally activates. All thinking and talking involves ‘framing.’ And since frames come in systems, a single word typically activates not only its defining frame, but also much of the system its defining frame is in …

Since political ideologies are, of course, characterized by systems of frames, ideological language will activate that ideological system. Since the synapses in neural circuits are made stronger the more they are activated, the repetition of ideological language will strengthen the circuits for that ideology in a hearer’s brain. And since language that is repeated very often becomes ‘normally used’ language, ideological language repeated often enough can become ‘normal language’ but still activate that ideology unconsciously in the brains of citizens*and journalists.

The question this is not to avoid ‘frames’ but “whose frames are being activated*and hence strengthened*in the brains of the public”.

Some guidelines follow:

1. “Introducing new language is not always possible. The new language must make sense in terms of the existing system of frames. It must work emotionally. And it must be introduced in a communication system that allows for sufficient spread over the population, sufficient repetition, and sufficient trust in the messengers.”

2. “negating a frame just activates the frame”.

What is this about facts?

Lakoff’s work indicates clearly why just telling the “people the facts” and “they will reason to the right conclusion” is a flawed approach to political persuasion.

We do not reason or think rationally (as per the concept of Enlightenment reason).

Lakoff tells us that the “old view” that “reason is conscious, unemotional, logical, abstract, universal, and imagined concepts and language as able to fit the world directly” is false.

Most of our reasoning about our reality is “unconscious” and emotional and is rendered logical by the frames we deploy.

The point is that:

… the facts must make sense in terms of their system of frames, or they will be ignored. The facts, to be communicated, must be framed properly. Furthermore, to understand something complex, a person must have a system of frames in place that can make sense of the facts.

Effective communication is about the use of words to activate desired frames.

So a prior task is to be constructing this set of desired frames and in macroeconomics we are up against a very powerful, existing set of frames that are difficult to shift, given the way they have penetrated our emotional psyche.

George Lakoff asks a relevant question in this context: “Have you ever wondered why conservatives can communicate easily in a few words, while liberals take paragraphs?”

This question, also relates, in part, to those who criticise my blog posts for being too long!

The answer he gives is “that conservatives have spent decades, day after day building up frames in people’s brains, and building a better communication system to get their ideas out in public.”

The government is just a large household budget analogy is an example. That is so ingrained that conservatives (and flawed progressives) can quickly call it up without short, pithy messages.

But for a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) developer such as yours truly the problem is that I have to build a frame before I can pump out the message.

So if I was just to say that a sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency, while true in reality, that makes no sense to many people because there is no system of frames built for people to interpret those words correctly.

My statement ‘sounds like’ something they have heard before – such as governments spending like a drunken sailor (example) – and the neoliberal frame is activated.

George Lakoff uses a climate change example to show how words and slogans (facts) have little impact if in the “absence of a system of frames”.

So the challenge is to “to talk about values, not just facts and figures; to use simple language, not technical terms; and to appeal to emotions.”

The prior challenge though is that “people have in their brain circuitry the wrong frames for understanding” the reality they are in.

This is very apposite in the case of macroeconomics as our earlier work demonstrated.

George Lakoff considers this problem means that people:

… have frames that would either contradict the right frames or lead them to ignore the relevant facts. Those wrong frames don’t go away. You can’t just present the relevant facts and have everyone erase significant circuitry in their brains. Brains don’t work that way. What is needed is a constant effort to build up the background frames needed to understand the crisis, while building up neural circuitry to inhibit the wrong frames. That is anything but a simple, short-term job to be done by a few words or slogans.

That is why my blog posts are repetitive, thorough, and relentless. I took it on myself to try to shift that brain circuitry in my readership – slowly, over and over and over, for as long as I can.

I knew that it would take many years to see change. My other original MMT colleagues, I think, we more optimistic as to the time frame. In part, that was cultural. Australians are somewhat less ‘out there’ than Americans, for example. But my reticence was driven by the ideas that Lakoff espouses in the quoted passage above.

There is so much groundwork that is required.

Lakoff talks about the political challenge and one huge issue for MMTers is what he calls the “Let-the-Market-Decide ideology” which the ‘free market’ is seen as a natural process and capable of moral arbitration.

I have written about this a lot in the past.

The market rewards ‘sacrifice’ and punished wilfulness and indolence. So it is easy to slip from that frame into statements about the unemployed being lazy and unwilling to sacrifice for their families etc.

This ideology continually reinforces the idea that the natural process can become sick if government forces it to do ‘unnatural things’ such as pay minimum wages or income support payments.

And so it goes.

This is a massive challenge for a body of economic thought that places the capacities and responsibilities of the currency-issuing government at the centre of the analysis.

These are the considerations that we are taking into account as we embark on research on messaging and the media.

An effective media strategy has to begin with the development of progressive short-term and long-term frames.

These have to be case “in terms of moral values” which are clearly distinguishable from any policies we advocated.

Lakoff says we have to “Always go on offense, never defense” which means we should:

Never accept the right’s frames – don’t negate them, or repeat them, or structure your arguments to counter them. That just activates their frames in the brain and helps them.

I discussed that issue in this blog post – The ‘truth sandwich’ and the impacts of neoliberalism (June 19, 2018).

He also says that “laundry lists” (of things to do) are deficient and a “structured understanding” is required. Hence my blog posts are longer than most and I try to track through an argument in a structured way so the knowledge is provided and the application of that knowledge clearly demonstrated.

Whether I succeed is another matter.

He repeats the warning:

Don’t just give numbers and material facts without framing them so their overall significance can be understood. Instead find general themes or narratives that incorporate the points you need to make.

What has all that to do with social media?

The use of social network has been an important part of the development of MMT awareness on a global scale.

I recall a meeting that a few of the original MMT team had some 15 years ago where I blithely announced that I was going to start a blog because I assessed that our message, which up until then was mainly manifested in academic papers and conference appearances, was not gaining traction in the wider audience.

My colleagues looked at me as if I was from the planet Mars.

Not to be discouraged I went ahead and the product of that decision is fairly obvious now. Over time, the original MMT team have all embraced social media in one way or another, some more successfully, some more frenetically, and this is been a significant way in which our ideas have started to gain wider appreciation.

While the patterns of use of the different social media instruments have evolved over time, as new communication modes have entered the scene, and demographic use has varied, it is clear that MMT is all over the Internet as a result.

Originally Twitter and Facebook were the most popular by far but they have been in decline for some years now, particularly among the teenage users. The latter group prefer Instagram and, overwhelmingly, Snapchat.

But Twitter is still very much in vogue among older users and is particularly prominent in economic policy discussions.

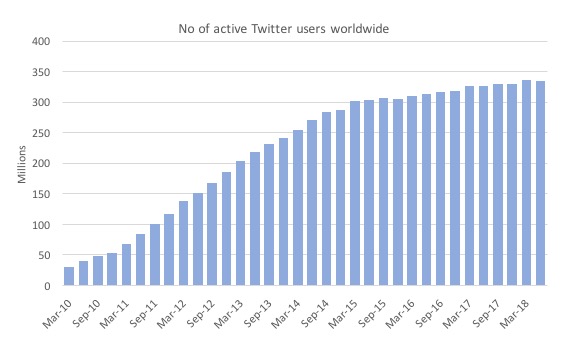

The following graph shows the number of active Twitter users worldwide (in millions). So even though the rate of growth in this user base has slowed dramatically the absolute number of users continues to grow.

In thinking about the sort of considerations I discussed above, the question we became interested in is whether Twitter is an effective vehicle for promoting MMT awareness and political change.

Many Twitter exchanges are just what we might call – fact duels.

So an MMT proponent quotes a fact that supports the body of propositions they have learned about MMT and some neanderthal tweets back – past them – about some other fact and so it goes.

These twitter firestorms get nowhere and often end up in a dead-end of ad hominen.

So if we know that the choice of words is important and that there must be a framework for them to activate can Twitter be an effective instrument for paradigmic change?

That is what we are currently researching and we will have more to say in New York (and via my blog posts before that) as my Python code extracts more data and we analyse it.

But there is an extant literature on related issues.

Is Twitter an effective vehicle for social change?

There was an interesting study published in the Computers in Human Behaviour journal (66, 2017, 179-190) by Ben Wasike (an academic from the University of Texas) entitled – Persuasion in 140 characters: Testing issue framing, persuasion and credibility via Twitter and online news articles in the gun control debate (you need library access, sorry).

The aim of the study was to:

1. “examine how partisan activists in the post Sandy Hook gun debate framed their arguments and how these framing patterns affected persuasion and credibility.”

2. examine “the effect of the medium of transmission of the said arguments (Twitter and online news articles) and how that affects persuasion and credibility.”

The specific hypotheses:

A) Whether framing the gun debate as a crime and gun safety issue has a different effect on persuasion and credibility than when framing it as a gun rights issue;

B) Whether these framing effects are more or less profound when the issue is presented via Twitter or via online news articles.

While the issue examined in this research paper was gun control in the US, which some might think is a different type of topic to economic debates, the commonality is the fact that both debates are largely driven by entrenched beliefs where the dominant position is evidence poor and supported by a massive commercial lobby that throws millions of dollars at politicians to maintain their position.

So there might be some lessons to learn from this study.

Lets see.

The paper begins by noting that “social media uniquely persuades and changes behavior and attitudes be it political, health or consumer-related” and gives appropriate examples (and references).

I will leave it to you to follow through if interested.

The extant literature has indicated that “Facebook and Twitter positively affect citizen attitudes towards the government because they foster a more efficient communication environment … and transparency”.

In terms of the gun debate, the question is whether:

There is a statistically significant difference between the persuasiveness of crime and gun safety frames and that of gun rights frames on Twitter.

And does the choice of media – “Twitter and online news articles” – which adopt different types of framing “affect the persuasiveness of the gun debate arguments and propositions”?

The literature tells us that traditional media frames issues differently to social media.

For example, during the Arab Spring, the traditional newspapers “framed the uprising in terms of national security and economic consequence frames while Twitter users framed it terms of human interest frames while emphasizing freedom and social justice”.

The other issue relates to “credibility” which means that “In order to persuade and change perceptions, issue framers first have to gain the trust of their audiences and subsequently gain believability”.

In other words, the way frames are presented on Twitter, impact on whether the readers will have credence in them and the authority of the tweeter.

The study used what is called a 2 x 2 x 4 experimental design to explore these questions so they contrasted:

1. Twitter versus online news articles.

2. Issue framing – whether there was a difference between an “expanded background checks vs. the assault weapons ban” frame.

3. Issue stance – “whether the argument was for or against the four issue frames at hand (Pro-background checks, anti- background checks, pro-assault weapons ban and anti-assault weapons ban)”.

I won’t discuss the way they set up the experiment so that I can just cut to the conclusion. 92 per cent of the cohort tested use social media (compared to 76 per cent for the Nation as a whole).

The conclusions of the study were:

1. “crime and gun safety frames were more persuasive than gun rights frames”.

2. “pro-background checks arguments were the most persuasive and anti-background checks arguments the least persuasive”.

3. “frames transmitted via news articles … were more persuasive than those transmitted via Twitter”.

4. “Within these two media formats, crime and safety frames were still more persuasive than gun rights frames”.

5. “a pro-gun control source … was viewed as being more credible than an anti-gun control source … a source framing the debate as crime and gun safety argument was viewed as being more trustworthy, believable and sincerer than one framing arguments based on a gun rights argument.”

6. “The least credible source was one framing an anti-assault weapons ban message via Twitter.”

7. Importantly, “Data analyses show that news articles drove persuasion more than Twitter. This however does not mean that Twitter is not an appropriate medium of persuasion”.

8. “Extant research also shows that sources who display veracity in terms of competence, trustworthiness and goodwill tend to receive more credibility”.

Conclusion

So a lot to consider.

At this stage, my conclusions are that Twitter needs to be handled very carefully if it is to be thought of as a key media instrument in pushing change in economic awareness.

As I suspected, this research shows that Twitter firestorms are unlikely to be very helpful. They come up against credibility issues and framing persistence.

A shoot-out of facts is not likely to be very persuasive and could well reinforce the opposite.

Politeness seems to be an important ingredient in establishing credibility. So Tweets that call someone a dunce (or worse) are to be discouraged.

Long drawn out debates on Twitter are unlikely to be persuasive.

Blog posts – the more traditional approach seem to be more effective vehicles for persuasion.

Our research goes on.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Couldn’t agree more on the importance of the internet in spreading counter-establishment narratives. What you argued about Corbyn was true of Sanders in the US as well, as I wrote about here: https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2016/05/where-did-the-bernie-sanders-movement-come-from-the-internet.html

I agree that politeness is extremely important in these social media exchanges.

I do wonder about the idea of Twitter exchanges being unhelpful though. After all, it is not simply about the people involved in the conversation; others are quietly watching the debate who could be being persuaded.

Has any work been done on this? I can’t even see how it could be.

A very useful post, Bill. But you don’t mention the two aspects I consider are the most inhibitive to spreading the word.

SPREAD ITSELF. Getting the word out to the maximum number of people. And the problem is that few have any interest in macroeconomics (maybe that very word needs framing). I rarely speak to anyone who does not adopt a glazy-eyed look as soon as you mention it. Even the leader of a small political party in the UK who I met for lunch admitted he had no interest in economics nor any understanding of it, nor did he wish to. Mind you, I’m still working on him. So the word, even though the spread is growing, is only a very tiny proportion of the population, and most who happen upon it will just delete it and move on.

FUNDING. The UK Conservative Party spent £18.5 million on the 2017 election. And that’s just a part of their overall funding. Even a certain group in the UK who shall be nameless but who campaign for monetary reform (on the wrong premise, unfortunately) must get considerable funding if they can afford full time staff one of whom is their chief economist. I understand that they are supported by the Quakers. To my knowledge nobody donates to the MMT cause. I asked Warren and he said nobody does.

I am very much looking forward to the GIMMS launch and hope that these issues will be addressed.

“Have you ever wondered why conservatives can communicate easily in a few words, while liberals take paragraphs?”

This is a fundamental point. People like me, stumbling upon MMT (luckily!) during the early years of my desperate attempts to learn about economics seem to have gone through and ‘evangelical’ phase where one banks out phrases like ‘Taxes don’t fund spending’ and ‘the Government is not financially constrained’. Eventually, I learned this did not work and that starting from the point of view of the perceptions of others was better. This means improving one’s understanding ( I’m glad Bill’s posts are ‘repetitive’ in this respect – I’ve been shocked at how many times I need to re-read things!) and using words that link with the perceptions and place you interlocutor is in.

In the UK, I’ve found it useful to refer to inequality, the housing/land asset bubble and private debt as a good link as well as pointing out how the Thatcher ideology (house-owning nation, trickle down, share-owning nation) has not only not happened bu we have its diametrical opposite. After this I find one can make some inroads about deficits and ‘the golden age of capitalism’ and how debt to GDP was 200% in 1945 etc…The biggest problem is that, in the UK, there is a significant body of people who have ‘done well’ out of the last 40 years (property owning, financial assets) who cannot see beyond the end of their noses and will not abandon their framing because they perceive it as working well for them.

As an amateur, my main problem is making elementary mistakes myself and dealing with cognitive challenges but it’s important to keep the learning going. Bill’s blog serves this purpose well.

I have been engaging on the internet for 5 years now. There is a great forum called QUORA that regularly asks questions about economics, usually framed in queries about government debt and other mainstream narratives that are troubling people. The neo liberal idea of making economics unsettling and worrisome is quite obvious here. I have to address the existing frame but concentrate on reality and its consequences. It seems to be working although the same questions repeat too often.

Lakoff’s point 2 is very pertinent. so i try to avoid reinforcing the existing narrative if possible.

Sometimes I get into a spat as my understanding of banking is not deep but generally I can hold my own.

Some other respondents understand some parts of MMT and write in support monetary sovereignty in particular.

Lee Camp seems to make an effective use of twitter. He stays on a progressive and MMT type message with hard hitting but respectful comments that resonate with many of the problems people are having with the neoliberal mantra. For example:

Lee Camp [Redacted]

@LeeCamp

GOOD NEWS, for a change: Activists in Baltimore were able to stop their water supply from being privatized. This is a HUGE deal and a battle that will continue around American cities for as long as there is profit to be made in poisoning our water.

“long-running and dirty campaign of treason by the Blairites within the Parliamentary wing who couldn’t stand the thought of their dismal legacy fading into the gutters where it belongs”: you’ll love this. Hodges, in a recent interview, said that Labour’s problem wasn’t anti-semitism. *He* (Corbyn) was the problem. She repeated this statement to the interviewer in a rather emphatic, possibly hysterical, manner to the interviewer. She looked as though she was going to break down as she was interviewed. There are indications that some of them have become irrational. When you hear things like, “I would rather lose an election than have to give up my principles”, you have to wonder. Especially when the principles themselves are never mentioned.

Jeremy Corbin got close in UK election because anti-Brexit voters had nowhere to go. I understand that Brexit could work if a government was elected that more closely took the concerns of everyone into account. Labour and Jeremy Corbin often use neoliberal speak to explain their positions.

The views that you express regarding MMT answer questions that I have had since university 45 years ago. Without Facebook and Twitter I would not of known of theses ideas. An all of the above approach works to educate because we all learn differently.

Like Simon Cohen, I’m a novice trying to spread the fundamentals of MMT through The Economist & its Open Future venues. I’ve also redone an old website – TENonline.org – trying to convey a simpler understanding of those fundamentals. Any comments (pro or con) would be welcome.

Peter, like your book title with its allusion to one of Kant’s seminal propositions: Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made (my favorite translation), and your expansion of it. It does look as though your approach complements that of Bill’s well. A nice synergy.

After the 2017 election result was clear, a shocked Theresa May gave a speech outside 10 Downing Street that actually used the phrase for the many not the few’ or something very close to it. I think the shock of the result caused her to use that expression out of sheer desperation and here own vacuity.

Of course, there was nothing behind it just here own neural network lunging for the first thing to hand.

I quite like the Real Democracy Party’s framing.

“Would you allow an estimated 2.9 million, (13.3%) of Aussies, including 731,000 children aged below 15, (17.4%) to continue to live below the poverty line.

Would you still wait patiently for the “trickle down market” to create enough jobs to employ the unemployed – and provide more work for the most casualized work-force in the world – who want more work?

Would you still be OK with victims of domestic violence being forced to sleep in cars with their children?

Would you still be happy to have a family’s wealth determine how well the children do at school, what or whether they can study at university or TAFE?

Would you still be happy to have a family’s wealth determine their access to quality health care when needed?

Would you continue to privatise as many government owned monopolies as possible and be happy to watch service go down and prices go up?

Would you continue to reduce investment in developing renewable energy technology?

Would you carry on permitting corporations to damage the environment and add to global warming in pursuit of profits?

Would you be prepared to tell households and business that they just have to live with slowing Internet speeds, inadequate public transport and massive traffic jams?

Would you fund all political groups for their election campaigns rather than allowing them to get donations?”

https://www.realdemocracyparty.net/Policy/Economy/

If MMT wants to communicate to the general populace in order to win the day for abundance instead of austerity they will need to explain it in as simple a fashion as possible. In the end everything is political after all.

This is a great piece.

George Lakoff. I will look into his work.

It makes sense. It explains why people can be quite stubborn.

Thanks Larry; sadly, the publisher thought the title was too abstruse, and disagreed that it would generate sales from people mistaking it for a Harry Potter book 😉

It seems that most people are on board with every who wants to work getting a job, some would remove the willingness prerequisite.

The basic aim of the Job Guarantee is not so hard a sell except to right wing government haters and left wingers who just hear work for the dole.

I think very few people realise that the prevelant high rates of unemployment (>2%) result from deliberate policy by the government and reserve bank. Monetarism is extremely poorly understood and I am not sure Bill’s academic discussions really sheet home the sheer viciousness of maintaining a buffer stock of unemployables. I think the point that politicians are serious when they say we are currently near “full employment” is probably the real chink in the neoliberal framing armour.

Please don’t forget the power of a good image (photo, cartoon, chart, graphic, video link etc) to grab the attention of readers. When one posts a link to an article on Facebook for example, the algorithims automatically select the uppermost image which may often be unsuitable or often there isn’t an image – which usually applies to Bill’s blog posts.