I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

The decline of economics education at our universities

Economics courses at university in Australia have been under threat for several decades now and many specialist degrees have been abandoned by universities as student enrolments declined. When the federal government merged the vocational higher education institutions (Colleges of Advanced Education) with the universities in the late 1980s, traditional economics faculties were swamped with half-baked ‘business’ courses in management, HRM, marketing and whatever which then attracted the aspiring ‘entrepreneurs’ who were told by the marketing literature that they would be fast-tracking into management careers in the corporate sector. The reality was that these programs did not equip the students to do very much at all (perhaps erect marketing displays in supermarkets!) but the impact on economics programs was devastating. The most recent Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Bulletin published on January 30, 2025 contained an article which bears on this issue – Where Have All the Economics Students Gone?. I discuss some of the implications of the decline in student numbers in economics and the lack of diversity that existing programs have for societal well-being.

A short history

In 1994, I was elected by my colleagues to be the next Head of Department of Economics at the University of Newcastle.

It was still a time when ‘democracy’ ruled in Australian university departments and I was actually the last elected head at that university.

The tides of neoliberalism and corporatisation were already beginning and during my term, consultants recommended that the university cease elections for all the senior positions (HOD, Deans, President of Senate, etc) and instead move to appointments only.

Obviously, this reduced the voice that we had as the appointments were crafted to maintain control of the new KPI-driven agenda.

I remember that after my first term (4 years), I was invited to continue for a second term by the Vice Chancellor.

At the meeting, he said ‘welcome, you are one of us now’!

I asked him who ‘us’ were and he replied part of line management.

I demurred and told him that he was wrong and that I was just the representative of the collective (my colleagues) to management and that he should not think otherwise.

I recall him being a bit surprised (-:

But those days were the beginning of a long decline for economics education in the university system.

Up to that time (1994), the federal government had allocated funding to States to fund capital and recurrent expenditure in universities on a triennial basis.

The public universities in Australia are legislative creations of the states but it is the federal government money that kept them afloat.

The triennial funding system gave universities some security and continuity and departments were able to make pitches on the basis of the so-called ‘establishment’ (which carried a number of appointments).

The link between student load and the establishment was hazy and the latter was driven more by the political skills of the university admin and then within each institutions by the skills of the faculty bosses (Deans and HODs).

When I became HOD, the Economics Department was the largest (in staffing) in the university and the staff had enjoyed a lot of security for some years.

Things changed dramatically around that time though.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the federal government created a unified tertiary system – merging the universities, institutes of technology and colleges of advanced education.

It was brutal shift and caused massive disruption to the internal structures of the universities.

Overnight, we had university academics with PhDs who had built research careers forced to work with CAE staff who were really school teachers – no advanced degrees, no research background and used to long holidays over Summer (which is the time the active researchers write up their competitive research grant applications).

The mergers created ‘business schools’ and downgraded the position of economics – which was seen as a service course for these new ‘business degrees’, rather than the core academic discipline of the traditional faculties.

I recall getting memos from senior managers demanding to know why the first year failure rates, which were always around 30 per cent, were not like the near 100 percent pass rates in management.

The emphasis was on why we were bad rather than why the 100 per cent pass rates were bad and avoided the fact that students in management were given easy exams which almost anyone could pass with little understanding of anything.

But things became much worse soon after.

The federal government, as part of its unified tertiary system, abandoned the triennial funding arrangement and instead introduced the ‘relative funding’ model, which provided a single operating grant to institutions based on student load.

Extra funding was provided – so-called ‘research quantum’ – on the basis of research output.

Within institutions, the relative funding model provided $s to disciplines based on enrolments which meant that the old concept of an establishment profile was abandoned and the cold winds of ‘load’ became the source of funds and staffing.

There were many distortions in teaching and research that followed – short-termism, load rather than quality, etc – which I won’t go into here in any detail.

But the rush was then on to pack the rafters with students.

Also the ‘export market’ opened up and overseas students were seen as the way to ease funding shortfalls.

Further quality distortions accompanied that ‘gold rush’ which persist to now.

But in my first meeting with the Dean after taking on the HOD role I was told that the new relative funding model meant our Department budget had to lose about $A2 million in what was only a $4.5 million total annual allocation.

The reason – student load had diminished as the ‘business degrees’ entered the fray and economics was not seen as a desirable course of study.

In my time as HOD, the Department shrunk from around 32 full-time staff to around 14 – approximately (I have no formal records to be exact) through various attrition programs pursued by the Dean.

After my second term, the new managers of the Faculty forced a closure of the Department altogether and the abandonment of the Economics degree.

At that time, I negotiated with the Vice Chancellor to leave the Faculty structure and to shift my research group – Centre of Full Employment and Equity – as a stand-alone entity within the University structure and only report to the DVC Research.

I was able to do that because I was attracting a significant amount of external research funding which meant I could fund my group without faculty support.

It was very liberating but the plight of the economists within the faculty just deteriorated further because the majority of the research income generated by ‘economists’ went with me to CofFEE.

Anyway, the point of all that is that the decline in student interest in economics had had huge impacts across Australian universities.

RBA research

The RBA article (cited in the Introduction) notes that:

The size and diversity of the economics student population has declined sharply since the early 1990s, raising concerns about economic literacy in society and the long-term health of the economics discipline.

The RBA notes that economics was “one of the most popular subjects in high school three decades ago”.

But that has changed dramatically since the 1990s.

UAC is the Universities Admissions Centre and the RBA research examines data for just NSW and the ACT.

However, the trends they detect are national.

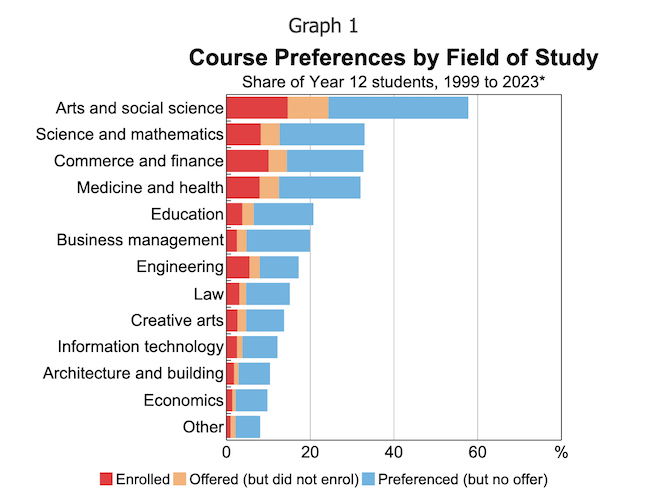

The following graph (Graph 1 in the RBA report) shows that “Between 1999 and 2023, only around 10 per cent of all Year 12 students included an economics course among their preferences to UAC, with just 1 per cent of all students actually enrolling in one”.

The decline since has not just been in overall numbers.

The RBA also finds that:

… there is a growing uniformity among economics students, and this also extends to those who become economists or apply economics in their careers

What do they mean?

Female students who studied Year 12 economics were less likely to include an economics course in their preferences than their male counterparts over the 1999–2023 period. Instead, female high school economics students were more likely to show interest in arts and social science, medicine and health, and law than their male peers.

Interestingly, of the females who initially express a preference with the UAC process for economics but “who ultimately chose not to enrol in an economics course had, on average, higher ATARs than males who enrolled in economics”.

The ATAR is the Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank – a score used by the admission centres to allocate students across university courses.

That means the academically brighter female students did not go into the economics programs, which are dominated by lower scoring males.

The other diversity angle is the students’ socio-economic background.

The RBA finds that:

… students who are interested in economics at university tend to belong to advantaged socio-economic groups, including students from non-government schools …

So the economics students are from the rich families and have attended the very expensive private secondary schools – which means they will have accumulated certain values about their ‘position’ in society.

I discussed elements of that tendency in these blog posts among others:

1. The conflicting role played by education in social mobility and class reinforcement (August 9, 2023).

2. The evidence from the sociologists against economic thinking is compelling (November 12, 2019).

3. The brainwashing of economics graduate students (February 12, 2019).

4. Economics curriculum is needed to work against selfishness and for altruism (September 19, 2018).

5. Education – a vehicle for class division (November 23, 2010).

A large body of research in social sciences (around the world) has demonstrated that standard economics programs at our universities breed people with sociopathological tendencies who elevate greed above empathy.

There is clearly some self-selection bias because the studies have never really isolated the impacts of the teaching programs from the tendencies of the students going into the programs.

One 2005 study that was published in the journal Human Relations – Personal Value Priorities of Economists – found that:

1. Economics students exhibited less altruism and more self-interest in their “first week of their freshman year”.

2. That is, “differences between students of economics and students from other disciplines were already apparent before students were exposed to training in economics”.

3. After one year of study these differences were maintained and stable.

4. By the final year of study, the emphasis on “achievement, power, hedonism” were sustained and economic students valuation of “benevolence”, which we might think of as being empathy towards others, had declined significantly.

In their 1993 article – Does Studying Economics Inhibit Cooperation? – economist Robert Frank and psychologists Thomas Gilovich and Dennis Regan summarised the extant literature and conducted a series of their own experiments to explore whether there are significant differences between “economists and noneconomists” in relation to whether they exhibit sociopathological tendencies.

They conclude that:

1. “that economists are more likely than others to free-ride”.

2. “economics training may inhibit cooperation …”

3. And, interestingly, that “the ultimate victims of noncooperative behavior may be the very people who practice it”.

4. And students in economics classes are more likely to lie when confronted with experiments about generosity – that is, claiming to be more generous than they were.

Further, an LSE Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper (No. 1938, July 2023) – Are the upwardly mobile more left-wing? – found that:

1. “that higher own status and higher-status parents independently produce Conservative voters.”

2. Higher own status leads to “opposition to redistribution”.

3. “individuals with the most Right-wing attitudes (and votes) are then those with high social status whose parents were also of high social status.”

The problem then is that not only are the number of economists emerging from universities declining but there is also a growing concentration among males from privileged backgrounds that are liable to exhibit the sorts of tendencies noted above.

Think about that in the context of designing progressive government policy.

It is not an attractive future.

I noted above that the decline was, in part, driven by the introduction of ‘business’ into the traditional economics faculties.

I didn’t want to give the impression, however, that this was the full story.

A not insignificant part of the decline can be traced to the way we taught economics in the 1970s and 1980s, which create sterile learning environments for students.

When I was an economics student, macroeconomics, for example, was taught from a critical perspective.

The textbooks we used contrasted the range of views of the various schools of thought and left it to the students to work out what they thought about the various conflicts that arose.

It was a more general education which emphasised reading and thinking about the classical literature in the subject.

We were ‘well read’ in the parlance and were required to study history, different economic systems (comparative systems), philosophy of science, logic, methodology, and more.

The subject matter was also integrated with knowledge from the other social sciences – which meant that we were exposed to literature in sociology and psychology for example.

That tempered the way we thought about policy and society.

In the 1980s that approach changed rather dramatically.

The new way of teaching out of the US created textbooks that provided students with ‘the one model’ and little critical analysis.

Universities started dropping the history of thought courses and the other approaches that had enriched the previous generation of students.

So there was little debate permitted – this is the model – learn it and that was it.

That model – the New Keynesian approach – defied reality and has spawned the terrible policies that I rail against regularly in my own work.

The depiction of the capacity of currency-issuing governments as just large households with similar financial constraints became central to the pedagogy and is, of course, plain wrong.

Remember the August 2008 article by Olivier Blanchard – The State of Macro – where he noted that mainstream economics at the graduate level has evolved to become an exercise in following:

… strict, haiku-like, rules … [the economics papers] … look very similar to each other in structure, and very different from the way they did thirty years ago …

Graduate students are trained to follow these ‘haiku-like’ rules, that govern an economics paper’s chance of publication success.

So if an article submission does not conform to this haiku-like structure it has a significantly diminished chance of publication.

So we get a formulaic approach to publications in macroeconomics that goes something like this:

- Assert without foundation – so-called micro-foundations – rationality, maximisation, RATEX.

- Cannot deal with real world people so deal with one infinitely-lived agent!

- Assert efficient, competitive markets as optimality benchmark.

- Write some trivial mathematical equations and solve.

- Policy shock ‘solution’ to ‘prove’, for example, that fiscal policy ineffective (Ricardian equivalence) and austerity is good. Perhaps allow some short-run stimulus effect.

- Get some data – realise poor fit – add some ad hoc lags (price stickiness etc) to improve ‘fit’ but end up with identical long-term results.

- Maintain pretense that micro-foundations are intact – after all it is the only claim to intellectual authority.

- Publish articles that reinforce starting assumptions.

- Knowledge quotient – ZERO – GIGO.

This routinisation creates publication bias and policy advice that has little bearing on reality.

And it is boring, which is why fewer students want to pursue these programs.

And the ones that do are prone to the tendencies I discussed above.

Teaching fictions is not going to be attractive to students who want to be exposed to critical perspectives that relate to the real world.

Economists are to blame for the decline in student numbers because they have engaged in such restrictive Groupthink.

Conclusion

Economics education as it is practised in our learning institutions is largely propaganda.

Students see through that and eschew it.

And the ones that don’t become the policy makers and the world deteriorates further.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

During the time Bill refers to, I went from an undergraduate student to an academic. After dropping out of higher education in the early-1980s because I couldn’t imagine spending the rest of my working life as an accountant (apologies to all accountants) and then doing a few interesting things for a number of years, I returned to university in the late-1980s to study Economics. I was wiser, including having my eyes widened to the many problems of the world, having had a comfortable but modest upbringing without too much to worry about.

Although the Dawkins’ reforms were disastrous for higher education in Australia, there was an underlying problem with the system as it was. I studied at Flinders University and there was a massive intake of students for the Bachelor of Economics in the year I returned. Very few of the students wanted to study Economics. They were looking for a business-like degree and, apart from accountancy, Economics was the only option. It was dry and boring and bore little resemblance to the world I had got to know and understand. I questioned a lot of the things I was taught but gave answers to exam questions to satisfy the markers (to get decent grades). Fortunately, I did a Geography major and studied Politics in first year (loved the section on Political Theory), which stood me in good stead and helped balance out the tedious and individualistic nature of Economics.

When the higher education institutions all became universities and business courses emerged and boomed, it filled a gap that had existed for a long time. That left large Economics Departments twiddling their thumbs, in large part because there were too many of them to begin with. A city the size of Adelaide (one million people at the time) had two large Economics Departments (Flinders and Uni of Adelaide) competing for a shrinking number of Economics students. There should only have been one department to begin with. There were too many universities then, and far too many now. Universities are very different places to vocational higher education institutions. Both have an important function, and they should be kept separate, as they were.

Universities are places of learning and knowledge building. They used to be good at the former and they are good at the latter in the physical sciences (where many things are cut and dry), but the social sciences have failed humanity for a very long time. The social sciences aren’t remotely reflective of the world we live in, have been ideologically driven, and try to remain ‘value free’ by shunning any discussion of, and recourse to, objective values, with Economics being the worst offender.

Each university should have specialty areas with ‘centres of knowledge building’ that are publicly funded, not only to ensure they are properly resourced, but to generate new knowledge without fear (perhaps MMT and Ecological Economics would now be mainstream). Many economists who were employed in the pre-Dawkins’ reform era to teach Economics to students who didn’t want to study Economics, and who later had to reinvent the subjects they taught and create designer degrees to attract students, should have been employed in these centres. Thus, many were wasted pre-Dawkins era and were later wasted creating useless new degrees. In more recent times, many have been sacked or driven away by head-kicking university bureaucrats who appoint head-kicking HODs (no longer democratically appointed by the department staff, as Bill points out). I fell into the latter group and, because I was a non-mainstream economist, have not been let back in. Such is the compartmentalisation of even heterodox economics, I’ve had the door closed on me by heterodox departments. The insidious thing about universities is that they now drive away the best people – the people who want to be academics in order to build knowledge and dispel the socially and ecologically destructive myths that threaten humankind’s existence on this planet.

The Dawkins Revolution https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dawkins_Revolution happened long after my time at university (engineering not economics) but even I could see, at the time of Hawke-Keating, that the rebranding of Institutes of Technology and CAEs and calling them universities would invariably lead to lower quality teaching and Mickey Mouse degrees – I can remember some of the humour surrounding that. The idea of having so many university graduates such that taxi drivers would need to be one to get a job was an appalling concept. Corporatisation of university administrations, the need to seek outside funding for survival lead to a student “importing” industry which we have today. The rise of the MBA and managerialism perfectly reflected the advancing neoliberal era. Throw in that punitive HECS idea and it’s a race to the bottom while the bureaucrats grant themselves massive pay rises.

Let’s offer a degree in surfboard shaping and so on. Even nursing became removed from the hands-on profession that it was when degree courses were introduced. All became a snowballing status game.

Our Professor’s story in this blogpost is from one who lived the university experience. Sadly, the decline in student interest in economics has not yet lead to a shake-up in the syallbi that remain in the dominant economics departments of universities. The GFC and Occupy Wall Street led to the rise of some student revolts in the formation of the Post Crash Economics Society and Rethinking Economics https://www.rethinkeconomics.org/about/our-story/. So far, without any significant effect on the needed paradigm change.

I submit that the neoliberal ideas propagated by neoclassical (or is that anti-classical) economics that are being perpetuated is no accident but an evolution by design to advance the gaslighting of society into accepting the only one (false) way of economics. All those right wing think tanks actively supporting a micro based on homo economicus and a macro formed as an aggregation of multiples of the micro form the basis of the orthodox academy and a supportive corporate media which own our politicians creating a huge obstacle to change. So hard to break the amplifying feedback loop of orthodox economics when economist don’t do history.

Much more noise is required to overturn the teaching and hiring of anti-classically trained economists where what they believe (based on the assumption of homo economicus operating within an environment which is assumed to return to equilibrium and without a time variable while being a standalone system where the effects on the ecology of our planet are considered to be an irrelevant “externality”. All based on barter without any understanding of fiat money) has no relation to the real world. Why would anyone want to study a theological pseudo-science that is unrelated to our existence? It must be about accumulation of financial wealth and bugger the rest.

I believe that teaching of economics needs to commence with the history of economic thought (as it once did) via an introductory component of the syllabus in secondary school. Commencing with the Physiocrats forward to today’s inane TINA view of anti-classical, the market will solve everything, financialised economics which is leading to end stage capitalism/return to feudalism/fascism.

Is democracy a cloak hiding the most hideous forms of dictatorships?

If it is a dictatorship in disguise, then democracy is an evil regime.

But, we don’t feel it that way.

The optminists say that democracy is the worst of the regimes, with the exception of all others.

The pessimists say that democracy degenerates into a plutocracy and this process unravels naturally.

But, is there some hope that we can curb the degeneration process?

Maybe there is, but curbing the degeneration process is not enough.

Maybe we need to do more than just have high moral standards.

The left/right divide is not a check against plutocrats anymore.

The “left” is a plutocratic asset, just like the “right” (what’s the diference between Boris Johnsson and Keir Stramer?…)

Maybe we need to take rights from the rich, in the inverse proportion of their property.

Just look at the US right now: they have oligarchs buying government departments. That’s not democracy.

But, how?

Well, nothing could change the status-quo, unless we take the Bastille again.

I noticed how much things changed between 1997-2004 when I was a student at the University of Newcastle.

I was the only person in my year that studied History of Economic Thought – nobody else was interested because it didn’t benefit them when it came to getting a graduate job with government or the private sector.

It’s not something I feel can be fixed or should be fixed – it’s just the way things are.

Most people studying economics are sycophants and only a very small percentage are not.

I have a lot of respect for anyone these days that can make it as an academic in economics and not sell out completely. There’s not too many of them. Fortunately, some good people in the comments section of this blog give me some hope.

I don’t fully agree with the explanation of ATAR’s.

it is a measure of compliance as much as it is of intelligence.

Females are generally more agreeable / compliant in my experience.

That must impact scores.

I think the researchers would fear being cancelled if they made such a statement.

However, in my limited experience as an econ tutor / lecturer my three smartest students were female. So much so that I could confidently use their exam papers or essays as a marking template.

The economic debate that has been silenced!

The aim of classical economics was to tax unearned income, not wages and profits. The tax burden was to fall on the landlord class first and foremost, then on monopolists and bankers. The result was to be a circular flow in which taxes would be paid mainly out of rent and other unearned income. The government would spend this revenue on infrastructure, schools and other productive investment to help make the economy more competitive. Socialism was seen as a program to create a more efficient capitalist economy along these lines.

These important concepts that have been abandoned on purpose and how is this deception accomplished?

These important concepts that have been abandoned on purpose and how is this deception accomplished?

The first and most brutal way was simply to stop teaching the history of economic thought. In schools say 60 years ago, every graduate economics student had to study the history of economic thought. You’d get Adam Smith, Ricardo and John Stuart Mill, Marx and Veblen. Their analysis had a common denominator: a focus on unearned income, which they called rent. Classical economics distinguished between productive and unproductive activity, and hence between wealth and overhead. The traditional landlord class inherited its wealth from ancestors who conquered the land by military force. These hereditary landlords extract rent, but don’t do anything to create a product. They don’t produce output. The same is true of other recipients of rent.

The classical economists had in common a description of rent and interest as something that a truly free market would get rid of. From Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill down to Marx and the socialists, a free market was one that was free of a parasitic overclass that got income without doing work. They got money by purely exploitative means, by charging rent that doesn’t really have to be paid; by charging interest; by charging monopoly rent for basic infrastructure services and public utilities that a well-organized government should provide freely to people instead of letting monopolists put up toll booths on roads and for technology and patent rights simply to extract wealth. The focus of economics until World War I was the contrast between production and extraction.

An economic fight ensued and the parasites won.

Professor Michael Hudson!

I remember my undergraduate economic days at Flinders University in South Australia. We were told in no uncertain terms that there was only a 30 % pass rate. We got a little bit of economic history (about 1 term) and some good methodology and statistics training. Given when I was there it was the beginning of the end I feel fortunate to have come out the other end with a generally well rounded degree, that and I can claim that I was taught by the legend Prof Bill Mitchell 😀😀

When I did History of Economic Thought at the University of Newcastle in 2001, I was the only student and had two lecturers.

So, there was more lecturers than students.

Prof Allen Oakley taught me the Quesnay, Smith, Ricardo, and Marx component.

Dr. Sudha Shenoy taught me Menger, Bohm-Bawerk, Mises, Hayek.

Two completely different perspectives as well.

Separation of economics from political philosophy led to economics’ decline into business training.

In order to make itself into a separate discipline from political philosophy, economics created a myth about the barter origin of money. If money had a basis outside politics, the thinking went, then economics could separate itself as a standalone science.

So economics invented the barter myth: Money was invented by the ancients to facilitate exchange.

Anthropology, however, pulled the rug out. There is simply no historical evidence supporting the barter myth of the origin of money (Innes, Humphrey, Graeber).

Money, far from being the product of the need for a medium of exchange, is instead revealed by anthropology to be a *political* creation (invented as a means for sovereigns to tax).

But since money arose out of politics, rather than organically as a means of exchange, economics is a branch of political philosophy, not a standalone science.

The question of politics is: “How is man to relate to his fellow man?”

Economics derives from the answer to that question.

Economiks education teaches climate change denial.