Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Low-paid workers in Australia – give with one hand, take back with the other

It is a public holiday in Australia today. Would you believe it is the annual Queen’s Birthday holiday – the Queen of England that is. How Australia maintains this colonial relic is down to progressive forces being divided on rather irrelevant details and some of them siding with the monarchists. Tomorrow’s blog post will analyse the recent ECB behaviour with regard to Italian government bond purchases. But today I consider the minimum wage decision that was handed down on June 1, 2018, by Australia’s wage setting tribunal, Fair Work Australia in its – Annual Wage Review 2017-18. This is the process through the Federal Minimum Wage in Australia is adjusted. The decision announced will increase the minimum wage by 3.5 per cent from July 1, 2018 so that the new minimum wage will be $719.20 per week or $18.93 per hour. Given that the annual inflation rate is running around 2 per cent (or thereabouts), the decision, on the face of it, would suggest that the real minimum wage is now higher than it was a year ago, which is a good sign. But over the last year, low-paid workers have had to endure cuts in pay rates for work during non-standard hours (so-called penalty rates), which Fair Work Australia made operational on July 1, 2017. For some workers the losses from the penalty rate cuts amount to more than $6,000 per year. So our wage setting tribunal is giving with one hand and taking it back (and then some) with the other. The most sordid aspect of all this is that many employers demanded Fair Work Australia deliver real wage cuts in the annual review.

In this blog post – Australia’s minimum wage rises – but not sufficient to end working poverty (June 6, 2017) – I outlined:

1. Progressive minimum wage setting principles.

2. The way staggered wage decisions (annually) lead to falling real wages in between the wage adjustment points.

I won’t repeat that analysis here. But it is essential background to understanding why the decisions taken by Fair Work Australia have been inadequate for a long time.

In its – 2018 Annual Wage Review decision – Fair Work Australia wrote:

… a national minimum wage of $719.20 per week or $18.93 per hour. (This constitutes an increase of $24.30 per week to the weekly rate or 64 cents per hour to the hourly rate) …

The prevailing economic circumstances provide an opportunity to improve the relative living standards of the low paid and to enable them to better meet their needs …

The level of increase we have decided upon will not lead to undue inflationary pressure and is highly unlikely to have any measurable negative impact on employment. However, such an increase will mean an improvement in the real wages for those employees who are reliant on the NMW and modern award minimum wages and, absent any negative tax transfer effects, an improvement in their living standards.

The Decision applies to around “2.3 millions workers or 22.7 per cent of all employees”.

1. “Compared to the position at the time of the 2016-17 Review, the economic indicators now point more unequivocally to a healthy national economy and labour market. The recent data has shown strong growth in full-time employment together with a high participation rate.”

2. “The labour market has improved significantly …”

3. “Business conditions remain positive. Profits grew by 4.3 per cent in 2017 and by 5.8 per cent in the non-mining sector. Survey measures of overall business conditions are at their highest levels since the global financial crisis.”

4. “Inflation and wages growth remain low.”

5. “Low wages growth has significant economic and social consequences.”

6. “modest and regular minimum wage increases do not result in disemployment effects or inhibit workforce participation.”

7. “Women are disproportionately represented among those on the NMW and those who are reliant on modern award minimum wages. It follows that an increase in the NMW and modern award minimum wages (particularly an increase above the level of bargained wage increases) will assist in reducing the gender pay gap.”

8. “The increases we propose to award will not lift all NMW and award-reliant employees out of poverty (measured by household disposable income below a 60 per cent median income poverty line)”

9. “But to grant an increase to the NMW and modern award minimum wages of the size necessary to immediately lift all full-time workers out of poverty, or an increase of the size proposed by ACCER and the ACTU, is likely to run a substantial risk of adverse employment effects.”

In summary, the rise in real minimum wages over the least several years has not exacerbated inflation nor damaged the employment prospects of the lowest paid.

This is despite what employers and conservative politicians keep claiming. But that shouldn’t surprise anyone.

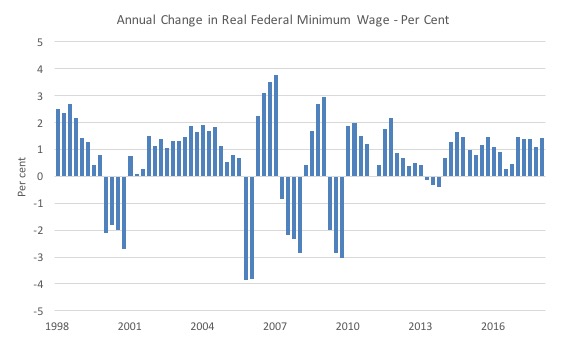

The following graph shows the annual percentage change in the real Federal Minimum Wage since the September-quarter 1998 up to September-quarter 2018 (the first quarter the new level will be applicable).

I have just assumed inflation is constant from its March-quarter value.

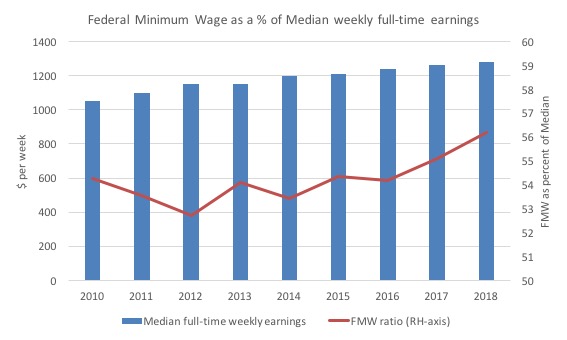

The Australian Council of Trade Unions had sought a rise of $50 per week, which they argued would further close the gap between minimum wage workers and the median wage and move the relatively back to 60 per cent of the median wage

The following graph shows Median weekly earnings of full time employees from 2010 to 2018 (blue bars) and the Federal weekly minimum wage as a proportion of the median (red line, right-axis, per cent).

For median earnings I extrapolated the annual growth from 2016-17.

Over time, this ratio has languished well below 60 per cent, which is the benchmark that is universally used to denote a ‘poverty threshold’.

The last two annual increases in the Federal Minimum Wage has moved the ratio upwards but there is still a significant gap remaining.

The Federal Minimum Wage is still around $48 per week shy of reaching the 60 per cent of median benchmark.

As usual, the peak employer body, Australian Industry Group (representing big business) said the decision was shocking and would be a “major disincentive to employment”.

They say that every time.

They had called for a real wage cut by telling Fair Work Australia that the maximum increase should have been $12.50 a week, around half the increase that was actually awarded.

The other industry body, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (representing small business) was also unhappy. As usual.

They claimed that there was no proof that higher wages “led to increased spending”.

They claimed that businesses would “cut hours, cut jobs or both” as a result.

They say that every time also. And they still continue to make profits as wages rise.

The Australian government did not show any leadership in the issue.

The Australian Government submission (March 13, 2018) to Fair Work Australia just reiterated all the usual claims that wage rises were damaging etc.

They opposed the ACTU submission writing that if that sort of wage rise was granted it was:

… likely to run a substantial risk of adverse employment effects of reducing the employment opportunities for low-skilled workers, including many young persons, who are looking for work.

The usual arguments which never show up strongly in the data.

While this annual decision appears to benefit low-paid workers it only presents part of the story.

The overhwelming problem is that the low-paid workers are about to be hit by the decision by Fair Work Australia last year to cut penalty rates (for weekend or public holiday work).

So workers are paid a standard hours rate, which cannot go below the minimum hourly rate specified by FWA.

However, if workers are engaged in non-standard hours they receive loadings, which the employers have long tried to eliminate.

For many low-paid workers, these penalty rates (loadings) provide a significant proportion of their weekly income.

FWA has bowed to the relentless pressure from employers and the conservative Federal government and has started cutting the loadings.

Workers in retail, Pharmacies, hospitality, fast food, are the first to experience the cuts as FWA alters the conditions sector-by-sector.

For some low-paid workers the cuts will see them lose around $6,000 per year.

So while some workers will get an increase of 3.5 per cent in the weekly pay as a result of the annual wage review they have lost much more via the penalty rate cuts.

The response of the employers is even more shameful when you consider that fact.

Wage Parity

I have already showed the parity with respect to the accepted poverty threshold (see above).

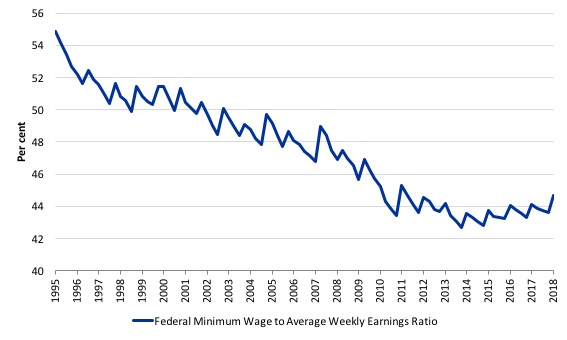

In terms of other parities with other wage earners, the following graph shows the ratio of the Federal minimum wage to the Full Time Adult Ordinary time earnings series provided by the ABS (the latest being for the December-quarter 2017). This series in now bi-annual (previously quarterly). I have interpolated on the basis of the most recent growth.

I simulated this series out to September-quarter 2018 (the quarter after which the latest FWC Annual Wage decision will start impacting) based on a constant growth in earnings (assessed over the last 12 months).

The new FWC applies from July 1, 2018 so will be constant over the rest of the 2017-18 financial year.

The logic of the neo-liberal period which encompasses the data sample shown was to at least achieve cuts at the bottom of the labour market, given that workers with more bargaining power would put up resistance against generalised cuts.

Successive minimum wage decisions have forced workers at the bottom of the wage distribution to fall further behind in relative terms.

In the December-quarter 1993, minimum wage workers earned around 55 per cent of the Full Time Adult Ordinary time earnings. By June 2018, this ratio will have fallen to around 43.8 per cent.

There has been a serious erosion of parity over the last 23 years.

But in the last two years, as the general Wage Price Index grows at record low levels and the FWC awards slight real wage increases to the minimum wage workers, the erosion in the parity has ended and the ratio is slowly rising (albeit in a staggered fashion).

Another way of looking at this dismal outcome is to compare the movement in the Federal Minimum Wage with growth in GDP per hour worked (which is taken from the National Accounts). GDP per hour worked is a measure of labour productivity and tells us about the contribution by workers to production.

Labour productivity growth provides the scope for non-inflationary real wages growth and historically workers have been able to enjoy rising material standards of living because the wage tribunals have awarded growth in nominal wages in proportion with labour productivity growth.

That relationship has been severely disrupted by the neo-liberal attacks on unions, wage fixing tribunals and other legislative initiatives that have eroded the capacity of workers to share in labour productivity growth.

The widening gap between wages growth and labour productivity growth has been a world trend (especially in Anglo countries) and I document the consequences of it in this blog post – The origins of the economic crisis.

But the attack on living standards has been accentuated at the bottom end of the labour market.

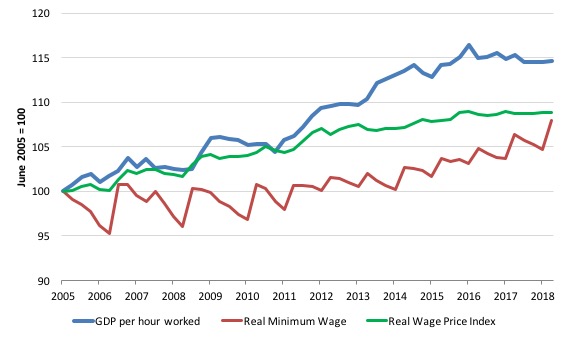

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (red line), GDP per hour worked (blue line), and the Real Wage Price Index (green line), the latter is a measure of general wage movements in the economy.

The graph is from the June-quarter 2005 up until September-quarter 2018 (indexed at 100 in June 2005 and extrapolated as above out to September 2018).

By June 2018, the respective index numbers were 114.5 (GDP per hour worked), 107.8 (Real WPI), and 104.7 (real FMW).

Overall, all workers have failed to enjoy a fair share of the national productivity growth, and that minimum wage workers in Australia have been largely excluded from sharing in any of the productivity growth although the low-paid workers have fared a little better in recent years.

Of-course, like all graphs the picture is sensitive to the sample used. If I had taken the starting point back to the 1980s you would see a very large gap between productivity growth and wages growth, which has been associated with the massive redistribution of real income to profits over the last three decades.

Staggered adjustments in the real world

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) since the June-quarter 2005 extrapolated out to September-quarter 2017 (the quarter in which today’s decision will start impacting) based on a constant (current) inflation rate.

This is the FMW expressed in purchasing power terms.

You can see the saw-tooth pattern that the theoretical discussion I provided in this blog post – Australia’s minimum wage rises – but not sufficient to end working poverty (June 6, 2017) – describes.

Each period that curve heads downwards the real value of the FMW is being eroded. Each of the peaks represents a formal wage decision by the Fair Work Commission. If the trough in the saw-tooth lies below the 100 line on the vertical axis then the real wage falls by the end of the period.

If the trough lies above the 100 point then the inflation during the year after the last wage decision has not fully eroded the real wage increase and so there is some modest net real wage increase for Federal minimum wage workers over the period.

The decisions since 2012 have provided for some modest real income retention by these workers although it depends on how inflation is measured.

You can also see the troughs are shallower in recent years than in the past because the inflation rate has moderated as a result of the GFC and the austerity since that has kept economic activity at moderate levels.

So while each adjustment provides some immediate real wage gain for workers, those gains are ephemeral and the inflation process systematically cuts the purchasing power of the FMW significantly by the time the next decision is due – these are permanent losses.

Conclusion

While Australia’s lowest-paid workers received a small wage rise last week the rise was not sufficient to end working poverty.

In terms of the accepted 60 per cent of median full-time weekly earnings, the Federal Minimum Wage remains some $48 per week shy of reaching that benchmark.

The gap reflects a history of decisions by Australia’s wage setting tribunals which have undermined the capacity of low-paid workers to enjoy real wage gains and keep pace with productivity growth.

The last two annual reviews have reversed those trends somewhat.

But we cannot consider this annual decision in isolation from last year’s penalty rate decision by Fair Work Australia, which delivered massive pay cuts to some of the lowest paid workers in Australia.

And if the employers and Federal government had their way, these workers would be enduring even harsher real wage cuts. So at least the FWC rejected their calls.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The lowest paid workers are also more likely to be casual, meaning their hours of work aren’t guaranteed. Minimum wages mean little if sufficient work isn’t provided.

The ACTUs ‘Change the Rules’ campaign advocates for a higher minimum wage, at a living wage, changing the rules unions can bargain under but there is no mention of ensuring full employment. They seem stuck in using neoliberal definitions of employment. Employment created by the private sector in the pursuit of profit.

I don’t see the campaign having an effect on real wages and bringing about great equity in national income. The shadow treasurer, a neoliberal, has stated that The ALP will ‘draw the line’ as to what rules change.

The debate is structured in neoliberal terms. Employment created only by the private sector, profit being a marker of efficiency, money being a scarce resource, increased government spending viewed as a ‘burden’ unless we tax the rich. It seems to challenge these assumptions, one is viewed as ‘radical’.

I hope you enjoy your holiday. If I’m doing the math right the Australian minimum wage is practically double (considering the exchange rate) what the US federal minimum wage is ($7.25/hour). My country treats its workers poorly. Australian workers are lucky to have someone like you argue for them.

Australia’s economy has miserably failed since 1991… The 2000 olympics overshadowed this failure and gave the country a false sense of recovery and growth but this was all very short lived and did not reflect reality. By the time it was 2007-2008 Australia’s economy was even further badly hurt but it was all covered up with some sort of ridiculous economic stimuli one after the other which made the country sink deeper and deeper into a non-recoverable situation. Since 2012 up until this day the Australian Government has been increasingly struggling to show consistent positive GDP q/q figures. With the domestic productivity continuously dropping since after the 2008 credit crisis, the Government had adopted one single main strategy to achieve positive GDP and that is consistently publishing an ever-growing non-stoppable growth in ‘population growth rate ‘. With Birth rate being stagnant and even dropping at sometimes, the growth rate has been obviously achieved by allowing a dramatic influx of immigrants, mostly non-skilled and refugees into the country. The huge masses of immigrants are the ones on the low wage income and are mostly on casual or part time jobs. Effectively, with all the above conditions and other related factors, Australia’s economy has been dented beyond repair.

Good luck to anyone wanting to find a quality job outside of a city. Cost of living rises in a city are higher than CPI of course. Then of course there’s housing crisis. All working towards making a hugely unequal society.

https://www.sgsep.com.au/publications/employment-insights-census

Our indifference to work being a legal right-{our indifference to: 15 USC § 3101] for every citizen of age-is the symptom of a decrepit species out of touch with its own well being—and out of touch with our modern market economy-with the loss of income to the economy as the result of unemployment, alone, anti-market, to wit:

THE LAW OF DIMINISHED INCOME TO THE MARKET FROM UNEMPLOYMENT [hereafter D/UE LAW]

Short Definition:

3% is the zero-sum threshold above which unemployment starts substantially undermining the Market–and the loss in income to the Market is compounded exponentially with each percentage point of increase in unemployment, above 3%.

Ref: “WHY DID WE LET FLINT ROT INTO DECAY: Ushering In A Trump Presidency?” Amazon/Kindle

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMC-4xDK8gk&w=560&h=315%5D – some Music for Bill

Bill – Republicans celebrating Queens Birthday is the same as non-Christians celebrating Christmas – a bit of fun and a day off!

Meanwhile in NZ there is much moaning from all business types about our new $16.50 NZD minimum wage ($15.25 AUSD). Oh to have a $20.45 NZD minimum wage already like you get in OZ ($18.93 AUSD)! NZ went all fundamentalist on slashing wages in the 90s and we’ve never, ever recovered.