Regular readers will know that I hate the term NAIRU - or Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment - which…

When intra-governmental relations became absurd – the US-Fed Accord – Part 3

I am writing this while waiting for a train at Victoria Station (London), which will take me to Brighton for tomorrow’s presentation at the British Labour Party Conference. The last several days I was in Kansas City for the inaugural International Modern Monetary Theory Conference, which attracted more than 200 participants and was going well when I left it on Saturday. A great step forward. I believe there will be video for all sessions available soon just in case you were unable to watch the live stream. Today’s blog completes my little history of the US Treasury Federal Reserve Accord, which really marked a turning point (for the worse) in the way macroeconomic policy was conducted in the US. In Part 1, I explained how from the inception (1913), the newly created Federal Reserve Bank, America’s central bank, was required by the US Treasury Department to purchase Treasury bonds in such volumes that would ensure the yields on long-term bonds were stable and low. There was growing unease with this arrangement among the conservative central bankers and, in 1935, the arrangement was altered somewhat to require the bank to only purchase debt in the secondary markets. But the change had little effective impact. The yields stayed low as was the intent. Further, all the prognistications that the conservatives raised about inflation and other maladies also did not emerge (which anyone who knew anything would have expected anyway). In Part 2, I traced the increased tensions between the central bank FOMC and the Treasury, which in part was exacerbated by the slight spike in inflation that accompanied the spending associated with the prosecution of the Korean War in the early 1950s. The tension manifested into open disagreement about the FOMC’s desire to raise interest rates and end the pegged yield arrangement with the Treasury. In Part 3, we discuss the culmination of that tension and disagreement and examine some of the less known and underlying forces that were fermenting the central bank desire for rebellion.

We left Part 2 with the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) riddled with internal dispute about what course of action it should take given the general feeling that it should break the arrangement with the US Treasury and start pushing up interest rates to head off the inflationary pressures associated with the Korean War expenditure.

The last meeting we discussed was held on February 6, 1951.

The – Minutes of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System – reveal that the Board was concerned about “several leaks to the press concerning the FOMC’s Jan. 31 meeting with President Truman.”

The discussions among FOMC board members were anything but cordial and the Chair of the Federal Reserve (Thomas McCabe) was accused by one board member (Mr Vardaman) of misleading President Truman by giving him the impression that the FOMC would “would support the Government financing program” when, in fact, the FOMC was really trying to abandon the peg and push up rates.

Vardaman sais that to present itself otherwise would be not only misleading the President but also the public. In turn, Vardaman was accused of leaking FOMC discussions to the media, presumably as a device to exert political pressure on the FOMC executive.

But the point was that it was clear that at this stage things were falling apart.

The next documented development came with a White House Meeting: February 26, 1951 between the President, some FOMC executive members, and some economists (Council of Economic Advisors, Office of Defense Mobilisation, SEC) and Treasury officials.

The meeting took place at 11.00.

The purpose of the meeting was to discuss interest rate policy and the continuation of the pegged arrangement.

We have three specific documents available:

1. Meeting Notes by William McChesney Martin, then assistant Treasury Secretary and future Fed Chairman.

2. Meeting Notes by Allan Sproul, then president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

3. Minutes of Federal Open Market Committee meeting held at 9.15 to discuss the White House Meeting.

Martin reaffirmed the Treasury view that it was of utmost “importance” to maintain “the public credit of the United States” because “unless it were maintained the Russians would have achieved their purpose completely”. The ‘reds under the beds’ narrative!

The meeting heard from CEA officials who “thought that the Treasury position in the matter of interest rates sound and appropriate”.

The CEA also considered that:

… the Federal Reserve certainly ought not to drive rates up by selling in the market and should work with the Treasury to keep confidence in a stable market …

That is, the pegged arrangement.

Martin reported that Sproul thought the Federal Reserve “should have stopped net-buying governments … long ago … under current conditions, was monetizing the debt in a way which strained the conscience of the Open Market Committee with respect to their responsibilities”.

McCabe was reported as reiterating the FOMC, which had a “statutory responsibility given to it by Congress”, wanted a clear direction from the Treasury, but the latter had delayed (partly due to sickness of the Secretary).

The Treasury position was made clear – abandoning the peg:

… would unsettle the market, bring an avalance of selling, and and seriously impair public confidence in the issues.

This is because the market would predict future yields would rise and bond prices fall – so they would bail out to avoid capital losses.

It is interesting to compare and contrast the way the Federal Reserve saw the meeting (Sproul’s notes) with those of Martin (from the Treasury).

While the Treasury thought that increasing rates and abandoning the peg would undermine confidence, the Sproul expressed the opposite view.

He also considered that fulfilling the FOMC’s “statutory responsibilities would not interfere with the rearmament program” because the private market would take up any debt the Treasury sought to issue.

Interestingly, Sproul considered the issue to go well beyond that of whether interest rates should be increased. He reiterated McCabe’s input that the FOMC “canot go on monetizing the Federal debt”.

It was clear that the FOMC pressure to abandon the pegged arrangement and push up rates was coming principally from the New York Federal Reserve Bank, of which, Sproul was the Governor. More about which later.

The FOMC appeared to be firmly of the view that the Treasury was engaged in a “delaying action” and that the FOMC:

… could not commit itself to the maintenance of fixed rates in the Government security market for any period regardless of what that might mean in terms of expansion of bank credit.

The delaying tactic referred to the President’s proposal to implement a “study” of the:

… ways and means to provide the necessary restraint on private credit expansion and at the same time to make it possible to maintain stability in the market for Government securities. While this study is underway, I hope that no attempt will be made to change the interest rate pattern, so that stability in the government security market will be maintained.

The historical importance is that the President was starting to realise that the tension between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury would not abate and that some circuit breaker had to be found.

The first meeting of the FOMC at 9.15 considered what the FOMC would say at the 11.00 meeting called by the President. The FOMC then reconvened at 14:15 to receive updates from McCabe and Sproul.

They considered the President’s memorandum that had opened the 11.00 meeting and expressed the Treasury view about the maintenance of the peg etc.

McCabe told the reconvened meeting that he “knew nothing of the memorandum before the White House meeting” but considered it was just a “further delay.

At any rate, he considered the FOMC should be part of the study to ensure they maintained leverage in the debate.

Events moved quickly after that.

On March 4, 1951, there was a – Joint announcement by the Treasury Secretary and the Chairman of the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee – which effectively declared a new ‘Treasury-Fed Accord’ had been reached.

The statement said:

The Treasury and the Federal Reserve System have reached full accord with respect to debt-management and monetary policies to be pursued in furthering their common purpose to assure the successful financing of the Government’s requirements and, at the same time, to minimize monetization of the public debt.

The Treasury released its own – Statement – on March 4, 1951 which said (among other things):

The Secretary of the Treasury announced today that there will be offered for a limited period a new investment series of long«term non- marketable Treasury bonds in exchange for outstanding 2-l/2%Treasury bonds of June 1$ and December l£, 1967-72, the details of which will be announced on March 19.

These new “non-marketable bond” would be issued to encourage “long-term investors to retain their holdings of Government securities, in order to minimize the monetization of the public debt through liquidation of present holdings of the Treasury bonds of 1967-72”.

What did that mean?

First, McCabe quit under pressure from the Treasury Secretary (see below) and Martin took over as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board.

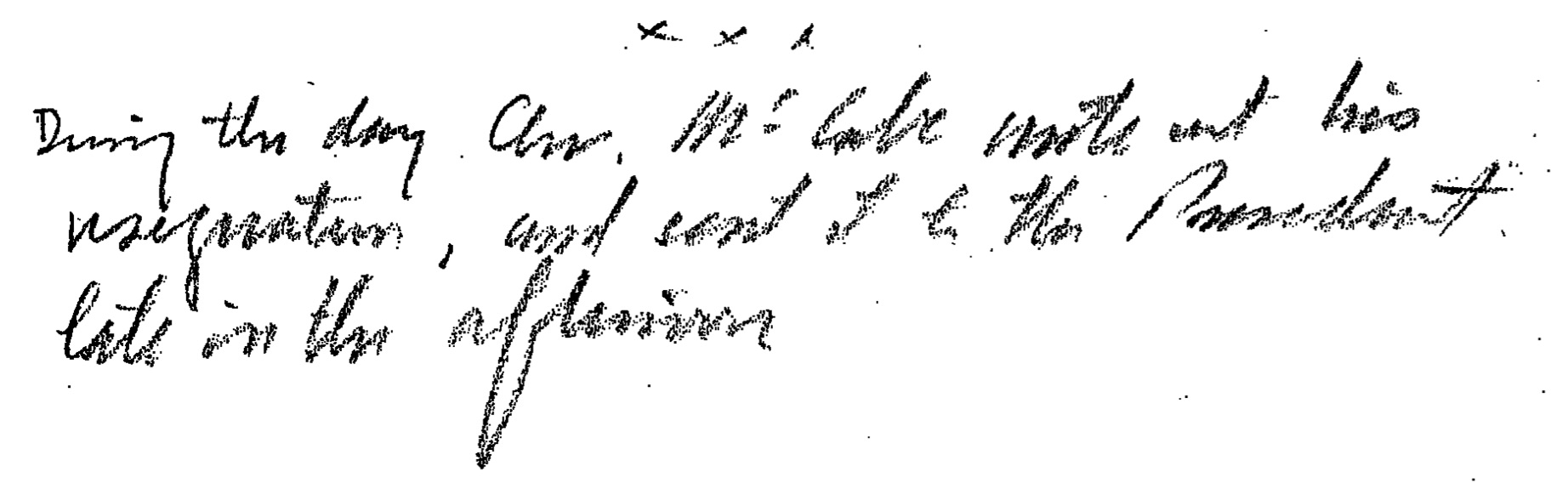

There is a little handwritten annotation to Sproul’s typed notes covering the White House Meeting: February 26, 1951, which I reproduce below:

Second, the Accord meant there would be a phased withdrawal by the central bank from the pegged arrangement. The bank would support the price of a 5-year notes issue and then let the bond market organise itself.

Third, according to Allan Sproul’s 1964 Reflection – The “Accord” – A Landmark in the First Fifty Years of the Federal Reserve System – published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in its Monthly Review, the conflict between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury arose because they had “overlapping responsibilities” between 1914 and 1951.

1. “two world wars had made the management and cost of the Federal debt a matter of major economic and administrative concern” …

but

2. “the development of credit policy as one of the primary means of Government influence on the total economy, and the open market techniques which the monetary authorities evolved to discharge their responsibilities under law, meant that an

overlapping area was created in which understanding and accommodation took the place of rigid legislative directives”.

Here he is discussing the balance between monetary policy (credit policy) and fiscal policy (spending)

Sproul claimed the conflict was over Treasury directives to the Federal Reserve to fund government spending at below market rates, especially as inflationary pressures were building.

One senses that Sproul couldn’t see the contradiction in his view that, on the one hand, the Treasury and Federal Reserve were a part of Government, and that the Bank was somehow a servant of the private market.

He also said that the Banking Act of 1935 “further mingled the areas of responsibility” because the FOMC was deemed to be:

… prepared to make open market purchases of United States Government securities, for the account of the Federal Reserve Banks, in such amounts and at such times as may be desirable.

He believed that the Act perverted the open market operations process such that they were no longer “undertaken primarily with a view to affecting the reserve position of member banks, but rather with a view of exercising an influence toward the maintenance of orderly conditions in the market for Government securities”.

He claimed this imparted an inflationary bias into the US economy although the empirical record did not reveal any particular bias had emerged.

The Secretary of the Treasury at the time, John Snyder reflected later (1969) – Oral History Interview with John W. Snyder – and considered that the “New York bankers” had pressured the Federal Reserve to agitate against the pegged arrangement.

He said that during WW2, Marriner Eccles (then Governor of the Federal Reserve) “had cooperated very splendidly with the Government to help hold the cost of the debt down”.

But as peace ensued and the Treasury sought to return to more normal deficits etc:

… the Federal Reserve was under pressure largely from the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

This pressure was continually blown up into a major policy conflict between the Treasury and the Bank, when, in fact, it was largely being driven by the New York Federal Reserve who “really the dictators of the monetary policy, credit policy, in the United States, and they began to press for higher interest rates”.

He recalled that he had an agreement with McCabe (then Bank Governor) to hold interest rates steady while the implications of the Korean war escalation were considered. But then, unannounced McCabe and Sproul rocked up to his office and told him they were raising interest rates.

Why did McCabe reneg?

According to Snyder “Mr. Allan Sproul, who was the president of the New York Bank, had put the pressure on Mr. McCabe.”

But why?

That is easy to understand and it is spelt “Wall Street”:

The New York bankers, and others, had put the pressre on him to show his independence from the administration …

He said the “whole thing” had been driven by the “Fed in New York”:

… to get back where the New York bankers could work with them and get the control of finance back in New York, don’t you see.

Remember Sproul was the FRBNY governor.

He said that:

Mr. Sproul — brought pressure on Mr. McCabe, who we learned later had great political ambition … Mr. McCabe had somewhat got the notion, whether these were promises, or dangling carrots, got the notion that he could be Secretary of the Treasury, and so he began to get very political in his attitude.

The “Treasury-Federal Reserve Accord” was released to calm the markets which had gone crazy.

The popular view of the Accord was that it “marked the birth of the modern Fed” (Source).

The claim is that the Accord, for the first time:

… created the idea of a modern central bank. Specifically … made macroeconomic stabilization the rationale for central bank independence.

Accordingly:

1. it “developed the practice of moving short-term interest rates in a way intended to mitigate cyclical fluctuations and maintain price stability”.

2. it “helped to create a viable free mar- ket in government securities whose stability did not require Fed intervention”.

3. it “reinvigorated the original structure of the Federal Reserve System” by reducing the power of the FOMC Executive in favour of more decentralised involvement of all FOMC members.

What this meant is that the Government bond market changed to allow the private bond traders to ‘make’ the market without the Federal Reserve intervention.

We read that:

As long as the Fed’s New York Trading Desk was pegging the price of government securities, there was no need for the market to develop the capacity to smooth price fluctuations. Dealers did not take speculative positions.

That last statement tells you what the incentives of Wall Street were to pressure the New York Federal Reserve to bale out of participation in the US bond market.

The Federal Reserve Bank’s own history unit wrote in 2013 – Treasury-Fed Accord – that the:

Independence and insulation from political pressures are essential to the ability of a nation’s central bank to conduct monetary policy.

The period before the 1951 Accord apparently compromised this independence, although I would say it allowed the government (Treasury and its bank) to function together in a consistent and integrated way in the pursuit of public purpose.

While the pegged arrangement largely locked out Wall Street, that can hardly be seen as a negative from a progressive lens.

The cry for independence is nothing more than a claim that monetary policy should work in the interests of the banks rather than the broader community goals.

Further, it marked the beginning of the modern obsession where governments rely on monetary policy to manipulate aggregate spending, a capacity that it does not have.

Despite the low interest rates and massive monetary injections in recent years, the impact on total spending of these policy shifts has been minimal.

Conclusion

The pre-Accord period, where the central bank would intervene in bond markets was very effective in stabilising the yields on government debt.

Onvr the Accord was signed, bond prices and yields became the plaything of the private bond market dealers, a situation that remains today.

Reclaiming the State Lecture Tour – September-October, 2017

For up to date details of my upcoming book promotion and lecture tour in Late September and early October through Europe go to – The Reclaim the State Project Home Page.

I am now in Brighton (UK) where I will be speaking at the:

The Brighthelm Centre, North Road, Brighton, BN1 1YD.

Time: The event will run from 14:00 to 17:00.

See RSVP Page

Then on Tuesday, we are formally launching our new book at the:

Newington Green Unity Church, 39a Newington Green, Stoke Newington, London, N16 9PR.

Time: The event will run from 18:30 to 20:30.

Entry: Free. All are welcome.

Please see – Ticket Page (entry free).

The Wednesday to Berlin!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The whole debate is an example of the tortured oppositional interplay of half truths in economic “thinking” and philosophy when what is required is an integration of those half truths that expresses a truly new policy thirdness/unity and the recognition of the new primary economic paradigm of Direct and Reciprocal Monetary Gifting. Of course a job guarantee could fit seamlessly within such philosophy and policies.

This has been a great series of posts on economic history. I wonder if the Bretton Woods arrangement, which had happened shortly before, also put pressure on the Fed to break with the Treasury, to the extent that it did.

If you add $1 trillion in additional federal spending, but increase taxes by $500 billion do you come out with $500 billion in net spending? All other things being equal. I struggle with this because I think MMT argues taxes don’t fund anything. I get that taxes extract wealth from some cohort or other, but if they don’t fund anything why would they affect net spending? Maybe I’m conflating a stock/flow kind of argument.

Chris Herbert,

“If you add $1 trillion in additional federal spending, but increase taxes by $500 billion do you come out with $500 billion in net spending?”

Yes, you come out with $500 billion in “net spending”. However, there are some points:

1) You can spend more than you tax. Actually, you probably always should spend more than you tax to avoid recessions. It is wrong to believe that you need to tax before you spend, and that the tax amount needs to be superior to spending amount.

2) Nominal result (total tax revenue – total spending in a given period, probably the inverse of what you called “net spending”) or primary result (total tax revenue – total spending, except interest expenses) is not a very meaningful concept. It is not useful to predict government default, economic growth, inflation, unemployment, or probably anything that matters. There are various different ways to achieve the same nominal result, through distinct kinds of public spending or public taxation, and each one of them will have a distinct effect on the economy. The number itself has little to no information at all.

“…bond prices and yields became the plaything of the private bond market dealers, a situation that remains today.”

Just a question or clarification from anyone

If I understand some of the reading of MMT, we do not need to issue government bonds, at least that is the gist of what I have been reading.

What I am confused about is that if a current account deficit requires a capital account surplus, then won’t a lack of government bonds make this impossible? Would not our property and stock markets experience much larger bubbles otherwise?

Cheers

Dingo, as far as I understand, MMT says that except for self-imposed constraints, a currency issuing government does not need to borrow the currency it issues in order to spend. There might be other reasons besides ‘funding spending’ where issuing debt that pays some interest rate might make sense though.

It seems to me that a country managing to run a current account deficit mostly means that people in other countries are willing to give up real goods in exchange for credits in the form of the deficit country’s currency. Ultimately, it is up to the people in the other countries to decide how much of that foreign currency they wish to hold that will determine how long that current account deficit will continue. When they don’t want to hold anymore, maybe they will just stop exchanging their real goods for the currency, or maybe they will try to exchange that currency for property or other assets, or goods, or services in the deficit country which could push up prices. I am not sure ‘bubble’ is the best way to describe that process though.

On a more personal level- I had never had a desire for Australian currency until the other day when Bill Mitchell announced he would send a signed copy of his book via your postal system (I assume) in exchange for some $AU. I guess I am now an international importer contributing to my own country’s trade deficit while lessening the Australian trade deficit. If you can get Mitchell to keep writing lots of books you might not need to worry about the current account so much.

“Ultimately, it is up to the people in the other countries to decide how much of that foreign currency they wish to hold that will determine how long that current account deficit will continue. When they don’t want to hold anymore, maybe they will just stop exchanging their real goods for the currency, or maybe they will try to exchange that currency for property or other assets, or goods, or services in the deficit country which could push up prices. I am not sure ‘bubble’ is the best way to describe that process though.”

Hi Jerry,

I think this piece best explains what I am trying to ask.

“As of the end of 2012, US corporations had an estimated $1.8 bln of cash (liquid financial assets) on their balance sheets. European companies had an estimated $1.3 trillion, while Japan’s corporates had cash holdings of $2.4 trillion. And now, imagine that those funds need to be placed somewhere, and that $5.5 trillion is also likely to be levered up several times during the circuit of capital.

In addition, another even larger pool of capital emerged that also largely stayed out of the circuit of production via direct investment, but stayed within the circuit of capital; namely the reserve managers: the central banks and an increasing number of sovereign wealth funds. Those funds essentially arose in the circuit of capital itself. Financial products have to be created, sold and distributed; creating new speculative opportunities.”

[Bill deleted a link he did not wish to publish]

My original question was asking how is it possible to have a current account deficit if we do not offer bonds as one of the means by which to invest those ‘credits’? People can’t just leave it as cash, they have to invest their surplus savings in something, whether its a bank or super or fund, which in turn then invests in something else, usually into companies, fixed interest and real estate. Stock markets and real estate can only take so much, the rest goes into bonds. If you take a look at a long term chart of the US 10yr (just google US 10 year since 1900 chart) you will see the sheer magnitude of this problem (interestingly, yields peaked when deregulation started to be phased in).

Dingo, of all the many problems the world has to deal with, worrying about what people who have more money than they want to spend are going to do with it is not a top priority for me :). Of course they can leave it as cash. Or they could stick it in a bank and get a very low interest rate return. Or they could lend it out themselves (which buying a corporate bond is similar to), or invest it in something productive, or buy some real asset. They could even give it to me, but that doesn’t seem to happen much. They wanted the money in the first place right? Otherwise they wouldn’t have it most likely… They can figure out why they wanted it and what they want to do with it.

Fascinating blog post