It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

Household debt in Britain on the rise – lessons not learned

Economic debate in Britain in the last year or so has been dominated by the Brexit issue. Both sides of the debate have swamped the public with claims and counterclaims that mostly just seek to confuse. My position was clear – if I was a British voter I would have been voted to Leave. Some 9 months or more later my opinion has not changed. The EU is a right-wing corporatist failure which deliberately impoverishes its citizens and should be dismantled as soon as possible. The Brexit debate, whatever your view, has, however, clouded other trends in Britain that are clearly, and immediately, more damaging that anything that might happen when Britain finally regains its independence from the thugs in Brussels. The latest data relating to household debt in Britain confirms what we have known all along and first raised in 2011. British growth is reliant on the private domestic growth in credit and indebtedness, which was the growth drivers that were present before the GFC. Which means one thing: the current growth will not be sustainable unless there are significant changes in the composition of final expenditure in the UK. With private income growth lagging well behind consumption growth and the external sector draining growth, the solution is for the government to abandon its austerity obsession and increase the fiscal deficit. That would support private income growth and provide space for some private balance sheet restructuring which is so sorely needed. Lessons do not seem to have been learned.

Let us, briefly, travel back in time – to 2011 to be exact. George Osborne had delivered his second fiscal statement to the British Parliament on March 23, 2011 after taking office in 2010.

In the June 2010 fiscal statement, his first, Osborne announced rather harsh spending cuts as part of his ideological obsession with cutting the fiscal deficit, despite the economy still being in a parlous state.

Growth had just resumed after 6 consecutive quarters of sharp contraction and the newly-elected British government det about undermining that growth as quickly as it could.

The changes made in 2010 had made matters worse. Fiscal austerity has failed to rebalance the British economy away from a reliance on the growth in household debt to sustain consumption expenditure and growth. Further, by early 2011, it was clear that the British economy was starting to exhibit dynamics consistent with the unsustainable pre-crisis period.

On April 29, 2011, I wrote the blog – I don’t wanna know one thing about evil – where 1 considered the – 2011 British Fiscal Statement – specifically in terms of how the Government thought that growth would unfold over the next years.

Under the heading “A strong and stable economy” (Page 7) we read:

… Over the pre-crisis decade, developments in the UK economy were driven by unsustainable levels of private sector debt and rising public sector debt. Indeed, it has been estimated that the UK became the most indebted country in the world … Households took on rising levels of mortgage debt to buy increasingly expensive housing, while by 2008 the debt of nonfinancial companies reached 110 per cent of GDP. Within the financial sector, the accumulation of debt was even greater. By 2007, the UK financial system had become the most highly leveraged of any major economy … This model of growth proved to be unsustainable …

This discussion was in the context of a vulnerable and unbalanced economy relying too much on private sector indebtedness for growth and being very sensitive to housing price movements.

That was the only reference to household debt in the 2011 document, which at the time was odd given the role played by the unsustainable credit growth in the UK in the engendering the crisis in the first place.

I noted at the time that a growth strategy that relies on the private sector increasingly funding its consumption spending via credit (or running down its saving balances), especially if accompanied by flat wages growth, is unsustainable.

Eventually the precariousness of the private balance sheets (or the finite capacity of accumulated saving) becomes the problem and households (and firms) then seek to reduce debt levels and that impacts negatively on aggregate demand (spending) which, in turn, stifles economic growth.

When those adjustments are stark – as they were in the global financial crisis – especially when housing prices collapsed – the consequences are wide-ranging and very damaging.

A recession induced by a private debt crisis is usually deeper and harder to resolve than a downturn arising in the real sector from, for example, a loss of consumer confidence.

When there are unsustainable stocks of private debt to deal with the adjustment becomes more complex. That is one of the lessons that the global financial crisis should have taught all the mainstream economists – although the evidence is that there has not been much learning going on.

After that reference to household debt, the rest of the 2011 Fiscal Statement provided an obsessive coverage of the evils of public debt and the need to reduce it. The justification for the harsh austerity program was all tied up in spurious public debt arguments.

Soon after the only reference to private sector debt in the 2011 Document, it was stated that the “The Government’s economic policy objective is to achieve strong, sustainable and balanced growth that is more evenly shared across the country and between industries”.

What is required for a growth strategy that aims to reduce private sector debt (given the 2011 Fiscal Statement recognised it as a major problem) and public sector debt (to satisfy the ideologues) while maintaining the sort of growth estimates that have appeared in successive fiscal statements in the UK?

Clearly, the external sector has to come up trumps and provide the demand stimulus to the economy capable of (more than) offsetting the net saving desires of the private domestic sector and the fiscal drag coming from the public austerity program. If that doesn’t occur then the economy will shrink.

Alternatively, the economy might grow a bit if the austerity proves to be ineffective and/or the private sector fails to run down its debt.

In the 2011 Fiscal paper (Page 89, Annexe C) the British Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) presented the forward estimates or “the OBR’s key projections for the economy and public finances”. The Annex said that “(f)urther detail and explanation can be found in their report”. At the time, I thought this was a joke given how long it took me to actually find the detail. It was well hidden and for good reason.

From Table C.1 we saw very optimistic forecasts for Household consumption and net exports over the period 2011 to 2015. However, even if the net exports had come in at forecast (and they didn’t – not even close), the real GDP growth forecast would also have requred the very strong recovery in household consumption that was forecast.

At the time, I thought the projections were interesting given that growth in Real household disposable income was forecast to be negative that year and then sluggish in the following years of the forecast horizon.

Further, growth in real household disposable income at the time was sluggish and continued to be so while growth in real household consumption was much higher. How come?

The difference was more debt and/or run down of savings.

The fact of the matter was that at a time that George Osborne was hacking into public spending and derailing growth through fiscal drag, he was in full knowledge that increased private domestic debt levels would drive any growth.

The OBR published this document (April 21, 2011) – Household debt in the Economic and fiscal outlook – which said:

Our March forecast shows household debt rising from £1.6 trillion in 2011 to £2.1 trillion in 2015, or from 160 per cent of disposable income to 175 per cent. Essentially, this reflects our expectation that household consumption and investment will rise more quickly than household disposable income over this period. We forecast that income growth will be constrained by a relatively weak wage response to higher-than-expected inflation. But we expect households to seek to protect their standard of living, relative to their earlier expectations, so that growth in household spending is not as weak as growth in household income. This requires households to borrow throughout the forecast period.

The OBR said at the time that “net worth is forecast to decline as a percentage of income as the household debt ratio is expected to rise and the household assets ratio is expected to fall”.

It was small-print analysis that the major UK newspapers missed altogether. But it told us that while the British government was making a fuss about the debt levels – both public and private – its own growth strategy was contingent on the private domestic sector taking on a rising debt burden over the forecast period and becoming relatively poorer?

What the British Conservative government’s strategy amounted to was reducing public debt at the expense of more private debt – at a time that private domestic debt was at unsustainably high levels.

I noted at the time that prudent fiscal management requires exactly the opposite strategy when the economy is floundering.

That was 6 years ago.

There was a UK Guardian editorial yesterday (April 5, 2017) – The Guardian view on rising personal debt: more prudence please – that reflected the growing concern – yes, it is recent – about the growth in private debt in the UK.

The Guardian editor said:

The twin pressures of rising inflation and slowing pay rises are squeezing household incomes. The ratio of personal debt to household income, which fell steadily in the years after the financial crisis, has now again begun to rise. Last week, new figures were published showing February brought the highest increase in credit card debt in 11 years …

The British economy’s failure to wean itself off an addiction to growth fuelled by an expanding consumer debt bubble is bad for consumers, and bad for the economy as a whole.

And, the consequences that will follow have nothing to do with Brexit but all to do with the flawed macroeconomic policies pursued as mainstream by the British government.

Yes, as the Guardian notes “It makes recession more likely, and, when it comes, deeper and longer. The human costs of getting into problematic debt are no less profound: people are a third more likely to develop mental health issues if they find themselves struggling with debt.”

So why this sudden concern? The problem has been staring Britain in the face for year – it helped cause the GFC – it prolonged its negative effects – and it is setting Britain up for another round of crisis.

The answer to my question lies in the complacency and diversions that the mainstream economic narrative sets up. False problems are constructed and nurtured – public deficits and debt, Brexit, the loss of the British financial sector to the outer hebrides or somewhere, an invasion of Spain over Gibralter – and the real problems ignored – and made worse by the pursuit of solutions to the false problems.

The UK Guardian editorial is similarly sidetracked. It focuses extensively on “a new regulatory regime” to reduce household borrowing – make it more expensive, more difficult to access, etc.

I am not saying that a more stringent regulatory environment duly enforced is not required. Significant banking reform has to take place before financial stability is guaranteed and the banking system works to advance general well-being rather than feed the coffers of their shareholders while undermining the well-being of the rest.

But, rightly, the UK Guardian article does acknowledge that there is a deeper malaise:

None of this, however, will reduce the root causes of problem debt. The most common reason people get into unmanageable debt is a drop in their income. A growing number of low-income families face a grim mix of stagnant wages, increasing inflation and huge cuts to tax credits and benefits in the coming years, which will force growing numbers of people towards unsustainable debt.

But then loses the plot in offering this solution:

The most significant thing the government could do would be to reverse the unnecessary and expensive tax cuts it has planned for businesses and more affluent families, and use the proceeds to cushion the blow of its unfair and unwarranted cuts to benefits and tax credits.

When in fact, the most significant thing the government could do at a time that the external sector is draining growth through the Current Account deficit and there is a need for households to save more is to expand its own deficit to provide support for income growth generally, which, in turn, simultanously supports private balance sheet rebalancing and consumption.

That is how to break the nexus between low private income growth and rising household debt.

Even the Bank of England has finally stopped doing the ‘Brexit will be ruin’ thing and turning its attention to the real issue of household debt.

In his Evidence before the Treasury Select Committee on January 11, 2017, the Bank’s governor was asked whether he would “conclude that Brexit is no longer the most significant near-term domestic risk to financial stability?”.

He replied:

That is the conclusion that we came to by the time of the November report.

The Brexit vote was in late June. By November (at least), the Bank of England had shifted positions.

The governor elaborated:

We said that the biggest risks to financial stability in the UK are global and non-Brexit related. We will set those aside. We identified the four major domestic risks to financial stability-current accounts being a crossover risk between international and domestic-in detail in the report.

And what are those domestic risks?

The governor and his officials at the Committee hearing said:

We have been very alert … over a number of years to the growth of household debt, partly because a highly indebted household sector is one that is more vulnerable to shocks, should they come along … countries with very high levels of consumer credit and household debt tend to have deeper recessions for a given shock …

the level of household debt can, in fact, be a source of economic shock in and of itself. Were we to arrive, as we did before the crisis, at a position where there was a so-called debt overhang, where households had effectively taken on more debt than they later decided they could repay, it triggers a deleveraging and a sharp rise in household saving, and falling consumer spending …

Obviously, we do not want to end up where the economy was in 2008-09, because one of the reasons why the recession was so deep and prolonged was the overhang of that debt and the behaviour of households. It is a relevant point that there has been quite a substantial improvement, in part because people have not been borrowing and have been paying it down. They have now started to borrow.

A week or so ago (March 27, 2017), the UK Guardian took up this theme again – UK’s borrowing binge is worrying the Bank of England – announcing that “alarm bells are jangling at the Bank of England. Households have been on a borrowing binge. Consumer spending is being underpinned by debt, with an increased dependency on personal loans, payday loans, car finance and – in particular – credit cards.”

The Bank of England’s February Inflation Report (released February 2, 2017), noted that:

… consumption growth is projected to slow in coming quarters, as real income growth slows.

And that “consumer credit has risen in recent years … the most recent pickup in consumer credit growth has re ected growth in credit card and other borrowing, such as personal loans … While some of the increase in borrowing may be matched by increased saving, the easing in credit conditions is likely to have supported consumption growth in recent years. And credit conditions are likely to continue to support consumption in coming quarters.”

Unsustainable is the word to come to mind.

Household debt in Britain is now returning to the record levels set just before the crisis.

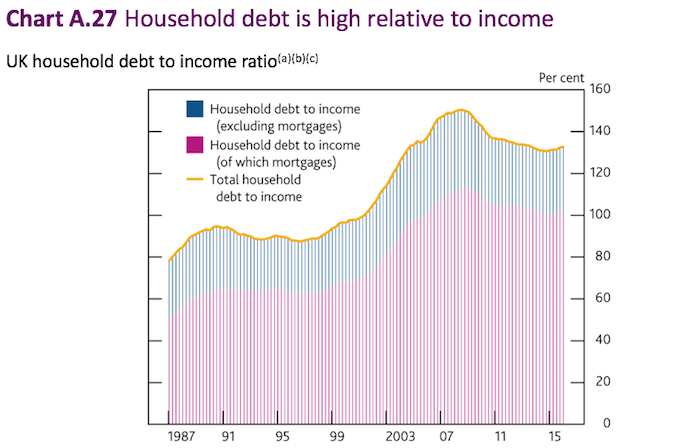

This graph comes from a Bank of England presentation – UK Household Indebtedness – and shows the trends in household debt.

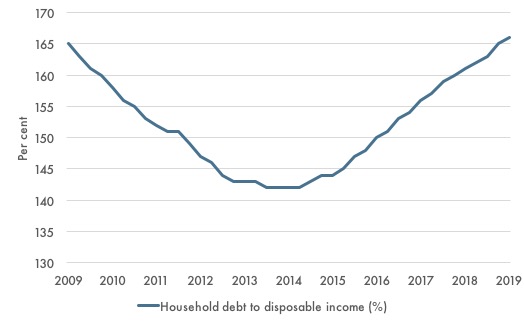

The following graph shows the Office of Budget Responsibility’s forecasts of the Household debt to disposable income ratio out to 2019 (data.

It is not a pretty sight with incomes growth lagging.

Finally, the Bank of England produced this graph, which shows the vulnerability of households carrying debt to a rise in unemployment. The percentage has been rising again. Dynamics being repeated.

Conclusion

For all the talk about re-balancing the British economy and justifying austerity under this catchcry, the data trends confirms what we have known all along and first raised in 2011.

That is, a return to the sort of growth drivers that were present before the crisis. Which means one thing: the current growth will not be sustainable unless there are significant changes in the composition of final expenditure in the UK.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

An excellent analysis, thanks.

A parallel currency that is earned into existence for contribution to the common good is on its way though Bill. One that the markets will be able to invest in because of sustainability that’s baked into its design.

Debt forgiveness has to happen but only if there’s something in it for the creditors and that for me, is proof that the creditors are willing to support a more sustainable economy.

And the way to do that is way to give them proof that they care.

Bill,

The BoE has abetted the consumer credit boom including mortgages using various funding schemes e.g. help to buy and claimed special funds for small businesses which have leaked into the consumer area ( SME’s have been paying back loans rather than paying usury rates offered by the banks).

Incredible complacency from the Bank of England only a few month’s ago:

‘”Interest rates are still very low, and are expected to remain so for the foreseeable future, so there are fewer concerns on debt servicing than there were in the past,” said Andy Haldane, the Bank’s chief economist, last week.

“There are reasons not to be too alarmed about it ticking up, but it is absolutely something we will watch carefully,” he said.’

Even more complacency in Denmark where the private debt/GDP ration is 265% when I last looked:

‘”By far the major part of Danish households’ debt is carried by families who are robust enough to be able to handle shocks to interest rates or incomes,” Rohde said yesterday in a written reply to questions. “The threat to financial stability from that corner is therefore not serious in the current situation.”

Sleepwalkers?

Professor Bill Mitchell,

Here’s a write up about the Indian govt’s fiscal def. obsession using MMT for analysis by an Indian writer for an Indian audience. We here have also been cursed by the ‘3% target’. Its really well written. Hope you like it and find time to comment on it.

https://thewire.in/121017/modern-money-obsession-fiscal-consolidation/

The ideology behind QE and internal devaluation that is dominant in Europe these days is predicated on the assumption that growth can only come from positive and growing exports (a zero sum game in a mercantilist Wordl) or a return to household debt; never from fiscal deficit. In Spain the government is trying to engineer a new real estate bubble even though they should by now know that it was their fiscal “irresponsibility” that led to growth between 2014 and 2016. Lessons not learned, as Bill says.

Ganpati

Thanks for that. A very well-written article which draws on the experience of the (not named in the article) Bradbury Pound that was used to allow the British government to transfer resources from the private sector to the state in order to support the 14 – 18 war effort. It is a very good example of MMT working in practice.

Mark Bahnisch continues to be proven correct – no matter how badly broken the system, nothing will change while there exists no broadly accepted alternative socio-economic narrative.

@Leftwinghillbillyprospector Spot on!

@Mark Riddell,

yes, it depresses me sometimes. Nearly a decade after a cataclysmic failure, neo-liberalism remains as dominant as ever. True, things are changing but the pace is agonizingly slow and often in the wrong direction (ie, the election of Trump etc). Most people simply can’t imagine anything greatly different to what we have now. One of our former prime ministers – who was himself a architect of a fair few of the neo-liberal reforms! – recently echoed the comments of the new council of unions president that “neo-liberalism has run it’s course”.

I agree that it has done so but the problem is that it just refuses to go away. Like the walking dead it staggers on and on. Here in Australia – which never experienced a recession following the 2008 collapse, thanks largely to a swiftly-implanted fiscal stimulus – we appear to be getting close to the limits of replacing government deficit spending with private sector credit creation, as it seems that repaying borrowed money cannot be made much cheaper, if at all, the private sector is choked to the eyeballs on debt without precedent and government still insists on aiming for surpluses. Employment and general economic growth are suffering for a lack of spending and a crash seems on the cards sooner or later.

But in places where such a crash already occurred – Britain is one as this article says – far from growth having to now be led by income growth rather than private credit growth, the cycle of private credit growth has simply resumed anew.

Neo-liberalism is a vicious cycle, destroying itself but then rising from the ashes to begin the cycle of growth ending in implosion again – and probably again and again and again, until there is a seismic shift in the publics understanding. This might take years, it might take decades, it might take a lifetime or longer.

@Leftwinghillbillyprospector I’m not as gloomy as you.

The dollar is widely regarded as being overvalued and since the global monetary system uses it as it’s reserve currency, the chances are that when a more sustainable alternative pops up, it’s likely that investors will flock to it as a safe-haven asset class.

As for the man-in-the-street, well again, I’m not quite so gloomy. People are ready for change, especially if there’s something in it for them.

That something will help them pay for things and account for the good they’ve done in their community and it will link that contribution to their entitlement so that we all become more sharing, more caring and more resourceful.

It won’t be long before that happens. 10 years i’d say, max.

Election of Trump was an MMT event. He does not certainly believe that state can run out money. I hope he nominates like-minded people to the World Bank and IMF

@Mike Ridell: “It won’t be long before that happens. 10 years i’d say, max.”

That’s what I thought 10 years ago. Here’s hoping you’re right though!

thank you so much Bill, this article will be another for discussion at Sunday dinner with my tory loving parents : )