Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Australia – wages growth at record low as redistribution to profits continues

The Australian Bureau of Statistics published the latest – Wage Price Index, Australia – for the September-quarter yesterday and annual private sector wages growth fell to 2.1 per cent (0.5 per cent for the quarter). This is the third consecutive month that the annual growth in wages has recorded its lowest level since the data series began in the December-quarter 1997. In the 2015-16 fiscal statement, the Government assumed wages growth for 2014-15 would be 2.5 per cent rising to 2.75 by 2017. On current trends, that is highly unlikely to occur, which means the forward estimates for taxation revenue are already falling short and the fiscal deficit will be larger than assumed. Depending on how we measure inflation, the annual wages growth translates into a small real wage rise or fall. Either way, real wages are growing well below trend productivity growth and Real Unit Labour Costs (RULC) continue to fall. This means that the gap between real wages growth and productivity growth continues to widen as the wage share in national income falls (and the profit share rises). The flat wages trend is intensifying the pre-crisis dynamics, which saw private sector credit rather than real wages drive growth in consumption spending. The lessons have not been learned.

Even the conservative government is now worrying about the fiscal implications of the low wages growth.

In a speech delivered yesterday by the Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison to the Bloomberg Summit in Sydney – A National Platform for Economic Growth and Jobs – he said that:

Australians need to earn more, they need to earn more with real wage growth. We also need to earn more from the way we are competing on the world stage …

It is through increased competition and gains in productivity that we will secure stronger growth in the real wages of Australians.

You can get a pay rise two ways in this country; the boss can give you more because you have increased your productivity or the Treasurer can by cutting your personal income taxes – I would like to see both.

Unfortunately, real wages growth in Australia these days does not follow productivity growth in any proportional way as it did in the period before this neo-liberal domination began.

The conservatives like to say that productivity growth is passed on to workers but they know that for the last three decades or so that has not been the case. Moreover, the labour market policies of successive governments on both sides of politics have created a situation where it is increasingly difficult for workers to gain real wages growth.

The Fairfax commentary (November 18, 2015) – Wage growth hits record low as Scott Morrison tries to lift incomes – noted that annual wages growth in the September-quarter 2015 of “2.1 per cent for the private sector” is “the lowest in records spanning back 18 years”.

The wage series used in this blog is the quarterly ABS Wage Price Index published by the ABS. The Non-farm labour productivity per hour series is derived from the quarterly National Accounts.

A compact dataset can be downloaded from the RBA Table H2 Labour Costs and Productivity. I extrapolated the average growth over the last five years to get the March-quarter productivity result, given the national accounts data is not released until early June.

Please read my blog – Inflation benign in Australia with plenty of scope for fiscal expansion – for more discussion on the various measures of inflation that the RBA uses – CPI, weighted median and the trimmed mean The latter two aim to strip volatility out of the raw CPI series and give a better measure of underlying inflation.

The deflator used in this blog is the RBA’s ‘core’ or ‘underlying’ inflation measure. The RBA says (Source):

Because of the noise in short-horizon movements in the CPI, policymakers and other analysts often look to measures of underlying or core inflation, which should be subject to less noise than headline inflation …

The most widely used underlying measure is the inflation rate for the CPI basket excluding a few items which historically have had particularly volatile prices. The items typically excluded are various types of food and/or energy, and in some countries the resulting measure is often referred to as ‘core’ inflation. These ‘exclusion’ measures of underlying inflation remove the direct effect of movements in the prices of those items on the rationale that they tend to be volatile and often not reflective of the underlying or persistent inflation pressures in the economy. They are obviously easily calculated and explained to the public.

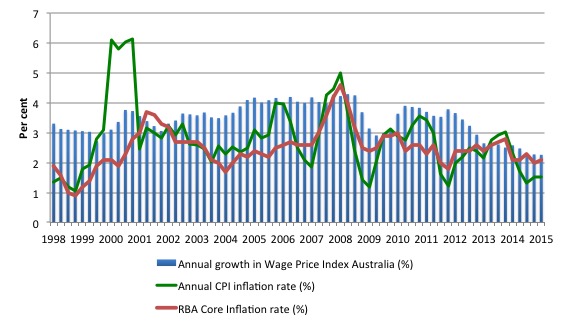

Nominal wage and price inflation

The first graph shows the overall annual growth in the Wage Price Index since the September-quarter 1998 (this series was first published in the September-quarter 1997).

I also superimposed the annual inflation rate (Consumer price index) – the green line and the annual core inflation rate (red line). The bars above the green or red lines indicate real wages growth and below the opposite.

The big funny-looking jump in 2001 in the CPI-inflation rate series reflected the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax which created a once-off adjustment in the level of the CPI.

Once we take out the volatile factors in the CPI, we see that the real wage has fallen in five out of the last seven quarters. In the last three quarters it has fallen marginally (at decimal places) in March-quarter 2015 then grew by 0.2 per cent (that is, hardly at all) before declining marginally in the September-quarter 2015. Rounding to one decimal place gives a zero growth for the September-quarter 2015.

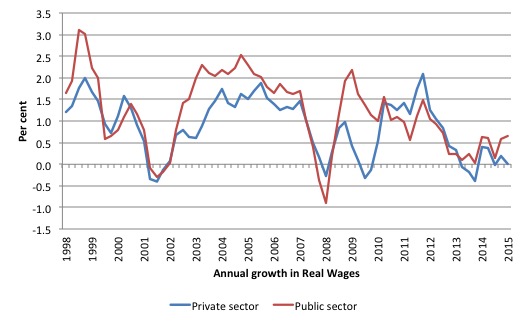

Real wages growth subdued in September-quarter

The following graph shows the annual growth in real wages from the September-quarter 1998 to the September_quarter 2015 for the public and private sectors.

After a few quarters of hard real wage cutting in 2013-14, the private sector returned to positive real wages growth but at very subdued rates.

In the last three quarters real wages growth has been close or at zero.

The rise in real wages in 2012 into 2013 was the result of the strong economic growth supported by the fiscal stimulus. The declining profile after that is associated with the end of the mining investment boom exacerbated by the obsessive fiscal austerity that was introduced (too early).

Workers not sharing in productivity growth

One of the salient features of the neo-liberal era has been the on-going redistribution of national income to profits away from wages. This feature is present in many nations.

This has occurred because real wages growth has lagged behind productivity growth and the extra real income produced as been expropriated by capital in the form of profits.

The suppression of real wages growth has been a deliberate strategy of business firms, exploiting the entrenched unemployment and rising underemployment over the last two or three decades.

The aspirations of capital have been aided and abetted by a sequence of ‘pro-business’ governments who have introduced harsh industrial relations legislation to reduce the trade unions’ ability to achieve wage gains for their members. The casualisation of the labour market has also contributed to the suppression.

That redistribution of national income to profits continues in Australia.

I consider the implications of that dynamic in this blog – The origins of the economic crisis. As you will see, I argue that without fundamental change in the way governments approach wage determination, the world economies will remain prone to crises.

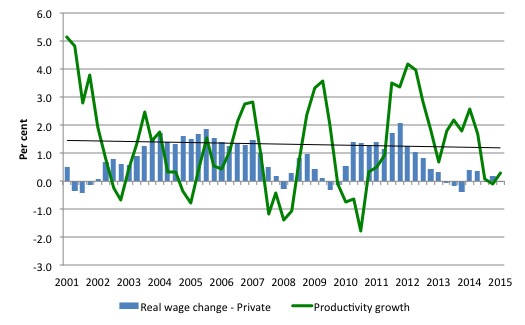

The next graph shows the annual hourly real wage change for the private sector (blue bars) and the annual hourly productivity growth (green line) since the March-quarter 2001. The black line is the trend productivity growth over the same time period.

Productivity growth has weakened in recent quarters after a few years of relatively strong growth.

Historically (for periods which data is available), rising productivity growth was shared out to workers in the form of improvements in real living standards. Higher rates of spending driven by the real wages growth then spawn new activity and jobs, which absorbs the workers lost to the productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

The neo-liberal period marked a shift in that relationship as we discuss below.

Clearly, since the September-quarter 2011, the payoff to workers from the positive productivity growth has been absent with real wages growth lagging productivity growth.

Real wages and productivity growth – a massive redistribution to profits

To understand the significance of the gap between real wages growth and labour productivity growth the following points should be noted:

- Employment is measured in persons (averaged over the period).

- Labour productivity is the units of output per person employment per period (in this case per hour).

- The wage and price level are in nominal units; the real wage is the wage level divided by the price level and tells us the real purchasing power of that nominal wage level.

- The total economy-wide wage bill is employment times the wage level and is the total labour costs in production for each period.

- Real GDP is thus employment times labour productivity and represents a flow of actual output per period; Nominal GDP is Real GDP at market value – that is, multiplied by the price level. So real GDP can grow while nominal GDP can fall if the price level is deflating and productivity growth and/or employment growth is positive.

- The wage share in national income (GDP) is the share of total wages in nominal GDP and is thus a guide to the distribution of national income between wages and profits.

- Unit labour costs are in nominal terms and are calculated as total labour costs divided by nominal GDP. So they tell you what each unit of output is costing in labour outlays.

- Real unit labour costs are calculated by dividing Unit labour costs by the price level to give a real measure of what each unit of output is costing. RULC is also the ratio of the real wage to labour productivity and through algebra I would be able to show you that it is equivalent to the Wage share measure.

From the last point, if real wages growth is above productivity growth then RULC are rising, which is the same thing as saying that national income is being redistributed to wages (workers).

However, if real wages growth is below productivity growth then RULC are falling, which is the same thing as saying that national income is being redistributed away from wages (workers) to profits (capital).

It can get a little more complicated if the share that government claims changes but that is normally stable, which means the dynamics of national income distribution are between wages and profits.

From the last graph, we can see that RULC have been falling and national income has been redistributed towards profits since September-quarter 2011 (with a one-quarter exception).

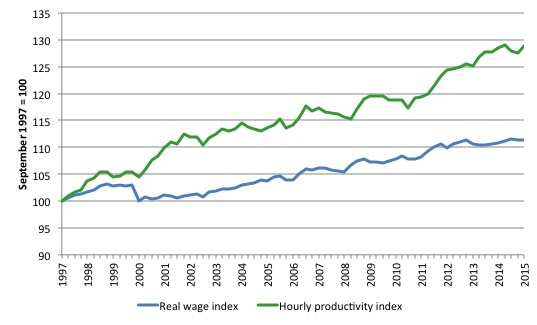

The following graph shows the indexed growth in hourly real wages and labour productivity per hour since the September-quarter 1997 (the start of the Wage Price Index series).

If I started the index in the early 1980s, when the gap between the two really started to open up, the productivity index would stand at around 180 and the real wage index at around 115.

Starting the index in the September-quarter 1997 produces a smaller gap, which just goes to show that one can manipulate data to achieve a range of ends (often quite contrasting) by altering the sample size.

What is clear is that since the September-quarter 1997, real wages have grown by only 11.4 per cent (so just over 0.6 per cent on average per year), whereas hourly labour productivity has grown by 28.9 per cent (or 1.7 per cent on average per year).

This is a massive redistribution of national income to profits and away from wage-earners and the gap is widening each quarter.

Where does the real income that the workers lose by being unable to gain real wages growth in line with productivity growth go? Answer: Mostly to profits. One might then claim that investment will be stimulated.

At the onset of the GFC (December-quarter 2007), the Investment ratio (percentage of private investment in productive capital to GDP) was 23.8 per cent.

It peaked at 24.3 per cent in the June-quarter 2013. But in recent quarters as the gap between real wages growth and productivity growth widens, the Investment ratio has fallen and in the June-quarter 2015 it stood at 21.8 per cent and falling.

The downward shift in the non-mining investment ratio is more stark than that.

Some of the redistributed national income has gone into paying the massive and obscene executive salaries that we occassionally get wind of.

Some will be retained by firms and invested in financial markets fuelling the speculative bubbles around the world.

For workers, the problem is that they rely on real wages growth to fund consumption growth and without it they borrow or the economy goes into recession. The former is what happened around the world in the lead up to the crisis (and caused the crisis).

The latter is more or less what is happening now.

One of the essential changes that needs to happen to ensure that another bout of financial instability doesn’t hit soon is that real wages have to grow in proportion with productivity growth – exactly the reverse of what is happening now.

Real wages growth and employment

Last week’s labour force data showed that employment had grown relatively strongly in the previous month (October 2015). With yesterday’s moderate wages data, many mainstream commentators are claiming that the employment response is the result of the suppressed real wages growth.

This is a standard mainstream argument that unemployment is a result of excessive real wages.

The problem with this explanation, when applied to the recent Australian experience, is that wages growth has been moderate for several years now while employment growth has been zig-zagging across the zero line over the same period.

Further, there are question marks about the veracity of last month’s labour force data and I suspect there will be revisions to that result in the coming months.

Finally, both the flat wages growth and the poor employment growth for the last several quarters are responding to the weak overall spending in the economy.

Firms will not employ new labour, no matter how cheap it becomes, if they cannot sell the extra goods and services that would be produced.

The claim that real wage cuts or growth retardation is necessary to stimulate employment is never borne out by the evidence.

As Keynes and many others have shown – wages have two aspects:

First, they add to unit costs, although by how much is moot, given that there is strong evidence that higher wages motivate higher productivity, which offsets the impact of the wage rises on unit costs.

Second, they add to income and consumption expenditure is directly related to the income that workers receive.

So it is not obvious that higher real wages undermine total spending in the economy. Employment growth is a direct function of spending and cutting real wages will only increase employment if you can argue (and show) that it increases spending and reduces the desire to save.

There is no evidence to suggest that would be the case.

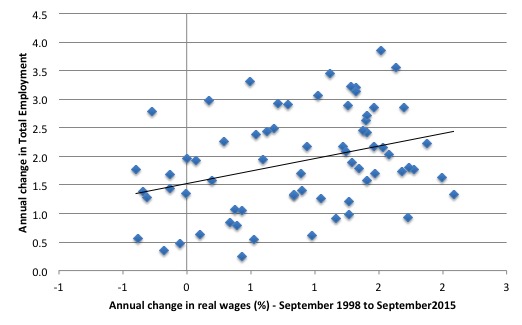

The following graph shows the annual growth in real wages (horizontal axis) and the quarterly change in total employment. The period is from the September-quarter 1998 to the September-quarter 2015. The solid line is a simple linear regression.

Conclusion: When real wages grow faster so does employment although from a two-dimensional graph causality is impossible to determine.

However, there is strong evidence that both employment growth and real wages growth respond positively to total spending growth and increasing economic activity. That evidence supports the positive relationship between real wages growth and employment growth.

Conclusion

Nominal wages growth is now at the lowest level since the data series began (September-quarter 1997).

Depending on how we measure inflation, real wages growth is slightly negative or slightly positive at present.

The slow wages growth is a cause and reflection of the slow growth in overall economic activity and employment. Workers are adopting a much more cautious approach to spending and firms will not lift the investment rate while sales are flagging.

The on-going subdued economic activity will also undermine the Government’s fiscal strategy, which can be summarised as squeezing net public spending out of the economy in the hope that in three years they will achieve a fiscal surplus.

That folly will be exposed. Economic growth will not be strong enough to match their assumptions and that means the growth in tax receipts will be less than assumed.

It would be better for the Government to stimulate the economy more now with larger fiscal deficits and then see the fiscal balance drop on the back of income growth.

Higher (and more reasonable) wages growth would both benefit from and provide support to such a fiscal strategy.

At the moment, we are in a race-to-the-bottom, which is nowhere any reasonable policy strategy should aim for.

Advertising: Special Discount available for my book to my blog readers

My new book – Eurozone Dystopia – Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale – is now published by Edward Elgar UK and available for sale.

I am able to offer a Special 35 per cent discount to readers to reduce the price of the Hard Back version of the book.

Please go to the – Elgar on-line shop and use the Discount Code VIP35.

Some relevant links to further information and availability:

1. Edward Elgar Catalogue Page

2. Chapter 1 – for free.

3. Hard Back format – at Edward Elgar’s On-line Shop.

4. eBook format – at Google’s Store.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Ok. Some Background..

I work in a small business that employs around 25 people.

Our income is from contracts with several large global corporations.

We have very little bargaining power when it comes to the rates we receive for our work or indeed the types of compliance embodied within those contracts.

Moreover, once the rate is agreed upon the corporations we contract with tend to shift the goal posts on a regular basis.

As such, we find ourselves swamped with administrative duties which were handled in house by these corporations. In addition, everything is expected to be done better and faster every year – and yet in real terms the rates paid to us for the work are falling.

I would doubt we are the only small business facing these problems.

Therefore if small business is at the mercy of corporations and corporations dictate the terms and conditions of contracts how on earth is it even possible for employers to support claims for wage increases ?

It’s ok to say that wages need to increase but without a solution it’s little mnore than jibber jabber.

Overall, I think small business is being screwed over just as much as the workers.

“The lessons have not been learned”. That is a statement of the bleeding obvious and not just in the economic sphere.

Australia is in the grip of a plutocracy of extraordinary greed,stupidity,ignorance and arrogance. They are ably supported by a “citizenry” who have an extraordinary disconnect from reality.Maybe there is a graph somewherer for all that.

I have no idea if there is a cure for this dis-ease. But if I was a gambler I would bet serious money on a fatal outcome.

Alan,

I see your problem and echo your concern. It has been policy for most big businesses for over twenty years now. Contract out and let the market discipline the contractors. Saves them the heartache of laying off workers and reducing remuneration. It’s extreme now…. even postal delivery drivers need to contract for business. Buying their own van, taking on the costs of insurance, vacation, retirement planning, sickness etc. Bet they wish they paid more attention in maths class now.

I don’t see solutions other than regulating markets and small businesses joining more powerful trade associations. Won’t happen unless the general population has a mass epiphany and recognises the dual edge sword of free market economics.

The complexity of these contracts… the lack of legal, actuarial and accounting expertise is such that an individual contractor will have little to no bargaining power. That is the whole point of the neoliberal exercise. A few niche opportunities will exist, some contractors will make good money, we will be told to stop complaining and be more like them.

Has the speculators share of GDP been accurately measured?

It would be interesting to see a graph containing the wage share,the profit share

and the speculators share (rise in assert price and derivatives)

the increasing inequality in wages is also a feature of the neo liberal period

so data about the wage share should always be nuanced by distribution.

Graphs showing the share of the 50th centile for wealth and income over time

would be very welcome.

Also with reference to the above commentators the profit share of GDP over time

has to be nuanced for changing distribution trends within the profit share.

“Therefore if small business is at the mercy of corporations and corporations dictate the terms and conditions of contracts how on earth is it even possible for employers to support claims for wage increases ?”

That’s why you have to have a strong government in place on your side. To take the rentiers and the oligarchs outside and have them figuratively shot.

Large businesses operate like centrally planned communist states. They are riddled with entropy and inefficiency, but keep going because competition isn’t sufficiently intense to expose those fault lines.

And of course they control ‘thousands of jobs’.

Yes aggregate individual income is occurring and that trend will only increase. It seems like an unresolvable problem until one cognites on the efficacy of what I believe is the next economic and monetary paradigm…monetary free gifting. I have absolutely no problem with more government so long as it is graciously sovereign and ACTUALLY places the freedom of its citizenry first. Paradigms are generalized ideas. Generalized Grace/graciousness is a better, more workable and more ethical idea to base a system on than power, profit and control

Let us have the philosophy and policies of the concept of grace as soon as possible.

Alan,

An unapologetic capitalist would say, “Welcome to capitalism. That’s competition.”

A Marxist would say, “This illustrates the natural tendency to monopoly under unregulated capitalism.”

These two statements, on their own, are correct and the explanations run into one another. They are both system explanations. They are saying it is the system and these are the natural results under a capitalist system with a low regulation regime.

It is worth reading this essay and then the (short) book of the same title;

http://monthlyreview.org/2011/04/01/monopoly-and-competition-in-twenty-first-century-capitalism/

There is a lot of empirical data indicating an increase in oligopoly and monopoly in this stage of capitalism. From your perspective as a small business capitalist-manager, I assume, you will have no incentive and no inclination to become a socialist. This is unless your firm collapses and you are ruined or become a worker again. In any case, the overall system isn’t about to be changed soon or easily. On the other hand, I would predict this system will collapse eventually but perhaps not in our lifetimes.

Carlos above has summed it up well. While the current system lasts and the current minimal regulatory regime lasts, the pressures towards monopoly power will continue. Small business needs to lobby, form associations, push for laws which regulate the monopoly power of big business and so on. Small business certainly has a case that much of what big business does is anti-competitive. Monopoly and monopsony are anti-competitive and do not meet the standard theoretically efficient economic model of many competitors with no one competitor holding undue market share.

“In economics, a monopsony (from Ancient Greek (mónos) “single” + (opsōnía) “purchase”) is a market form in which only one buyer interfaces with many would-be sellers of a particular product.

The microeconomic theory of imperfect competition assumes the monopsonist has market power and can influence terms of offer to its sellers, as the only purchaser of a good or service, much in the same manner that a monopolist can influence the price for its buyers in a monopoly, in which only one seller faces many buyers.” – Wikipedia.

That sums it up: “imperfect competition”.

However, good luck with trying to lobby against this state of affairs. Processes are still running in the other direction: i.e. to a system of even more monopoly power. The neoliberal minimisation of democratic government power is seeing even more power shifted to the corporate oligarchs, and their CEOs and Boards, of these corporate oligopolies and monopolies. We are currently heading towards a system of corporate dictatorship. We all need to work (and hope) to stop this process in time.

Ikonoclast,

I would assert that such opinions are merely restatements of orthodoxy. We need, we require a new idea, a new economic paradigm. No more mere economic theory. Look at the empirical data of scarcity of individual incomes in ratio to total costs/prices inherently created by the system, look at the history of this scarcity ratio playing out time and again in history, look at the present trends which are only going to make that inherent reality worse. Monetary Gifting must be integrated into economic theory. To hell with capitalism and socialism with their top down hierarchical enforced orthodoxies, we need a third way Distributism whose philosophy and reflective policies are a practical and ethical upgrade from such mereness.

OK wages are falling behind labour productivity. But what has happened to the returns on invested capital during the same period.

I think that is the first time I have heard Marxism called “orthodoxy” in the Anglophone spehere. I guess it depends on framing. You would have to describe or link to your version of Distributism. It seems a fairly broad church in terms of political economy ideology. It also seems to be linked to the Catholic Church.

Certain visions of Market Socialism, Marxist Autonomism and Worker Collectivism would all reflect aspects of Distributism and vice versa. Every self-employed person and every owner-manager-member of a single person or family business (where output and income are fairly shared), are already Distributists. Probably members of all equitable self-managed worker cooperatives are also Distributists. At this level it’s just which label you pick. You could pick “Distributism” or you could pick “Socialist Cooperativism”. Of course, this is all quite different from State Socialism which should be called State Capitalism anyway if on the old Soviet or Maoist model.

If we all go back to being small producers, there will be a marked drop in production. We will be much poorer in economic terms. One can make arguments for and against doing that including the issue of environmental sustainability. I think I would want an economic system which in some senses is as far from a mono-system as possible. For example, I think we need both small and large producers. Only large producers to date can make big machines, big structures and large infrastructure. All these are necessary now in the sense that our global population needs them to survive. Lower intensity production (which is what 100% small, piecemeal Distributist production will lead to) will not support this population. At the same time, I definitely do not support our current trend to massive corporate monopolies. Having said all that, we are growing towards the Limits to Growth so that is a real problem issue for us.

It’s fairly easy in a sense to implement Distributism or Worker Socialism for one-person to small enterprises. The issue becomes more difficult for large enterprises. But large worker cooperatives are possible. See Mondragon Corporation in Spain. Another issue is private property, public property and the state. There is no confict between private property and Worker Socialism. Any person can own all his/her non-income producing goods and chattels privately. Any person can also own his/her income producing assets privately or collectively. The collective can be still be private in the sense that it is worker-owned not state owned just as many current companies are share-holder owned not state owned. Worker collectivism per se simply removes separate ownership by shareholder capitalists and combines ownership and managership with workership.

The state as on overarching managing, directing and planning grouping remains necessary in my opinion. The state ideally must be fully democratic and immune to sectional interests which have extra wealth or other influence. Some state ownership remains necessary and beneficial. This is particularly in the arena of public goods like health, welfare and education and also in the arena of natural monopolies like roads, railways, communications, power and water utilities.

Now, if your vision differs from this then I probably won’t convince you and you probably won’t convince me.

Iknonoclast,

Thanks for the reply. The one thing capitalist and socialist theory have in common is they do not see that commerce/the economy itself is cost inflationary. They think that equilibrium or virtual equilibrium is possible without a supplement to individual incomes and a systemic mechanism for capturing and reversing inflated prices. Thus even worker owned and operated businesses will not be able to survive because the national and macro-economy will not be stable. I don’t wish to get into any long winded discussions about socialism versus Distributism. I readily acknowledge that socialism tends to be a more equitable system than capitalism. I in fact come out of a very progressive perspective, but missing the cost inflationary insight above I feel that socialism is still just a palliative not an actual solution to our deepest economic and monetary problems. The monetarily Distributist theory of Social Credit is actually an integration of the dynamism of capitalism and the ethical intentions of socialism that also correctly recognizes that the technological and AI trends are not going to enable either a Finance capitalist or socialist economy to function. It is a socialization of the money system so that the economy is actually functional. (and we do live in a monetary system not a barter one, and money is an excellent tool actually…if put to constructive purposes most especially the immanent freedom of the individual). Also, to me socialism still retains a little too much of the mentality of homo economicus. I’m more interested in humanity learning to live up to its actual species designation, homo sapiens, wise and discerning man.

As for its association with the catholic church, yes an order in Canada is actually dedicated to the promulgation of Social Credit. I’m as agnostic as one can be and an advocate of natural philosophy/natural spirituality so one doesn’t have to be a supernaturalist believer in pre-scientific dogmas to advocate it.

Neil genuine question what is the shooting of rentiers and ogliarchs a metaphor for?

What steps can a government take ?Or is this another job for the magic bullet?