The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Italian government is walking into the trap of its own making

On September 19, 2015, the Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi and the Minister of the Economy and Finance, Pier Carlo Padoan presented to the Italian cabinet (Consiglio dei Ministri) an updated fiscal (‘budget’) document – Nota di Aggiornamento del Documento di Economia e Finanza 2015 – which has received widespread attention in the media. The response to the update can be summarised in two statements: (a) the Italian government is abandoning austerity in the coming year and running an expansionary fiscal policy; and (b) the European Commission through the Ecofin (Committee of Finance Ministers) is showing admirable flexibility in allowing the Italian government to ‘relax’ their previous fiscal adjustment plan in order to safeguard economic growth. However, some commentators have challenged the notion that the September changes are indeed expansionary, pointing out that the fiscal deficit projected for 2016 might be higher than the earlier projections but is still smaller than the 2015 outcome. What should we make of all that? Well, neither assessment conveys what is actually happening.

The Italian government approved the changes on October 15, 2015.

Here are some of the press comments that followed the release of the updated fiscal statement.

On October 15, 2015, the UK Guardian article – Italy budget: Renzi risks Brussels battle – claimed that the fiscal changes approved by the Italian government “could put Rome in breach of austerity budget rules set by Brussels”.

The article also mentioned that “Brussels … warned the rightwing government … in Spain that proposals to relax austerity measures in its 2016 budget could be rejected”.

The UK Guardian article said that “the Brussels elite that wants Italy to take the opportunity of its recent recovery to step up fiscal tightening”.

The title of AAP article (October 15, 2015) – Italy goes for growth with expansionary budget – left nothing to interpretation.

We learned that the “Italy’s centre-left government on Thursday approved an expansionary budget designed to ensure a fledgling economic recovery takes wing in 2016”.

The Italian PM told the press that it was a “growth-orientated package”.

I discussed the shifting sands that are the opinions of Wolfgang Münchau with respect to the Eurozone in yesterday’s blog – The Eurozone – being ‘trapped in a dysfunctional monetary system’

On October 18, 2015, his Financial Times article – Better no fiscal union than a flawed one – argued that the current “dysfunctional monetary system” that is the Eurozone is preferable to “political integration of the wrong kind … the German variety”.

As evidence he wrote:

A good example of why the present system may be preferable to a bad fiscal union is Italy’s 2016 budget. It includes a much higher deficit than would have been the case under a rigid enforcement of the various fiscal rules because the European Commission interprets the rules more flexibly than before. This flexibility allows Italy to accompany its relative weak economic recovery with moderate fiscal expansion, which seems more or less appropriate. Under a German-style fiscal union regime, it would not have been able to do so.

So is the Eurozone getting all warm and friendly with respect to growth and starting to appreciate that the fiscal rules it has been imposing are the anathema to growth and unemployment reduction?

Equally, is the proposed changes to the Italian fiscal position expansionary, by which we mean increasing net government spending in 2016 relative to 2015?

Or is this talk of expansion a mirage designed to shore up political support for Renzi and gloss over the damage that the austerity in Italy is causing?

The revised fiscal plan (linked to above) indicates that the Italian government wishes to take advantage of the decision by the European Commission of January 13, 2015 to allow for a “more gradual fiscal consolidation as allowed by European treaties” (“La maggiore gradualità del consolidamento di bilancio è consentita dai trattati europei, come specificato dalla Commissione europea con la propria comunicazione sulla flessibilità del 13 gennaio scorso”).

Note a “more gradual fiscal consolidation” aka as ‘austerity-lite’ is not expansion.

Taking an opposite view was the EUNews article (October 5, 2015) – Bilancio, l’espansione restrittiva – which argued that the announcement by the Italian Minister of the Economy and Finance in September 2015 was a ruse.

The article rightly notes the ridiculous pursuit of a 5 per cent of GDP primary surplus by 2019 and discusses how that aim has been revised down in the latest fiscal plan to 4.3 per cent.

It also notes that the projected fiscal deficit in 2016 as a result of the changes announced in September 2015 is -2.2 per cent of GDP up from -1.4 per cent without any policy change and so the magnitude of fiscal consolidation is lessened and the balanced fiscal position is not reached until 2017 or sometime in 2018 rather than 2017.

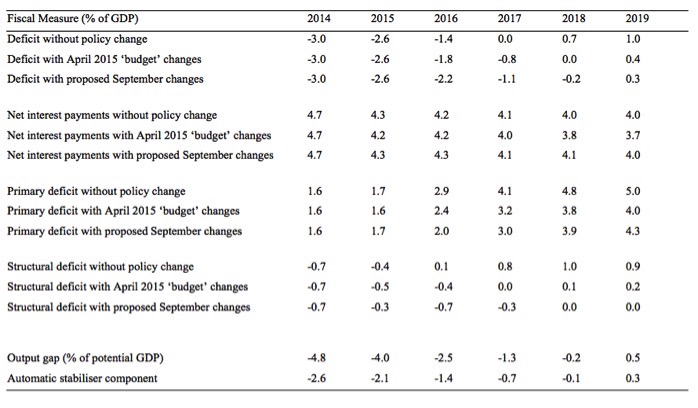

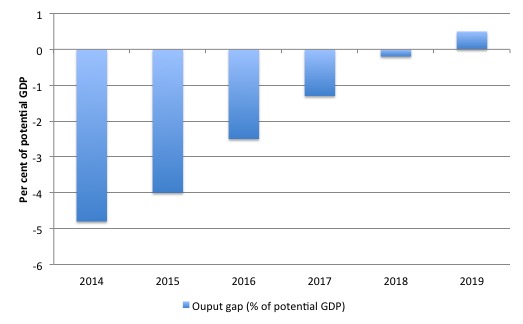

The following table presents the comparison data – from the outcomes that would have been expected to have occured without any changes to the fiscal policy parameters, to those which would have occurred had the April ‘budget’ policy announcements been implemented, and finally, to those which are expected to result from implementing the September policy announcements.

The Output gap and Automatic Stabiliser projections are based on the September 2015 policy scenario.

The EUNews article takes exception to the claim that the September changes signal an expansionary stance of the government.

The journalist contests the fact that the September projections for the deficit of 2.2 per cent are higher than they were without the proposed September policy changes can denote an expansive economic strategy (“espansiva la manovra economica”) is “strange way of reasoning” (“Ma è uno strano modo di ragionare”).

The journalist uses the example of a person who is drowning in a metre of water and then rises so they are only in half a metre – they are still drowning.

It is a poor example really because drowning is an absolute state whereas austerity is relative.

But you get the writer’s intention.

The EUNews writer correctly says that it “makes more sense to the deficit of 2016 with that of the year before” (“Ha più senso confrontare il deficit del 2016 con quello dell’anno prima, cioè l’anno in corso”).

So from the Table above, you can see that the projected deficit in 2016 under the proposed September changes is -2.2 per cent of GDP and the estimated deficit for 2015 is -2.6 per cent of GDP.

The conclusion the EUNews journalist reaches is that “the deficit falls by 0.4 points” and “In my day (that is, when Keynesian macroeconomics was dominant) this would be called a tightening”.

I beg to differ.

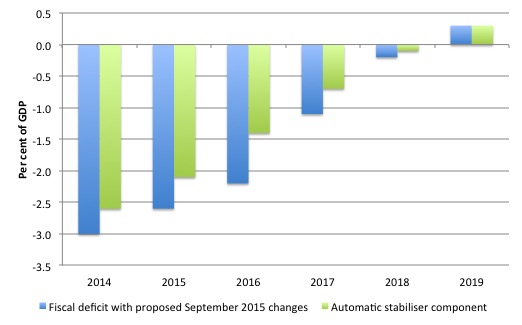

First, the following graph shows the movements in the overall fiscal balance from 2014 (actual) to 2019 (where the 2015-19 figures are estimates).

The three colours indicate the three states – no policy change in the current fiscal year, the policy changes projected in the April 2015 ‘budget’ and the most recent September 2015 variations.

So clearly the rate at which the overall fiscal balance contracts is decreased as a result of the proposed September 2015 policy changes.

And the 2016 outcome is projected to be lower than the 2015, which, in turn, is projected to be lower than the 2014 outcome.

So the conclusion is that based on these projections the net contribution of government fiscal policy to total spending and, hence, economic activity is consistently falling over the forecast period.

Is that QED for the EUNews contention? I am afraid not.

As background, please read – Structural deficits – the great con job!.

Remember that the overall fiscal balance (which is shown in the previous graph) is the difference between total government revenue and total government outlays.

So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the fiscal balance is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting. However, this fiscal balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the fiscal balance is in surplus we conclude that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the fiscal balance is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

This is certainly the sense in which the EUNews journalist is operating.

However, the complication is that we cannot then conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty is that there are so-called ‘automatic stabilisers’ operating.

To see this, the most simple model of the fiscal balance we might think of can be written as:

Fiscal Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Fiscal Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the fiscal balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the fiscal balance will vary over the course of the economic cycle.

When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the fiscal balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit) without any policy changes.

Conversely, when the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the fiscal deficit falls or the surplus increases.

Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the economic cycle by expanding the deficit in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So the fact that the fiscal deficit contracts from one year to the next doesn’t necessarily allow us to conclude that the government has suddenly become of an contractionary mind.

Similarly, a rising deficit doesn’t necessarily indicate an expansionary policy stance.

In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome that problem, economists use the so-called ‘structural balance’ which has the cyclical components (the automatic stabilisers) netted out.

In effect, it is an attempt to measure what the fiscal balance that would be if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the fiscal position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminates the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So the structural fiscal outcome would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the structural balance is in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of fiscal policy is contractionary and vice versa if the structural balance is in deficit at full capacity.

If we observe a decreasing structural deficit then we can conclude the discretionary fiscal stance is contractionary and if we observe an increaseing structural deficit we can conclude the discretionary fiscal stance is expansionary, irrespective of what is going on with the overall fiscal balance.

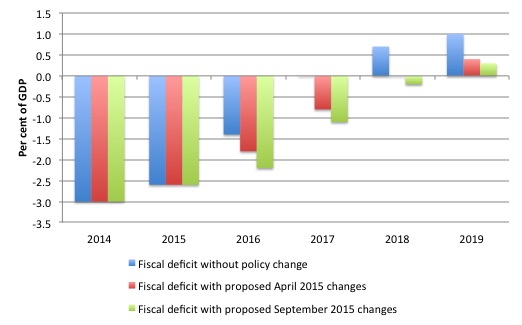

The next graph shows the projected structural deficits (as per cent of GDP) under the three scenarios outlined above. The data is also available in the Table above.

You can see that the projected structural deficit rises from -0.3 per cent of GDP in 2015 to -0.7 per cent of GDP in 2016, which signals that discretionary fiscal policy in Italy is planning to be expansionary even though the overall fiscal outcome reduces the net contribution of government spending over those years.

How do we explain that?

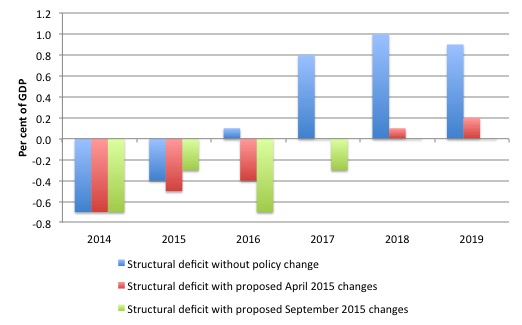

The next graph shows the projected output gap (as a percent of potential GDP) out to 2019. You can see that the gap is projected to shrink rather dramatically between 2015 and 2016 as a result of the strong projected real GDP growth that the expansionary policy stimulus is intending to have.

More about that later.

The next graph shows the actual projected fiscal outcome (blue bars) and the projected cyclical (automatic stabiliser) component (green bars).

The difference between the two bars is the structural deficit.

It is clear that the cyclical component shrinks very quickly – also due to the assumption that real GDP growth will be very strong and tax revenue will rise strongly in 2016.

So the Italian government is trying to suggest that a very modest discretionary stimulus (the rising structural deficit) will have such powerful growth effects that the rise in tax revenue (3.6 per cent) will outstrip the rise in government spending (1.1 per cent) over the year to 2016 and that is why the overall fiscal deficit shrinks.

But it is being driven by the expansion in the structural deficit over 2015 and 2016.

The real story

The overall projections presented in the September document are quite bizarre and I suggest will not go close to being realised.

The real GDP growth estimates in particular are totally unrealistic.

The base all their projected fiscal outcomes on the assumption that real GDP will rise from -0.4 per cent in 2014 to 0.9 per cent in 2015, then 1.6 per cent from 2016 through to 2017 and then 1.5 per cent in 2018 and 1.3 per cent in 2019.

These optimistic projections are driven by rather massive increases in expected private investment.

Can we just suggest that none of that will happen and the improvement in tax revenue will be lower than expected.

Which means that the deficit will be larger than estimated and then the fun will begin. Sorry to think that the evil interventions from Brussels is ‘fun’ – it was turn of phrase.

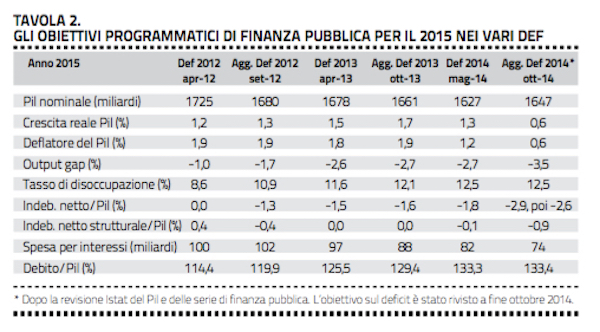

The following Table shows degree to which the official real GDP forecasts are revised in successive fiscal statements.

So in April 2012, they forecast real GDP growth (Crescita reale Pil (%)) would grow by 1.2 per cent. They progressively altered that projection as reality overtook their optimism and by October 2014 the projection had been halved.

Conclusion

The fiscal changes announced in September are expansionary because the projected structural deficit is rising. But I would take the figures with a grain of salt.

The real problem is that the European Commission will be watching over this process as it unfolds and congratulating itself on being ‘flexible’ for allowing a one-off rise in the structural deficit and an easing of the austerity.

But come next year when the projected growth is less than expected and the fiscal balance overall rises, the technocrats will be forcing even harsher austerity onto the government on the basis that the discretionary fiscal expansion was futile.

By playing this game of optimistic growth forecasts (something they probably copied off the IMF!), the Italian government is walking into a trap – of its own making. Check WeeklyAds2.

The fact is that the output gaps are much larger than projected and a much larger discretionary fiscal stimulus is required. But then that would blow the fiscal outcome off the Stability and Growth Pact radar and Brussels would send in the ‘troops’ (the ‘bean counters) – or divert some from Athens.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

One solution to individual countries running larger deficits than the EZ authorities approve of was suggested recently by Dijsselbloem. He said: “There could be merits in having a big European sister of national fiscal councils, placed outside the Commission.”

Of course that means even more loss of sovereignty for individual EZ countries, but they all seem keen on that famous “ever closer political union”, so what would they have to complain about?

That’s not strictly accurate. The GDP growth anticipated by the forecasters actually INCREASED through 2012 and 2013, and it wasn’t until 2015 was breathing down their necks that they were forced to revise downwards. Which suggests, as you imply, that a major part of the strategy being followed is to ignore reality for as long as possible, in the hope that “something” will turn up.

@Ralph Musgrave

That is an absolutely bizarre interpretation of Dijsselbloem’s speech. He quite clearly wants to centralise power in an unelected entity that will then be able to enforce austerity. This is not a “solution to individual countries running deficits than the EZ authorities approve”. Rather it is the formalisation of the toxic Eurogroup in EU law. Here is the full quote with all the context intact:

“Safeguarding this buffer – and keeping our public finances on a sustainable footing calls for transparent compliance with and enforcement of the budgetary rules: the Stability and Growth Pact is our anchor of confidence as Mario Draghi always says and we need to adhere to the rules. The Commission’s role is crucial here. The Commission has the instrument to make sure the fiscal rules are applied and if necessary it must use it. There is a big difference between a political Commission and a politicised Commission. Let me explain. The Commission as in the college of commissioners, is a political body. But I feel but the assessment of the national draft budgetary plans should be done in a technical way and not in a politicised way. For that reason there could be merits in having a big European sister of the national fiscal councils, placed outside the Commission to provide independent assessments of the national draft budgets, on the basis of which the Commission gives its (political) opinion. I think this is the right approach.”