The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Eurozone battle lines being drawn again with Germany on the other side

The battlelines between the European Commission and France and Italy over the – Corrective arm – of the Stability and Growth Pact are firming up after the Italian Government publicly released a ‘strictly confidential’ letter from the Vice President of the European Commission – La lettera della Commissione Europea all’Italia – on the homePage of the Ministry of Economy and Finance late last week. The European Commission expressed hostility towards the Italian government hinting that there was a lack of trust involved. Nothing could be further from the truth. The fact is that the Commission wants to keep its dirty work away from the public eye because it knows that deliberately creating unemployment and poverty is not exactly an endorsement for its common currency model. But this little skirmish last week between the technocrats and the Italian government is just part of a war that is to come over the implementation of the Excessive Deficit Procedure in both France and soon, Italy. We have been here before – 2002-03 – but this time, Germany was in the trenches with France. Now it is playing the role of the enforcer. It all goes to show however, if we ever needed reminding what a sorry, failed enterprise the Eurozone actually is.

The letter was published under the heading “Highlights” (“In Evidenza”) and the summary notes that:

In light of the Italian plan, which provides for the temporary deviation from the path of achieving the medium-term objective (MTO), the Commission has asked Italy for additional information that more clearly outlines the reasons and the assumptions.

(“Alla luce del piano italiano, che prevede la deviazione temporanea dal percorso di raggiungimento dell’obiettivo di medio termine (MTO), la Commissione ha chiesto all’Italia informazioni aggiuntive che ne chiariscano le ragioni e i presupposti”)

Recall that the so-called Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) is a technical process and is triggered if a Member State has either:

1. “breached or being in risk of breaching the deficit threshold of 3% of GDP or”

2. “violated the debt rule by having a government debt level above 60% of GDP, which is not diminishing at a satisfactory pace. This means that the gap between a country’s debt level and the 60% reference needs to be reduced by 1/20th annually (on average over three years).”

The EU notes that:

Special consideration can be given to countries whose fiscal positions have worsened due to exceptional events outside their control, such as in the case of natural disasters or as a result of a severe economic downturn, but under the double overarching condition that the excess over the deficit is close to the reference value and temporary.

Hence the wording of the Italian Ministry regarding their so-called “temporary deviation”. They are clearly trying to appeal to the special consideration component of the EDP.

On June 26, 2013, the European Council published this decision with respect to Italy under Article 126(12) of the Treaty – Council decision abrogating the decision on the existence of an excessive deficit.

The Council had previously (December 2, 2009) followed the Commission’s recommendation that an excessive deficit existed in Italy. At the time (2009), the fiscal deficit was 5.3 per cent of GDP and the public debt ratio was 115.1 per cent, so well outside the rules.

By 2012, the Italians had reported a deficit of 3 per cent of GDP and the Council noted that “The improvement was driven by significant fiscal consolidation” – in other words, growth and employment damaging fiscal austerity.

They also noted that:

… 2012 interest expenditure was 0,8 percentage point of GDP higher than in 2009 and the composition of economic activity was tax poorer.

Ringing any bells?

The rising interest expenditure and the declining tax revenue was directly related to the damaging effect that fiscal austerity had on economic growth.

The former because public debt rose and the latter because employment dropped.

In making their 2013 decision to abrogate the EDP against Italy, the Council accepted forecasts that the Italian fiscal deficit would “decline slightly to 2,9 % of GDP in 2013 and then fall to 1,8 % of GDP in 2014.”

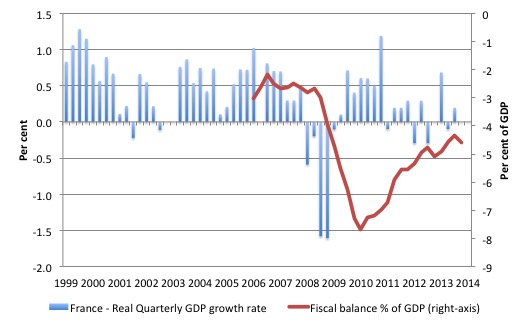

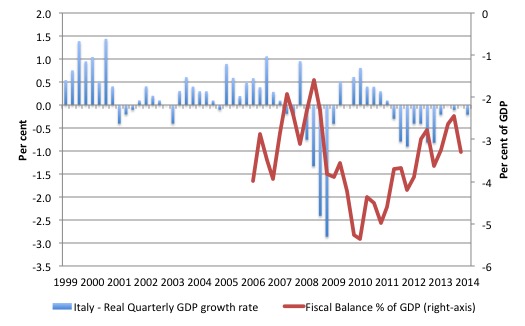

What happened? The obvious. The following two graphs (France first, Italy second) show the quarterly real GDP growth rate from 1991Q1 to 2014Q2 (blue bars – left-axis) and the 6-quarter moving average of the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP (red line – right-axis). I used the moving average to smooth out the seasonally unadjusted data available from Eurostat for the quarterly public finance data.

The patterns are very similar although the malaise facing Italy is worse (but that is relative to France which is terrible).

The plunge in growth rates as a result of the GFC were arrested finally because the fiscal deficits rose substantially – injecting much needed public net spending into the respective economies that helped (but did not fully) offset the decline in private spending.

Had the ECB announced it would fund those deficits until growth had stabilised and private debt levels had been reduced – given the recession was what we call a balance sheet recession – see blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy J – the Eurozone crisis would have been short-lived.

The previous conclusion assumes the ECB funded all Member-State deficits accordingly.

You can also see that the growth was helping to reduce the fiscal deficits as a proportion of GDP, the usual situation. This occurs because as growth resumes and economic activity including wage employment starts to recover, tax revenue rises and welfare outlays fall. The so-called operation of the automatic stabilisers.

This is why it is nonsensical to target a particular public deficit ratio (with respect to GDP) because it is so sensitive to private economic activity. The government cannot actually guarantee it will hit a particular outcome given that private spending essentially dictates the outcome.

The government is far better off targetting employment levels to ensure there are enough jobs available and to also work to ensure first-class public infrastructure is in place.

Whatever the fiscal outcome that emerges from that sort of quest will be appropriate, given the goal of government is to advance welfare rather than achieve some abstract financial ratio, which few people fully understand anyway.

The situation changed dramatically in 2009-10, as the European Commission and Council started to mindlessly apply the Excessive Deficit Procedures.

The imposition of the mindless fiscal rules, which were part of the overall failed design of the monetary system in the first place, stopped that growth in its tracks.

As hard as each country tried to reduce their deficits with discretionary cuts in net spending the more they oversaw slowing growth and then a return to negative growth.

In Italy’s case, the situation is approaching a catastrophe. The Italian economy hasn’t seen positive growth since the September-quarter 2011 and it is now some 9.2 per cent below its first-quarter 2008 peak GDP levels.

That is a massive amount of real income to deliberately sacrifice.

And, of-course, their fiscal position is still in breach of the rules and is deteriorating again as the negative growth continues.

Regular readers will know I don’t automatically use the term deterioration to describe an increasing fiscal deficit. I differentiate between good and bad.

The national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no overall spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal. It will be whatever is required to ensure there is enough spending in the economy to generate sufficient jobs to satisfy the preferences of the workers for work.

However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a budget surplus will be possible.

But the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the budget outcome towards increasing deficits.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs).

But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The budget will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call “bad” deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with ‘good’ deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

You might like this blog from the past – A voice from the past – budget deficits are neither good nor bad.

In that context, the deficits in France and Italy are at present ‘bad’ because they are being sustained by the deliberately created recessed states and entrenched mass unemployment.

The letter published by the Italian government was part of the new process under the so-called Fiscal Compact which allows Brussels to vet Member State fiscal plans in advance of them being legislated by the relevant national governments.

Last week the European Commission told five nations – Austria, France, Italy, Malta and Slovenia – that their fiscal proposals would be unacceptable. And Italy’s response was the publication of the letter.

Currently, there are 8 Eurozone nations in on-going excessive deficit procedures – Malta, Cyprus, Portugal, Slovenia, France, Ireland, Greece and Spain.

Add Italy and Austria and that makes 10/18 nations caught up in the ridiculous bureaucratic procedure, which only kills growth and prosperity.

Interestingly, the outgoing European Commission boss José Manuel Barroso then became engaged in a slanging match with the Italian prime minster Matteo Renzi at the European Union Summit in Brussels last weekend.

Barroso told the media that:

Regarding the letter from vice-president Katainen yesterday, sent to his Italian colleague, the decision to publish it on the website of the ministry of finance is a unilateral decision by the Italian government. The Commission was not in favour of the publication because we are continuing consultations with various governments. These are informal consultations and in some cases they are quite technical, and we think it’s better to have this kind of consultations in an atmosphere of trust. But the Italian government contacted the Vice President Katainen telling him that he would publish the letter and of course we do not object to the publication, it is their right, but again, this is not true it is the Commission which pressed the government to publish the letter. If we wanted to publish it, the Commission could publish the letter itself.

One wonders what the European Commission has to hide. What would be the motivation in keeping this sort of communication private – that is, away from the public eye? Probably the obvious. Social conditions in Italy are deteriorating as the economy continues in its recessed state with no much prospect of growth any time soon, especially with Germany now nearing recession.

For his part, the Italian PM responded by claiming that the:

… the days of secret letters are over in this building. With Italy, open data will be total. We want everything to be clear with Brussels because it is the only way for citizens to understand . It’s just he beginning. Turning over a new leaf, after next week we ask that any sensitive data that commission sends should be published.

The real drama is going to centre on France however because they are already in an EDP and must correct their fiscal position to accord with the rules by 2015.

Unless the French government is prepared to accept a major recession returning there is not much chance it will make the proposed targets.

Then we will have No 2 and 3 (in size) caught up in the EDP and Germany is not immune given its growth rate is approaching zero and sales for production output are drying up.

We have been in this position before. Go back 12 years and this time it was Germany and France that were the ‘culprits’.

After years of negotiating the SGP and the EDP, in particular, trouble emerged for the EMU almost immediately. Given the poorly conceived nature of the SGP it was no surprise that it would fail its first test.

What was surprising was the way the politicians and bureaucrats behaved in the face of what any reasonable assessment would consider to be extraordinary hypocrisy.

By early 2002, the German economy was slowing quickly and the Commission concluded that it was likely that Germany would “require a substantially higher adjustment effort” to achieve the projected fiscal balance by 2004 – see Commission assesses the German Stability Programme Update (2001-2005).

On January 30, 2002, the Commission, acting under the EDP rules, proposed “to give Germany an early warning on the basis of Regulation 1466/97 of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)”, which would be forwarded to the Ecofin Council for its determination.

At the Ecofin meeting on February 12, 2002, the Finance Ministers concluded that Germany’s “new update broadly complies with the requirements” (European Commission, ‘6108/02 (Presse 28)’, 2407th Council meeting, ECOFIN, Brussels, 12 February 2002)

The Council also claimed that Germany was expected to record a balanced fiscal position by 2004. The risk was that economic growth would fall and the automatic stabilisers would push the fiscal balance “even closer to the 3% of GDP reference value”.

The Council clearly understood that any further slowdown in the German economy would generate a larger deficit. But it still demanded, “a balanced budget position must be reached as soon as possible”.

For these technocrats the rules were binding and Germany would be cited under the EDP if they didn’t bring its deficit below the 3 per cent reference value. The likely impact on unemployment and the prosperity of the German population of the enforced austerity at a time when the economy was weak was disregarded.

The Council also urged Germany to ensure there was a “decisive implementation of structural reforms … in particular in the labour market and in social security and benefit systems”.

The neo-liberal mindset was thus firmly in place despite the obvious risk that Germany’s insipid growth would falter under the intensified fiscal austerity.

The Council determined that the German government had “effectively responded to the concerns expressed” (by promising more fiscal austerity than previously indicated) and the EDP was closed.

At the same Ecofin meeting, the case of France was also considered. A similar narrative was recorded: downside risks of low growth pushing out the deficit; the need to be in balance or surplus by 2004; more fiscal austerity promised by the French government; the need for more cuts “as soon as possible” in the pension system.

But there had been no ‘early warning’ issued to France and so no further determination was deemed necessary.

German growth had stalled completely by the end of 2002 as it tried to reign in its fiscal balance to meet the SGP rules.

However, worse would come as the economy moved into recession in 2003. German unemployment, already high in 2001 at 7.9 per cent, rose to new heights over the next four years: 8.7 per cent in 2002, 9.8 per cent in 2003, 10.5 per cent in 2004, and finally peaking at 11.3 per cent in 2005.

This was all down to the mindless fiscal austerity that Germany adopted within the recession-biases of the SGP. Millions lost their jobs as a result, while others increasingly found their jobs becoming more precarious and their wage prospects suppressed.

If there was ever a time for reflection on how damaging the EMU structure could be, then this period should have been it.

On November 19, 2002, the Commission again reported on the ‘Excessive deficit on Germany’. It noted that Germany’s projected fiscal deficit for 2002 would rise from 2.8 per cent of GDP in 2001 to 3.8 per cent and “therefore, the deficit will exceed the reference value of 3% by a significant margin” (see Report from the Commission, Excessive deficit in Germany’, Report prepared in accordance with article 104, paragraph 3 of the Treaty, SEC (2002) 1245 final, Brussels, November 19, 2002).

In addition, its public debt ratio was expected to exceed 60 per cent of GDP and would also breach the SGP threshold. As a consequence, the Commission initiated the EDP against Germany for its “budgetary slippage”.

The ‘slippage’ was due to the recession and the need to expand the fiscal deficit to ensure final spending in the economy was sufficient to arrest the decline.

But for the Commission, the ‘slippage’ was defined solely in terms of the ‘reference values’, which were the only targets they focused on.

The Commission explained the “very weak” growth in terms of the decline in the construction sector as a result of the end of the reunification process, “numerous structural impediments … inflexible labour market” and its welfare system.

None of these things caused the move into recession.

A responsible government would have realised the reunification construction boom would end and there would be a need for alternative forms of stimulus, given the high propensity of its population to save. But trying to live within the SGP rules forced the government to withdraw any form of spending support for its economy.

The ‘structure’ of the economy had nothing to do with it – Germany had grown at much more robust rates with this ‘structure’ in the past. The only fundamental ‘structural’ change that was impacting growth was the imposition of the inane EDP mentality.

The terminology used in the Commission’s reasoning was mindboggling. They acknowledged that “budgetary developments have been adversely affected by continued weakness of economic activity” plus a one-off flood but “in the sense of the Treaty” the deficits could not be considered “outside the control of the German authorities, nor … the result of a severe economic downturn”.

The German authorities could have cut its net spending more harshly but growth was already stalling and unemployment was rising quickly.

From outside the twisted neo-liberal Groupthink, the downturn was already severe. But the SGP defined the threshold of severity as a decline in real GDP of more than 0.75 per cent in any year.

This definition was totally arbitrary, like all the other SGP reference values, which meant that millions could lose their jobs without a downturn being defined as severe.

At any rate, the game was on. Germany was now caught up in the trap it had set for Italy, Greece and other ‘suspect’ nations. The Commission upped the ante on January 8, 2003 in its – Commission opinion on the existence of an excessive deficit – when they concluded that there was an excessive deficit in Germany and accused Germany of not respecting the Treaty (see Commission recommendation for a Council decision on the existence of an excessive deficit.

They demanded that Germany “put an end to the present excessive deficit situation as rapidly as possible” by cutting net spending and retrenching its labour market protections and welfare system.

The Council accepted this conclusion a few weeks later and demanded that Germany cut its deficit by 1 per cent of GDP within four months. Had this very large fiscal contraction been successful, the recession in Germany would have deepened with disastrous results.

There was also no guarantee that the changes would have reduced the deficit anyway given the loss of tax revenue as economic growth faltered.

The German economy contracted in 2003 and the fiscal balance rose to 4.2 per cent of GDP up from 3.8 per cent in 2002.

On November 18, 2003, the Commission recommended to the Council that Germany be declared ‘non-compliant’ under the EDP, which would require much harsher cuts and fines – see Recommendation for a Council Decision giving notice to Germany, in accordance with Article 104(9) of the EC Treaty, to take measures for deficit reduction judged necessary in order to remedy the situation of excessive deficit.

The Commission’ statement rehearsed the myth of a ‘fiscal contraction expansion’, which has featured prominently in the current crisis. They claimed that a substantial fiscal reduction would not:

… necessarily depress economic activity. A lack of private confidence is a key factor holding back growth … [and that] … current high saving rates … suggest that … present income levels are no serious constraint for private consumption. Indeed, consumption is being held back by high uncertainty.

This was pure neo-liberal dogma and contrary to evidence.

The Commission failed to mention the growing angst in Germany over the Hartz reforms that had been introduced in early 2003.

The rising unemployment associated with the forced fiscal contractions and the increasing attacks on real wages associated with the Hartz reforms had undermined consumer confidence.

With further fiscal contraction expected, and worsening unemployment there were no coherent reasons for consumers to reverse their saving plans and undertake a spending spree.

Further, without strong growth in consumption spending, firms could satisfy current sales with the existing capacity and therefore had no imperative or incentive to increase investment. Most firms formed the view that the economy would deteriorate over the next 12 months and yield very little profitable investment opportunities.

Later in its recommendation, the Commission actually acknowledged that “prolonged stagnation” was more likely for Germany as it sought to cut its deficit and as a consequence it extended the deadline for the correction of the ‘excessive deficit’ by one year to 2005.

As has been the case throughout this saga, it was a case of the blind ideological adherence to the rules coming up against the obvious facts that could not be ignored. The rules were once again being ‘bent’, as they had been during the convergence process, and, as they would be later, when the really big crisis hit.

A parallel process had been going on with respect to France. The detail was very similar to the German case – economic downturn, fiscal deficits rising beyond the SGP reference values, enforced austerity, worsening growth and deficits, the technocrats mindlessly applying their rules.

On March 28, 2003, the Commission published a report on the French situation and on October 8, 2003, the Council determined that France was not responding adequately to its demands for fiscal retrenchment.

A major showdown was looming.

As is now, the French government was publicly hostile to the process. The problem was that the fiscal rules embedded in the SGP were ‘written in marble’ despite the protestation to the contrary from the French Minister for Economic Affairs, Finance and Industry, Francis Mer in June 2003.

The nations had all signed up to a discipline that they found impossible to maintain if they were to meet their responsibilities to maintain domestic growth and reduce unemployment.

It was obvious that the rising deficits from 2001 were the result of the on-going poor real GDP growth, which had been exacerbated by the need for fiscal convergence as part of the move to the common currency.

The political reality was that the prosperity of the EMU had been suppressed for years in the race to meet the convergence criteria and there was only so much austerity that could be tolerated by the respective populations.

Further, most of the EMU nations had resorted to a range of ‘once-off’ accounting tricks to render their fiscal balances consistent with the criteria. Once business as usual was resumed, the fiscal balances began to more closely resemble the underlying economic growth realities of the nations, which were largely inconsistent with the rigid SGP fiscal rules.

On Bastille Day 2003, the Ecofin Ministers met in Paris to consider deficit situation. French President Jacques Chirac had pressured them to relax the fiscal rules to allow some room for growth.

The hostility among the other EMU partners towards the French call for an easing of the SGP was evident in the reported anger from Dutch Finance Minister Gerrit Zalm who said (see Chirac’s budget plea creates EU storm):

This is July 14, the day the Bastille was stormed, and now it’s the day the stability pact has been stormed. The storming of the Bastille was a better idea.

But Germany knew it had the ally in France that it needed to ignore the Commission and manipulate the Council when it came to the crunch later in 2003.

Even so, the Germans still tried to have it both ways. The German Finance Minister Hans Eichel told the press on July 14, 2003 that (from BBC report cited above):

Stability is not the priority right now … we need growth.

But then claimed that Germany was not calling for a relaxation of the rules. The inevitable Franco-German collusion on the deficit question later in 2003 would plunge Europe into crisis.

In late August 2003, the French Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin was in Brussels for a European Commission meeting. He called for more flexibility in the application of the SGP. There was fierce resistance within the Commission to this idea.

Raffarin said his priority was growth and employment – a similar line being pushed by the French government now.

On September 4, 2003, Raffarin continued this sentiment during an interview with French television station TF1, which the Le Monde editorial on September 6, said had demonstrated contempt for Europe. Raffarin said that while the SGP was “important” his “first duty” was to ensure there is work for the French and that he was not going to compromise that for some “accounting equations and to do some maths” to satisfy the bureaucrats in Brussels. He also said that France would not follow Germany into austerity.

Note that as Barroso was castigating the Italians for releasing the letter, the Italian PM told the Italian Parliament last week that Italy would not bow to:

… diktats from the outside …

The crisis point to the 2002-03 saga came in November 18, 2003 when the Commission recommended to the Council that the response of both the French and German governments to their earlier demands was inadequate under the terms of the Treaty and that further action under the EDP be triggered and a much tighter frame be required for resolution.

The stakes were now high. The Commission wanted both France and Germany to be sanctioned for their obdurate behaviour with respect to the rules.

One should emphasise that by not implementing the scale of the fiscal cutbacks recommended by the bureaucrats, the French and German governments were, at least, saving some jobs from destruction, amid the millions that were being retrenched as a result of them playing the game ‘somewhat’.

Five days later, the Finance Ministers met in Brussels to vote on these recommendations. Under the Treaty, it was Ecofin who oversaw the process, which was laid out as follows: the Commission was responsible for the surveillance system of Member State fiscal positions and would make recommendations to Ecofin if it considered there was an excessive deficit under the rules.

Ecofin would then determine whether that was the case or not and if it decided that there was an excessive deficit, it would require the offending nation to fix the problem within a short time period. If after that time, the excessive deficit persisted then Ecofin could impose the very harsh fine.

Further, decisions taken by Ecofin are determined by the quaint construct called a ‘qualified majority’ (or supermajority), which is a weighted voting system such that the larger nations by population are given more weight (votes) in the process. The aim was to balance the interests of small and large member states.

However, the system effectively meant that the ‘big police’ were able to derail any investigations against them through collusion. The weights used in the 2003 were established in the Treaty of Nice, which came into force on February 1, 2003.

They have been updated over time as more nations have joined the European Union and the system is now less vulnerable to the so-called ‘blocking minority’ (now requiring at least four states to be included in the bloc).

In November 2003, there were 87 ‘votes’ in total allocated to the 15 EU nations with Germany, France, Italy and the UK each having 10, Spain 8, Belgium, Greece, Netherlands and Portugal 5 each etc. A qualified majority amounted to 62 votes out of the 87 (71.3 per cent) and 26 votes (29.9 per cent) constituted a blocking minority. So Germany and France only had to do a deal with the UK or Italy, for example, to run the show in their favour (European Commission, 2012b).

The upshot was that the Ecofin Council rejected the crucial Commission recommendations in relation to both France and Germany.

While a simple majority was achieved for each vote, attracting affirmative responses from Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Spain, Netherlands, Austria, Finland and Sweden or a subset where only Eurozone nations could vote, a qualified majority failed and no decision was adopted – see Council Press Release, 14492/1/03 REV 1 (en) (Presse 320).

The Council determined that while it had found that an excessive deficit existed in France and had recommended that nation take appropriate measures to reduce the deficit by the end of 2004, there had equally been several “important economic and budgetary developments” (slower growth and rising unemployment) evident in the third-quarter of 2003 which influenced its final conclusion.

Accordingly, it decided that it would not act against France “at this point in time” and would hold the EDP against France “in abeyance for the time being”.

The same reasoning was applied to Germany. The Council had not only ignored the recommendation of the Commission, but also suspended any action under the EDP against France and Germany.

The Commission was furious with the Council’s decision to let France and Germany off the hook and accused it of not providing an “adequate explanation”. It felt compelled to enter the following statement in the official minutes of the Ecofin meeting:

The Commission deeply regrets that the Council has not followed the spirit and the rules of the Treaty and the Stability and Growth Pact that were agreed unanimously by all Member States. Only a rule-based system can guarantee that commitments are enforced and that all Member States are treated equally.

The Commission will continue to apply the Treaty and reserves the right to examine the implications of these Council conclusions and decide on possible subsequent actions.

Where did that leave the whole enterprise? The UK Guardian article (November 27, 2003) – What is the stability and growth pact? – reported soon after the Council had suspended the SGP that:

Economic stagnation in France and Germany has scuppered the budgetary constraints put in place with the euro.

It also said the Council decision to ignore the Commission’s recommendation had put the SGP into “intensive care”.

Overall, the decision reflected the recognition that “imposing financial penalties when they’re already mired in economic problems made little sense”.

While that is a correct summation, the reality is that it was only because France and Germany were the targets of the action that this sort of recognition came to the fore.

It clearly hasn’t been a consideration in the case of Greece in 2010 and onwards. On November 27, 2003, Ed Crooks and

Ed Crooks and George Parker wrote in the Financial Times article (November 27, 2003) – ‘The growth and stability pact may not be mourned by many but the eurozone needs fiscal discipline’ that:

France and Germany won: they usually do. But the European Union is assessing the damage of a joyless victory, secured in the small hours of Tuesday morning, that did much more than shred the EU’s fiscal rulebook … The message was clear. The European Union has rules, but not everyone has to obey them. France and Germany, long seen as the driving force behind European integration, looked more like a pair of playground bullies (Crooks and Parker, 2003).

The ramifications were clear. The rules would have to be renegotiated. But before that process would begin, the “subsequent actions” noted in the Commission’s qualifying statement in the Ecofin minutes, manifested in the form of a challenge by the Commission to have the Council decision annulled by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) on the grounds that the Council had not followed the rules and procedures as set out in the Treaty.

That action began on January 24, 2004, and the ECJ was asked to clarify the powers of each relating to the EDP. On July 13, 2004, the Court brought down its decision.

The upshot was that the Court made several determinations. First, it declared the Commission’s request that the suspension of action against France and Germany should be reversed inadmissible because a suspension.

Second, it annulled the Council decision in favour of France and Germany on the basis that it had used the wrong procedures.

The decision was a small victory for the Commission because the ruling clearly indicated that the EMU partners could not unilaterally ignore the rules that they had formally agreed to.

But the ‘law breakers’ got away with it because the impasse led to a renegotiation of the SGP and no sanction against France or Germany. A Pyrrhic victory nonetheless!

Conclusion

So we are back to this again but this time, Germany is the bully in a different guise – it is now the enforcer rather than the rebel. Hypocrasy has no limits it seems.

The history of the EMU to date has taught us that if Germany is unable to meet rules, then the rules will be altered. Otherwise, the rules will be used as a blunt weapon to devastate the employment base and living standards of weaker nations without the political clout of Germany.

The mindless Eurozone rules (German rules) have failed. It is time to move on and get over it.

It is time to abandon the project and release these nations and their people from the growth-sapping, poverty-inducing straitjacket.

Only a fool would support this sort of monetary arrangement. I am travelling to Italy in the coming month and hope to learn about the citizen revolt against this ideological vandalism.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

A minor point?

I don’t like the term ‘economic growth’ to describe an increase in income/output that comes about from a reduction in involuntary unemployment.

I think it is better to define economic growth as an increase in the underlying productive potential of an economy {determined by an economy’s factors of production and ‘technological progress’}.

Hence, in an economy with involuntary unemployment, it is possible, in the ‘short run’ to increase output and employment without any corresponding increase in the underlying productive potential {although the increase in economic activity will probably stimulate investment and increase productive potential}.

Since the neoclassical/neoliberal economists assume that the economy is ‘always’ at ‘full employment’ {no involuntary unemployment}, then, to them, the use of the term ‘growth’ to describe an increase in income/output is the same as an increase in the productive potential of an economy.

Using the latest data visualisation technology, I’ve put together a short clip that demonstrates Italy’s attempts to “turn the corner” using the tried-and-tested austerity technique. I hope I’ve pitched it at the right level of sophistication to help the European Commissioners understand the situation…

This is a total misreading of the situation in my book.

OK – Germany does not want to engage in a European Keynesian love festival.

Thats fine – I have no problem with this.

The great questions should be directed towards the elites based in the French , Italian and other nominal banking jurisdictions of Eurotrashland.

Why will they not assert a sort of psedo – Independence (i.e scale down their bank scarcity operations) that we can all pretend is Independence.

What are they afraid of ?

The European failing isn’t just economic. It is a political failing too, largely caused by a lack of democracy its its flawed structure. The former being a direct result of the latter

This is the late Tony Benn explaining it all very eloquently!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o0I-ZdvQz1o

Postkey, you are restricting your conception of economic growth to what could best be characterized as Ricardian unemployment and Marx’s initial position. But there is another aspect of economic growth which conforms to Marx’s later position and to Keynes’ position, unemployment as a consequence of lack of effective demand. Both sets of factors could lead to economic slowdowns in growth. There is, in addition, the problem of population decline. If a population is in decline, you don’t need as much growth as when it wasn’t. But that is a separate issue.

A Job Guarantee would eliminate involuntary unemployment to a substantial degree. This would render the neoclassical position otiose and show that their way of conceptualizing the issue fails to conform to the actual world in which we live.

While it is possible to increase economic activity by technological progress and related innovations, This would render the labor problem more difficult to solve, but not intractably so, I would have thought.