At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 84

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

Part III – Options for Europe

[THIS IS THE LAST SUBSTANTIVE CHAPTER – IT INTRODUCES THE APPROACH THAT THE EURO LEADERS HAVE TAKEN AND WHY A DRAMATIC CHANGE IN POLICY IS REQUIRED – IT LEADS INTO THE FINAL SEVERAL CHAPTERS WHICH DISCUSS THE SPECIFIC OPTIONS – WHICH YOU HAVE ALREADY READ. I WILL FINISH THIS CHAPTER BY THE END OF THE WEEKEND AND THEN NEXT WEEK WRITE THE INTRODUCTION AND START CHECKING]

Chapter 18 The European Groupthink – failing to take the correct path

The meltdown begins

Before the crisis had really hit Europe, the President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso was more concerned about calls for protection from China by the Member States than the growing financial turmoil in the world. In relation to concerns expressed about the instability in financial markets, Barroso told the Financial Times in March 2008, that “(w)e certainly have no intention at all of having some kind of European super-regulator … We think innovation in financial markets is good. Its been good for financial institutions, business and consumers … Of-course, we cannot be completely immune to the situation in America, but we think there is no rational reason to fear a recession in Europe” (Barber and Barber, 2008). He was early into his second five-year term as President. He was as wrong as one can be. The ‘sickly premature baby’, an epithet coined in 1998 by Gerhard Schröder for the euro, as he sought to build on the anti-European sentiment during the German Federal election of that year, had found early childhood very difficult (recall the German and French run-ins with the Excessive Deficit Procedure), and at the time Barroso was exuding his normal political confidence, all hell was about to break loose.

The US sub-prime mortgage market started to show signs of stress in late 2006 when data revealed a sharp increase in defaults. As 2007 unfolded, several of the key mortgage originators such as Countrywide started to report a rising incidence of late payments and overall delinquencies, particularly on loans where no equity was put up in advance by the borrowers, who often had poor credit ratings and little income. These mortgages were packaged up into complex financial products and on-sold to other investors, many of who had no capacity to judge the overall risk of the products they were purchasing. The world, which had been caught up in the deregulation, free market mania was now starting to know what fear of the unknown is all about.

On August 9, 2007, the poor state of the world’s financial system became more evident, when the large French bank, BNP Paribas (sixth-largest in Europe) froze the accounts of three of its hedge funds (Parvest Dynamic, Euribor and Eonia) worth some $US2.2 billion. The bank, with headquarters in London, said that it had lost the capacity to calculate the value of the funds because they were exposed to unknown risks in the US sub-prime market. In effect it had run out of cash because its assets were becoming untradeable in the financial markets. It was becoming obvious that increasing numbers of US mortgage holders were defaulting on their loans and this starting to impact on the core assets held by the major banks. Key markets which had been providing funds to banks dried up more or less instantly. Earlier in the same week, the US investment bank, Bear Stearns admitted that two of its mortgage hedge funds had collapsed. Within a day, several major investment funds in the US admitted losses and several of them had to issue statements assuring depositors that they had sufficient liquidity. The statements in many cases would prove false. The dominoes which had been lining up for some years under the cover of the Great Moderation hubris, were starting to fall.

The response of the US Federal Reserve provides an interesting expose of how the emerging crisis left the official regulators and officials flat-footed. Two days before BNP Paribas froze the accounts, the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve claimed that while there had been some volatility in the financial markets in recent weeks, which had led to tighter credit conditions, the economy “seems likely to continue to expand” and the “Committee’s predominant policy concern remains the risk that inflation will fail to moderate” (Federal Reserve, 2007a). Three days later, an updated statement was released saying that the Federal Reserve “is providing liquidity to facilitate the orderly functioning of financial markets” and that if depository institutions were struggling to get funds “the discount window” is always “available as a source of funding” (Federal Reserve, 2007b). On August 17, the Federal Reserve acknowledged that “(f)market conditions have deteriorated” and that the “he downside risks to growth have increased appreciably” (Federal Reserve, 2007c). At that stage, they cut the rate it provided funds at to the banks to restore orderly conditions in financial markets. We learned that central banks around the world had started to provide billions in various currencies to the private banks in an attempt to head of a ‘liquidity crisis’.

Typical of what had been happening in the lead-up, the Northern Rock Building Society in the UK exploited the deregulated and poorly supervised banking environment to grow far beyond its capacities through a series of takeovers of smaller building societies. The expansion strategy involved it borrowing heavily to fund its mortgage growth and then re-selling the assets in the international market for securatised assets. That market collapsed in 2007 and Northern Rock was thus unable to services its considerable stock of debt. On September 14, 2007, it had to seek emergency assistance from the Bank of England because it had run out of cash, but once this became public, its depositors demanded their cash back. It was the first bank run in the UK for 150 years. Early in 2008, the bank was nationalised, like so many other zombie financial institutions throughout the world. At any rate, the GFC had begun.

Despite the massive support to the banks coming from the central banks in each nation, the crisis worsened in 2008 as many more banks in the US and elsewhere started to collapse, the first large one being the Californian-based IndyMac Bank in July 2008. It has been a large sub-prime lender and could not find buyers for its failing assets. But events unfolded quickly in September and October 2008, when the crisis brought down many major financial institutions (for example, Lehman Brothers, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Washington Mutual, AIG, Wachovia, Citigroup, and Merrill Lynch). Some collapsed completely, others were sold in ‘fire sales’ to former competitors, and others were nationalised. The September 2008 turmoil in the money markets (massive withdrawals) effectively meant that firms were left unable to service maturing debts. The neo-liberal myth of self-regulating markets delivering efficiency and prosperity was being laid bare and the urgency for large-scale government intervention to prevent a complete financial meltdown and mass bankruptcies of both good and bad companies was becoming obvious. On October 3, 2008, the US government passed the ‘Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008’, which effectively saw the US Treasury committing to buy up around $US700 billion in failed mortgage-backed assets from investment banks and provide cash to the banks. On October 8, 2008, the British government announced that it had provided a bank bailout package equal to around £500 billion to support the banking system as the turmoil started to impact on the confidence of depositors.

The crisis quickly spread into the so-called ‘real’ economy as banks stopped lending, consumers stopped spending as their estimates of wealth, particularly their home equity, fell dramatically; firms stopped investing in new capital equipment as sales dried up; and major sectors, such as the construction industry nearly collapsed with large-scale employment losses. The government bailouts to that point had been concentrated on saving the banks and that what mattered most was maintaining sufficient spending to avoid recession and all the costs that came with that.

On November 3, 2008, the European Commission published it ‘Autumn economic forecast 2008-2010’, which predicted that “European Union economic growth should be 1.4% in 2008, half what it was in 2007, and drop even more sharply in 2009 to 0.2% before recovering gradually to 1.1% in 2010 (1.2%, 0.1% and 0.9%, respectively, for the euro area)” (European Commission, 2008: 1) and that “employment is set to increase only marginally in 2009-2010” and “unemployment is expected to rise by about 1 pp” (p.1). How wrong they were?

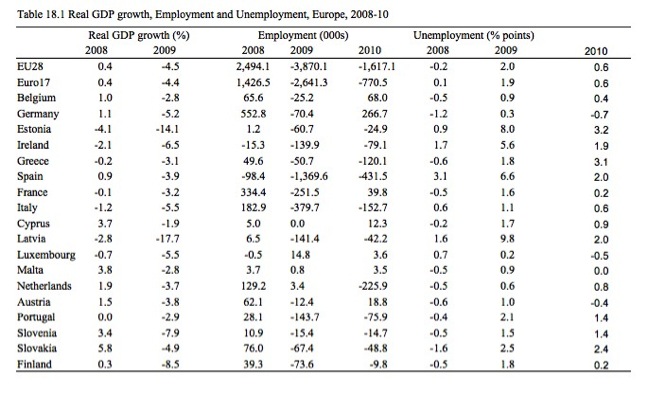

Table 18.1 shows the evolution of real GDP growth in 2008 and 2009, the change in employment (000s) and unemployment (points) over 2008, 2009 and 2010. The data shows in 2008, the slowdown in real GDP growth was substantially below the forecasts, but, worse was to come in 2009, when the EU economy overall shrank by 4.5 per cent and the euro-zone by 4.4 per cent. Further, far from a marginal increase in employment forecast for the years 2009 and 2010, employment fell substantially. Millions of jobs evaporated and unemployment rose by 2.5 times more than was predicted.

Source: Eurostat tables, GDP (nama_gdp_k), Employment (lfsi_emp_a) and Unemployment (une_rt_a).

[THIS CHAPTER WILL CONSIDER THE FISCAL COMPACT AND OTHER POLICY RESPONSES – IT DOES NOT INTEND TO BE A FULL HISTORY OF THE CRISIS IN EUROPE – JUST SET THE POLICY FAILURE IN THE CURRENT CONTEXT]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Barber, L. and Barber, T. (2008) ‘Barroso warns on protectionist pressures’, Financial Times, March 2, 2008. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/3ab2bf90-e8a1-11dc-913a-0000779fd2ac.html

European Commission (2008) ‘Autumn economic forecast 2008-2010’, IP/08/1617, Brussels, November 3, 2008. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-08-1617_en.pdf

Federal Reserve Bank (2007a) ‘Press Release’, August 7, 2007. http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20070807a.htm

Federal Reserve Bank (2007b) ‘Press Release’, August 10, 2007. http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20070810a.htm

Federal Reserve Bank (2007c) ‘Press Release’, August 17, 2007.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20070817b.htm

UNCTAD (2010) ‘Trade and Development Report, 2010, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, New York. http://unctad.org/en/Docs/tdr2010_en.pdf

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments