At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 74

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

Part III – Options for Europe

Chapter 22 Establishing a European fiscal capacity to save the Eurozone

[PRIOR MATERIAL HERE]

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

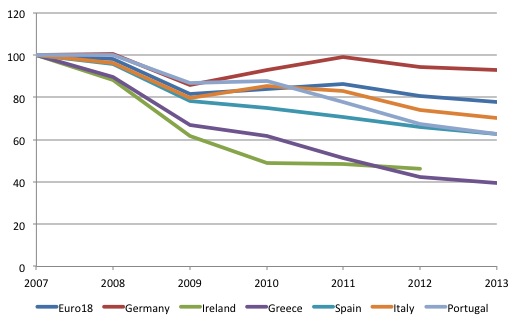

A rare proposal to stimulate aggregate demand

Varoufakis et al. (2013) recognise that creating a bank union and reducing the servicing costs of public debt in the Eurozone will not be sufficient to remedy the crisis. They clearly understand that there has been a dramatic slump in private investment in productive infrastructure in the Eurozone as a result of a loss of confidence and poor sales, which “threatens its living standards and its international competitiveness” (p.2). Further, the proposal is motivated by the observation that the monetary policy innovations are unable to revive the Southern European economies from depression. Their solution is to promote a large-scale, European-wide “Investment-led Recovery and Convergence Programme” (IRCP). It is one of the few proposals that explicitly seeks to reverse the austerity mindset by increasing total spending and, as a consequence, directly addresses the core short-run problem of stagnant growth. Figure 21.1 shows the extent of the investment collapse. By 2013, gross capital formation (investmen) in the Euro18 had fallen by 22 per cent relative to its 2007 level. For Germany the decline has been 6.9 per cent; Ireland 53.7 per cent (to 2012); Greece, a staggering 60.5 per cent; Italy 29.9 per cent; Spain 38.4 per cent; and Portugal 37.4 per cent. Adjustments of this magnitude are almost beyond belief and a testament to the total failure of the policy framework that the Eurozone leaders put in place to respond to the crisis.

Figure 21.1 Gross Capital Formation in the Eurozone, 2007-2013, 2007=100

Source: Eurostat, Annual National Accounts.

The IRCP proposal would divert borrowed funds raised by “bonds issued jointly by the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Investment Fund (EIF)” (p.6). The debt would not be counted against any Member State The authors note (p.6) that “the joint bonds can be serviced directly by the revenue streams of the EIB-EIF-funded investment projects”, although it is entirely unclear from the proposal what proportion of the funds would go to public infrastructure projects, which provide social returns as opposed to investment in private, profit-making ventures. It would be unfortunate if the value of the public investments was made on the basis of so-called ‘commercial returns’, which are inapplicable to the public sector aiming to deliver public service. The question then would be would the monetary returns on the remaining projects be sufficient to service and repay the debt. Further, in responding to the criticism that the debt could be expensive given the risk, the authors claim that there is a surplus of savings in the global markets that are “seeking sound investment outlets” (p.6). They merely assert that these projects would be desirable targets for such investment. The reality is that the investment climate is very uncertain at present because of the mass unemployment, falling incomes and cutbacks in public spending. The capacity of the projects to generate sufficient monetary profits to cover the borrowing costs, notwithstanding the likelihood that the EIB and EIF could access capital markets at lower rates, is debatable. An obvious question is if there are such substantial profitable investment opportunities available why haven’t the entrepreneurial class seen that? What sort of mypopia is operating to prevent the capitalists seizing on these opportunities?

This reality, which the authors admit “would be entirely within the central bank’s remit and charter” (p.13), once again raises the question as to whether this process would be better than the Member States determining their own spending priorities and kick-starting their own economies with similar secondary bond market assistance from the ECB. The retort is that the IRCP proposal would avoid any further rise in the debt levels of the Member States. But, again that is buying into the false claims that the debt levels are really the constraint on growth. With ECB support such as the OMT, the bond markets have no capacity to undermine the spending choices of the Member States. Of-course, then we get into the Excessive Deficit Mechanism debate, which the IRCP would avoid, and that is acknowledged. It is also clear that the ECB could play a part by purchasing the EIB-EIF bonds in the secondary market thus driving the cost of borrowing down to close to zero if it so wanted.

The argument that substantial new investment could kick-start growth if put into productive uses is sound. It mimics the emergency responses that marked the New Deal in the US between 1933 and 1937. The question is whether the scale of the program would be sufficient, given how large the output gaps are at present, to generate a recovery and whether a massive investment program could be absorbed without creating damaging imbalances. The authors merely assert that the scale of the program would be sufficient. If Germany is excluded, real GDP in 2013 for the remaining Eurozone nations was some 4 per cent below its 2007 level (some 253 billion Euros). Similarly, investment was about 27 per cent lower. Even assuming a very generous spending multiplier, the injection that would be required to make up that gap would dwarf the previous allocations that the EIB has handled.

Further, investment has a dual characteristic – it adds to demand in the current period and supply in the subsequent periods. Would the growth in consumption spending pick up quickly enough to absorb the new capacity? While the authors have characterised their proposal as akin to the New Deal (see Varoufakis, 2013), it should be remembered that the US program was heavily weighted towards providing relief to unemployed and impoverished citizens in the form of cash payments and direct public sector job creation. This sort of relief is outside of the ambit of the ‘Modest Proposal’ and thus it is questionable whether an investment-led answer to the deficient total spending will generate the gains necessary to lift household consumption in say Greece, where in 2013, it was around 25 per cent below its 2007 value.

Assessment

There is a plethora of schemes around that propose a way out of the Eurozone crisis. Some are more adventurous than others but most involve gymnastic manoeuvrings of debt classifications, dual currencies, or pension plans to work around the obvious problem that most refuse to recognise. Virtually all of the plans seek to work within the SGP straitjacket, appealing to political realities as the justification, without wanting to admit that the political realities are the part of the problem and until they change little will be done to progress the situation.

The debt manipulation schemes such as we have examined and others like the proposal for GDP-indexed bonds all assume there is something sacrosanct about the 60 per cent Maastricht threshold. The only relevance of the 60 per cent limit is that it is a reference value specified in the Treaty. It has no economic meaning or relevance. The Treaty has to be changed to move forward and in the meantime the sort of flexibility that was given to France and Germany in 2003 and 2004 via the Excessive Deficit Mechanism needs to become the norm. There is enough generality in the rules to stretch them very far as history has already demonstrated.

We did not consider the dual-currency proposals. They all fall foul of Gresham’s Law or the Copernicus Law, which tells you how long we have known that such schemes do not work. Yet they keep coming back. In the Eurozone context, they are proposed because there is a denial that the design of the monetary system is the problem. In effect, it is asserted that the problem is that nations lacking international competitiveness encounter rigidities that prevent them from cutting wages far enough. The dual-currency proposals – where the Euro (which denominates most contracts and trade transactions) operates in tandem with a local depreciated currency (in which wages are paid) – is just a ruse to cut real wages and assumes that the workers are blinded by what economists call ‘money illusion’, which is just a fancy term for assuming that workers are too stupid to know the purchasing power of their weekly wage and think they are better off than they actually are. Cutting wages will not help the Eurozone crisis unless it can be demonstrated that the policy will somehow increase consumption spending and reduce the propensity to save. The historical evidence tells us, repeatedly, that such strategies do exactly the opposite and make the spending shortage worse.

There is no doubt that a coordinated and large-scale investment strategy should be part of the revival of Europe that has been sabotaged by the neo-liberal austerity policies. But there has to be a recognition that no lasting recovery will come unless deficits overall rise and are held at elevated levels for an extended period.

The front line for progressives has to be an attack on the entire austerity culture. There has to be a concerted and coordinated challenge to the existence of the Eurozone rather than effort being put into a working out clever ways of working within the neo-liberal straitjacket. It is clear that Treaty change will be a drawn out process – everything in Europe is. It is also clear the depth of the crisis – the growing hunger among the poor; the crisis in the medical and health care systems; the rising youth unemployment and increasing social instability and growing political extremism – demands immediacy in the policy response. The next two chapters consider two proposals, one of which would retain the Euro but dramatically restructure the monetary system, while the other would abandon the union and restore currency sovereignty to the individual nations and allow their democratically elected governments to work in the interests of their citizens without falling prey to the dictates of unelected cabals in Brussels, Frankfurt or Washington.

[TO BE CONTINUED – CONCLUDING REMARKS FOR THIS OPTION WILL COME TOMORROW]

Chapter 23 Abandon the Euro – the costs, threats and opportunities

European politics and policy making is caught in two very powerful and destructive Groupthink vices at present. The first, is the age-old ‘Rivalité franco-allemande’ or if you are on the other side of the border the ‘Deutsch-französische Erbfeindschaft”. A corollary to this rivalry is a disdain for the Latins who by geographic proximity cannot be ignored, much to the angst of those further North. The second, is the domination of free market economics, which though virtually deficient of any empirical validity and riddled with internal theoretical inconsistencies, still rules the academy and through its graduates, the policy making sphere. How the economics profession has been able to convince the rest of us that by ‘counting angels on a pinhead’ and then not being able to correctly add up those that they claim to see (their so-called ‘economic models’), could possibly represent a viable framework for enhancing societal well-being is a study in itself and constitutes one of the biggest frauds of the C20th and beyond. Indeed, there is very little ‘society’ in the mainstream economics, which thinks of us as being ultra rational, with massive computers for brains (able to see into the future with perfect vision), and only concerned about ourselves as individuals. Aggregations of individuals in their models make no sense at all. All the evidence from psychology and behavioural studies, that is, from experts who actually bother to study human behaviour rather than adopt abstract models of it while sitting behind a desk somewhere, tell us that the assumptions about human motivation and decision-making that are essential for the mainstream ‘economic models’ to work are nonsensical.

Neither vice will release its destructive grip on European affairs easily, and the cultural and historical aspects of the first are probably permanent constraints on progress. When the Gauls and the Germans began hating each other is a matter of history – but it was a long time ago. Historians create all sorts of revisions to suit their own angle, but it is clear that the two ‘nations’ were at odds after Napolean incorporated German-speaking areas such as the Rhineland into the First Republic. His disdainful treatment of the German aristocracy, including the various German-speaking monarchs spawned German nationalism and led to the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. German unification was motivated, in part, by a desire for a German-speaking power to rival that the geo-spatial domination of France (see Wetzel, 2001). It is true that this ‘enmity’ has evolved in the Post World War II period and the diplomacy is less chauvinistic and the prospect of martial expression is minimal. Some have even considered the relationship between the two great European nations to be one of ‘Amitié franco-allemande’. But, always simmering is the clash of culture and the legacy of World War II. While the rivalry was intense and open under President de Gaulle, which held back Europan integration, later, the rivalry was expressed from the French side as a desire to neutralise German power – and the only way to do that was to create a European state where France hoped to dominate. From the German-side, whether anyone wants to talk about it or not, as a result of their actions during the 1930s and 1940s, a deep and silent shame gripped the nation. Their only source of national pride became their economic acumen – their technical and organisation skills and the discipline of their workers. They wanted the ugly German to become the clever German. European integration became a way the German nation could win back some respect by demonstrating that it could be part of a peaceful Europe and bring its engineering acumen to benefit all. Reunification accelerated that desire given how paranoid the rest of Europe, particularly France became when West and East were to become a united Germany. But, while Mitterand and Schmidt seemed to be working together, the motivations were quite different.

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Arghyrou, M. and Tsoukalas, J. (2010a) ‘The Option of Last Resort: A Two-Currency EMU’, EconoMonitor, February 7, 2010· http://www.economonitor.com/blog/2010/02/the-option-of-last-resort-a-two-currency-emu/

Arghyrou, M. and Tsoukalas, J. (2010b) ‘The Option of Last Resort: A Two-Currency EMU’, Cardiff Business School Working Paper E2010/14, November 2010. http://business.cardiff.ac.uk/sites/default/files/E2010_14.pdf

Borensztein, E. and Mauro, P. (2002) ‘Reviving the case for GDP-indexed bonds’, IMF Policy Discussion Paper, 02/10, September 2002. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/pdp/2002/pdp10.pdf

Buiter, W. (2008) ‘Can Central Banks Go Broke?’, Policy Insight, No. 24, Centre of Economic Policy Research, May. http://www.cepr.org/sites/default/files/policy_insights/PolicyInsight24.pdf

Bundesverfassungsgericht (2014) ‘Entscheidungen: über die Verfassungsbeschwerde … gegen 1 den Beschluss des Rates der Europäischen Zentralbank vom 6. September 2012 betreffend Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) und die fortgesetzten Ankäufe von Staatsanleihen auf der Basis dieses Beschlusses und des vorangegangenen Programms für die Wertpapiermärkte (Securities Markets Programme – SMP), BvR 2728/13, February 7, 2014. http://www.bverfg.de/entscheidungen/rs20140114_2bvr272813.html

Delpla, J. and von Weizsäcker, J. (2010) ‘The Blue Bond Proposal’, bruegel policy brief, Issue 2010/03, May 6, 2010. http://www.bruegel.org/download/parent/403-the-blue-bond-proposal/file/885-the-blue-bond-proposal-english/

De Grauwe, P. and Yuemei Ji, Y. (2013) ‘Panic-driven austerity in the Eurozone and its implications’, Voxeu, February 21, 2013. http://www.voxeu.org/article/panic-driven-austerity-eurozone-and-its-implications

De Grauwe, P. (2013) ‘Debt Without Drowning’, May 9, 2013. http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-debt-pooling-scheme-that-the-eurozone-needs-by-paul-de-grauwe

Goodhart, C. and Tsomocos, D. (2010) ‘The Californian solution for the Club Med’, Financial Times, January 24, 2010. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/5ef30d32-0925-11df-ba88-00144feabdc0.html#axzz308OAO0YZ

ECB (2012) ‘Technical features of Outright Monetary Transactions’, Press Release, September 6, 2012. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2012/html/pr120906_1.en.html

Enderlein, H., Bofinger, P., Boone, L., de Grauwe, P., Piris, J-C., Pisani-Ferry, J., Rodrigues, M.J., Sapir, A. and Vitorino, A (2012) ‘Completing the Euro. A road map towards fiscal union in Europe’, Notre Europe. http://www.notre-europe.eu/media/pdf.php?file=completingtheeuroreportpadoa-schioppagroupnejune2012.pdf

Issing, O. (2009) ‘Why a Common Eurozone Bond Isn’t Such a Good Idea’, White Paper No. III, Centre for Financial Studies, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, July.

Soros, G. (2013) ‘How to save the EU from the euro crisis’, UK Guardian, April 10, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/apr/09/george-soros-save-eu-from-euro-crisis-speech

Varoufakis, Y. and Holland, S. (2011) ‘A Modest Proposal for Resolving the Eurozone Crisis’, Policy Note 2011/3, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, 2011. http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/pn_11_03.pdf

Varoufakis, Y., Holland, S. and Galbraith, J.K. (2013) ‘A Modest Proposal for Resolving the Eurozone Crisis, Version 4.0’, July 2013. http://varoufakis.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/a-modest-proposal-for-resolving-the-eurozone-crisis-version-4-0-final1.pdf

Müller, M. (2013) ‘EU Unemployment Insurance: Getting the Eurozone back on track’, thenewfederalist.eu. July 5, 2013. http://www.thenewfederalist.eu/EU-Unemployment-Insurance-Getting-the-Eurozone-back-on-track,05865

Jauer, J., Liebig, T., Martin, J.P. and Puhani, P. (2014) ‘Migration as an adjustment mechanism in the crisis? A comparison of Europe and the United States’, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, January. http://www.oecd.org/migration/mig/Adjustment-mechanism.pdf

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill fails to see that there is nothing much underneath the Euro extreme value added entrepot.

Very little Primary & basic secondary industry remains- indeed what remains services the needs and wants of the financial capitals.

Walk through any typical French market town – NOTHING HAPPENS IN THESE PLACES AND HAS NOT HAPPENED FOR A VERY LONG TIME.

Traffic moves on to another non place as people use & need cars to search for scarce money.

The remaining people who live in these towns live off of declining pensions and the like.

Why do you need to overproduce more capital goods in such a strange scarce ecosystem.

Its much like a Polar Ocean infact.

The food base is essentially highly productive Krill.

Nothing much in between.

And giant Whales (corporate / banking bodies) eating most of the biomass.

A extremely efficient but highly unstable ecosystem prone to never ending collpase and expansion episodes.