At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 58

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

Chapter X The Stability and Growth Pact – neither growth nor stability

[CONTINUING THIS SECTION]

As another example of the flawed analysis that was used to justify the fiscal rules in the SGP, the OECD published a paper in their Economic Studies series in 2000, which aimed to explore the scope that the Maastricht Treaty provided EMU governments to respond to a drop in total spending in their economy which would reduce economic growth relative to the potential output levels, if there was full employment (Dalsgaard and de Serres, 2000). The authors claimed in relation to the SGP that the “imposition of such debt and deficit ceilings does not necessarily impose a binding constraint on the use of counter-cyclical fiscal policy because countries can run a structural deficit that is well below 3 per cent of GDP” (p. 116). They recognise that this claim is contingent on assumptions being made about the size of likely spending shocks.

Of-course, consistent with the OECD’s mission to publish ‘research’ that supports their neo-liberal agenda, the paper’s findings “validate the ‘close-to-balance’ rule stipulated by the Stability and Growth Pact” (p. 117). The problem with the analysis is that they based their analysis on estimates of output gaps – the difference between actual output and hypothesised potential output – which are biased downwards, as explained previously.

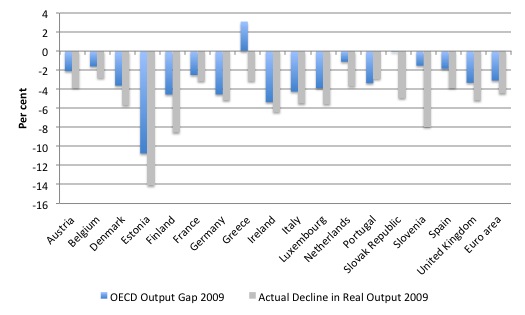

Figure X.1 shows the estimates of the output gap provided by the OECD for some selected European nations and the actual percentage decline in real GDP (actual output) for 2009. In every case (other than Portugal) the decline in actual output in the first year of the crisis exceeded the OECD measure of the output gap. Even if we assumed that in 2008, at the onset of the crisis, all the economies were producing at full capacity (so real output was equal to potential and the output gap was zero) the actual decline in real production would imply larger output gaps than those published by the OECD. A moment’s reflection on the estimate for Greece alerts one to the problem of the OECD estimates. They estimated that Greece was actually producing at around 103 per cent of their capacity in 2008, which is unlikely given that the unemployment rate was still very high at 7.8 per cent.

Figure X.1 OECD output gap estimates and actual decline in real GDP, 2009

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2013 Issue 2, Statistical Annex Table 10. Eurostat National Accounts database.

Note: the output gap measure is the deviation of actual from estimated potential as a percent of the estimated potential whereas the actual decline in real GDP is the percentage change in real GDP between 2008 and 2009.

A possible retort is that the estimate of potential output fell in 2009 as actual output fell, which would explain why the estimated output gap was less than the actual decline in real output. Economists use a concept called ‘hysteresis’ to capture this possibility. One plausible story about this effect might be that as actual output falls and the economy moves into recession, firms stop investing in new productive capacity and scrap unused capacity, which reduces the potential productive capacity of the economy. While that narrative has strong empirical support, it takes a prolonged downturn before the pessimism of firms leads them to scrap their existing machinery and equipment. The response in the first year of a crisis would be more typically to turn of machines and leave other capacity idle while they ascertained the depth and likely duration of the downturn. In that case, it is highly unlikely that potential output fell sharply in 2009 in these nations.

Further, given that the economies started the downturn with persistently high unemployment rates in most cases, the likely widening of the output gaps in 2009 was probably even larger than the actual decline in real output. This also means that a component of the actual fiscal deficit for each country in 2008 was certainly ‘cyclical’, capturing the deviation from full capacity.

As explained previously, the underestimate of the output gaps matters when the task turns to estimating how much of the rise in the actual fiscal deficit can be explained by the downturn in the economy (the automatic stabiliser impact). The European Commission and bodies like the OECD continually argued that, given historical output gaps during recessions and estimates of the sensitivity of the automatic stabilisers to changes in output gaps, the shifts in fiscal deficits due to the crisis alone would still be within the 3 per cent limit.

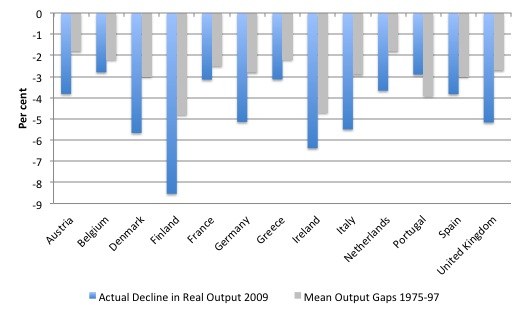

Figure X.2 shows the average output gaps during recessions between 1975-97 calculated by Dalsgaard and de Serres (2000) and the actual decline in real GDP in 2009 for a range of European nations. It is clear that the decline in actual output in 2009 exceeded the average output gaps during recessions between 1975-97, which were used to justify the SGP restrictions, by a considerable margin in all cases except Portugal. This suggests that the SGP was designed on excessively optimistic assumptions about the likely magnitudes of recessions in Europe. The experience of the pre-Euro period is also not a sound benchmark because the nations concerned enjoyed the fiscal latitude that comes with being the issuer of ones’ own currency. This latitude almost assuredly allowed output gaps to be lower than otherwise as nations sought to stimulate their economies in the face of a private spending decline to ensure unemployment didn’t rise to politically unacceptable levels.

Figure X.2 Average output gaps during recessions between 1975-97 and actual decline in real GDP 2009

Source: Dalsgaard and de Serres (2000) for historical estimates of output gaps, Eurostat National Accounts database for actual real GDP data. The nations shown are limited by the historical data provided in Dalsgaard and de Serres (2000).

The SGP and the bond markets

The SGP also increases the vulnerability of national governments to the private bond markets. Prior to the 1990s, governments and central banks worked together to ensure that the fiscal plans of the government would always have sufficient funds, even though, as we will discuss in a later chapter, the governments unnecessarily continued to issue debt to the private bond markets to match their deficits. The reference to the lack of necessity in this case refers to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system which freed currency-issuing governments from the need to issue any debt at all. The convention of issuing debt was continued because the dominant conservatism among economists saw it as a means of pressuring governments to run smaller deficits than might be required. Shifts in public debt ratios are always a sensitive issue in the public arena, even though most of the financial commentators and the public in general do not understand the meaning or relevance of the data that is paraded on financial reports and the like on a daily basis as if it is important.

During this period, central banks in many European nations regularly purchased government debt directly from the treasuries if they felt accessing private funds in the bond markets would not be in the interests of the government. This practice was outlawed under the Maastricht Treaty. The upshot was that once the Eurozone came into operation, all Member States had to seek loans from the private bond markets to cover any fiscal deficits. The bond markets thus were elevated in importance and within the Eurozone began to dictate the cost of public borrowing and had the capacity to withdraw funds altogether and force a Eurozone nation into insolvency.

While most financial commentators regularly discuss Greece or France in the same breath as the United Kingdom or even the United States when considering bond market responses and the like, the fact is that the EMU nations are hamstrung as a consequence of ceding their monetary policy authority to the ECB and abandoning their independent exchange rate and the capacity to run an independent fiscal policy.

For nations that issue their own currency, the bond markets are impotent and know that the corresponding central bank can always set the terms (interest rates) that public debt is issued. Governments in these cases only have to pay what the bond markets demand if the governments concedes to the false authority of the markets. Otherwise, the government is fully in charge of the bond issuance process and the markets become compliant recipients of corporate welfare in the form of a guaranteed (risk-free) annuity (with interest) in exchange for non-interest bearing bank reserves. The bond markets know that there is no default risk on bonds that are issued in the currency that the central bank creates.

The EMU nations, however, do face insolvency risk and the bond markets clearly understand that. In the absence of any ECB support, these nations are reliant on the terms set by the bond markets for any debt they issue. The excessive deficit procedure built into the SGP acts as an alarm bell for the bond markets because it unnecessarily invokes a sense of crisis when the real crisis is the loss of employment and output and the responsible response is to support total spending with larger deficits, which almost certainly exceed the SGP threshold. In creating this sense of crisis, the solvency risk of the nations is highlighted. By forcing all the fiscal adjustment onto the Member States and then restricting their capacity to meet an economic crisis, the EMU ensures that recessions will be deeper than they should be and that peripheral crises, such as the refusal of bond markets to lend to governments at reasonable rates, will become more likely.

Assessment of SGP

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was designed to place binding constraints on the capacity of national governments to use their spending and taxation capacities to fulfill their legitimate responsibilities. The constraints effectively limit the capacity of these governments to respond to crises and the result has been that millions of workers in Europe have unnecessarily lost their jobs as the Troika has bullied governments into adopting ‘pro-cyclical’ policy changes, which are the anathema of sound fiscal practice.

It is now widely recognised that the fiscal rules that are central to the SGP are highly arbitrary without any solid theoretical foundation or internal consistency (see Mitchell, Muysken and Van Veen, 2006). The rationale of controlling government debt and budget deficits were consistent with the rising neo-liberal orthodoxy that promoted inflation control as the macroeconomic policy priority and asserted the primacy of monetary policy (a narrow conception notwithstanding) over fiscal policy. Fiscal policy was forced by this inflation first ideology to become a passive actor on the macroeconomic stage.

As a result of the establishment of the European Central Bank (ECB), European member states now share a common monetary stance. The SGP was the instigation of Germany, which wanted fiscal constraints put on countries like Italy and Spain because they suspected these nations would adopt reckless government spending policies, which would undermine price stability. The SGP was straitjacket which aided the transfer of the Bundesbank culture into the wider Europe (see Mitchell et al., 2006; Mitchell and Muysken, 2008).

The fiscal rules formalised in the SGP were criticised by many economists at the time of inception. Even relatively conservative economists such as De Grauwe (2003) argued that there is no rationale for zero government debt, which a zero deficit would imply in the long run (see also Fitoussi and Saraceno, 2004). The argument, which was rejected by the increasingly dominant Monetarist fringe within the mainstream economics profession, was that public borrowing should be used to finance capital expenditures. Since government invests a lot in infrastructure and other public works, which allow the private sector to grow more quickly, those investments should at least allow for a fiscal deficit. This was already recognised by the classical economists as a ‘golden rule of public finance’ (see Buiter and Grafe, 2004). So even within an orthodox public finance model, the stipulations of the SGP were difficult to justify.

In a later chapter we will develop a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) framework, which demonstrates that economists who advocate the SGP fail to comprehend the basis of government spending and in imposing these voluntary financial constraints on government activity, deny essential government services and the opportunity for full employment to their citizenry.

We will learn that the requirement that fiscal deficits should be zero on average and never exceed 3 per cent of GDP not only restricts the fiscal powers that governments would ordinarily enjoy as a result of issuing their own currencies (so-called ‘fiat currency regimes’), but also violates an understanding of the way fiscal outcomes are effectively determined by the private spending decisions rather than exclusively by what the government does. Any economist with even the simplest understanding of the way in which automatic stabilisers operate will see the lack of wisdom in the SGP rule. A sharp negative demand shock which causes an economic downturn will reduce tax receipts and increase benefits, automatically increasing the deficit. Reducing government expenditures in that situation to meet the rule will worsen (prolong) the recession, which is then likely to involve the country in further SGP rule violations and bond market problems. The vicious circle of spending cuts implied is unsustainable and amounts to fiscal vandalism. In other words, fiscal policy becomes ‘pro-cyclical’ under the SGP rule violating any sensible ambitions that are the ambit of responsible fiscal management. This is the major reason that France and Germany have refused to comply with the 3 per cent rule in the early years of the EMU, a topic we return to in a later chapter.

Another problem relates to the bias in the way fiscal adjustment is conceived. In particular, it is automatically assumed that discretionary actions to reduce the budget deficit will involve spending cuts rather than increasing taxes. This gives the impression that some politicians are not primarily concerned about the size of the budget deficit, but covet the 3 per cent rule as a welcome excuse to force their ideological predilection for small government. In other words, the ideological bias against public activity, particularly in the social security sphere, is dressed up as prudential economic management to give the crude religious zeal an air of authority and respectability.

The SGP rule cannot be seen in isolation of the acceptance by EU countries of the voluntary monetary policy straitjacket that the ECB acceptance imposes. While the ECB now has a monetary policy monopoly across the EU countries, it is not politically responsible for its actions. The EU countries have voluntarily allowed the ECB to be an unelected and independent body whose sole aim is to control inflation. The fundamental democratic principle that the citizens have the ability to cast judgement on the policies of their representatives at regular intervals has been abandoned in this setup. Former World Bank adviser, Joseph Stiglitz (2002: 45) has criticised this aspect of the EU model

There is a wide-spread feeling that Europe’s independent Central Bank exacerbated Europe’s economic slowdown in 2001, as, like a child, it responded peevishly to the natural political concerns over growing unemployment. Just to show that it was independent, it refused to allow the interest rates to fall, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. The problems partly arose because the European Central Bank has a mandate to focus on inflation, a policy … that can stifle growth or exacerbate an economic down turn.

This voluntary monetary policy straitjacket suggests that countries have to use fiscal policy to react to economic shocks which affect the real economy. However, the SGP has imposed an inflexibility on this discretion and stagnant economic outcomes have been the norm (see Bofinger, 2003; Buiter, 2006).

It is often said that the European economies are sclerotic, which is usually taken to mean that their labour markets are overly protected and their welfare systems are overly generous. However, the real European sclerosis is found in the inflexible macroeconomic policy regime that the Euro countries chose to contrive. The rigid monetary arrangements conducted by the undemocratic ECB and the irrational fiscal constraints that are required if the SGP is to be adhered to, render the nation states within the Eurozone incapable of achieving low levels of unemployment and increasing income growth.

The SGP promotes neither stability or growth.

Chapter X The convergence farce – smokescreens, accounting tricks, and denial

[NEXT – THE CONVERGENCE FARCE]

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Andrews, E.L. (1997) ‘German’s Slick Bookkeeping to Meet Euro Goal Is Scrapped’, New York Times, June 4, 1997. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/06/04/world/germans-slick-bookkeeping-to-meet-euro-goal-is-scrapped.html

Bofinger, P. (2003) ‘The Stability and Growth Pact neglects the policy mix between fiscal and monetary policy’, Intereconomics, 38(1), 1-7.

Böll, S., Reiermann, C., Sauga, M. and Wiegrefe, K. (2012) ‘Operation Self-Deceit: New Documents Shine Light on Euro Birth Defects’, Der Spiegel, May 8, 2012. http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/euro-struggles-can-be-traced-to-origins-of-common-currency-a-831842.html

Buiter, W.H. (2006) ‘The “Sense and Nonsense of Maastricht” Revisited: What Have we Learnt about Stabilization in EMU?’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(4), 687-710.

Buiter, W. (2009) ‘The unfortunate uselessness of most ‘state of the art’ academic monetary economics’, Financial Times, March 3, 2009. http://blogs.ft.com/maverecon/2009/03/the-unfortunate-uselessness-of-most-state-of-the-art-academic-monetary-economics/

Buiter, W.H. and Grafe, C. (2004) ‘Patching up the pact; Suggestions for enhancing fiscal sustainability and macroeconomic stability in an enlarged European Union’, Economics of Transition, 12(1), 67-102.

Buti, M., Franco, D., and Ongena, H. (1997) ‘Budgetary Policies during Recessions – Retrospective Application of the “Stability and Growth Pact” to the Post-War Period’, Economic Papers, 121, 1-33. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication11240_en.pdf

Dalsgaard, T. and de Serres, A. (2000) ‘Estimating Prudent Budgetary Margins for EU Countries: A simulated SVAR model approach’, OECD Economic Studies, 30, 115-147. http://www.oecd.org/tax/public-finance/2732422.pdf

De Grauwe, P. (2003) The Stability and Growth Pact in need of reform, CEPS.

Deutsche Bundesbank (1998) ‘Stellungnahme des Zentralbankrates zur Konvergenzlage in der Europäischen Union im Hinblick auf die dritte Stufe der Wirtschafts- und Währungsunion’, April 1998. http://www.bundesbank.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/Veroeffentlichungen/Monatsberichtsaufsaetze/1998/1998_04_konvergenzlage.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

Dunbar, N. and Martinuzzi, E. (2012) ‘Goldman Secret Greece Loan Shows Two Sinners as Client Unravels’, Bloomberg News, March 6, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-06/goldman-secret-greece-loan-shows-two-sinners-as-client-unravels.html

Eichengreen, B.J. (1997) ‘Saving Europe’s automatic stabilisers’, National Institute Economic Review, 159(1), 92-98.

Eichengreen, B.J. and Wyplosz, C. (1998) ‘The stability pact: more than a minor nuisance?’, Economic Policy, 26. 65-114.

European Central Bank (1998) ‘Joint communiqué on the determination of the irrevocable conversion rates for the euro’, May 2, 1998. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/1998/html/pr980502.en.html

European Monetary Institute (1998) ‘Convergence Report’, March 1998. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/conrep/cr1998en.pdf

EurActiv (2010) Theo Waigel: Greek crisis exposed EU weaknesses’, September 13, 2010. http://www.euractiv.com/euro/waigel-stability-pact-not-flawed-all-countries-must-play-rules-news-497698

European Council (1997a) ‘Presidency Conclusions’, Amsterdam, June 16-17, 1997.

http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/032a0006.htm

European Council (1997b) ‘Resolution of the European Council on the Stability and Growth Pact Amsterdam, 17 June 1997’, Official Journal C 236, 02/08/1997 P. 0001 – 0002. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31997Y0802%2801%29:EN:HTML

European Council (1998) ‘Presidency Conclusions’, Vienna, December 11-12, 1998. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/00300-R1.EN8.htm

European Monetary Institute (1998) ‘Convergence Report’, March 1998. http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/conrep/cr1998en.pdf

Fitoussi, J.P. and Saraceno, F. (2004) ‘The Brussels-Frankfurt-Washington Consensus: Old and new tradeoffs in economics’, Document de Travail 2004-02, Observatoire Français des Conjunctures Economiques: Paris.

Italianer, A. and Pisani-Ferry, J. (1992) ‘Systèmes budgétaires et amortissement des chocs régionaux : implications pour l’union économique et monétaire’, Economie prospective internationale, 51, 49-69. http://www.cepii.fr/IE/PDF/EI_51-4.pdf

Mitchell, W.F., Muysken, J. and Van Veen, T. (2006) Growth and Cohesion in the European Union, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pisani-Ferry, J., Italianer, A. and Lescure, R. (1993) ‘Stabilizatoin properties of budgetary systems: A simmulation approach’, in The Economics of Community Public Finance, European Economy, Reports and Studies, 5.

Pisani-Ferry, J., Vihriälä, E. and Wolff, G. (2012) ‘Options for a Euro-Area Fiscal Capacity’, Bruegel Policy Contribution, Issue 2013/01, January. http://www.bruegel.org/download/parent/765-options-for-a-euro-area-fiscal-capacity/file/1636-options-for-a-euro-area-fiscal-capacity/

Stiglitz, J.E. (2002) Globalization and its discontents, London, Penguin Group.

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

this comment is astounding

“There is a wide-spread feeling that Europe’s independent Central Bank exacerbated Europe’s economic slowdown in 2001, as, like a child, it responded peevishly to the natural political concerns over growing unemployment. Just to show that it was independent, it refused to allow the interest rates to fall, and there was nothing anyone could do about it. The problems partly arose because the European Central Bank has a mandate to focus on inflation, a policy … that can stifle growth or exacerbate an economic down turn.”

Now THAT point (not to mention all the others that continue in a sclerotic macro-economic regime) defines a lack of leadership. If the PM of not one country was willing to put his/her foot down & draw a line in the sand …. then why didn’t they just resign?

Ya don’t just stand back and watch your people bleed just because they’ve painted themselves into a purely nominal corner. What happened to empathy and responsibility, and basic morality?

Surely I’m not the only one who, after following this illuminating review, keeps thinking that another Nuremberg trial is called for? The dimensions of the distributed impact on the citizens of Europe is unprecedented, even compared to all their past wars. It’s criminal, and they’re doing it to themselves.

“Why” is the only question. Every step of the way.

Bill’s laid out a ton of relevant data. However since data is meaningless without context, the implication is that available, known data was meaningless to context, at the time each decision in this long string was taken.

So the real question is why on Earth such a long string of policy “leaders” was so behind on context that they misused available data to this extent? Any why on Earth were so many, supposedly well educated, electorates allowing their leaders to operate in such a unprepared manner? That is the definition of danger.

You don’t send a disoriented representative to a casino, entrusted with your entire families future options! You might well end up as a serf.