At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 48

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

The Ratification debacle – 1992-93

[FINISHING OFF THIS SECTION …]

The ratification process, was the first ‘dipping of the toes’ into the mirky EMU waters and, despite the confident hubris from the politicians and their apparatchiks, it turned out to be, in the words of Szász (1999: 170) “a painful and protracted process, causing considerable embarrassment to many governments. Strong opposition manifested itself not only in countries where the governments had been more or less pushed along, like Britain and Denmark, but also in those where the governments had taken the lead, France and Germany”. In 1992 it was clear that the populations of the prospective EMU partners were less than enamoured with the idea.

It is also clear that the sense of denial that had formed among the political classes had created a dislocation from reality. The European Commission put out a brochure in May 1991 – ‘Economic and Monetary Union: Europe on the Move’ – which was a political exercise aimed at convincing the public that things were heading in a direction that would benefit all (European Commission, 1991). It was glossy and expensive to produce but failed to grasp any of the realities that would be realised once the full EMU plan was implemented and confronted with a serious economic downturn, such as that imported from the US sub-prime collapse in 2007.

Szász (1999: 171) provided a stark account of how the political authorities “themselves were unclear … and lacked an overall view”. He recounted a meeting he attended in May 1990 in his role as the former Executive Director of the Dutch central bank with members of the “Dutch cabinet most involved in European issues” (p.171). The Dutch were fervent advocates of “European integration in general and of EMU in particular” (p. 171). He noted that when he was listening to the discussion he formed the view that “the ministers were looking at the implications of EMU seriously for the first time, and did not at all like what they saw” (p.171). The Dutch Prime Minister evidently in the summing up “wondered whether the political authorities realised what they were doing” (p. 171). Wim Kok, the Finance minister, reminded the gathering that it was 1990 and the discussions about the EMU “had been going on for quite some time” (p.171).

The ratification process did not generate the positive reinforcement of what the politicians had been up to since the Delors Plan was released in 1989. There was uncertainty, dissent and, in retrospect, a sense of foreboding of what was to come.

And then along came Black September, which was partially caused by the negativity in the public arena that manifested during the flawed ratification process.

Black September 1992

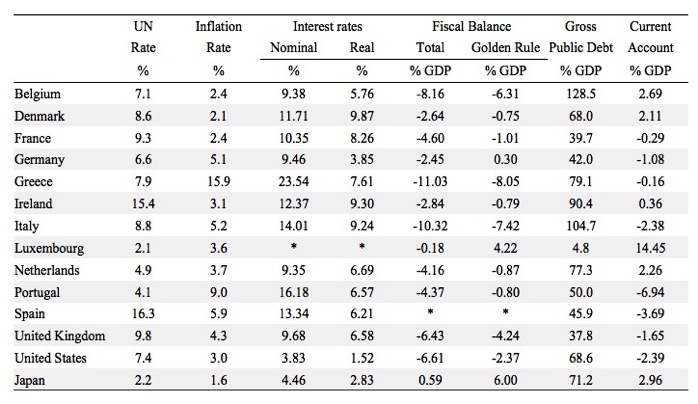

Once the ratification process was completed, attention turned to meeting the convergence criteria. Table 2 provides a snapshot of where the nations were in terms of the major convergence criteria in 1992. The unemployment rate, which was ignored in articulating what a desirable convergence should look like, is also shown. To put a finer point on it, the policy makers considered the unemployment rate (via its link to the economic growth rate) to be the ‘adjustment variable’ as they pursued policies designed to meet the demands of the convergence criteria. They knew that to reduce public debt ratios and fiscal deficits and bring inflation rates into line they would have to reduce domestic activity, given that their undertakings under the EMS in terms of maintaining the narrow exchange rate bands gave them no other source of adjustment. The logic of forcing the heavy adjustment work onto the domestic economy rather than the exchange rate was obvious – unemployment rates would have to rise for nations such as Belgium, Ireland, Greece, Italy, Portugal and the United Kingdom. And so they did. Belgium’s unemployment rate rose from 7.1 per cent in 1992 to 9.7 per cent in 1995; Greece from 7.9 to 9.2 per cent; Spain from 16.3 per cent to 20 per cent; France from 9.3 to 10.6 per cent; Italy from 8.8 to 11.2 per cent; the Netherlands from 4.9 to 7.1 per cent’ Portugal from 4.1 to 7.2 per cent as policy makers pushed their economies into an effort to meet the criteria.

With the large disparities across the 12 Member States in terms of the convergence criteria variables it was unimaginable that all the components of the convergence agreement could be met. For example, to maintain the exchange rates within the narrow tolerances agreed, some nations would have to increase interest rates, which would violate the undertakings with respect to maintaining narrow interest rate differentials to bring given the scale of the adjustments required.

Exchange rate adjustment was staring the policy makers and politicians in the face but they blithely chose to ignore it. Until September 1992 – that is.

Table 2 Convergence Criteria data, 1992

Source: AMECO database.

[NEXT WE EXAMINE BLACK SEPTEMBER WHERE IT ALL LOOKED LIKE IT WOULD COME UNSTUCK – I DIDN’T HAVE MUCH TIME TODAY AS THE THIRD WEEK IN MARCH IS WHEN THE MAJOR COMPETITIVE RESEARCH FUNDING APPLICATIONS IN AUSTRALIA HAVE TO BE FINALISED AND SUBMITTED – TODAY WAS THE DAY AND WE WERE VERY BUSY – MUCH MORE WILL BE FORTHCOMING TOMORROW]

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

European Community (1990) ‘European Parliament, Rapid Information Note, SP (91) 2669, 21-25 October 1991 Plenary Session’, October 25, 1991. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/emu_history/documentation/chapter13/19911025en07epdebateonemu.pdf

European Council (1992) ‘Conclusions of the Presidency’, December 11-12, 1992.http://www.european-council.europa.eu/media/854346/1992_december_-_edinburgh__eng_.pdf

German Constitutional Court (1993) ‘Judgment of 12 October 1993 – 2BvR 2134/92 and 2 BvR 2159/92’, Decisions of the Bundesverfassungsgericht, Vol. 89, Page 155.

Kinzer, S. (1991b) ‘Kohl Calls the Path to European Unity Irreversible’, New York Times, December 14, 1991

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments