At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 49

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

The Summer of ’92 aka Black September 1992 aka Black Wednesday 1992

While the ‘Summer of 42’ was a comedy-drama with European connections, the Summer of 1992 in Europe was anything but comedic and threatened to stop the transition to the EMU before it had really started. But like the current crisis in the Eurozone, the politicians and European Commission bureaucrats managed to construct the near meltdown of the EMS as a demonstration of why a single currency was needed rather than a reason to abandon their half-baked plan. Any reasonable interpretation, based on an understanding of what happened and why, would conclude the exact opposite – that a single currency would be very destructive for some, if not most, of the 12 nations that were in the process of surrendering their currency sovereignty to join the Economic and Monetary Union.

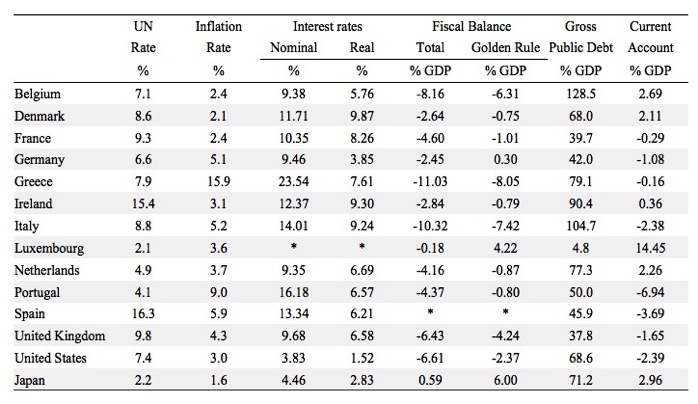

Once the ratification process was completed, attention turned to meeting the convergence criteria. Table 2 provides a snapshot of where the nations were in terms of the major convergence criteria in 1992. The unemployment rate, which was ignored in articulating what a desirable convergence should look like, is also shown. To put a finer point on it, the policy makers considered the unemployment rate (via its link to the economic growth rate) to be the ‘adjustment variable’ as they pursued policies designed to meet the demands of the convergence criteria. They knew that to reduce public debt ratios and fiscal deficits and bring inflation rates into line they would have to reduce domestic activity, given that their undertakings under the EMS in terms of maintaining the narrow exchange rate bands gave them no other source of adjustment. The logic of forcing the heavy adjustment work onto the domestic economy rather than the exchange rate was obvious – unemployment rates would have to rise for nations such as Belgium, Ireland, Greece, Italy, Portugal and the United Kingdom. And so they did. Belgium’s unemployment rate rose from 7.1 per cent in 1992 to 9.7 per cent in 1995; Greece from 7.9 to 9.2 per cent; Spain from 16.3 per cent to 20 per cent; France from 9.3 to 10.6 per cent; Italy from 8.8 to 11.2 per cent; the Netherlands from 4.9 to 7.1 per cent’ Portugal from 4.1 to 7.2 per cent as policy makers pushed their economies into an effort to meet the criteria.

With the large disparities across the 12 Member States in terms of the convergence criteria variables it was unimaginable that all the components of the convergence agreement could be met. For example, to maintain the exchange rates within the narrow tolerances agreed, some nations would have to increase interest rates, which would violate the undertakings with respect to maintaining narrow interest rate differentials to bring given the scale of the adjustments required.

Exchange rate adjustment was staring the policy makers and politicians in the face but they blithely chose to ignore it. Until September 1992 – that is.

Table 2 Convergence Criteria data, 1992

Source: AMECO database.

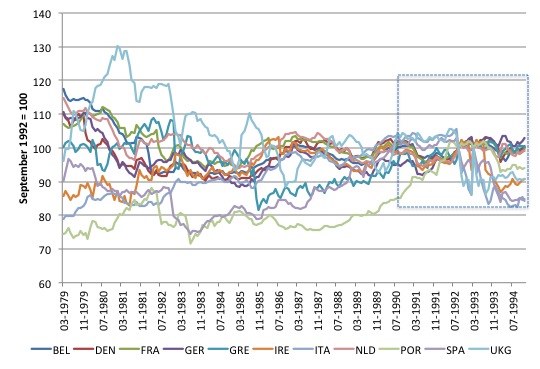

If that data didn’t convince you of how great the differences between the twelve economies were in 1992, then the next two should leave you with little doubt. They show what economists call ‘real effective exchange rates’ and the data shown in from the special measures compiled by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) in Switzerland.

The BIS publish the data on a monthly basis since January 1964, so we can see the movement in the real effective exchange rates over the entire period of the EMS, which began on March 1979. Real effective exchange rates measure how competitive a nation is relative to other nations in trade. They are essentially compiled by adjusting the actual exchange rate (called the nominal parity) by relative inflation rates. To understand the concept, consider the case of two nations with the same inflation rate, which means the prices of goods and services in each country are rising by the same rate.

If the exchange rate in Country A starts to depreciate against the Country B (which means that B’s rate is appreciating against A’s rate), then goods and services offered in trade by Country A to Country B (exports to B) will now be cheaper for residents in Country B, because their currency buys more of Country As currency. From the perspective of residents in Country A, goods and services bought from Country B (imports from B) will now be more expensive because their currency unit buys less of B’s currency. In this case, we conclude that country A is becoming more internationally competitive as a result of the nominal exchange rate change. Similarly, if the nominal parity was unchanged between Country A and Country B, but Country A becomes more productive and its costs of production fall, which leads to a decline in its inflation rate, then Country A’s international competitiveness will also rise (goods and services exported to other nations will be cheaper).

You could also have a situation where a nation’s currency is depreciating (which would boost competitiveness) but this is accompanied by a rise in its inflation rate relative to its trading partners (which would reduce competitiveness) and the net result might be no change in international competitiveness at all. The rising inflation could be driven exclusively by the rising import prices (in local currency terms) as the exchange rate depreciates. This is why nations that are experiencing currency depreciation like to ‘lock it in’ in real terms to benefit from the gain in competitiveness. Governments often try to negotiate deals with trade unions and firms to accept the higher import prices and the result drop in real incomes rather than try to recoup the real losses by pushing up wages and/or prices.

Real effective exchange rates take all these factors into account and provide a summary measure of movements in international competitiveness. If the real effective exchange rate rise, then we conclude that the nation is less internationally competitive and vice-versa.

Figure 2.1 shows the real effective exchange rates for the Maastricht Treaty nations from March 1979 to December 1993, indexed to 100 in September 1992. An index means we can set all the rates equal to 100 at some particular point (called the base period) and then watch what happens after that. The indexes allow us to compute percentage growth and also the use of the common base period aids comparisons of the growth processes across nations. If there are large differences between real effective exchange rates between nations this will show up in trade imbalances and, if permitted, the nominal exchange rate will adjust to reduce these trade deficits/surpluses. So a nation with a persistent and growing trade deficit as a result of declining international competitiveness will see its nominal exchange rate fall, which may improve its trade position as it becomes more competitiveness. I say ‘may’ because there are many factors at work which can complicate the adjustment process that follows a change in a nation’s nominal exchange rate. A nation facing the prospect of a depreciating/appreciating exchange rate as a result of its weak/strong trade position will also endure speculative attacks on its currency, which further push the exchange rate movements.

However, when the nations signed up for the EMS in March 1979, they were all obligated to keep the fluctuations in their exchange rates within 2.25 per cent plus or minus of the agreed parities (Italy was given a higher fluctuation band given its higher inflation and persistent trade deficits following the oil price hikes). This meant that a nation facing reduced international competitiveness had to cut costs (for example, constrain wage rises) to bring its inflation rate down and also constrain domestic demand to reduce growth in national income and GDP, which would lead to reduced spending on imports. It also led to persistently high unemployment. This was the period of the ‘Franc Fort’ (strong Franc), which defined French Government economic policy in terms of matching German inflation rates and other nations also followed suit.

As we have seen in our earlier discussion, the upshot was that there were many forced realignments as the central banks struggled to maintain the exchange rates within the narrow tolerances specified under the EMS rules. These realignments led to sharp fluctuations in real effective exchange rates, which is evident in Figure 2.1 in the early 1980s. After the Basel-Nyborg agreement was signed in 1987, which discouraged exchange rate realignment, nations were forced to rely much more on interest rate adjustments to maintain the parities. By increasing interest rates relative to their trading partners a nation would attract capital inflow which would increase demand for its currency and resolve the downward pressure. Of-course, the rising interest rates were detrimental to domestic economic activity as noted in the previous paragraph.

This period of exchange rate stability is also evident in the real effective exchange rates during the second-half of the 1980s. A false sense of stability emerged, which didn’t reflect any major convergence between the economies in economic performance. Speculative activity in foreign currency markets however was more subdued in this period as a result of the sense that central banks were committed to using domestic adjustment rather than exchange rate realignments to resolve trade imbalances. But the uncertainty started to build again as a result of the growing dissatisfaction with the Maastricht Treaty process, which came to a head during the ratification period.

Figure 2.1 Real effective exchange rates, Maastricht Treaty nations, March 1979 – December 1993, September 1992=100

Source: Bank of International Settlements.

It should also not be forgotten that capital controls were still in place during this period of relative stability, which prevented some of the speculative movements that could destabilise a nation’s exchange rate. Italy relied on capital controls extensively and only started to withdraw them in 1988 (Giavazzi and Giovannini, 1989; Eichengreen and Wyplosz, 1993). But the growing Monetarist dominance in economic policy that elevated the idea that the ‘free market’ sat on the right-hand side of God, hated capital controls and they were eventually eliminated as a policy choice for all nations. This began with the passing of the Single European Act of 1986, which aimed to create a single market in goods and services and capital, in stages by 1992, with capital controls to be abolished by July 1, 1990. Exceptions were made for Ireland and Spain (December 31, 1992) and Greece and Portugal (December 31, 1995).

The abolition of controls eliminated one policy tool that governments had to maintain stability and this would become evident in 1992. Eichengreen and Wyplosz (1993), among others recognised the bind that European governments were getting themselves into, when they coined the term “The Unstable EMS”. They noted (p. 52) “that the protracted process of negotiation and ratification allowed doubts to surface about whether the treaty would ever come into effect”. They also highlighted the “perverse incentives built into the treaty” (p. 52) as a further complicating factor. To meet the convergence criteria, nations had to maintain their currencies in narrow bands. But if a speculative attack which forced a nation to devalue (and thus breach the convergence rules) made transition to Stage III impossible, then what incentive did the nation have to maintain its policy austerity? At that point the speculative attacks becomes “self-fulfilling” (p. 52).

Eichengreen and Wyplosz (1993: 57) also argue that the capital controls “protected central banks’ reserves against speculative attacks” by reducing the possibility of the exchange rate being driven below the agreed fluctuation bands (which would require central banks to sell foreign currency in return for its own). This allowed the central banks to “retain some policy autonomy” (p. 57), in the sense that they could pursue domestic objectives such as economic growth and low unemployment, which may have also meant that a particular nation’s inflation rate was higher than its competitors. The capital controls gave them this leverage.

Once capital controls were eliminated, central banks became vulnerable as they had to focus policy on defending the nominal exchange rate parities. And with the rising instability associated with the treaty, this vulnerability became acute. The referendum failure in Denmark on June 2, 1992 brought some reality back into European financial markets in the sense that the false sense of currency stability between nations with very disparate inflation rates and levels of international competitiveness quickly changed. It had been true that after the Basle-Nyborg agreement in 1997 there had been no discretionary devaluations. But it was obvious that Italian and British competitiveness had been severely eroded by their higher inflation rates and that their currencies were substantially overvalued, particularly against the Deutsch Mark.

The first cab off the rank was the Italian Lira, which came under increased speculative scrutiny as the mid-year of 1992 approached. The US dollar was depreciating and reduced the competitiveness of European nations, with Italy the most impacted given its inflation rate was significantly higher. Within the logic of the EMS, the correct response would have been for the Italian government to devalue their currency by more than 10 per cent. But the Government was deeply divided over how it would go about meeting the convergence criteria and the Banca d’Italia resisted devaluation. The Italians instead attempted to maintain the exchange rate parity and raised interest rates sharply on September 4, 1992. At that point, short-term interest rates in Italy were already a growth-choking 15 per cent.

But that wasn’t enough and the Lira plunged below the low fluctuation band as investors moved funds out of Italy (mostly placing them in German Deutsche Marks). This, in turn, was placing pressure on the Bundesbank who were also trying to defend the Lira by selling the Mark. The Germans, as expected, felt that the growth in the supply of Marks could cause inflation in Germany and they were reluctant to hold the fort for too long.

Over the weekend September 12-13, 1992, there were meetings where the Italians, on the instigation of the German officials requested to be allowed to devalue (Szász (1999: 173). On September 13, 1992, the Lira was duly devalued by 3.5 per cent but this was actually a 7 per cent shift because the other currencies were revalued by 3.5 per cent. Szász (1999: 173) recounts “telephone conversations” where “it was decided to devalue the lira … by 7 per cent, disguised for reasons of prestige as a devaluation of … 3.5 per cent and a revaluation of the other currencies by 3.5 per cent”.

The British pound was also under sustained attack from speculators who were selling US dollars, Italian Lira and sterling and shifting massive volumes of funds into the Deutsche Mark.

[NEXT UP – BUNDESBANK INTRANSIGENCE, AND BLACK WEDNESDAY]

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

BBC (2002) ‘Not while I’m alive, he ain’t – Part 4’, Transcript from The Westminster Hour, Sunday April 21 2002. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/the_westminster_hour/1940421.stm

Eichengreen, B. and Wyplosz, C. (1993) ‘The Unstable EMS’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 51-143.

Giavazzi, F. and Giovannini, A. (1989) Limiting Exchange Rate Flexibility: The European Monetary System, Cambridge, MIT Press.

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments