At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 42

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

By the time they got to Maastricht …

The European Council meeting in Luxembourg, on June 28-29, 1991 noted the progress made by the two IGCs (on the economic and monetary union and political union). On October 25, 1991, some European Council members (President-in-Office Wim Kok, President Delors and Vice-President Christophersen) made statements to the European Parliament in Strasbourg. Wim Kok told the gathering that “Maastricht … was just seven weeks away” (European Community, 1990: 1) yet major issues were unresolved including final agreements on the reference values for the binding fiscal rules and the mechanisms that would curtail the yet to be specified excessive budgetary deficits. Even the single currency was not yet unanimously accepted. Further, how democracy could exist alongside an unelected and politically independent European Central Bank remained unresolved. In that regard, there “was no consensus among Member States over executive decisions and the role of the European Parliament” (European Community, 1990: 2).

Jacques Delors asked the question “Could the same criteria be used to judge the deficits of a mature economy and that of a developing economy?” (European Community, 1990: 2) and complicated matters by urging the discussion not to adopt a “solely arithmetical appreciation of deficits” (European Community, 1990: 2). In other words, universally binding numerical rules would unlikely be in the public interest.

The Dutch, in particular, were getting anxious about what might happen if the Maastricht Council meeting failed to reach agreement on the Treaty revisions. The former Executive Director of the Dutch Central Bank, André Szász was despairing of the process by the end of the 1990s, even though he played an important part of the move to the economic and monetary union in the early 1990s.

In his 1999 reflection, ‘The Road to European Monetary Union’, Szász wrote that the “early prospect of German unification came as a shock” (p. 144) for the British and French. He says that the French responded to the implied loss of power within Europe by accelerating their call for monetary union, while the British increasingly distanced itself from continental Europe. France also tried to use the simultaneous Intergovernmental Conferences to argue for a supranational “‘Economic Government’ in parallel to the European Central Bank”, which would be a ‘democratic’ institution that would “execute the main elements of economic policy” (Szász, 1999: 157). But the French were not united on this demand (Howarth, 2000). Interestingly, the Dutch and German negotiators favoured an independent supranational economic polic making body to parallel the new central bank, but didn’t want this to be part of the a “reinforced Ecofin Council” and thus subordinate to the European Council, which was the preference of France (p. 157). Germany and the Netherlands considered, in Szász’s view, that such a body would be able could run excessive deficits and then to divert political pressure onto the ECB if the latter raised interest rates in the pursuit of its price stability goals (pp. 157-58).

The political implications of German reunification, however, concentrated minds. In November 1991, Szász urged the parties to forge an agreement because he believed that the new Germany, already a successful federal state, might go it alone (Baun, 2001: 620). The New York Times ran a story on November 16, 1991 – ‘France and Germany warn Britain on Europe’ (Kinzer, 1991) which quoted Helmut Kohl as saying that the upcoming Maastricht meetings were “a fateful hour for Europe” and that it would be

“a catastrophe for European development … the beginning of the collapse of our community” if the Treaty talks failed.

On December 11, 1991, the troupe rolled into Maastricht for the European Council meeting that would finally take the decision to recreate the European Community with a new treaty centred on the introduction of the economic and monetary union. Nations who joined the EMU would cede their currency issuing capacities to a newly created and independent European Central Bank, prevent that institution from playing a defensive role in times of crisis (‘monetary financing of deficits’) and agree to constrain their own fiscal freedoms to such a degree that they could no longer exercise their responsibilities to consistently maintain strong economic and employment growth. Not only did they agree to replace their own currencies with what was effectively a foreign currency but they also exposed themselves to the whims of the private bond markets who existed only to make profits without regard for national goals such as full employment. At this one European Council meeting, the deflationary bias of the Bundesbank became the dominant policy paradigm for Europe at large, except that Germany’s export strength was not shared.

The Germans and the Dutch held their position on the need for binding fiscal rules with sanctions for breaches. The British wanted no rules because they correctly knew they compromised the democratic legitimacy of the national government. There were curious conflicts among conservatives over this question. The liberal view as the there was no need for rules because once the governments lost their currency-issuing capacity (and many were still selling bonds to their central banks in return for cash) the private bond markets would stop lending to a profligate government. The alternative view was that once a nation encountered ‘funding’ constraints, which threatened the financial system given the increased default risk, that the pressure for bailouts would be intense. The central bankers were leading the charge for tight fiscal constraints to avoid “overburdening monetary policy” (in other words, forcing monetary policy to fight higher rates of inflation with higher than otherwise interest rates) (Szász, 1999: 159).

Going into Maastricht, the ‘golden rule’ was still on the table given it allowed for differences in national commitments to the provision of public infrastructure. But Szász (1999: 159) wrote that “in the end the golden rule proved unacceptable” and attention then turned to using arbitrary celings on deficits and publc debt ratios. He concludes that the agreement to set the reference values to 3 per cent (deficits to GDP) and 60 per cent (gross public debt to GDP) “was a compromise” (p. 159) to bring together those who wanted a higher allowable deficit figure and others who wanted legally-binding balanced budget. Meet somewhere in the middle! The public debt ratio appeared to be a reflection of the current situation and had not science backing it.

Szász (1999: 159-60) is clear:

The members of the Monetary Committee were aware of the rather arbitrary nature of these figures. They realised that the judgement whether budget deficits were excessive could not be mechanical, and this awareness is reflected in the procedure incorporated in the Treaty. At the same time, the Germans and Dutch in particular felt that the alternative would have been to leave this judgement entirely to the discretion of the Council. This would be an insufficient basis for Monetary Union, given the tendency in the Council – so often observed in the past – to avoid political confrontation.

Whether it was the French’s long-standing 3 per cent limit that ruled is unclear given that they were arguing in the negotiation phase for looser guidelines than would be provided by the ‘golden rule’ (Schönfelder and Thiel, 1994). Other claims (aired on the Franco-German TV channel, ARTE) concluded that at the time of the Maastricht Council meeting, the 3 per cent limit was around the deficits currently being run by Germany at 2.8 per cent and France at 3 percent. While the exact reason for selecting the 3 per cent limit was not to be found in any economic theory, it was obvious that the arbitrariness did not reflect reasonable deficit ranges.

Writing in 1999, Szász speculated that the 3 per cent limit would be breached “as soon as an adverse cyclical situation presents itself” (p. 160). If that happened across the union, then any sanctions process would lose meaning. It was clear to all and sundry, as they went into Maastricht that the potential for the union to collapse under its own compromised and flawed design was high. But the politics rules and careers had to be maintained or made! The folly that masqueraded as responsible leadership would within 15 years inflict untold misery on the most disadvantaged citizens in many European countries. But in 1991, as December approached the bluster and rhetoric was pushing the throng in one direction only. The cliff would come later.

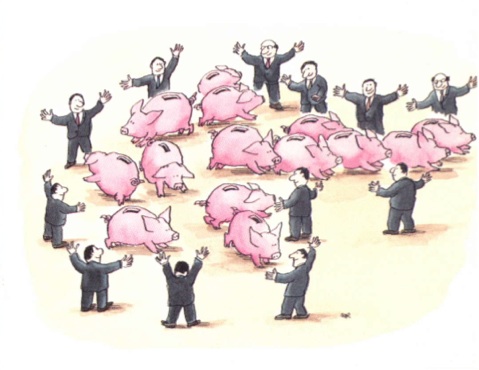

[The following cartoon is for your interest only – IT WILL NOT APPEAR IN THE FINAL BOOK DRAFT]

Its a man’s world – with some fat PIGS – talking up the disaster

Source: European Commission (1991) ‘Economic and Monetary Union: Europe on the Move’, page 5. Note that there are 14 piggy banks but only 12 nations.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

European Community (1990) ‘European Parliament, Rapid Information Note, SP (91) 2669, 21-25 October 1991 Plenary Session’, October 25, 1991. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/emu_history/documentation/chapter13/19911025en07epdebateonemu.pdf

Howarth, D.J. (2000) The French road to European monetary union Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Kinzer, S. (1991) ‘France and Germany warn Britain on Europe’, New York Times, November 16, 1991.

Schönfelder, W. and Thiel, E. (1994) Eine Markt – Eine Währung, Die Verhandlungen zur Europäischen Wirtschafts- und Währungsunion, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

Szász A. (1999) The Road to European Monetary Union, Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan.

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The British wanted no rules because they correctly knew they compromised the democratic legitimacy of the national government

“Citation needed”, as the wikipedia compilers are wont to write.

Minor point:

‘would unlikely be’

I would amend this to ‘were unlikely to be’.

Jobs Guarantee idea is advancing in leaps and bounds in Britain: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-26506522

Under this cheme, anyone under 25 would be offered a job after one year of unemployment, and anyone over 25 would be offered a job after two years of unemployment.

There seems to be some internal wrangling inside the labour party about the scope and scale of this policy. No doubt the idea came from MMT people. That seems to suggest there are certain factions inside the labour party that do not belieave the government faces a funding constraint, even tough the leadership does.

I think PZ is being too optimistic in thinking that there is a pro-MMT “faction” inside the UK Labour Party, although there may be individual members who are trying to increase general awareness of MMT. Here is a Smith Instute paper, written by a senior member of the Labour Party and published October 2012: “Job Guarantee: a right and responsibility to work”.

http://www.smith-institute.org.uk/file/Job%20Guarantee.pdf