At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 35

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY]

The Wall collapses – “I love Germany so much, that I prefer there to be two of them”

The French novelist, François Mauriac wrote during the Cold War that “J’aime tellement l’Allemagne que je préfère qu’il y en ait deux” (“I love Germany so much, that I prefer there to be two of them”) (Le Monde diplomatique, 2011). While this hostility was embedded in the European nations that Germany had invaded, the tension that it caused ultimately led to the Treaty of Maastricht, but not without some very bitter political interactions.

Before the European Council were able to convene their conference to map out the second and third phases on the Delors Plan, political events in the East overtook them. On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall was torn down and suddenly, an unanticipated new agenda cut across the monetary union plans. The Cold War had dampened the sensitivity elsewhere in Europe about Germany, in that it was attenuated by such developments as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in 1949. Any West German military ambitions would be difficult to escalate under this Post World War II institutional framework, not that there was any hint that these ambitions were harboured. The French, in particular, though, were ever wary, if not paranoid, on this issue. The Them (communist world) versus Us (the ‘Free world’) type narrative constantly spun by the US and its allies also concentrated minds away from the issue of German domination.

But that all changed when the ‘Wall’ collapsed and with German reunification back in vogue, the rest of Europe started to ask what life would be like if Germany became ‘too powerful’. It revived the “German question” (Delors, 1989b). A scan of the French press at the time reveals a deep national insecurity about the the prospects of Germany becoming bigger again (Lind, 2011). Even at the political level, this suspicion was evident.

On October 17, 1989, European Commission President Delors gave a speech to the College of Europe in Bruges and discussed the “German question” (Delors, 1989b). While berating the “embittered”, the “fatalistic”, and those “shackled by resignedness” (a reference to the increasing paranoia about a possible German reunification), Delors concluded that “the only acceptable and satisfactory answer to the German question” was to strengthen the “federalist traits of the Community” (Delors, 1989b: 11).

But there was some way to go before France and Britain would accept that. Mitterand, using his prerogatives as the French Presidency of the European Commission, called an informal summit of the heads of government at the Élysée Palace on November 18, 1989. European Commission President Jacques Delors was also invited. At that meeting, Mitterand demanded that German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl clarify the policy objectives of Germany, in particular, with respect to borders.

Across the Channel, the British were similarly hostile to the prospect of an enlarged Germany. Margaret Thatcher, who attended the November Paris meeting, later recalled that Mitterand has posed a “number of questions, including whether the issue of borders in Europe should be open for discussion” (Thatcher, 1993: 759). Kohl reponded by saying that “there should be no discussion of borders but that the people of Germany must be allowed to decide their future for themselves” (Thatcher, 1993: 793). In her own response, Thatcher recalled that she said “There must be no question of changing borders” (Thatcher, 1993: 793-94). Thatcher also admitted to extreme anti-German views in her 1993 memoirs. She wrote that she eschewed the notion if a “collective guilt” among the Germans but that German’s “national character” was “by its very nature a destabilizing force rather than a stabilizing force in Europe” (Thatcher, 1993: 791).

On November 28, 1989, just 10 days after the Paris meeting, Kohl unilaterally announced in a speech to the Bundestag, that Germany would pursue a “Zehn-Punkte-Programm zur Überwindung der Teilung Deutschlands und Europas” (“Ten-Point Program to overcome the division of Germany and Europe” (Deutscher Bundestag, 1989).

Mitterand and Thatcher then met informally in Strasbourg on Friday, December 8 during the European Council meeting. Thatcher recalled two meetings with Mitterand, in which he was openly hostile towards Kohl’s ten-point plan (Thatcher, 1993: 796-97). She said of the meetings that “It seemed to be that although we had not discovered the means, at least we both had to the will to check the German juggernaut. That was a start” (Thatcher, 1993: 797).

François Mitterand scheduled a hasty trip in December 1989 to meet with Mikhail Gorbachev in Kiev, who he knew was opposed to the German re-unification. Lind (2011: 140) quotes Stanley Hoffmann, who said the Kiev meeting “could not help but invoke the ghosts of Franco-Russian allegiances against the German danger and of German obsessions about encirclement”. She also quotes Edouard Husson as saying that “François Mitterand’s entire European policy can be explained by one simple motive: the obsessive fear of German power” (Lind, 2011: 140). Judt (2005: 640) noted that Mitterand initially sought to stop the re-unification by “trying to convince Soviet leaders that, as traditional allies, France and Russia had a common interest in blocking German ambitions. Indeed, the French were banking on Gorbachev to veto German unity”.

Belgian Prime Minister at the time, Wilfried Martens, who was “strongly” in favour of German re-unification, recalled that “the fall of the Berlin Wall required a mental readjustment” and Kohl’s Bundestag announcement “encouraged everyone … to get a move on”. Marten stood apart from the anti-German hysteria spouted by his colleagues and said that “Kohl wanted to embed German reunification with a united Europe. This concurred with his deepest convictions. He wanted to strengthen and broaden the Community with all that this implied at the time: the EMU and the Social Charter, and, further in the future, the European Political Union …” (Martens, 2009: 100). He also noted that the Strasbourg European Council meeting over December 8-9, 1989 was firmly focused on European integration and in the Council report managed to construct the German reunification within “the principle of ‘not a German Europe, but a European Germany'” (Marten, 2009: 101).

Mitterand eventually fell into line with the idea that German reunification was part of the increased European integration. Garton Ash (1994: 390) concluded that “This Franco-German understanding was the single most important driving force behind the inter-governmental conferences on what was loosely called the European political and monetary union, and hence of the Maastricht treaty”. Germany was becoming a ‘European Germany’ although the discussions about the economic and monetary union might lead to the conclusion that a ‘German Europe’ was being developed.

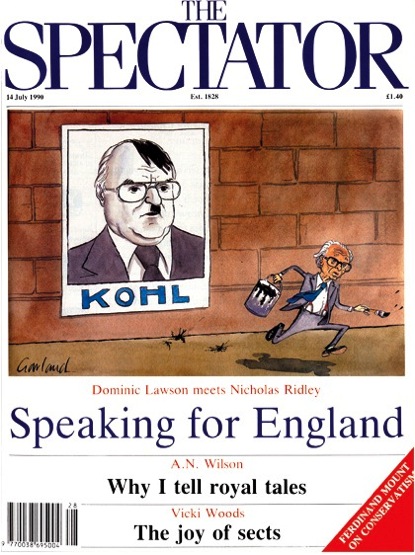

This was clearly the view of the British. Thatcher, could not accept Mitterand’s falling into line on a ‘European Germany’. Clearly, there were on-going tensions within the British government about the reunification. In July 1990, the British paranoia became starkly defined in an interview conducted by the editor of the conservative British magazine, The Spectator, Dominic Lawson interviewed with the then British Trade and Industry Secretary, Nicholas Ridley who was considered to be a close confidant to Margaret Thatcher. The interview was published in the magazine’s July 14, 1990 issue (Lawson, 1990). It led to the forced resignation of Ridley but disclosed the inner sentiments of the Thatcher’s government. It was so explosive that Lawson subsequently clarified that Ridley was sober and knew the tape was rolling (Stead, 1990). The German called the views expressed “scandalous and incomprehensible” (Longworth, 1990).

Lawson noted that the Bundesbank President Klaus-Otto Pöhl was about to visit “England to preach the joys of a joint European monetary policy” (Lawson, 1990: 8). The following is an edited version of what followed:

Ridley: This is all a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe. It has to be thwarted. This rushed takeover by the Germans on the worst possible basis, with the French behaving like poodles to the Germans, is absolutely intolerable.

Lawson: Excuse me, but in what way are moves toward monetary union, “The Germans trying to take over the whole of Europe”?

Ridley: The deutschmark is always going to be the strongest currency, because of their habits (last phrase was emphasised in original).

Lawson: But Mr.Ridley, it’s surely not axiomatic that the German currency will always be the strongest?

Ridley: It’s because of the Germans (last word emphasised).

Lawson: But the European Community is not just the Germans.

Ridley: When I look at the institutions to which it is proposed that sovereignty is to be handed over, I’m aghast. Seventeen unelected reject politicians … with no accountability to anybody, who are not responsible for raising taxes, just spending money, who are pandered to by a supine parliament … I’m not against giving up sovereignty in principle, but not to this lot. You might just as well give it to Adolf Hitler, frankly …

Lawson: But surely Herr Kohl is preferable to Herr Hitler. He’s not going to bomb us after all.

Ridley: Im not sure I wouldn’t rather have … the shelters and the chance to fight back, than simply being taken over by … economics (the last word emphasised) …

[Later Ridley attacked the Bundesbank again]

Ridley: I don’t know about the German economy. It’s the German people (last word emphasised). They’re already running most of the Community. I mean they pay half of the countries. Ireland gets 6 per cent of their gross domestic product this way. When’s Ireland going to stand up to the Germans?

[THE FOLLOWING WILL NOT APPEAR IN THE BOOK BUT IS INCLUDED HERE FOR YOUR INTEREST – IT IS THE FRONT COVER OF THE JULY 14, 1990 SPECTATOR SHOWING HELMUT KOHL DEPICTED AS HITLER]

As an aside, The Spectator no longer makes the July 14, 1990 edition available in its archives. You can, however, find it in the archives of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation (see references).

[TO BE CONTINUED]

[TOMORROW WE MOVE ONTO TREATY OF MAASTRICHT]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Delors, J. (1989b) ‘Address at the College of Europe, Bruges, October 17, 1989’, Europe Documents. http://www.cvce.eu/obj/address_given_by_jacques_delors_bruges_17_october_1989-en-5bbb1452-92c7-474b- a7cf-a2d281898295.html

Deutscher Bundestag (1989) ‘Zehn-Punkte-Programm 1989’, Streifzug durch die Geschichte. http://webarchiv.bundestag.de/archive/2009/0109/geschichte/parlhist/dokumente/dok09.html

Garton Ash, T. (1994) In Europe’s Name: Germany and the Divided Continent, New York, Vintage (re-issue, first published 1993).

Judt, T. (2005) Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, London, Penguin Books.

Kohl, H. (2005) Erinnerungen 1982-1990, München, Droemer Knaur Verlag.

Lawson, D. (1990) ‘Saying the unsayable about the Germans’, The Spectator, July 14, 1990. http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/111535

Le Monde diplomatique (2011) ‘Maniere de voir, No. 116’, Avril-mai, 2011. http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/mav/116/

Lind, J. (2011) Sorry States: Apologies in International Politics, Ithaca, Cornell University Press.

Longworth, R.C. (1990) ‘Ridley`s (oops) Believe It Or Not’, Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1990. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1990-07-13/news/9002270181_1_dominic-lawson-nicholas-ridley-german-bundesbank

Martens, W. (2009) Europe: I Struggle, I Overcome, Dordrecht, Springer.

Stead, D. (1990) ‘Magazine of the Right That Tripped Up a Tory’, New York Times, July 19, 1990.http://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/19/arts/magazine-of-the-right-that-tripped-up-a-tory.html

Thatcher, M. (1993) The Downing Street Years, London. Harper Collins.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill:

Dominic Lawson was the editor of the Spectator at the time; not his father, Nigel.

Dear Brian Lilley (at 2014/02/26 at 18:29)

Yes, true. Thanks. I have fixed it now.

best wishes

bill