At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 23

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[PRIOR MATERIAL HERE FOR CHAPTER 1]

Next stop – “L’Europe se fera par la monnaie ou ne se fera pas” – the European Monetary System (EMS)

[PRIOR MATERIAL HERE FOR THIS SECTION]

[COMPLETELY REWRITTEN SECTION FROM YESTERDAY – THE REWRITE IS TO CLARIFY MATTERS AND CREATE A DENSER ACCOUNT TO ENRICH THE NARRATIVE – I HAD SOME NOTES IN ANOTHER OFFICE THAT I WAS WORKING OUT OF TODAY WHICH ACCOUNTS FOR THE ADDITIONAL MATERIAL THAT IS WEAVED INTO YESTERDAY’S TEXT – I AM HAPPIER WITH IT AT LEAST]

While Schmidt was increasingly seeking a ‘European’ solution to Germany’s economic difficulties, the simmering conflict between the German government and the Bundesbank continued. The popularity of German politicians in the Post World War II period was influenced by both how stable the domestic inflation rate was and how low the unemployment rate was. Increases in either led to social discord. The Bundesbank Act focused the Bank on the former goal but at the expense of the latter, given that inflation was controlled by restricting total spending in the economy. When Willy Brandt began the Keynesian era, and Helmut Schmidt followed, the conflict between government and bank was never far from the surface. The government was more interested in currency stability in the world foreign exchange markets while the Bank was more focused on domestic price stability (Hetzel, 2002: 12) and the two ambitions were not necessarily consistent at all times. Hetzel cites Johnson (1998: 70) who said a Bundesbank official considered this struggle to be “a Glaubenskrieg (religious war) of Wagnerian proportions.”

The European ambitions of Schmidt inflamed these tensions within the Germany economic policy circles. While the stagflation that followed the first oil crisis had consolidated the Bundesbank’s domestic price stability priorities as the Federal government reduced its embrace of Keynesian expansion and all but abandoned low unemployment rates as an objective, the move to increased economic and monetary integration within Europe was seen by the Bundesbank as a threat to their independence (Hetzel, 1998). As we will see, the Bundesbank exploited the vagaries of the plan for the introduction of the European Monetary System (EMS) and firmly defined their place in a European monetary system on their own terms. This strategy was important for what was to come post Maastricht. But first we should briefly trace the stages towards that the creation of the EMS.

Schmidt and Giscard d’Estaing, who both came to office in 1974 at a time the global economy was in chaos as a result of the oil crisis, stagflation and on-going currency speculation. For the first time, the Germans found a French ally who was willing to advance the ‘European’ issue. Once again the heightened motivation for monetary integration was directly related to the weakening of the US dollar. In the period after the abandonment of the Smithsonian Agreement, the US government had clearly allowed the US dollar to fall and this was interpreted by the Europeans as an insouciance to the problems that the currency instability caused for the customs union and the CAP, which required currency stability.

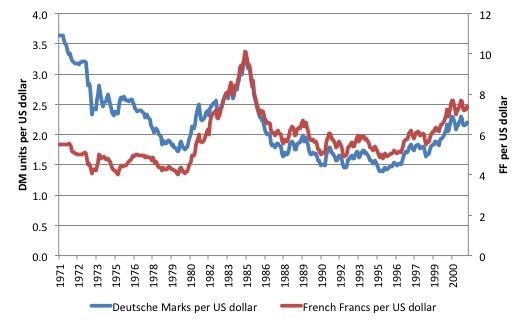

Figure 1.3 shows the movement in the Deutsche Mark and French Franc exchange rates against the US dollar from January 1971 to December 2001. Throughout the 1970s, the Mark was appreciating against the US dollar and the French Franc. The strains reached breaking point when the Deutsche Mark appreciated strongly against the US dollar in 1977 and early 1978 and the French Franc simultaneously weakened against the Mark. The perverse currency movements were imposing costs on the German export industries and provided the motivation for Germany to seek a better way of shifting some of the adjustment burden from its economy onto the weaker currencies in European trade partners. In other words, it wanted to reduce the asymmetry in the system that was biased against Germany.

It is interesting that the idea of assymetry itself was contestable. The German view was supported by Denmark and the Netherlands and was focused on avoiding import price inflation from higher inflation nations under a fixed exchange rate system, a problem that beset the latter years of the Bretton Woods system. Further, the Bundesbank feared that a lack of discipline in the weaker currency nations would force it to take responsibility for maintaining the parities and, in the context of an appreciating Deutsche Mark, this would compromise their capacity to control the money supply and expose Germany to higher inflation. Conversely, the weaker currency nations (France, Italy, the United Kingdom) were concerned that they would have to acccept the restrictive Bundesbank monetary policy settings or elseface major capital outflows. Under the ‘snake’ the dominance of German monetary policy forced its trading partners to endure higher unemployment than they desired (Houben, 2000). The upshot was that all parties had incentives, for different reasons, to move to a more symmetrical system of exchange rate management.

Both Schmidt and Giscard d’Estaing also considered the currency instability to be a drag on the growth in European industrial production, which they considered a major cause of the persistently high unemployment that had beset Europe after the first oil price shock (Loriaux, 1991). They might have also implicated the excessively tight monetary policy and the lack of fiscal expansion but the growing dominance of the neo-liberal ideology in this period precluded such wisdom (see Modigliani, 2000).

Figure 1.3 Deutsche Mark, French Franc US dollar parities, January 1971 to December 2001

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, FRED economic data, Monthly data as averages of daily figures.

Further, as discussed earlier, the creation of the customs union (the free movement of goods and services under the Treaty of Rome) and the harmonisation of agricultural prices under the CAP logically required a system of fixed exchange rates or, at least, a degree of currency stability. Currency instability within this type of ‘economic zone’ would mean that exporters would encounter costs by having to continually adjust their foreign currency prices and there would be incentives to engage in across-border arbitrage (buying cheap in one currency on one side of the border and selling for profit in another currency on the other side of the border) which would undermine local suppliers. Further without currency stability, the setting of common prices was vexed and the ad hoc solution introduced was the complex system of green rates.

The currency instability combined with the persistent balance of payments deficits in many European nations led nations such as Italy, Denmark and the United Kingdom to defy EEC rules regarding free trade (under the customs union) and impose import restrictions. The introduction of the Italian import deposit (which required importers to place funds in advance with the Italian Foreign Exchange Office) in 1976, ostensibly in response to its balance of payments problems caused by the oil price rises, was seen as a basic challenge to the concept of freedom of movement of goods and services, a foundation stone of the custom union. The policy caused consternation among its European exporters and raised accusations of a return to the ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ strategies that haunted world trade during the Great Depression. Unilateral imposts such as the deposit scheme were self-defeating if all nations followed suit. The global result would be a decline in overall trade and no change in the capacity of the nation to deal with the deficits caused by the need to pay higher prices for oil.

The matter led to Commission v Italy (Case 95/81, 1982) in the European Court where Italy argued the deposit scheme was in fact “part of monetary policy” (Case 95/81, 1982: 2191) and therefore legal under Article 104 of the Treaty. The Italians also argued it was allowable under “the concept of public policy” (Article 36) (Case 95/81, 1982: 2192), which related to the government’s right to protect its currency sovereignty. The French government supported Italy in its claim that a “Member States must be able to combat … [speculative attacks on its currency]” (Case 95/81, 1982: 2194) using various methods including the deposit scheme in question. While the Italian government lost that case, the general point was that the currency instability was undermining the legal framework of the ‘European Project’ that had to that date been implemented (in the case the customs union).

Schmidt and Giscard d’Estaing, met in relative secrecy in early 1978 to develop a joint strategy to replace the ineffectual ‘snake’ with a more integrated level of monetary cooperation. The UK were early participants in these dicussions but dropped out early. Notably, the Bundesbank Council and the European Council (apart from Roy Jenkins) were not privy to these meetings (Kaelberer, 2001). After working out a deal that both nations could live with, the two leaders unveiled their plan for a renewed attempt to introduce a European Monetary System at the European Council summit in Copenhagen on April 7 and 8. The proposal became reality at the European Council meeting in Bremen on July 6-7, 1979, when the leaders decided to push ahead with the creation of a European Monetary System along the lines laid out in Copenhagen. In its ‘Conclusions’ (European Council, 1978a: 17), the European Council argued that the “serious disruptions of the world economy, especially since the end of 1973” required Europe to take a “common approach … to achieve … a considerably higher rate of economic growth and thus reduce the level of unemployment by fighting inflation” (17). This would be achieved by “establishing a greater degree of monetary stability” among other things (p.17) which would require “the creation of a closer monetary cooperation” (p.18). In effect they wanted to bolster the ‘snake’ which they confirmed would “remain fully intact” (p.18).

Annex IV of the Council conclusions outlined the proposed design of the EMS, which would be “at least as strict as the ‘snake'” (p.20). Interventions to stabilise currencies within the snake would “be in the currencies of participating countries” and changes “in central rates” would be mutually agreed in advance. This represented a change to the existing ‘snake’, which allowed individual nations to alter their own parities.

The EMS would define the European currency unit (ECU), which was effectively the same as the previously created European unit of Account (EUA). The ECU would thus be the benchmark accounting value against gold against which other currencies would be paired. It would also be “used as a means of settlement between the EEC monetary authorities” (p.20). The ECU would reflect a basket of European currencies and each participating central bank would subscribe 20 per cent of their US dollar and gold reserves to establishing the initial pooled ECU fund. Initially, this allocation of ECUs to the Member States would be administered through the EMCF, established in 1972 as part of the ‘snake’.

The proposal also extended the European credit facilities available to central banks to make it easier to maintain the agreed parity ranges. For example, the Very Short-Term Financing (VSTF) facility was designed to automatically extend credit to a nation which required funds to defend its currency.

On the question of symmetry, the proposal to create the so-called ‘bi-lateral parity grid’ based on the individual currency values expressed in terms of the ECU. This just meant that each if each currency was valued against the common unit (the ECU), then they could all be valued against each other. The French, particularly, wanted the ECU to be “at the center of the system” (European Council, 1978a: Annex, 5) and be used as the intervention unit because they assessed it would reduce the importance of the Deutsche Mark. Germany opposed the use of ECU as the basis for intervention for various reasons, which need not concern us here. It was, of-course keen to set up a system that would free the Bundesbank from having to bear all the responsibility of maintaining parities in the face of on-going upward pressure on the Deutsche Mark (Piodi, 2012). In this context, there were on-going disputes about the creation of a central fund (that is, a central bank) that could use the ECUs to intervene to maintain parities.

The compromise that emerged – the ‘Belgian compromise’ – was the so-called Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) based on the ‘bi-lateral parity grid’ supplemented by a ‘divergence indicator’, an ‘early warning’ threshold, which created, in a formal sense, the appearance of symmetry in the proposed system. The agreed plan was that each currency could fluctuate against another by plus or minus 2.25 per cent. When either the upper or lower limit was reached (if currency A reached its upper limit of 2.25 per cent, the other currency would be at the lower limit of 2.25 per cent) the central banks of the relevant Member States would have to undertake foreign exchange transactions to bring the bi-lateral parity back into the acceptable range. The proposed intervention was to be triggered in the ERM by the so-called ‘divergent indicator’ (set at 75 per cent of the divergence margin). In practice, as we will see, the ‘indicator’ was never really functional.

The intervention was supposed to be symmetrical because when two currencies were in danger of breaching the limits of the allowable bi-lateral fluctuations, both nations would intervene. So, for example, if the French Franc reached the lower band of its parity against the Deutsche Mark the latter would have reached the upper band of its agreed parity against the Franc. This would mean that both the Bundesbank and the Banque de France would have to sell Deutsche Marks and buy Francs in the foreign exchange markets simultaneously. In theory, there would be less pressure on any one currency to adjust and less monetary disturbance in the respective economies. The EMS should be seen as a formal linking of the various Member State currencies and, in that sense, was a very limited development. In reality, the adjustment process was not symmetric because the liquidity effects of the respective interventions were quite different.

If, for example, a nation’s currency was depreciating against the Deutsche Mark, it either had to have Mark-reserves or access funds through the VSTF facility. Some interventions were made using US dollars but mostly bi-lateral intervention was the norm early on in the arrangement (Ungerer et al., 1983). VSTF calls were recorded as a debt that had to be paid back in foreign currencies within 45 days. To ensure solvency, therefore, nations facing depreciating currencies had to effectively increase their interest rates or devalue. For Germany, however, while it had to sell its own currency and acquire, say French Francs, to push its parity down below the upper limit against the Franc, the accounting rules of the system meant that gave the Bundesbank a VSTF credit and this was debited against the Banque de France, in the same way as the French intervention. But the important point was that this placed no pressure on the Bundesbank to alter its interest rates. In other words, just as the adjustment under the Bretton Woods system always fell on the nations with balance of payments deficits (weaker currencies) and required them to reduce domestic growth and increase unemployment in order to ease the downward pressure on their currencies, the same asymmetric biases were built into the EMS.

Piodi (2012: 38) notes that the European Parliament gave the Bremen proposal “a cool reception” and emphasised that the establishment of a ECU fund “is not sufficient for the success of the European Monetary System” as a path to full economic and monetary union unless it is accompanied by common economic policy is agreed and the convergent economic policies of the Member States eliminated. This concern repeats itself throughout the several decades of debate in Europe about the viability of the economic and monetary union and was also ignored, as we will see, in the final chapter that began at Maastricht in 1991.

On December 5, 1978, the European Council met in Brussels and agreed to set up the European Monetary System (EMS) along the lines outlined at the Bremen summit (European Council, 1978b) which followed the so-called Franco-German initiative taken at Copenhagen in April 1978 by Helmut Schmidt and Giscard d’Estaing. It won’t surprise the reader to learn that the system eventually found itself in crisis and instead of abandoning the almost impossible idea of tying these disparate European economies together into a functioning fixed-exchange rate currency zone, the European political leaders began the rocky road to Maastricht with a compromised EMS and the creation of the Delors Committee. But first, we have to tell the story.

The first part of that story is that the December agreement was less than complete and only considered itself to be dealing “primarily with the initial phase of the EMS” (European Council, 1978b: 114). What this meant was that the all important issue of the creation of a European central bank was deferred. There remained deep disagreement between the French and the Germans about the creation and operations of the European Monetary Fund as a type of European-wide central bank. The Council resolution in December 1978 deferred the creation of the Fund, which would replace the ECMF and use the ECU as a reserve asset and a means of settlement, for a period of up to two years so that “adequate legislation at the Community as well as the national level” can be introduced (European Council, 1978b: 2). As history tells us the implicit next phase in the Council resolution was never implemented. The Germans didn’t want the Fund to become have central banking functions given that this would compromise the Bundesbank’s capacity to maintain price stability. Other nations feared the creation of an independent fund would compromise their sovereignty. Piodi (2012: 41) says “there was the fear that the European Monetary Fund would create international liquidity” and this could be inflationary. The compromise was to defer these issues for the second phase and so no central bank for Europe was created which then raised issues as to what responsibility the Bundesbank and the Banque de France would have in ensuring the currency parities were maintained (Hetzel, 1998).

The EMS in practice

The EMS came into operation on March 13, 1979 despite it being agreed at the December Brussels Council Meeting that it would start on January 1, 1979 (European Council, 1978b).

[TO BE CONTINUED]

[WE ARE MOVING THEN TOWARDS THE DELORS REPORT IN THE LATE 1980s AND THE TREATY OF MAASTRICHT – THINGS WILL FLOW MORE QUICKLY AFTER THAT – I HOPE!]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Case 95/81 Commission v. Italy [1982] ECR 2187 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:61981CJ0095:EN:PDF

European Council (1978a) ‘The European Council Bremen Summit’, July 6-7, 1978. http://aei.pitt.edu/1454/1/Bremen_July_1978.pdf

European Council (1978b) ‘The European Council Brussels Summit’, December 5-6, 1978. http://aei.pitt.edu/1440/1/Copenhagen_1978.pdf

Houben, A (2000) The Evolution of Monetary Policy Strategies in Europe, Dordrecht, Springer.

Kaelberer, M. (2001) Money and Power in Europe, Albany, State University of New York Press.

Loriaux, M. (1991) France After Hegemony: International Change and Financial Reform, Ithaca, Cornell University Press.

Modigliani, F. (2000). ‘Europe’s Economic Problems’, Carpe Oeconomiam Papers in Economics, 3rd Monetary and Finance Lecture, Freiburg, April 6.

Piodi, F. (2012) ‘The Long Road to the Euro’, European Parliament, Directorate-General for the Presidency, Archive and Documentation Centre, 8, February.

Ungerer, H., Evans, O. and Nyberg, P. (1983) ‘The European Monetary System: The Experience, 1979-82’, Occasional Paper No. 19, International Monetary Fund.

Hi Bill,

When you get more time I was wondering if you could write a piece on the relationship between trade and budget balances. It all seems fairly straightforward using a three sector analysis but it strikes me that nearly all of those who are arguing for a govt budget deficit reduction have no idea just how closely linked they are. ie You can’t reduce your budget deficit or run a surplus without doing something about the trade imbalance.

A simple check on Wiki of governments with large budget surpluses shows that they they all have export surpluses too. Same with large deficits too.

Of course this may be relevant to your European book too. The Euro works fine for net exporters like Germany and the Netherlands, but its a disaster for net importers. It would have been a disaster for the UK, had they adopted it.

Good Luck with your book,

Peter