At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Options for Europe – Part 14

The title is my current working title for a book I am finalising over the next few months on the Eurozone. If all goes well (and it should) it will be published in both Italian and English by very well-known publishers. The publication date for the Italian edition is tentatively late April to early May 2014.

You can access the entire sequence of blogs in this series through the – Euro book Category.

I cannot guarantee the sequence of daily additions will make sense overall because at times I will go back and fill in bits (that I needed library access or whatever for). But you should be able to pick up the thread over time although the full edited version will only be available in the final book (obviously).

[PRIOR MATERIAL HERE FOR CHAPTER 1]

[WITH SMITHSONIAN SIGNED OPTIMISM DIDN’T LAST LONG – THE EUROPEANS THEN WENT THEIR OWN WAY – WHICH ALSO DIDN’T LAST LONG – THE NARRATIVE CONTINUES]

[NEW MATERIAL TODAY FOLLOWS]

The Basel Accord – April 10, 1972 – things get darker for ‘le serpent l’intérieur du tunnel’

It didn’t take long for the underlying wounds to breach the Smithsonian band-aids. By January 1972, most of the currencies had appreciated against the US dollar and were hitting the upper limits of the Smithsonian bands. Renewed speculation that the US dollar was still overvalued mounted and currency traders clearly were forming the view that the Smithsonian Agreement was unsustainable and to keep it on track in the short-term would require huge central bank intervention in the form of US dollar purchases in the foreign exchange markets (BIS, 1972: 32). The Bank of International Settlements (BIS, 1973: 20) referred to the developements in early 1983 “in the rather battered international monetary system may be said to come under the heading of unfinished business left over from the upheaval of 1971. In broader perspective, they constituted a further instalment of the more or less permanent crisis which has prevailed since 1967”.

The Smithsonian Agreement had two major aims: (a) to quickly calm down the foreign exchange markets and stop the massive flow of funds out of the US and into Europe so that the fixed exchange rates could be managed; and (b) to progressively allow the revised exchange rate parities (devalued US dollar and revalued European currencies) to alter trade patterns to allow the US to reduce its balance of payments deficits and nations such as Germany to reduce its massive balance of payments surpluses. The 1973 BIS Annual Report (BIS, 1973: 20) concluded that “the more immediate aim was not achieved, nor were any real signs evident during 1972 of progress towards the longer-term adjustment process”. As we will see, this led to the a renewed crisis in early 1973.

But the Europeans were intent on modifying arrangements in their own eccentric way to reduce the fluctuations in the values of their own currencies. Their devotion to the impossible, given the circumstances, was persistent to say the least. The central bankers of Europe were worried that the plus or minus 2.25 per cent tolerances against the US dollar – the ‘tunnel’ – allowed for under the Smithsonian Agreement were too wide a path for the ‘snake’ to traverse. Remember, that this range of tolerance against the US dollar allowed for much wider fluctuations against each other. For example, one currency might start out at its lower limit (-2.25 per cent against the US dollar) and under the Agreement it could appreciate by 4.5 per cent against the dollar (to the upper limit of allowable fluctations, +2.25 per cent). At the same time, another currency could be at its upper limit and depreciate by 4.5 per cent against the dollar to hit its lower limit. As a consequence, the fluctuation of the first currency against the second could be 9 per cent and still remain within the limits set by the Smithsonian Agreement.

The Smithsonian bands were also at odds with the sentiment expressed in the Werner Report (1970: 26), which had recommended “the elimination of margins of fluctuation in rates of exchange” as the final goal of the economic and monetary union, and, narrowing the fluctuations in the adjustment phase. So while the European Community nations had signed up to the Smithsonian Agreement in December 1971, the Council of the European Community agreed to a deal among themselves in March 1972 that was significantly different to that Agreement. On December 13, 1971, the Committee of Governors of the Central Banks of the Member States established a “group of experts” presided over by M. Théron. Their report, submitted on February 2, 1972 (Théron, 1972), provided the design of what formally became known as the ‘snake in the tunnel’ system. This system represented the first European-specific attempt to maintain fixed exchange rates among European currencies and was the extension of work done previously by an expert group under the direction of Belgian central bank governor, Baron Ansiaux in 1970, which informed the Werner Report. In other words, the ‘snake’ was not a short-term response to the tensions emerging following the signing of the Smithsonian Agreement. In fact, for a very short period in early 1972, foreign exchange markets were calmed and the Europeans thought it was apposite to return to the Werner plan to map out the adjustment phases towards complete economic and monetary union (BIS, 1973).

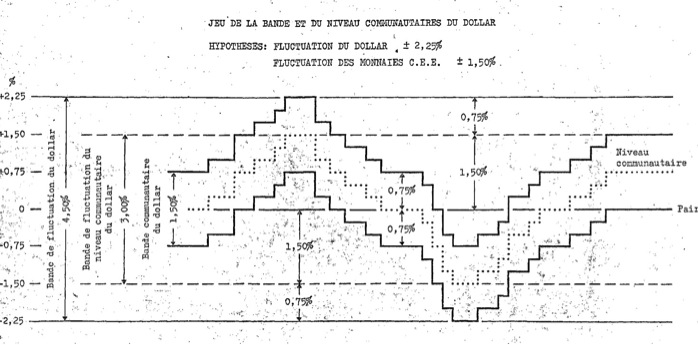

The Théron group of experts recommended that the ‘snake’ (the allowable fluctuations of the European currencies) should be plus or minus 1.5 per cent in a ‘tunnel’ of 4.5 per cent (the fluctuations of these currencies against the US dollar permitted under the Smithsonian Agreement) (see Figure 1.1). The Council of European Community met on March 21, 1972 and resolved to introduce the first coordinated step towards economic and monetary union along the Werner path. After considering the Théron Report, they resolved to gradually reduce the margins for currency fluctuations within Europe, while “fully utilising the margins of fluctuations allowed for by the International Monetary Fund”, that is, the Smithsonian Agreement (“tout en utilisant pleinement les marges de fluctuation admises par le Fonds monétaire international”) (Council of European Community, 1972). The ‘snake in the tunnel’ thus became the first specific element of the otherwise vague Werner implementation process.

Figure 1.1 Le serpent et le tunnel – Théron group of experts, February 1972

Source: European Council (1972) Annexe 2.

The Council Resolution indicated that from July 1, 1972, the fluctuations between currencies of the Member States would not exceed 2.25 per cent, which was a rather skinnier snake than the 3 per cent recommended by the Théron group of experts but still consistent with the hope of returning to largely fixed exchange rates. On April 10, 1972, the Committee of Governors of the Central Banks of the Member States met in Basel to map out the practicalities of the March Council Resolution, which had called on them to act to reduce the margins of currency fluctuations. At that meeting, the central banks of the Member States and those of Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom (the latter three were due to join the EEC in January 1973) agreed to limit the fluctuations between their currencies to plus or minus 2.5 per cent. They retained the Smithsonian band of 4.5 per cent against the US dollar. This agreement became known as the 1972 Basel Accord.

The central bankers agreed to intervene in foreign exchange markets if their currencies were in danger of breaching the new more restricted ‘snake’. To facilitate cooperation in this intervention, they also agreed to various arrangements where they would swap their currencies with each other to ensure that they could actually maintain this commitment. The Basel Accord took effect on April 24, 1972 to take effect two weeks later and is popularly referred to as the ‘snake in the tunnel’. The ‘snake’ is the more restrictive limits agreed by the European partners, while the ‘tunnel’ was the fluctuations against the US dollar permitted under the Smithsonian Agreement.

It soon became obvious that the system was not viable. Facing an election, the US government was running a very expansionary monetary policy (interest rates low) which led to inflationary pressures in Europe and very strong balance of payments surpluses as a result of their higher interest rates attracting massive capital inflows from the US. Early 1973 became 1971 revisited.

THE CRISIS HAS OCCURRED AND TOMORROW WE WILL EXAMINE the FORMAL SNAKE IN THE TUNNEL – THE BASEL AGREEMENT 1972 – AND THE SHENANIGANS THAT FOLLOWED.

THIS IS LEADING TO THE CREATION OF THE EMCF, THE FAILURE OF THE SNAKE, AND STAND-OFFS GALORE!

[TO BE CONTINUED]

[THEN MORE TO FOLLOW – ON THE INITIATIVES LATER IN 1970s DEBATES, DELORS REPORT etc COMING]

Additional references

This list will be progressively compiled.

Bank of International Settlements (1973) Forty-Third Annual Report, Basel.

Council of European Community (1972) Resolution concernant la réalisation par étapes de l’union économique et monétaire dans la Communauté, Journal officiel, No C038, April 18, 1972, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:41972X0418:FR:HTML

Théron, M. (1972) ‘Comité des Gouverneurs des Banques centrales des Etats membres de la Communauté économique européenne, Pre-rapport du Groupe d’experts présidé par M. Théron, 8 janvier 1972’,

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/emu_history/documentation/chapter6/19720108fr10interimreportfluct.pdf

When were capital accounts liberalized? Seems to be where things started to go wrong.

‘Free capital movement’ just means freedom to take on foreign currency loans. How is it expected that central bank can even influence economy by changing interest rates if borrowers can take on FX-loans with interest rates set by foreign central bank? Seems to defeat whole point.

Capital account liberalization is driven by this fantasy that ‘capital’ i.e. stuff from which to make loans, is scarce resource.