Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – July 6, 2013 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

In recent days, yields on Portugal government bonds have risen sharply and have once again raised the issue that Eurozone governments face insolvency risk. If, for example, Portugal was to leave the Eurozone and in re-establishing its own floating currency, it re-denominated all euro liabilities into this new currency, then they would eliminate that risk on all future liabilities.

The answer is False.

This question focuses on whether the floating own currency is a sufficient condition for fiscal policy independence. The answer is that it is not.

The answer would be true if the sentence had added (on all future liabilities) … in its own currency. The national government can always service its debts so long as these are denominated in domestic currency.

The answer is false because there is a possibility that the government may borrow in foreign currencies in addition to its own currency.

It also makes no significant difference for solvency whether the debt is held domestically or by foreign holders because it is serviced in the same manner in either case – by crediting bank accounts.

The situation changes when the government issues debt in a foreign-currency. Given it does not issue that currency then it is in the same situation as a private holder of foreign-currency denominated debt.

Private sector debt obligations have to be serviced out of income, asset sales, or by further borrowing. This is why long-term servicing is enhanced by productive investments and by keeping the interest rate below the overall growth rate.

Private sector debts are always subject to default risk – and should they be used to fund unwise investments, or if the interest rate is too high, private bankruptcies are the “market solution”.

Only if the domestic government intervenes to take on the private sector debts does this then become a government problem. Again, however, so long as the debts are in domestic currency (and even if they are not, government can impose this condition before it takes over private debts), government can always service all domestic currency debt.

The solvency risk the private sector faces on all debt is inherited by the national government if it takes on foreign-currency denominated debt. In those circumstances it must have foreign exchange reserves to allow it to make the necessary repayments to the creditors. In times when the economy is strong and foreigners are demanding the exports of the nation, then getting access to foreign reserves is not an issue.

But when the external sector weakens the economy may find it hard accumulating foreign currency reserves and once it exhausts its stock, the risk of national government insolvency becomes real.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Modern monetary theory in an open economy

- Debt is not debt

- The deficit and debt debate

- Debt and deficits again!

Question 2:

Norway has accumulated one of the largest sovereign funds as a result of its North Sea energy endowments, which have allowed it to maintain high standards of living and still run budget surpluses. Once the resource wealth dissipates and Norway’s external sector moves into deficit, the sovereign fund accumulation will have created more space for non-inflationary spending.

The answer is False.

The public finances of a country such as Norway – which issues its own currency and floats it on foreign exchange markets are not reliant at all on the dynamics of its industrial structure. To think otherwise reveals a basis misunderstanding which is sourced in the notion that such a government has to raise revenue before it can spend.

So it is often considered that a mining boom which drives strong growth in national income and generates considerable growth in tax revenue is a boost for the government and provides them with “savings” that can be stored away and used for the future when economic growth was not strong. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows:

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending capacity is independent of taxation revenue. The non-government sector cannot pay taxes until the government has spent.

- Government spending capacity is independent of borrowing which the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about “crowding out”.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

These principles apply to all sovereign, currency-issuing governments irrespective of industry structure. Industry structure is important for some things (crucially so) but not in delineating “public finance regimes”.

The mistake lies in thinking that such a government is revenue-constrained and that a booming mining sector delivers more revenue and thus gives the government more spending capacity. Nothing could be further from the truth irrespective of the rhetoric that politicians use to relate their fiscal decisions to us and/or the institutional arrangements that they have put in place which make it look as if they are raising money to re-spend it! These things are veils to disguise the true capacity of a sovereign government in a fiat monetary system.

In the midst of the nonsensical intergenerational (ageing population) debate, which is being used by conservatives all around the world as a political tool to justify moving to budget surpluses, the notion arises that governments will not be able to honour their liabilities to pensions, health etc unless drastic action is taken.

Hence the hype and spin moved into overdrive to tell us how the establishment of sovereign funds. The financial markets love the creation of sovereign funds because they know there will be more largesse for them to speculate with at the expense of public spending. Corporate welfare is always attractive to the top end of town while they draft reports and lobby governments to get rid of the Welfare state, by which they mean the pitiful amounts we provide to sustain at minimal levels the most disadvantaged among us.

Anyway, the claim is that the creation of these sovereign funds create the fiscal room to fund the so-called future liabilities. Clearly this is nonsense. A sovereign government’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained. So it would always be able to fund the pension liabilities, for example, when they arose without compromising its other spending ambitions.

The creation of sovereign funds basically involve the government becoming a financial asset speculator. So national governments start gambling in the World’s bourses usually at the same time as millions of their citizens do not have enough work.

The logic surrounding sovereign funds is also blurred. If one was to challenge a government which was building a sovereign fund but still had unmet social need (and perhaps persistent labour underutilisation) the conservative reaction would be that there was no fiscal room to do any more than they are doing. Yet when they create the sovereign fund the government spends in the form of purchases of financial assets.

So we have a situation where the elected national government prefers to buy financial assets instead of buying all the labour that is left idle by the private market. They prefer to hold bits of paper than putting all this labour to work to develop communities and restore our natural environment.

An understanding of modern monetary theory will tell you that all the efforts to create sovereign funds are totally unnecessary. Whether the fund gained or lost makes no fundamental difference to the underlying capacity of the national government to fund all of its future liabilities.

A sovereign government’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing. Therefore the creation of a sovereign fund in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations. In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system.

The misconception that “public saving” is required to fund future public expenditure is often rehearsed in the financial media.

First, running budget surpluses does not create national savings. There is no meaning that can be applied to a sovereign government “saving its own currency”. It is one of those whacko mainstream macroeconomics ideas that appear to be intuitive but have no application to a fiat currency system.

In rejecting the notion that public surpluses create a cache of money that can be spent later we note that governments spend by crediting bank accounts. There is no revenue constraint. Government cheques don’t bounce! Additionally, taxation consists of debiting an account at an RBA member bank. The funds debited are “accounted for” but don’t actually “go anywhere” and “accumulate”.

The concept of pre-funding future liabilities does apply to fixed exchange rate regimes, as sufficient reserves must be held to facilitate guaranteed conversion features of the currency. It also applies to non-government users of a currency. Their ability to spend is a function of their revenues and reserves of that currency.

So at the heart of all this nonsense is the false analogy neo-liberals draw between private household budgets and the government budget. Households, the users of the currency, must finance their spending prior to the fact. However, government, as the issuer of the currency, must spend first (credit private bank accounts) before it can subsequently tax (debit private accounts). Government spending is the source of the funds the private sector requires to pay its taxes and to net save and is not inherently revenue constrained.

You might have thought the answer was maybe because it would depend on whether the economy was already at full employment and what the desired saving plans of the private domestic sector was. In the absence of the statement about creating more fiscal space in the future, maybe would have been the best answer.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A mining boom will not reduce the need for public deficits

- The Futures Fund scandal

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

Question 3:

If a nation is running a current account deficit accompanied by a government sector surplus of equal proportion to GDP, the private domestic sector must to be in deficit.

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

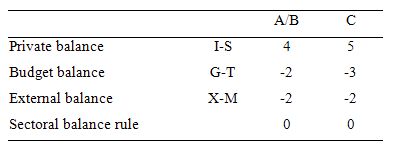

The following Table represents the three options in percent of GDP terms. To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

The first two possibilities we might call A and B:

A: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending less than they are earn

B: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

So Option A says the private domestic sector is saving overall, whereas Option B say the private domestic sector is dis-saving (and going into increasing indebtedness). These options are captured in the first column of the Table. So the arithmetic example depicts an external sector deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and an offsetting budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP.

You can see that the private sector balance is positive (that is, the sector is spending more than they are earning – Investment is greater than Saving – and has to be equal to 4 per cent of GDP.

Given that the only proposition that can be true is:

B: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

Column 2 in the Table captures Option C:

C: A nation can run a current account deficit with a government sector surplus that is larger, while the private domestic sector is spending less than they are earning.

So the current account deficit is equal to 2 per cent of GDP while the surplus is now larger at 3 per cent of GDP. You can see that the private domestic deficit rises to 5 per cent of GDP to satisfy the accounting rule that the balances sum to zero.

The final option available is:

D: None of the above are possible as they all defy the sectoral balances accounting identity.

It cannot be true because as the Table data shows the rule that the sectoral balances add to zero because they are an accounting identity is satisfied in both cases.

So what is the economic rationale for this result?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real costs and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Regarding the answer to question #2 about sovereign wealth funds (which I actually got right this time)- are there any ways for a nation that issues fiat currency to “save as a nation”? I mean just suppose there really was going to be an extreme shortage of labor available in 20 years for whatever reason. Is there anything a nation could do now to mitigate that? I ask because I had made some comments on Jim Hamiltons Econbrowser post http://www.econbrowser.com/archives/2013/07/offbalancesheet_1.html questioning his idea that we should be ” saving as a nation” right now. Somehow I think that my ideas for saving as a nation are not what most people who are pushing this idea right now are at all interested in.

One more question- economists often say that savings equals investment. What is an MMT perspective on that? Is it true and if so are savings a prerequisite for investment? From my reading of your blogs I would say that it isnt necessarily true or that at the very least, investment can take place in the absence of savings. Maybe the investment creates savings?

Dear Bill

My understanding of a sovereign fund like Norway’s is that its purpose is to avoid the Dutch disease. If Norway were to spend all of its oil profits, its currency would appreciate a lot, and that would kill a lot of other industries in the tradable sector. By setting up a sovereign fund, the Norwegians live below their means, but they avoid the dislocations that would have occurred if they had used all the oil profits for consumption. By choosing to live below their means now, the Norwegians can live above their means at some time in the future when they start liquidating their sovereign fund. I’m not talking about the government here, but about the country as a whole. Countries that run a big current account surplus, as Norway does, live below their means, don’t they? And if they live below their means in the present, then they can live above their means at some future time, unless their assets are devalued to the point of nothingness.

Regards. James

James, I have the same questions. But, this is what I am thinking-I dont know if Norway sells its oil for US$ but if they did and even if they spent all those dollars buying things for sale in US dollars right away I dont know how that would drive the price of its own currency up. And while an individual can live below his means and save now for future consumption with a really good chance of realizing that increased future consumption, can an entire country do that? I mean how would Norway enforce some other country’s obligation to pay up so to speak? I am assuming Norway is buying foreign assets of course. If they are buying Norwegian assets I’m not sure it works at all.

I mean that, in the future, a country is going to be able to produce a finite amount of goods and services for consumption using the resources that are available at that time right? So unless this “national savings” or sovereign wealth fund increases the amount or quality of those resources that will be available, I dont understand how it would work.

Dear Jerry Brown

Let’s suppose that I lend you 20,000 and that 10 years from now you have to pay me back 30,000. What has happened? I have transferred 20,000 in purchasing power to you in the present in return for a transfer of purchasing power from you to me 10 years from now. That’s what a loan is, an exchange of current purchasing power in return for a higher future purchasing power. However, the future purchasing power is only a claim. A creditor has only a claim on the debtor. The claim may turn out to be worthless. A creditor does not transfer financial resources from the present to the future, as so many people believe.

Now let’s suppose that Norway sells a million barrels of oil for 80 dollars. It cost Norway, say, 30 dollars to produce a barrel. It has therefore 50 million dollars of profits. It uses those 50 million to purchase shares in a Brazilian company. The Brazilians can now use the 50 million to import goods. 20 years from now, Norway sells those shares for 75 million. It can now use those 75 million to import stuff.

Let’s assume that, without oil, Norway exports and imports 50 billion. Let’s further assume that Norway has 40 billion in oil profits. If it didn’t invest those 40 billion abroad, but used them, say, to cut taxes by 40 billion, then there would now be an excess supply of 40 billion dollars in Norway. That would drive the price of dollars down in terms of the Norwegian currency, so the Norwegian currency would rise. At the new exchange rate, Norway might import 70 billion and export 30 billion other than oil.

Without the sovereign fund, Norway will export 30 billion in non-oil and import 70 billion and have balanced trade. With the sovereign fund, Norway will export 50 billion in non-oil and also import 50 billion and have a current account surplus of 40 billion.

Cheers. James

Dear James Schipper, (sorry for the previous lapse in formality)

I am not pretending to be an expert in this which is why I am also asking questions. It does seem reasonable to me that if Norway was able to invest now in future foreign output and also have a good chance of collecting on that future foreign output then that kind of plan would work. Collecting may not always be possible you know.

I think the key question is are you assured of future real goods and services, not some future income stream that may or may not be able to purchase those goods and services.

Do sovereign funds allow inter-generational transfers in terms of adjusting currency exchange rates? Norway has to do something with the oil money. If all the USD from oil sales were converted into Norwegian currency to sit in Norway bank accounts, the exchange rate would be nuts. Perhaps after the oil has run out, the sovereign fund could be sold down to help pay for imports.

Lets imagine Norway split into two countries because half the country wanted a sovereign fund and the other half wanted to simply give the oil away. In fifty years time all of the oil has run out and energy needs to be imported. I’d be surprised if having a sovereign fund that could be sold down didn’t help to keep such imports affordable and prevent a big drop in the currency exchange rate. My guess is that the half of the country that had the sovereign fund might be able to buy in raw materials or whatever to keep the lights on and perhaps be more prosperous.

Of course it only makes any sense at all to have a sovereign fund if all useful real spending has been done. It is vastly more important to have optimal education and expertise of the population. Perhaps it would be better to spend the sovereign fund on developing futuristic technologies than on bidding up share prices. I guess the massive problem is that the Norway government does not have the expertise to know what technology projects would be good to fund.

I wonder what would happen if Norway (or other oil states such as UAE) tried to say donate sewerage and clean water supply infrastructure to every city across the world that does not currently have them. If the Norwegian government paid companies to install such infrastructure as a gift, perhaps Norwegian people would gain expertise at running vast infrastructure projects and so develop an expertise that would continue to be drawn upon even after the oil ran out. Perhaps in 2060, long after oil had run out, whenever a city needed new water works, a Norwegian firm would be employed????

IMHO, the Norway question shows the difficulty of making up complicated but brief multiple choice questions, especially in the international environment of the intertubes.

How “will have created more space for non-inflationary spending” and other parts are interpreted can change the True/False answer. The test should really ask for essays. 😉

To think otherwise reveals a basis misunderstanding which is sourced in the notion that such a government has to raise revenue before it can spend. Norway does not have to raise revenue before it can spend Kroner. It certainly does have to raise dollars somehow before it can spend dollars, and spending in dollars can disinflate the Norwegian currency at any time.

(Norwegian) Arno Mong Daastøl’s The Petroleum Fund and the LO passiveness covers debates between him, Michael Hudson and Norwegian billionaire Øystein Stray Spetalen versus numbskull Norwegian trade union and government “economists” & politicians, including the PM of Norway. (See http://www.arno.daastol.com/articles.html#Publishedpopulararticles for more such, some with English translation.)

Hudson:Believe Norway Wastes Oil Money (google translation)

and a full length Levy Working Paper:

What Does Norway Get Out of its Oil Fund, if Not More Strategic Infrastructure Investment?

See also Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Risk Vortex and Norway’s Oil Fund: Is it Realizing its Full Potential?.

Note how precarious such “sovereign wealth funds” can be: Daastøl: “Almost any degree of risk of loss and unprofitability on projects in infrastructure cannot possibly be worse than the oil fund’s losses of 800 billion during the recent financial crash”

James Schipper: If it didn’t invest those 40 billion abroad, but used them, say, to cut taxes by 40 billion, then there would now be an excess supply of 40 billion dollars in Norway. Norway doesn’t levy taxes in dollars, and Norwegians don’t pay their bills in dollars. However it raises or cuts its kronor taxes, doesn’t immediately change the supply of dollars held in Norway. I am sure any Norwegian – or myself – would be happy to patriotically use their share of an excess $40B to buy dollar priced imports. The whole point is what will it do with its oil dollars. The modern Norwegian government answer is: Put it on Red, not Black or Buy High, Sell Low, but above all, don’t let any Norwegian-held wealth into Norway. 🙂 The MMT/Hudson/ Daastol/Spetalet-traditional Norwegian answer is – integrate the purchases into a national economic plan instead of gambling abroad. Importing furrin stuff with the pile of dollars you already have is not Dutch-Diseasy inflationary but the opposite. (The main contenders for world’s best economic theory are MMT & “Always Total Opposite of the Mainstream” Theory – ATOM theory. Not sure which is better. 🙂 )

Unfortunately, weird accounting conventions, beliefs and practices perpetrated by numbskulls in (very) high places in Norway and elsewhere (See this gang of eight thread: Norway’s PM: “Michael Hudson is totally wrong .) obscure the extremely simple truths which Bill here tries to pound in again. Norway don’t need nobody else to make Norwegian kroner.

SomeGuy, I guess what Norway might be really scared of (and perhaps with reason) is of all Norwegian people taking up a lottery winner style lifestyle, employing foreigners to do all work and losing all expertise and self reliance before the oil runs out (as perhaps happens in the UAE?). In principle I total agree that bidding up the price of the global stock market seems inane but in practice Norwegian people seem to have fared better than pretty much any other population that lives in an oil state. To some extent oil is a curse and yet Norway has a contented prosperous population that will probably be well suited to living without oil when the oil runs out. Like I said it seems odd that something sensible can’t be thought of to do with the money (such as donating infrastructure development to third world) BUT perhaps that would simply mire Norway in grief and conflict if corruption etc derailed such hypothetical projects. To be honest some things that Norway does spend money on actually seem VERY destructive eg Norway is at the forefront of the appalling monstrosity that is salmon farming. It sucks up ten tonnes of perfect sea fish from west africa (rendering local subsistence fishing communities destitute) to use as feed pellets to make each tonne of chemically treated unhealthy disease ridden farmed salmon. I’d rather have oil money pissed away on buy high sell low stock market nonsense than driving real destruction such as salmon farming. The Japanese approach of encasing beaches and rivers in concrete as some boondoggle “infrastructure” pretext for spending seems similar.

Some Guy, I just read the Michael Hudson Levy working paper you linked to- thanks.

To be honest it seemed very shaky to me as to what Norway SHOULD do with the oil money. He does not like citizens dividends (as in Alaska) and seems not to trust the public to spend money wisely. He says education, transport and science need to be be developed. I agree that the selling off of silicon mines to the Chinese does seem bizarre though as that might be one thing that Norway could benefit from when the oil runs out. I’ve wondered before whether that is part of some convoluted ploy on the part of the Chinese to try and shift the effects of all the USD purchases by China. Previously China bought USD so as to try and stabilize exchange rates. Inadvertently that caused China to fund US military expansion. Instead China buys Norwegian silicon mines. Norway uses the money China paid for the mines to buy US stocks and so indirectly supports the USD/Yuan echange rate. China sells the silicon at a loss to the US solar industry. In that way China maintains a stable USD/Yuan exchange rate (so facilitating trade) and instead of funding US military adventurism funds solar power development????

My impression was that in Norway everyone already gets as much education and science funding as they can stomach? Not everyone has the inclination to be a scientist. Digging road and railway tunnels might help in the future I guess but perhaps more than they currently have might just amount to environmental destruction. I don’t think Michael Hudson faces up to the reality that Norway and AbuDhabi have massive amounts of oil revenue for a small population and Norway is already very highly developed.

Dear Some Guy

The purpose of a sovereign fund is not to avoid inflation. If Norway were to use all its oil profits to import goods and services, the krona would appreciate a lot. If anything, that would be deflationary. The result of such a major increase in the value of the krona would be that Norway would be flooded with imports and Norwegian import-competing industries would go bankrupt on a large scale. As consumers, Norwegians would benefit, but a lot of their producers would be badly hit. It would bring about serious dislocations within Norway. If there were 45 million Norwegians instead of 4.5, the situation would be different. Norway is not Saudi Arabia, where they never had industry to speak of.

……………………………non-oil exports…..oil exports……..imports…….trade surplus

no oil…………………………..50………………….00……………..50…………….00

oil with sovereign fund……..50………………….40……………..50…………….40

oil without sovereign fund…30………………….40……………..70…………….00

These figures aren’t data but meant to illustrate what roughly the function of the sovereign fund is. It is prevent a decline in the non-oil tradable sector.

Regards. James