The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Differences on the Eurozone periphery

This will be one of those blogs that lays out what a researcher does in a day as opposed from the blogs I write that use what I do in a day as an evidence base for advocacy. The former type of blog is based on data digging and observing some interesting patterns. In the current context, the “digging” is not finished and so the story presented is incomplete. But if you have a penchant for statistics and data patterns like me, then you will find the following story interesting. This work is part of a larger work I am pursuing that considers the question of cyclical labour market adjustments. That will become a completed book in a few years (there are others in the queue ahead). But today I was examining the relative responses of real GDP and employment over the course of the economic cycle and some interesting patterns certainly emerged. What we find, among other things, is that the Eurozone nations on the periphery have behaved quite differently to each other over the crisis (and prior to the collapse).

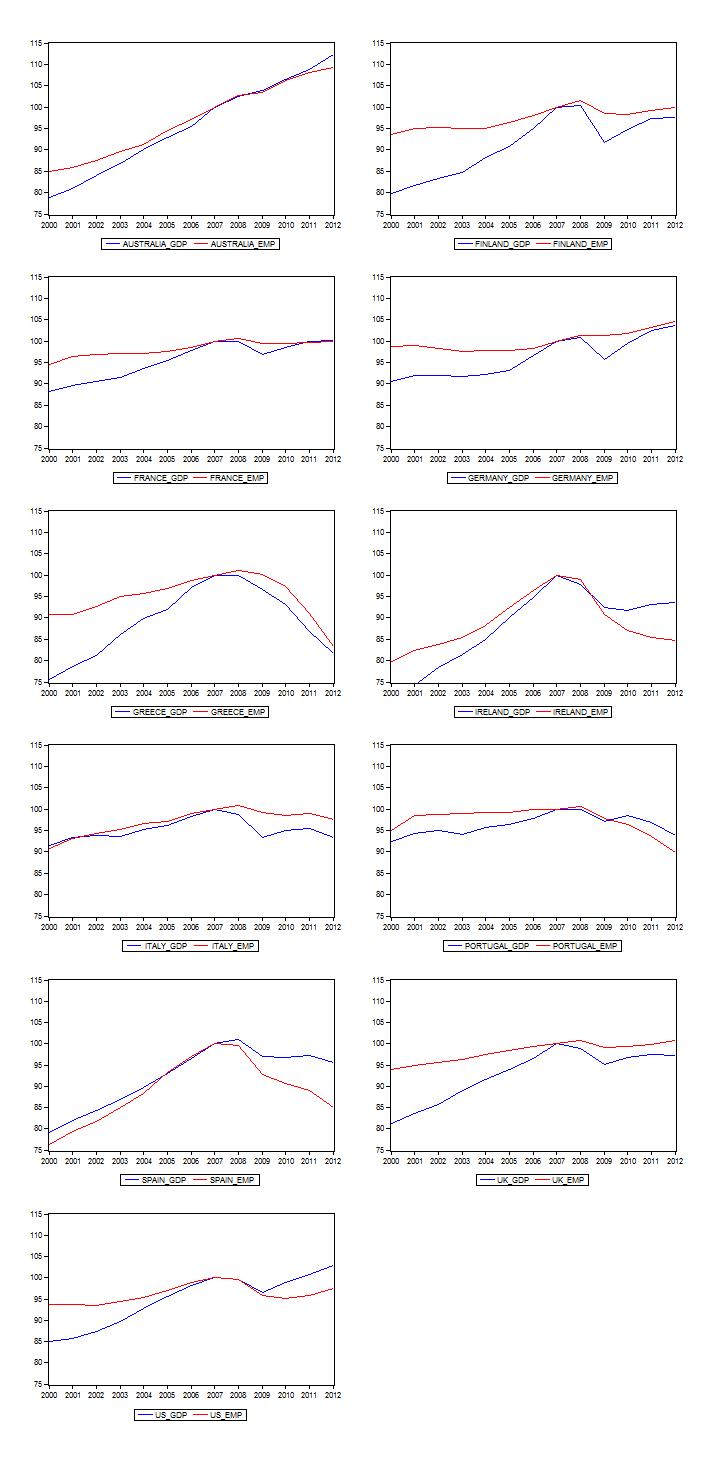

Consider the following graph (which is in fact a series of graphs). They use the IMF annual – World Economic Outlook – database (most recent release October 2012) and show real GDP and total employment (indexed to 100 at 2007). The peak of the previous economic cycle varied across the sample with some peaking in 2008. But the choice of 2007 as the index base doesn’t alter the story at all.

Real GDP is blue and employment is red. I created a common vertical axis scale on all graphs to allow readers a chance to better appreciate the amplitude of the recession impacts in each nation. In effect, Australia distorts the sample (if I excluded Australia then the maximum value of 105 on the indexes would have contained all the other nations adequately).

While there is a lot to talk about in these graphs, several things really stand out, which require further discussion.

First, Australia is in a world of its own in this sample of Eurozone (foreign currency users) and major currency using nations. I could have included other nations but the graph would have become too large and essentially not a lot would have been added at this stage.

Australia avoided the recession (officially) despite experiencing a slowdown because it introduced a major fiscal stimulus in late 2008 and early 2009, centred on cash handouts (in the first of the packages) and then public infrastructure spending (second package). This intervention allowed key sectors, which normally crash in a downturn (such as construction) to continue growing.

Second, several nations experienced increasing labour productivity (measured in persons employed) in the lead up to the crisis – employment index growing more slowly than the real output index. Only Italy, Spain and Portugal did not enjoy this status.

Third, excluding Australia, there are three broad behaviours after the crisis hit. For Finland, France, Germany, Italy (to some extent), the UK, and at a push, the US, real GDP fell sharply but the employment decline was less severe (and for Germany didn’t happen).

For Greece, both the real GDP and the employment collapse has been very severe. The real GDP index from 2007 to 2011 fell from 100 to 81.6 while the employment index fell from 100 to 83.2. That means the Greek economy (and its labour market) has contracted by nearly a 20 per cent so far and there is no end in sight to that decline.

The so-called bailout agreement sealed earlier this week will not help and already it is clear that the Greek economy will continue to unravel despite the drivel from the Government about it being a new dawn, a new day, a new beginning for the nation. I will write about that problems with that package another day.

Then we have Ireland and Spain as the third distinctive grouping. Relative to Greece, the collapse in real GDP has not been as severe for these two nations. The real GDP index fell from 100 in 2007 to 95.7 for Spain and 93.5 for Ireland. A substantial contraction to be sure (and no end in sight) but much less severe when compared to the near 20 per cent contraction in the size of the Greek economy.

But in terms of employment, the behaviour depicted in the three nations is similar. The employment index fell from 100 in 2007 to 83.2 for Greece (2011), 85 for Spain, and 84.6 for Ireland. So roughly between 16 per cent and 18 per cent contraction in the labour market, which is a huge collapse by any measure.

So why has employment fell so much in Spain and Ireland when the overall contraction in the economy was smaller than it was for Greece? Researchers love these sort of puzzles.

In this case, the answer is not very far away though.

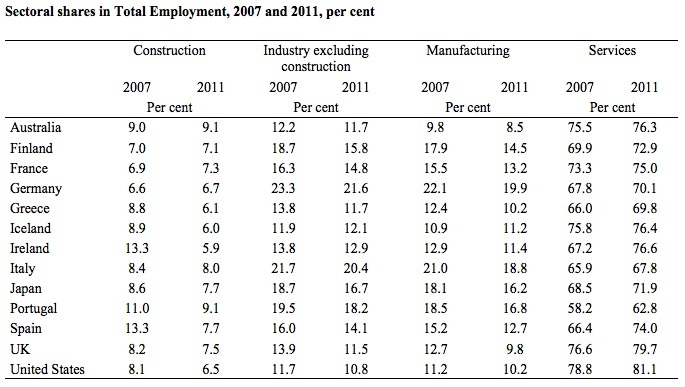

The next Table is constructed using OECD Short-Term Labour Market Statistics – quarterly employment by industry data. The table presents the annualised proportion of employment by broad sector – Construction, Industry excluding construction, Manufacturing and Services – in total employment for 2007 and 2011 (per cent).

A striking result is that for Spain and Ireland, the growth in the construction sector associated with their real estate bubbles was significant. In Ireland’ case, the relative importance of the construction sector rose in the years leading up to the crisis. It was around 12.6 per cent of total employment in 2005 and rose to a peak of around 14 per cent in 2007 and then collapsed to 5.9 per cent of total employment by 2011. In the case of Spain, the relative growth of the construction sector was similar, going from 12.4 per cent in 2005 to a peak of around 13.3 per cent in 2007 and then collapsing to 7.7 per cent of total employment by 2011.

That behaviour sets these two nations apart and helps explain why the collapse in employment has been so severe. It is likely that if the respective governments had have intervened early in the crisis and sustained employment growth (via fiscal stimulus) then the private debt insolvencies would not have been a severe and the real estate boom would have come to a less severe end.

The spectacular rise of the construction sector in the period leading up to the crisis in Spain and Ireland also highlights the gross lack of oversight that their respective governments had on the financial sector.

Construction is typically a highly pro-cyclical industry and is one of the leading indicators of where the economic cycle is heading. That is, it starts to contract before the other sectors in the economy start to go into the slowdown. This is because housing starts fall and business investment in buildings contracts before the rest of the economy contracts.

So Spain and Ireland were very exposed by the ridiculous absolute and relative growth in its construction sectors prior to the crisis.

The collapse of the construction sectors in Spain and Ireland is also to be compared to what happened in Australia, where a similar real estate boom was experienced in the period leading up to the crisis, although our property bubble was already slowing by 2004-05.

As noted above, the construction sector in Australia started to contract in early 2008 consistent with the impending recessionary forces. But the fiscal stimulus, targetting large public infrastructure projects stopped that normal behaviour and was a significant factor in warding off a recession in Australia.

No such opportunities were given to the Spanish and Irish construction sector given that the EU elites forced austerity on to the ailing economies. Things would have been much less severe had the Troika not formed and had the EU disregarded their contractionary-biased Stability and Growth Pact fiscal rules.

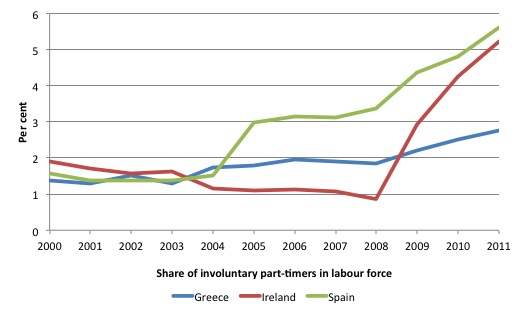

The following graph shows the OECD measure of underemployment (share of involuntary part-timers in labour force) for Greece, Ireland and Spain from 2000 to 2011. Spain stands out. It has been one of the few European nations to follow the Anglo trend in casualising its labour market.

Related data from the OECD, which I haven’t time to publish today, shows that this increased underemployment in Spain in the period leading up to the crisis was accompanied by a significant shift in the way the labour market was organised.

Spanish workers are increasingly forced to work under temporary contracts (some 32 per cent of total employment by 2007 according to the OECD data). For Greece the corresponding proportion was around 10 per cent.

These temporary contracts have made it easier for Spanish firms to reduce their workforces. So for other Europe as a whole, firms sought other labour market adjustment options (shorter-hours, shorter-weeks) as well as shedding employment. But for Spain, it was easier for firms to adjust to the contraction in aggregate demand by sacking workers.

The data shows that the bulk of the job losses between 2007 and 2012 have been endured by temporary workers in Spain. So not only were Spanish workers becoming increasingly disadvantaged in the growth period prior to the collapse but once the economy moved into recession their lack of job security meant they were in the front-line of the contraction. A double-whammy.

The trend to increased underemployment and rising casualisation in Ireland is post-crisis and in that sense the comparison between Ireland and Spain, pre-crisis does not hold. But what it means is that Irish workers (and workers generally) are being disproportionately forced to endure the costs of the recession and the failed government policies.

Conclusion

In all recessions, it is the lower ends of the labour market – the precarious workers with low pay and less skill – that bear the brunt of the adjustment. That is not any different this time around.

Usually, the losses in the downturn given way to a return to previously held working conditions when the economy returns to growth. So while the losses in the downturn in the form of unemployment and the accompanying lost income are permanent, the workers get back on track once employment growth resumes.

However, the imposition of fiscal austerity in many nations in the current crisis will ensure not only that the current losses are enormous but that the working conditions previously enjoyed will be lost forever. Years (decades) of hard-won gains by the workers are evaporating in the cause of austerity.

There is no surprise. The neo-liberals have used the prolonged crisis to re-assert their program of wealth and income transference to the elites and to put the last nail in the welfare state coffin. That is their agenda and all the financial gobbledegook – about impending insolvency and bond market revolts – is just a smokescreen for their more venal ambitions.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

In Spain and Ireland, there was massive overconstruction before 2008, which means that there was also overemployment in the construction sector. These people had to be transfered to other sectors sooner or later because there is no point in employing people to build houses which aren’t needed. Both countries made the mistake of importing lots of immigrants during the bubble. When you import immigrants during a boom, they will still be there when the boom collapses. Imigrants need a place to live in too, which means that some of the houses built were needed only because of the arrival of immigrants. They were demographic investments, that is, capital-widening rather than capital-deepening. There was a vicious cycle here. The booming construction sector induced the import of immigrants, who in turn reinforced the boom by creating additional demand for houses.

Regards. James

@Bill

I follow diesel consumption very closely in Euro countries as it can tell you so much about the real levels of activity

Something very profound is happening in Italy.

Perhaps a collapse in construction !

There is a ongoing dramatic terminal dive in diesel consumption since the start of the year.

The IEA remains strangely quiet about the Italian situation….just giving the numbers in passing as if it were a small economy.

It talks about declines in Germany and the UK (now only 1.5 MBD) but nothing about Italy which was at least at one time a big economy.(bigger then the UK)

http://omrpublic.iea.org/demandarchres.asp?demandarch=2012&Submit2=Submit

Italian diesel (work) demand continues its dramatic terminal dive.

omrpublic.iea.org/demand/it_dl_ov.pdf

Could it be…..the worst large country com. vehicle sales by far. (Greece & Portugal are even worse)

http://www.acea.be/images/uploads/files/20121127_PRCV-1210-FINAL.pdf

Italian commercial vehicle sales Jan – Oct

Vans -33.4%

Heavy trucks -28.8%

Trucks – 29.6 %

Buses – 30.8%

French diesel demand now looks like its beginning the decent phase

http://omrpublic.iea.org/demand/fr_dl_ov.pdf

The rise of French construction is mainly a result of rail & tram projects.

Whats happening in Tours (old Money ?) is very interesting.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=33YcVHnRQjM

This area is on the route of the new Tours tram , I imagine its land value has gone up.

fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanitas

They may be pressure from the lower middle class to push out the now former working class from these districts

This development (also on the line) just south of the river and city center seems to have some bank backing

http://www.panoramio.com/photo/62223721

http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deux-Lions

Also this new development to the north.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zl6bfB6Gmt4

It all looks a bit Soviet but we could be seeing something quite profound in city settlement patterns of the future.

This is an interesting set of graphs but it is not clear what is meant by employment exactly. Is it the number of people listed as employed or is it weighted at all according to hours worked?

A related question is to do with productivity. There has been much discussion about productivity in Australia recently where people are complaining about the fall in productivity. On the face of it, the graph for Australia above shows that the productivity as been fairly steady, increasing lately.

Dear Bill,

I think Box I from a recent ECB paper on the Euro labour market complements the above very nicely. ECB staff made a simple regression in order to calculate Okun law coefficients per GDP component (instead of an aggregate number). The results are that consumption elasticity is an order of magnitudate larger than other GDP components. As a result, countries such as Germany which experienced a large drop in exports but not of consumption display only small and temporary loss of employment. Periphery countries which exhibited large credit flows and serious drops on consumption experienced much larger losses of employment.

Since the loss of exports was considered a temporary, exogenous shock, core country companies adapted production through work-hours changes. In the case of periphery countries, loss of output was considered more structural and permanent which led to higher outright loss of employees.

http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp138.pdf

As always, Bill, a very interesting blog. I am in awe of your ability to generate so many interesting insights.

You said “Second, several nations experienced increasing labour productivity (measured in persons employed) in the lead up to the crisis – employment index growing more slowly than the real output index.”

which got me to wondering what exactly was happening in the U.S. The intuitive sense of what it means to increase productivity has to do with “producing more with less human effort”, but of course the economic definition is more like “producing more with lower labor costs”. So I suspect that the “productivity improvements” in the U.S. and other developed countries are largely attributable to shipping jobs off to wherever the labor costs are lower and less due to the effects of real improvements of technology or methodology or training. Is there data available somewhere to test that hypothesis?

Bill,

Whay does your analysis imply for a job guarantee programme in the respective countries? A major exercise in Greece Ireland and Spain and thus less likely to occur?

The Australian real estate bubble has I think been different to Ireland and Spain in that there does not appear to have been a massive boom in over-building. Most of the money has gone into bidding up the price of existing housing, due in part to very generous government incentives for ordinary people to speculate in real estate. Australian investors/speculators have shown almost no interest in building investment properties and instead purchase mainly established dwellings.

We now have a ludicrous situation whereby the main demograph that traditionally drives new detatched home construction – young families – are often locked out by the onerous cost of buying land and building a house (much of it is in the cost of the land itself) while upgraders and investors who have pre-existing leverage available to use continue horse-trading established houses.

The demand for new housing that is actually backed by the ability to pay for it – even at todays low interest rates – continues to slump, but the price does not fall by any significant amount.

That this market is clearly dysfunctional in the extreme would be comical if it were not for the fact that we are not talking about whether or not the next generation can reasonabley and realistically afford the latest digital surround-sound home theatre or something such – we are talking about affordablity of the basic human need for shelter from the elements.

It is yet another example of something that may be percived as being good for the individual (investor or upgrader) creating poor and unfair oucomes and unwinding social progress when veiwed in aggregate.

Paul Krueger,

My understanding is different to yours. The technical definition of productivity, as expressed earlier in these blogs, is the ratio of GDP to hours worked, that is to human effort rather than to labour costs.

To some people, especially those running a business, the ratio of output to labour costs might be more intuitive. Some people talk of “factor productivity”, which I don’t understand at all. Its definition seems to be very vague.

Australia:

The Australian stimulus was awesome in its style. Giving cash to people before they felt the real shock of job losses helped maintain a healthy consumer sector. What happens next for Australia is confusing as the Automatic Stabilizer of a floating exchange rate does not seem to be working and the Australian Gov is hell bent on cutting back spending at the same time as our non mining sector is still hollowed out after making way for the mining boom. Large scale dwelling construction of units (condos) or detached houses cant be financed right now. To help me understand what happens next I am trying to find Graphs on the following:

1. GDP Gap

2.Trend line Productivity Growth (GDP Growth may be a proxy?)

3. Credit Creation Trends

4. Long Term debt cycle

5. Short term debt cycle

6. Debt to disposable income

7. Net worth of households

8. Unemployment rates

I don’t have the skills to convert data from Australian Bureau of Statistics. I can get some info from the RBA Charts site and Keen has some info. However a site that updates this sort of info in Graph would be great.

Can anyone suggest something to help?

Cheers Punchy

Tony,

Productivity for a country as a whole can be the ratio of GDP to hours worked, but how is the movement of jobs off shore reflected in that number? All other things being equal, the hours worked within the country are reduced and the GDP is reduced by the cost of the imported labor. Since the imported labor is cheaper than the domestic labor the ratio would increase (i.e. this would result in a reported increase in productivity). So my point is the same: moving jobs out of developed countries results in a perceived increase in productivity that does not accurately reflect the actual labor content of the goods produced.

When an individual company talks about its productivity, my experience is that they typically measure what is important to them, which is a ratio of revenue to labor cost where once again, movement of jobs to lower cost countries results in a reported productivity increase. In many companies productivity measures also go up when people on fixed salaries are expected to work unpaid overtime.

In either case this makes productivity measures sensitive to labor costs and the real effects of technical/procedural/training improvements on labor hours are diluted or lost in the measure. I suppose what I’m wondering is whether there is (or should be) a way to measure REAL productivity in a way that is not distorted by labor costs.

Irish 2011 transport omnibus was published.

http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/transport/2011/transport11.pdf

The highlight of course continues to be the massive collapse of road freight (biggest fall in Europe by a wide margin)

Y2007 Tonnes carried (thousand) : 299 ,307

Y2011 Tonnes carried (thousand) : 110 ,260

A older transport omnibus gives road freight as 314,826 in 2007 ?

In that 2007 publication 159,865 was road and building site work

In 2011 30,981

However all activities are down hugely ( delivery of goods to retail , wholesale , factories , households ,other work , import /export……..everything.

Including even farms (livestock , farm produce ,fertilizer )

The older 2007 publication

http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/transport/2007/transport07.pdf

LUAS Dublin tram seems to be the only bright spot recovering past 2007 passenger levels (although it is a much bigger rail network now )

With a 5.1% increase over Y2010 passengers ,now standing at 16.5 million & 12.5 million for the red & green lines.

Whats really a great worry is the decline of Dublin and other areas bus fleets , this after a 20 % ~ drop in countrywide passengers since 2007

In 2007 Dublin bus fleet was 1,145 vehicles

In 2011 Dublin bus fleet was 940 vehicles

In 2007 Cork city bus fleet was 87 vehicles

In 2011 Cork city bus fleet was 78 vehicles.

Mainline domestic (Inter city rail ?) passenger numbers seem to have recovered back to their 2007 levels as they now poach the retired domestic air routes but they face stiff competition from a more liberalized (low wage) inter city Bus service that now uses the almost empty new motorway network.

Y2007 (thousand pas.) :10,537

Y2011 :10,656

However Dublin suburb & DART passenger numbers have collapsed

Y2007 Suburb :13,180

Y2011 :9,911

Dart

Y2007 :20,224

Y2011 : 15,924

However as can be seen across the border these rail declines are almost entirely caused by monetary malice as resource inputs are minimal when trains are full.

(NIR continue to report record passenger numbers)

Air passenger numbers were more or less static over this time although almost all regional airports continue to decline.

Bill,

You usually don’t think much of IMF. What would be your thoughts on this working paper?

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12277.pdf

If your interested I have found a site that has Charts on most of the economic indicators mentioned.

http://www.tradingeconomics.com

Cheers Punchy