Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – October 1, 2011 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

If a nation’s external sector is in balance (and thus making no contribution to real GDP growth) then the private domestic sector will not be able to spend more than it earns (at the current income level) if the government runs a balanced budget.

The answer is True.

This is a question about sectoral balances. Skip the derivation if you are familiar with the framework.

First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses:

(2) Y = C + S + T

where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined).

You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write:

(3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get:

(4) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness.

So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government budget and external:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

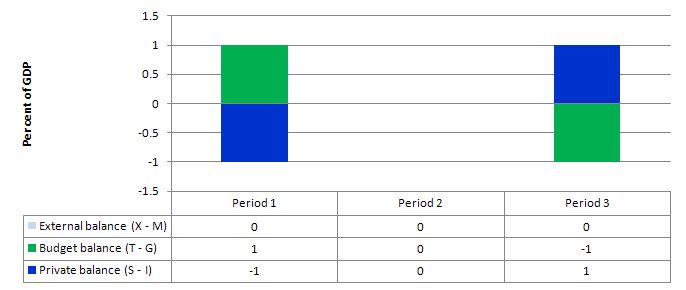

Consider the following graph which shows three situations where the external sector is in balance.

Period 1, the budget is in surplus (T – G = 1) and the private balance is in deficit (S – I = -1). With the external balance equal to 0, the general rule that the government surplus (deficit) equals the non-government deficit (surplus) applies to the government and the private domestic sector.

In Period 3, the budget is in deficit (T – G = -1) and this provides some demand stimulus in the absence of any impact from the external sector, which allows the private domestic sector to save (S – I = 1).

Period 2, is the case in point and the sectoral balances show that if the external sector is in balance and the government is able to achieve a fiscal balance, then the private domestic sector must also be in balance.

The movements in income associated with the spending and revenue patterns will ensure these balances arise. The problem is that if the private domestic sector desires to save overall then this outcome will be unstable and would lead to changes in the other balances as national income changed in response to the decline in private spending.

So under the conditions specified in the question, the private domestic sector cannot save. The government would be undermining any desire to save by not providing the fiscal stimulus necessary to increase national output and income so that private households/firms could save.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

In terms of the initial impact on national income, a tax increase which aims to increase tax revenue at the current level of national income by $x is less damaging than a spending cut of $x?

The answer is True.

The question is only seeking an understanding of the initial drain on the spending stream rather than the fully exhausted multiplied contraction of national income that will result. It is clear that the tax increase increase will have two effects: (a) some initial demand drain; and (b) it reduces the value of the multiplier, other things equal.

We are only interested in the first effect rather than the total effect. But I will give you some insight also into what the two components of the tax result might imply overall when compared to the impact on demand motivated by an decrease in government spending.

To give you a concrete example which will consolidate the understanding of what happens, imagine that the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income is 0.8 and there is only one tax rate set at 0.20. So for every extra dollar that the economy produces the government taxes 20 cents leaving 80 cents in disposable income. In turn, households then consume 0.8 of this 80 cents which means an injection of 64 cents goes into aggregate demand which them multiplies as the initial spending creates income which, in turn, generates more spending and so on.

Government spending cut

A cut in government spending (say of $1000) is what we call an exogenous withdrawal from the aggregate spending stream and this directly reduces aggregate demand by that amount. So it might be the cancellation of a long-standing order for $1000 worth of gadget X. The firm that produces gadget X thus reduces production of the good or service by the fall in orders ($1000) (if they deem the drop in sales to be permanent) and as a result incomes of the productive factors working for and/or used by the firm fall by $1000. So the initial fall in aggregate demand is $1000.

This initial fall in national output and income would then induce a further fall in consumption by 64 cents in the dollar so in Period 2, aggregate demand would decline by $640. Output and income fall further by the same amount to meet this drop in spending. In Period 3, aggregate demand falls by 0.8 x 0.8 x $640 and so on. The induced spending decrease gets smaller and smaller because some of each round of income drop is taxed away, some goes to a decline in imports and some manifests as a decline in saving.

Tax-increase induced contraction

The contraction coming from a tax-cut does not directly impact on the spending stream in the same way as the cut in government spending.

First, imagine the government worked out a tax rise cut that would reduce its initial budget deficit by the same amount as would have been the case if it had cut government spending (so in our example, $1000).

In other words, disposable income at each level of GDP falls initially by $1000. What happens next?

Some of the decline in disposable income manifests as lost saving (20 cents in each dollar that disposable income falls in the example being used). So the lost consumption is equal to the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income times the drop in disposable income (which if the MPC is less than 1 will be lower than the $1000).

In this case the reduction in aggregate demand is $800 rather than $1000 in the case of the cut in government spending.

What happens next depends on the parameters of the macroeconomic system. The multiplied fall in national income may be higher or lower depending on these parameters. But it will never be the case that an initial budget equivalent tax rise will be more damaging to national income than a cut in government spending.

Note in answering this question I am disregarding all the nonsensical notions of Ricardian equivalence that abound among the mainstream doomsayers who have never predicted anything of empirical note! I am also ignoring the empirically-questionable mainstream claims that tax increases erode work incentives which force workers to supply less labour.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

Question 3:

During a recession, a government should use expansionary fiscal policy to restore trend real GDP growth if it wants to reduce unemployment.

The answer is False.

To see why, we might usefully construct a scenario that will explicate the options available to a government:

- Trend real GDP growth rate is 3 per cent annum.

- Labour productivity growth (that is, growth in real output per person employed) is growing at 2 per cent per annum. So as this grows less employment in required per unit of output.

- The labour force is growing by 1.5 per cent per annum. Growth in the labour force adds to the employment that has to be generated for unemployment to stay constant (or fall).

- The average working week is constant in hours. So firms are not making hours adjustments up or down with their existing workforce. Hours adjustments alter the relationship between real GDP growth and persons employed.

We can use this scenario to explore the different outcomes.

The trend rate of real GDP growth doesn’t relate to the labour market in any direct way. The late Arthur Okun is famous (among other things) for estimating the relationship that links the percentage deviation in real GDP growth from potential to the percentage change in the unemployment rate – the so-called Okun’s Law.

The algebra underlying this law can be manipulated to estimate the evolution of the unemployment rate based on real output forecasts.

From Okun, we can relate the major output and labour-force aggregates to form expectations about changes in the aggregate unemployment rate based on output growth rates. A series of accounting identities underpins Okun’s Law and helps us, in part, to understand why unemployment rates have risen.

Take the following output accounting statement:

(1) Y = LP*(1-UR)LH

where Y is real GDP, LP is labour productivity in persons (that is, real output per unit of labour), H is the average number of hours worked per period, UR is the aggregate unemployment rate, and L is the labour-force. So (1-UR) is the employment rate, by definition.

Equation (1) just tells us the obvious – that total output produced in a period is equal to total labour input [(1-UR)LH] times the amount of output each unit of labour input produces (LP).

Using some simple calculus you can convert Equation (1) into an approximate dynamic equation expressing percentage growth rates, which in turn, provides a simple benchmark to estimate, for given labour-force and labour productivity growth rates, the increase in output required to achieve a desired unemployment rate.

Accordingly, with small letters indicating percentage growth rates and assuming that the average number of hours worked per period is more or less constant, we get:

(2) y = lp + (1 – ur) + lf

Re-arranging Equation (2) to express it in a way that allows us to achieve our aim (re-arranging just means taking and adding things to both sides of the equation):

(3) ur = 1 + lp + lf – y

Equation (3) provides the approximate rule of thumb – if the unemployment rate is to remain constant, the rate of real output growth must equal the rate of growth in the labour-force plus the growth rate in labour productivity.

It is an approximate relationship because cyclical movements in labour productivity (changes in hoarding) and the labour-force participation rates can modify the relationships in the short-run. But it provides reasonable estimates of what happens when real output changes.

The sum of labour force and productivity growth rates is referred to as the required real GDP growth rate – required to keep the unemployment rate constant.

Remember that labour productivity growth (real GDP per person employed) reduces the need for labour for a given real GDP growth rate while labour force growth adds workers that have to be accommodated for by the real GDP growth (for a given productivity growth rate).

So in the example, the required real GDP growth rate is 3.5 per cent per annum and if policy only aspires to keep real GDP growth at its trend growth rate of 3 per cent annum, then the output gap that emerges is 0.5 per cent per annum.

The unemployment rate will rise by this much (give or take) and reflects the fact that real output growth is not strong enough to both absorb the new entrants into the labour market and offset the employment losses arising from labour productivity growth.

So the appropriate fiscal strategy does not relate to “trend output” but to the required real GDP growth rate given labour force and productivity growth. The two growth rates might be consistent but then they need not be. That lack of concordance makes the proposition false.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 4:

In many nations, private households are increasing their saving ratios (from disposable income) and firms are declining to invest. To avoid employment losses, these developments signal the need for expanding public deficits.

The answer is False.

The answer also relates to the sectoral balances framework outlined in detail above. When the private domestic sector decides to lift its saving ratio, we normally think of this in terms of households reducing consumption spending. However, it could also be evidenced by a drop in investment spending (building productive capacity).

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms layoff workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession. Interestingly, the attempts by households overall to increase their saving ratio may be thwarted because income losses cause loss of saving in aggregate – the is the Paradox of Thrift. While one household can easily increase its saving ratio through discipline, if all households try to do that then they will fail. This is an important statement about why macroeconomics is a separate field of study.

Typically, the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur – in the form of an expanding public deficit. The budget position of the government would be heading towards, into or into a larger deficit depending on the starting position as a result of the automatic stabilisers anyway.

So an intuitive reasoning suggests that a demand gap opens and the only way to stop the economy from contracting with employment losses if it the government fills the spending gap by expanding net spending (its deficit).

However, this would ignore the movements in the third sector – there is also an external sector. It is possible that at the same time that the households are reducing their consumption as an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public budget balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving ratio if net exports were strong enough.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Saturday Quiz – May 22, 2010 – answers and discussion

Premium Question 5:

If the external sector is accumulating financial claims on the local economy and the GDP growth rate is lower than the real interest rate, then the private domestic sector and the government sector can run surpluses without damaging employment growth.

The answer is False.

When the external sector is accumulating financial claims on the local economy it must mean the current account is in deficit – so the external balance is in deficit. Under these conditions it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the national accounting rules and income adjustments will always ensure that is the case.

The relationship between the rate of GDP growth and the real interest rate doesn’t alter this result and was included as superflous information to test the clarity of your understanding.

To understand this we need to begin with the national accounts which underpin the basic income-expenditure model that is at the heart of introductory macroeconomics. See the answer to Question 1 for the background conceptual development.

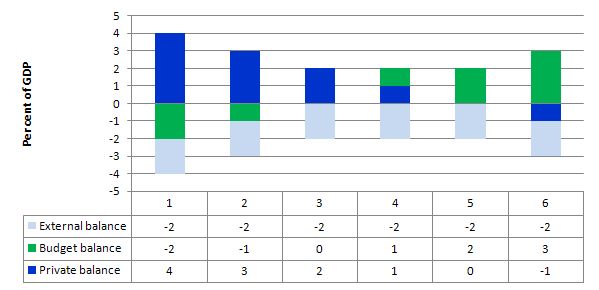

Consider the following graph and associated table of data which shows six states. All states have a constant external deficit equal to 2 per cent of GDP (light-blue columns).

State 1 show a government running a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP (green columns). As a consequence, the private domestic balance is in deficit of 4 per cent of GDP (royal-blue columns). This cannot be a sustainable growth strategy because eventually the private sector will collapse under the weight of its indebtedness and start to save. At that point the fiscal drag from the budget surpluses will reinforce the spending decline and the economy would go into recession.

State 2 shows that when the budget surplus moderates to 1 per cent of GDP the private domestic deficit is reduced.

State 3 is a budget balance and then the private domestic deficit is exactly equal to the external deficit. So the private sector spending more than they earn exactly funds the desire of the external sector to accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue in this country.

States 4 to 6 shows what happens when the budget goes into deficit – the private domestic sector (given the external deficit) can then start reducing its deficit and by State 5 it is in balance. Then by State 6 the private domestic sector is able to net save overall (that is, spend less than its income).

Note also that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances). This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts.

Most countries currently run external deficits. The crisis was marked by households reducing consumption spending growth to try to manage their debt exposure and private investment retreating. The consequence was a major spending gap which pushed budgets into deficits via the automatic stabilisers.

The only way to get income growth going in this context and to allow the private sector surpluses to build was to increase the deficits beyond the impact of the automatic stabilisers. The reality is that this policy change hasn’t delivered large enough budget deficits (even with external deficits narrowing). The result has been large negative income adjustments which brought the sectoral balances into equality at significantly lower levels of economic activity.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Thanks Bill,

I really like your ‘trick questions’ as they force me to use my brain. In that sense they are not ‘trick questions’ at all – their purpose is more important than that.

Re question 1.

In another post, I think you said something along the lines of “Because the Howard govt ran a surplus for so long, the non-govt sector could only spend by going into debt.”. If this and your answer to 1 are right, does this mean that the private sector borrowing in that period was all ultimately funded by overseas?

Michael,

“If this and your answer to 1 are right, does this mean that the private sector borrowing in that period was all ultimately funded by overseas?”

My answer would be no, because the question specifically states that the externals balance is zero (in balance).

Oh yes, I know the question says “external balance is zero”. That’s the point: in the real world, we know the Howard govt was running surpluses. And yet, if I remember the claim right, there was lots of spending in the private sector too. So, perhaps the excess money was coming into Australia from overseas. Alternatively, perhaps the consumers were running up huge debts to financial institutions (the net position of the whole private sector could be in deficit, but internally, there clearly might be surpluses internally).

To add to which, I’m a bit confused by the fact that external trade has an impact. If trade is in AUD, then presumably one can treat the whole world as the private sector, but I guess trade is in an external currency (USD). If so, does the government feel compelled to print AUD to honour USD conversion requests? Otherwise I’m confused: the standard accounting principle seems to suggest that there are two possible sources of money for the private sector: govt money creation (running a net deficit), and trade. But where do the units of currency come from for trade?

Or maybe: trade doesn’t create new units of currency; it just repatriates AUD that are held elsewhere. Then, if terms of trade are in Australia’s favour, the local private sector can run a surplus. (Presumably the AUD goes up in value wrt other currencies at the same time because the govt’s surplus ensures there are fewer of them about.) Which returns me to my original question: were the Howard govt and the Australian private sector both able to run surpluses wrt each other because of AUD being sucked in from overseas?

If Tom Hickey reads this, would you be willing to post this at R. Wray’s blog? For some reason, it won’t accept my comments (not sure why but would like to find out).

“Getting caught up.

“I owe taxes to the government and these are measured in so many Dollars. It is my debt and the government’s asset and we can record it on electronic balance sheets.”

I believe an economy can function with no private debt and no gov’t debt. I don’t see what taxes have to do with debt. I think you need some different/new terms. It seems to me taxes would be more like some type of liability.

“Now, I could borrow a cup of sugar from you and write “IOU a cup of sugar”.”

And, “Now clearly I am not done. I’ve got a house and a car (and maybe some sugar in the kitchen cabinet). Assume I’ve got some debt against them, as I took out a loan (issued my own IOU to the bank or auto finance company, etc).”

I’m thinking the sugar and home/auto example have some differences that to me are important.

“When I go to tally up all of my wealth I will include all the Dollar IOUs I hold against banks, the government, other financial institutions, friends and family and so on. That is my gross financial wealth. (It could include even some of those “real cup of sugar IOUs” if there is a reasonable expectation that I could collect Dollars from those owing me sugar.) Against that I count up all of my own IOUs-to banks, government, family and friends.”

Down further in the post you talk about demand deposits and loans. IMO, it would much easier for someone to follow if you used currency and demand deposits (the medium of exchange) and loans/bonds.

“You can go through an infinite number of scenarios and you will see that it all goes back to a loan. Think about it this way: all bank deposits came from bank keystrokes created when banks accepted IOUs of borrowers. So all purchases with demand deposits have a loan somewhere in the background. The demand deposit is a bank IOU, created when the bank accepted an IOU.”

***First and the way the system is set up now, I believe that also applies to the gov’t. If so, does that mean that all NEW medium of exchange has to be the demand deposits created from a loan/bond whether it is private debt or gov’t debt?

*** If that is also true, that is very, very important!!! I believe that is where the problem in the economy is along with a few assumptions about the economy that don’t have to be true.

“The exception is the government. If I sell the gold to the government, it credits my demand deposit and credits the bank’s reserves. A gold purchase by government is exactly the same as a Social Security payment, except that the government now has to go to all the bother of locking up the gold and keeping the bandits away so that the gold does not get freed and put to superior use as dental crowns in mouths. (That makes a heckuva lot of sense, doesn’t it. We need to start a campaign: free the gold!)”

It seems to me if the central bank is targeting a non-zero overnight rate, then the central bank reserves will be most likely removed with taxes and/or selling a gov’t bond (see the two *** above)

“What I am getting at is that the private sector does not need to “go into debt” to get “money” so long as the government supplies it.”

What I am getting at is that it does not have to be the gov’t that supplies it. Why isn’t this possible?

savings of the rich plus savings of the lower and middle class = the balanced budget(s) of the various level(s) of gov’t plus the dissaving of the currency printing entity with currency and no bond/loan attached

That seems to me to give the best chances of productivity gains and other things being distributed evenly between the major economic entities and evenly in time.

Oops, forgot the link:

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/2011/09/real-vs-financial-accounting-responses.html

Michael Norrish said: “Otherwise I’m confused: the standard accounting principle seems to suggest that there are two possible sources of money for the private sector: govt money creation (running a net deficit), and trade. But where do the units of currency come from for trade?”

Very good question. Let’s replace money (too many definitions) and units of currency with medium of exchange. IMO, domestically, and the way the system is set up now, it is demand deposits from private debt and/or gov’t debt. IMO, it is the same way for the foreign sector (demand deposits from private debt and gov’t debt in the foreign currency). There is how too much debt comes about (whether private or gov’t). IMO, it is the demand deposits from debt that is the stock that flows around the “budgets” of the major economic entities.

Michael Norrish, it seems to me non-gov’t sector savings = gov’t deficit is not specific enough.

It seems to me this is a better way to handle questions that are like Q1 and Q4:

current account deficit = gov’t deficit plus private sector deficit

IMO, the best way is:

current account deficit = gov’t deficit plus currency printing entity deficit plus private sector deficit (deaggregated, or broken down, properly)

Bill,

As far as Question 1 and Question 5 are concerned, I consider Question 1 as False and Question 5 as True due to the following logic:

If the government sector runs a balanced budget, the domestic private sector could still spend more than it earns, thus not hindering growth, by expanding credit (leverage/going into debt). While this is not a sustainable strategy, it can last for some years before the economy becomes Ponzi and the “sudden” deleverage creates a spending gap (recession). So, there is still a possibility for a balanced budget (or even surplus) not undermining growth (as you ask in Question 5) and the private sector’s ability to spend more than it earns (as you ask in Question 1), if the private sector increases its debt (leverage).

@ Fed Up

I sent it but it hasn’t shown up yet. Maybe in moderation?

I’m not sure I understand your explanation of question #1. During the late 1990’s the government ran surpluses at the same time the private sector spent massively in a credit boom, i.e. it effectively created its own money as none was forthcoming from the government sector. It appears to me that the private sector will find a way to do what it wants regardless of government action, and with disastrous results.

I probably should have specified the American government ran surpluses. Sometimes I forget this is an Australian blog.

I’m with ‘MMT in Greece’ on this.

In question one the private sector — whether business or household or both — can go into debt to expand GDP. In doing so they might even inflate asset bubbles — a housing bubble for example. None of this is good policy, but it does seem to work.

Maybe I’m missing something here, but question two seems to be dependent upon what is constituted by ‘government spending’. In your example — i.e. of a direct order for a commodity — it is indeed less damaging as it is directly removed from the economy. However, if we consider a case in which the $1000 in spending is taken out of a fireman or a policeman’s wages, the effects should be the same as the tax increase (assuming, of course, that the fireman and the policeman are the one’s being taxed).

In short, it needs to be specified what the government spending is going toward in order to answer the question. (If you think about it a bit more you also have to specify the tax increase, as if it’s a tax on, say, inheritance it may have even less effect than in your example).

Dear MMT in Greece (at 2011/10/02 at 19:27)

Question 1:

It isn’t as simple as you think. The situation outlined in the question is for a given (static) level of GDP. If the private sector tried to do what you say then the Budget would not remain in balance nor would the external sector remain in balance because income changes would render the necessary adjustments. But if the external sector and the budget sector was in balance, then the private domestic sector has to be in balance as the level of GDP so determined.

Question 5:

Same goes here.

The sectoral balances have to hold – there is no question of that – it is not a matter of opinion. What you have to then appreciate is that driving the show are income changes – each of the three balances is sensitive to GDP changes and it is the latter that ensures the balances ultimately adjust to the accounting rules. The interest is in how those adjustments work rather than the final result which is an accounting dictate.

best wishes

bill

Dear Philip Pilkington (at 2011/10/03 at 7:55)

The question is not dependent on nuances concerning government spending. The definition of government spending is standard in the National Income and Production Accounts terminology.

The point is that G impacts directly on National Income whereas T impacts on Personal Disposable Income. That is a big difference and is what the question was exploring.

best wishes

bill

ps I hope you are now not in agreement with MMT in Greece – see my response in that regard.

Dear Ben Wolf (at 2011/10/03 at 7:21)

While the private sector can “do what it wants” (to some degree) – what it does impacts on national income changes which then impact on the other two sectoral balances. There can be no dispute that the sectoral balances have to add to zero (as an accounting matter) and it is GDP changes that drive that once the behaviour in one or more of the sectors change.

best wishes

bill

ps that is independent of whether we are talking about Australian National Accounts or US National Accounts or Wherever National Accounts.

Sectoral balances 101 question:

Since all spending is also someone’s income, isn’t it impossible for the private domestic sector to spend more than it earns, regardless of how much it borrows, unless the recipient of the spending enabled by the borrowing is in either the public or external sector?

Dissaving of the borrowing entity is matched by the saving of the recipient of the spending, isn’t it? Unless the two entities lie within different sectors, the intrasectoral sum of expenditure minus earnings is zero. Am I stating the obvious, or just being boneheaded? It’s not the borrowing per se that enables a sector to go into a negative balance, all that matters is where the borrowed money is spent. Or so it seems to me.

I’m a bit confused here. Okay, let’s ignore the external sector — just pretend it doesn’t exist.

Private sector spends more than it earns by taking on debt. This is new money created by the banking system (loans create deposits). The government balances it’s budget by taxing the same amount as it’s spending (some of this tax is on the newly created private sector money). So, the government budget is balanced, GDP is at whatever level it is at and the private sector is spending more than it is earning.

What’s the problem here?

I checked out the NIPA and they seem to classify ‘government consumption expenditures’ and ‘gross investment’ together as a single entity under ‘government spending’:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Income_and_Product_Accounts#Table_2:_Production_sources_of_gross_domestic_GDP

As I said in my original comment, if the government spending is taken out at the ‘gross investment’ level (i.e. is taken out of investment in policemens’ wages) the effects will impact Personal Disposable Income directly.

Dear Philip Pilkington (at 2011/10/03 at 20:30)

Where is the private spending going? Who is receiving that income? Spending = Income. So if there is a closed economy (your example) and the G = T, then S has to equal I.

Sorry.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

You’re right of course. I wasn’t aggregating the private sector. That was silly.

Still, my NIPA criticism might hold water… maybe not though…

So your point is that while the private sector can “run wild” for a time, in the long run the books have to balance out. That makes more sense to me, thanks for the response.

Tom Hickey, thanks. I’ll check on it.

Tom Hickey, it’s not there. I tried posting again. It still won’t work. Not sure what is wrong. Thanks!