I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Reality check for the austerians

Individuals often carry history on their shoulders by virtue of the positions they hold and the actions they take. When these individuals hold views about the economy that are not remotely in accord with the way the system operates yet can influence economic policy by disregarding evidence then things become problematic. It is no surprise that my principle concern when it comes to economics is how we can keep unemployment and underemployment low. That was the reason I became an economist in the late 1970s, when unemployment sky-rocketed in Australia and has been relatively high ever since. So when I read commentary which I know would worsen unemployment (levels or duration) if the opinion was influential I feel the need to contest it. That has been my motivation in economics all my career. A daily contest given that the mainstream of my profession is biased to keeping unemployment and underemployment higher than it otherwise has to be. Today I present a simple reality check for the austerians.

When I read that in February of this year, the Republican extremist Ron Paul chaired his first meeting of the House Monetary Policy Subcommittee because the Republican won the mid-term US elections, I became anxious. Ron Paul is clearly dedicated to reducing unemployment so in that sense he cares about the same things as I do.

He also believes that economic policy is deliberately keeping unemployment high – see this Interview which was conducted just before he chaired his first Monetary Policy Subcommittee meeting in February. I agree with the general proposition – economic policy is making unemployment worse – but not in the way Ron Paul thinks.

But reading the transcript of that interview further you realise that his Austrian-school views on monetary policy leads him to predict Armageddon as a result of his interpretation of the recent conduct of the US Federal Reserve (quantitative easing) and the US Treasury (budget deficits and debt). My reading of his views lead me to conclude that his appointment to that role can only end up creating negative outcomes for the unemployed.

His views (Austrian extremist) and those of the mainstream of my profession share common ground which is now the base upon which macroeconomic policy is being made. The common ground is:

- Persistent budget deficits will stifle growth because they push interest rates up and crowd out private enterprise.

- Persistent budget deficits and quantitative easing will lead to inflation with a risk of hyperinflation.

- Persistent budget deficits ultimately lead to government insolvency where debt holders are left stranded.

They also raise issues of inefficient use of resources when deployed by the government and loss of incentive to private enterprise through taxes etc. which I will leave alone today.

As background for today’s blog you might like to read – Budget deficit basics and the suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

Paul’s elevation to influence was the subject of a recent eulogy by well-known Austrian-school commentator and author Tom Mullen who had the audacity to claim that – Austrian Economics Is Scientific (Keynesianism Is Not) – in an article he wrote in February 2011.

I was reminded of this when I read French financial commentator Erwan Mahé’s May 2011 Newsletter (entitled Thaler’s Corner) which I received by E-mail today. The title of his May offering is The huge and highly dangerous Austrian School experiment!.

Mahé correctly indicates that governments everywhere have fallen prey to the fears about public debt and deficits that are being whipped up by conservatives who demonstrate little understanding of how poorly the empirical world maps into their theories – hence his conclusion that it is a “huge and highly dangerous … experiment”.

He cites the rising influence of the Tea Party in the US (“fuelling popular hysteria about unsustainably high government deficits”); the harsh fiscal contraction in the UK which have turned a growing economy back into a near-recessed, going backwards economy; the anti-growth German fiscal rules that have now been embedded in their Constitution and which the French government is now under pressure to replicate; “The slew of austerity plans in eurozone peripheral nations, which will guarantee that they remain in a deep recession characterised by persistently high unemployment for a long time to come”; the refusal of the Bank of Japan to use its capacity to finance the reconstruction while the Japanese government is seeking to raise taxes despite the nation being locked into a recessed/deflationary cycle for the last two decades.

It is a very insightful article and touches on many of the main themes of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) which I traverse regularly in this blog.

So I thought today I would consider some of these themes in brief with some empirical evidence to help. Why empirical evidence? Answer: Apparently, Tom Mullen (and Ron Paul) think we need it to decide which views are to be considered worthy of the eye of policy makers.

Mullen wrote:

Anyone who has taken a basic chemistry class in high school remembers how you prove or disprove a theory. You conduct experiments to determine whether the predictions that your theory makes are correct. For example, your theory might predict that mixing two colorless chemicals in a test tube will result in the mixture turning blue. To prove it, you must not only conduct the experiment once, but over and over again, yielding the same result. If your test tube turns blue under the same conditions every time, you have proven your theory. If not, your theory is considered invalid and a new one must be formulated …

Imagine that you are back in your high school chemistry class lab, conducting experiments. In the row behind you, an Austrian economist is testing his theory. The test tube turns blue one time after another, just as he predicted it would. In the row ahead, a Keynesian economist is testing his theory. His test tube turns a different color every time and then finally explodes, lighting his beard on fire. Which one would you deem the better scientist? Which one would you bet your life savings upon in the next experiment? If you wish to take the scientific approach, listen to the Austrians.

In between the two pieces quoted is a rail against “Keynesians” – like “Austrian economists like F.A. Hayek predicted the Great Depression when the Keynesians said that the economy was fine”. As an historical note, there were no Keynesians at the onset of the Great Depression. This historical reinvention by Mullen permeates his whole article and his book – A Return to Common Sense: Reawakening Liberty in the Inhabitants of America.

Let’s also ignore the fact that in sophistical research centres, social science is not conducted at all remotely like a chemist would explore a “controlled” experiment. Social science has no control and we don’t test theories in any crude Popperian manner. That doesn’t mean we do not seek to develop theories that a tentatively adequate representations of the reality we are interested in.

Yes, I know all reality is relative but we will stay modernist here for today.

A tentatively adequate representations is conditioned on the data and if we find the data doesn’t accord with what we might have “predicted” then we have to reconsider our representations. But we are not testing truth. We cannot do that because we wouldn’t know what the truth was if we found it. It is better to consider all our representations, models, conjectures etc as being false but better or worse in terms of capturing the patterns around us.

So if we use long historical data sets and consistently observe one set of relationships then we might be comfortable with theoretical positions that are based on that set of relationships. If we fail to observe (ever) a relationship then any body of theory that predicts that relationship is not likely to be helpful.

What about the claim that the rise in public debt in the UK or the US or Japan is going to end up in the insolvency of their respective national governments?

Remember that in the mid-1990s conservative economists (including Austrian-schoolers) were predicting this about Japan. Sixteen years later no default, no insolvency, no loss of private debt market access.

When have the governments of the UK, the US, or Japan defaulted because they have run out of money? Answer: never. Reasonable conclusion based on the body of evidence: there is no default risk for sovereign nations that issue their own currency and do not borrow in foreign currencies.

So proposition number one that dominates the “debt is bad” lobby has no empirical backing and should be disregarded.

What about the hyperinflation argument? Which one do you want to read about first, the deficit or the monetary base relationship with inflation?

The Austrians, in particular, as continually warning that the monetary base expansion in the US will cause hyperinflation. They consider the quantitative easing which has seen the balance sheets of the central banks in Britain, the US and Japan (among others) expand significantly in recent years to be the source of an impending disaster.

As Mahe points out these central bank measures are just an:

“asset swap” in investors’ balance sheets between bonds and cash, which end up in the Fed in the form of surplus reserves. In any case, these reserves are useless for commercial banks and do not create more lending (“loans create deposits”!). For that to occur, there needs to be “real credit demand”, which meet the credit requirements stiffened considerably since 2007.

Austerity programs by national governments, which will surely worsen the already excessive unemployment, have no authority. They have convinced us that that quantitative easing in some way puts more spending power into the hands of consumers and thus fuels inflation. An asset swap among savers is not inflationary.

Please read my blog – Quantitative easing 101 – for more discussion on this point.

As Mahé points out if the central bank started meeting the Treasury deficit by “real money creation” – which should be taken to mean the central bank crediting private bank accounts on behalf of the Treasury – then that could be inflationary:

… to the extent that the other inflation factors are present (absence of output gap, inflation expectations, etc.).

Any spending private or public will be inflationary if the other factors are present. It is spending that carries an inflation risk not the monetary operations that may be associated with it.

The data used here comes from the official sources. I realise some of the extreme Austrian-schoolers go into denial when it comes to data and claim that there is a conspiracy by the governments around the world to produce spurious data to cover their tracks. At that level of irrationality I give up.

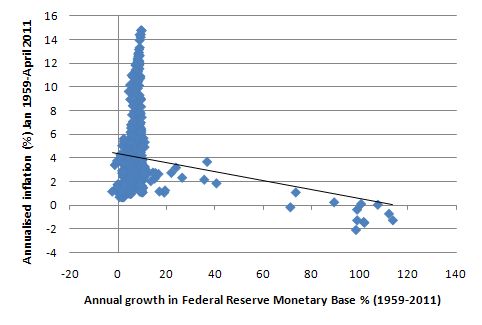

The first graph shows the relationship between the monetary base and inflation using quarterly seasonally-adjusted data from January 1959 to April 2011. The monetary data is from the US Federal Reserve – Table 1: Aggregate Reserves of Depository Institutions and the Consumer Price Index data is from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The black line is a simple linear regression. If anything the relationship is negative – when the base expands, annual inflation falls although I wouldn’t want to hang anything on a simple linear regression. I could draw the same graph using lags and leads of the variables (to take into account the argument that the inflation pressure builds up over time) with the same result.

The reasonable conclusion based on the body of evidence is that there is no systematic relationship between the monetary base and the annual inflation rate in the US. I could also draw all the graphs I present here for other advanced nations with similar outcome.

So for mainstream economists and Austrians who are locked in to the Quantity Theory of Money and the money multiplier there is no evidence to support these theoretical “beliefs”. They are artifacts of religious doctrine only.

Please read my blog – Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

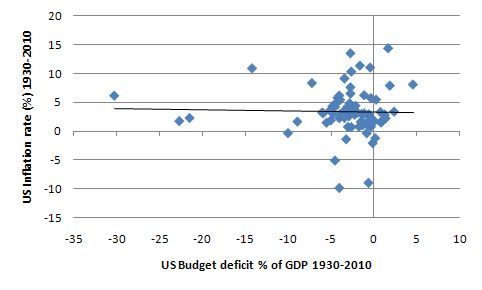

The next graph considers the relationship between the budget deficit (as a per cent of GDP) and the annual inflation rate in the US from 1931 to 2010. The annual CPI data comes from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (it is their annual series equivalent of the quarterly data used in the previous graph) and the The US Office of Management and Budget provide historical budget data back to 1930.

The black line is a simple regression although I don’t wish to push the authority of that regression. It is just an indicator that has to be considered.

Again, I could lag the data to the same effect. I would get the same result for other advanced nations.

I will come back to an important point about why the graphs look like this later.

What about the relationship between budget deficits and interest rates?

It is clear that at any point in time, there are finite real resources available for production. New resources can be discovered, produced and the old stock spread better via education and productivity growth. The aim of production is to use these real resources to produce goods and services that people want either via private or public provision.

So by definition any sectoral claim (via spending) on the real resources reduces the availability for other users. There is always an opportunity cost involved in real terms when one component of spending increases relative to another.

However, the notion of opportunity cost relies on the assumption that all available resources are fully utilised.

Unless you subscribe to the extreme end of mainstream economics which espouses concepts such as 100 per cent crowding out via financial markets and/or Ricardian equivalence consumption effects, you will conclude that rising net public spending as percentage of GDP will add to aggregate demand and as long as the economy can produce more real goods and services in response, this increase in public demand will be met with increased public access to real goods and services.

If the economy is already at full capacity, then a rising public share of GDP must squeeze real usage by the non-government sector which might also drive inflation as the economy tries to siphon of the incompatible nominal demands on final real output.

However, the argument against budget deficits is about their alleged impact on interest rates and the concept of financial crowding out which is a centrepiece of mainstream macroeconomics textbooks. This concept has nothing to do with “real crowding out” of the type noted above.

The financial crowding out assertion is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention. At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking.

The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

At the heart of this erroneous hypothesis is a flawed viewed of financial markets. The so-called loanable funds market is constructed by the mainstream economists as serving to mediate saving and investment via interest rate variations.

This is pre-Keynesian thinking and was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving. So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

So saving (supply of funds) is conceived of as a positive function of the real interest rate because rising rates increase the opportunity cost of current consumption and thus encourage saving. Investment (demand for funds) declines with the interest rate because the costs of funds to invest in (houses, factories, equipment etc) rises.

Changes in the interest rate thus create continuous equilibrium such that aggregate demand always equals aggregate supply and the composition of final demand (between consumption and investment) changes as interest rates adjust.

According to this theory, if there is a rising budget deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending.

So allegedly, when the government borrows to “finance” its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment.

The mainstream economists conceive of this as the government reducing national saving (by running a budget deficit) and pushing up interest rates which damage private investment.

Please read the trilogy of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more detailed explanation.

The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash! It is true that the private sector might wish to spread these financial assets across different portfolios. But then the implication is that the private spending component of total demand will rise and there will be a reduced need for net public spending.

Further, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. But government spending by stimulating income also stimulates saving.

Additionally, credit-worthy private borrowers can usually access credit from the banking system. Banks lend independent of their reserve position so government debt issuance does not impede this liquidity creation.

Mahé also thinks the crowding out idea is “stupid” because:

… a hike in a country’s budget deficit automatically creates wealth of private-sector economic agents!

Budget deficits do this in two main ways: (a) they push up private savings; and (b) they push up corporate profits.

First, when the government net spends it increases demand and national income. Private saving is a function of income growth. This saving is held as deposits in the banking system or is invested in financial assets such as government bonds. As above – it is a wash with respect to government borrowing its own spending back.

If the saving sits in the banking system as excess reserves then there is downward pressure on interest rates. I explain that in the deficit trilogy – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

Second, Mahé also invokes the Kaleckian profits equation that shows that after-tax corporate profits) are equal to private capitalist consumption, investment, budget deficits, trade surpluses less employee savings.

I explain how this works in this blog – Why budget deficits drive private profit.

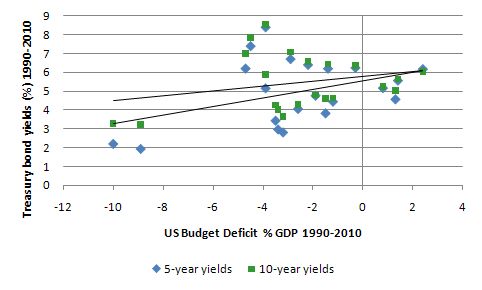

But what about the relationship between interest rates and budget deficits? We can consider the treasury yields and the corporate bond rates.

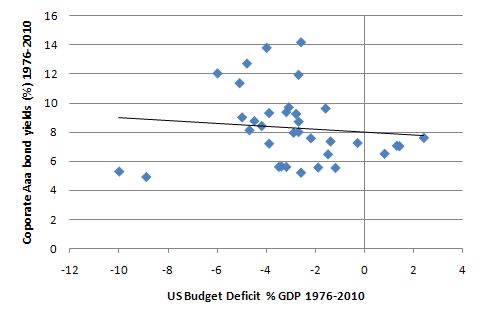

The US Treasury provide Daily Treasury Yield Curve Rates back to 1990. The US Federal Reserve also provides historical data – Selected Interest Rates (Daily) – H.15 – which has Corporate Bond Rates for AAA- and BBB-rated debt back to 1976.

The deficit data is from the OMB as before.

First, the following graph shows the relationship between the US budget deficit and 5-year and 10-year Treasury bond yields from 1990 to 2010. The black lines are the respective simple linear regression relationships.

The reasonable conclusion based on the body of evidence is that there is no systematic relationship between the US federal deficit and the long-term bond yields in the US. I could also draw all the graphs I present here for other advanced nations with similar outcome.

What about the corporate bond rate? The following graph shows there is no relationship between the two either.

Conclusion

Clearly, simple graphical eyeballing is not conclusive proof of anything. But after a relatively long career of examining data one gets a good feel for relationships between economic variables.

My experience tells me that if a simple graph doesn’t support a relationship more sophisticated econometric analysis will not help much. The latter provides more precision and has sampling properties that might console a researcher but if a simple chart cannot find anything then further modelling is unlikely to be worth pursuing.

The first thing I do when I examine data (prior to econometric analysis) is to plot the series involved.

But when considering the economics of these relationships you have to understand the context. Budget deficits are endogenous balances – that is, largely beyond the control of governments and hence driven by private spending and saving decisions. The stronger the private spending, the lower will be the budget deficit (typically).

So when budget deficits rise significantly – as they have in recent years – we know that this is because private spending is so weak and output growth is contracting or weak.

Central banks tend to react to these circumstances by cutting interest rates and any demand pressure on inflation subsides (or causes deflation). Private borrowing falls despite the reduced interest rates because there is not enough aggregate demand (spending) to justify investment by firms or longer-term commitments to debt by households.

These cyclical swings drive the relationships that we observe in the graphs I have presented. It is no surprise that budget deficits are associated with lower inflation, lower interest rates and lower investment. The causality is through the income-generating system. All these economic indicators are sensitive to the business cycle.

The problem with the mainstream body of thought is that they largely deny these linkages and so miss the reality.

The other problem is that policy makers listen to their twisted versions of the way the system works. Just a few charts would show the governments why they should disregard the mainstream of my profession.

Digression: Oh Dear

Private lives are just that.

But I thought this little headline on the ABC News site this morning was an overstatement:

I suppose operational might include imposing harsh pro-cyclical policy regimes onto nations that need growth more than anything.

In the IMF press release we read that:

… The IMF remains fully functioning and operational.

Clearly functioning doesn’t necessarily mean functional.

I was also amused with the UK Guardian’s assessment – that the champagne socialist had “moved the fund in a more progressive direction”. I suppose when you start out as extremists and move to a little right of Genghis Khan that is progression.

That is enough for today!]]>

I’ve just heard what the defence is going to be.

Although It’s a thin line between between being rescued and being assaulted, this was in fact an act of altruism by the great man.

This is a relatively simplistic analysis, especially when trying to use international comparisons. In Japan, for instance, their government has funded itself using domestic savings which are artificially high due to the persistent trade surpluses. They have not had to meet their borrowing requirements externally which would have pushed up interest rates. Interestingly, a similar phenomenon happened during the Dutch-Spanish wars when the Dutch funded their independence via domestic savers from the merchant class and interest rates actually fell. Domestic savings being recycled into government coffers is an argument that has been used to explain why western governments did not default on their bonds post-WW2.

The UK is in a completely different position than either Japan, US or Europe. It has a very high budget deficit when compared to their peers but are reliant on international lenders. When you are reliant on this inward investment, you become reliant on a number of factors outside of your control. Regardless of whether austerity would be imposed or not, the international uncertainty would still have damaged UK growth prospects but the austerity package means that bond traders/lenders are no longer questioning whether the Government will ever repay their debts. Therefore, the net impact is that the UK is perceived as being safer than other investment locations.

The market, the lenders, have spoken and are concerned about future inflation. If you decide to break-down the issuance of bonds, particularly in the UK, the number of inflation-linked bonds has dramatically increased. Many people are concerned that governments will try to inflate their way out of trouble. Therefore, lenders are using inflation-linked bonds to protect their investment but it leads to an inability to inflate their troubles away.

I can go on in this vein for a while. Suffice to say, I will end with this note. PIMCO, the world’s largest bond fund manager, estimates that 70% of the demand for US Treasuries is due to the US Federal Reserve. Hence the low interest rates (and the consequent impact on crowding out in other tradeable asset classes). PIMCO has decided to shift their investments away from US Treasuries into other securities with a safer fiscal and monetary policies. These guys analyse countries for a living. If they are wrong then they get fired, if you are wrong you keep your job. Who should I believe?

There is a very good demolition of the assumption underlying the classical Quantity Theory assumptions at Forbes:

http://blogs.forbes.com/johntharvey/2011/05/14/money-growth-does-not-cause-inflation/

http://gregmankiw.blogspot.com/2011/05/evaluating-arra.html

comments?

” In Japan, for instance, their government has funded itself using domestic savings which are artificially high due to the persistent trade surpluses.”

You have the causality the wrong way around. The government deficit has funded the domestic savings in bonds which is domestic because the country runs a trade surplus. In those countries with a trade deficit the savings appear to be foreign derived simply because of the arithmetic.

“They have not had to meet their borrowing requirements externally which would have pushed up interest rates.”

Who else issues Yen? Where did the Yen come from in the first place? The money has to have come from the central bank first, otherwise you can’t “borrow” it.

Why is the government borrowing from third parties when it owns an entire bank? Why not just get an interest free ‘loan’ from them?

That is why classical economics fails. It just doesn’t stack up in the logic department.

Sean

The UK is different to Eurupe as the UK is the issuer of its currency, and therefore, do not have to fund anything. Therefore, if “international lenders” do not want the bonds, then they can stop issuing the boinds. If they have to issue the bonds because of the law, then the Bank of England can purchase bonds the secondary market, and provide demand for the bonds. Japan, and the US are exactly the same. Euro dollar using countries are just that, Euro using countries, and must fund their debt via taxes and bond issues. If international lenders do not want euro dollar government bonds then the relevant country needs to go cap in hand to the ECB and ask them to bend the rules and provide them with Euros.

Neal

Sean

Just because PIMCO gets fired if they get it wrong doesn’t mean that they are right. Also, it means that you need to look for motive behind their comments. They might be talking down Treasuries to pick them up on the cheap when everyone else sells them, and the talk them back up later and pick up a tidy profit, and therefore, commissions to themselves.

And who says that they would get fired if they screw up? They might just be bailed out by the Fed Reserve and/ US Treasury if the last 3 years are any guide.

Neal

I am afraid Neil that your comments regarding Japanese savings and Yen issuance are a little hard to follow. Are you saying that the deficit is being recycled into excess savings? That would be partly true but is not the root cause for the high savings rates amongst individuals and companies. The trade surpluses which are sitting as excess cash on the balance sheets of companies (incl. pension funds and banks) are recycled into Government debt because it is considered risk-free. However, as the population ages, savings are liquidated for people to spend. This makes it harder for the Japanese Government is issue bonds to their domestic populace via the banks, forcing them to borrow from the outside. At this moment, it is 95% domestic issuance vs. 5% foreign although it is bound to change.

Your Yen commentary is equally bizarre. I am talking about the supply-demand characteristics in the bond market. If you have to go to an outside source of financing, then they would not be attracted to 0.5% interest rates forever. If you are tying to make a case for the “printing press” to be turned on (as opposed to overseas borrowing because of the conditions) then I am sure people would have both moral, ethical and economic concerns about this.

I try not to go down the road of theoretical economics but rather see what happens in practice and what the markets are prepared to tolerate.

Neil B,

Going into the secondary market because lenders believe you are a high credit risk is a spurious way of running your country. It keeps interest rates artificially low but refuses to fix the underlying problems in an economy. Indeed, it is the easy way out rather than showing any spending discipline and assumes that you (the issuing government) is right and the lenders are wrong. Also, you should ask what happens when the government actively intervenes in an economy to keep rates low – where do international fund managers put their money? Either they find higher risk activities (which have a higher risk of blowing up) or they move their funds overseas. Suddenly a policy decision to keep rates low has consequent investment impacts in the private sector. You need to think about the reprocussions from your decisions.

The comment about PIMCO is right – what are their motives? In short, it is to make money. However, keeping ones job is an important consideration too. these guys have “skin in the game” whereas academics have the joy of failure without the side effect of creative destruction. In any case, if people dump Treasuries then the price is driven lower so buying if people are dumping them will result in a capital loss and will require the Fed to become, yet again, the largest buyer in order to drive yields down.

What does it tell you when a country is viewed so poorly that they have to buy their own debt in order to keep interest rates down? Does it suggest to you that the economic policies are right or that they refuse to acknowledge their own mistakes?

Sam the Man,

read this. It is superb in debunking these nitwits: http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/did-stimulus-really-destroy-million.html …. it’s called lying.

Sean,

Pimco has been short all the way down from 3.5%-plus to the current level below 3.2% in 10yr bonds. Fund managers can do this, traders cannot. Think about it, fund managers are actually ‘paid’ to be short. Lose money in a rallying market and ‘long’ funds make money anyway, but still underperform index. Their customers see +ve returns and don’t care so much, well not enough to change fund mangers at least, which is the important point. When the bond market tanks, you don’t want to post ‘the most negative’ return, and be kong & wrong. Pretty simple, and Pimco are simply wrong. They haven’t gone to school on previous episodes of QE, and are suffering because of it. and this, from the fathers of ‘new normal’.

Also, explain to me ‘….PIMCO, the world’s largest bond fund manager, estimates that 70% of the demand for US Treasuries is due to the US Federal Reserve. Hence the low interest rates (and the consequent impact on crowding out in other tradeable asset classes).”….

What’s that about? Most, including P…”default through inflation”…imco, say rates have not only performed contrary to the way the Federal Reserve would’ve hoped (no surprise, they didn’t peg the rate like they do the Fed Funds), but actually are betting on a complete diasaster for the bond market. And what crowding out? The analysis above (by Bill), plus our very eyes over the years, have (or should have) attuned us to the dynamic of falling rates as budget deficits increased. That’s what happens! If crowding out means lower borrowing rates, count me on board!

Other (risk) asset classes have a had a free ride since the inception of QE2, and a predictable timeline. The market is the market, and when it knows its funding side of the speculation equation is set, it will, well, speculate. So the idea that crowding out has occurred in other tradable asset classes doesn’t bear scrutiny. It was an invitation to speculate, and hope upon hope at the same time, that trickle down economics would actually work. Alas…. But what it does highlight is that you should be concerned more about the market’s ‘exit strategy’ from said speculation, than the Fed’s exit strategy. And it’s happening….

On Yen assets (read: JGBs), the Japanese have a trade surplus, and hence there is no real net demand for Japanese financial assets. The US, for example, is a different story. Persistent trade deficits create demand demand for US denominated financial assets. particularly from the peggers. Or is it really the other way around? Surplus countries to the US have a mecantilist trade motive, and hence accumulate USD assets as a result….

Bill “Budget deficits do this in two main ways: (a) they push up private savings; and (b) they push up corporate profits.”

-I guess the key issue is what are the consequences of private savings and corporate profits being pushed up? Does it result in people being more or less likely to do the things that lead to people being well provided for/content? Corporate profits should be a guide as to what should be done and what should be left undone. Corporate profits also lead to a transfer of power to corporations and their owners. Private savings influence behaviour not necessarily beneficially.

Sean

If the Japanese liquidate their savings then they are creating demand , and therefore, produces demand which produces taxes to the government, and reduces the Governments deficit.

If an international fund manager wants to take their money offshore, then let them. If enough money flows offshore, then the exchange rate will drop making the ecomony more competitive internationally. There will be some price adjustments, but the overall result is likely to be more economic activity, increasing tax revenues for the government and reducing their deficit. This robust economy will then attract people who wish to invest in real businesses because they are making a profit, and thus pushing the exchange rate up.

On the flip side, if they invest in new projects because there are no risk-free bonds to purchase then the economy will be better off if the new project increases the capacity of the economy.

I think that you missed my point on PIMCO’s motives. They have a profit motive to try and move markets in the direction that benefits them. I do not know what investments Bill has, but he is a tenured academic with security of income and therefore, no vested interest in making comments that could move markets in a direction that benefits him. Because of the size of PIMCO they only have to move markets small amounts to make large profits.

Neal

Sean

Is it right that we put people into/keep people unemployed because some else incorrectly believes that a Government may/will default on its debt. I say incorrectly, because there is absolutely no risk on the ability to pay as longer as the central bank can make up and down spreadsheets. There maybe a risk on the willingness to pay which is political decision.

Neal

to Bill Mitchell

What do you think of Serge Latouche’s theories for economic “degrowth”?

Is it possible to implement his views successfully? (you say MMT is not a policy, but the instrument to pursue it. Would it be possible to use MMT to achieve degrowth? I presume not, because the goal of MMT is to improve growth, not to diminish monetary incomes…)

“However, as the population ages, savings are liquidated for people to spend. This makes it harder for the Japanese Government is issue bonds to their domestic populace via the banks,”

No it doesn’t. Because if people spend, then it is taxed and the amount left to offset goes down. What Yen is left ends up in somebody else’s pockets which, surprise, surprise will then purchase government debt denominated in Yen because it pays a higher interest than the reserve rate.

In a sovereign nation like Japan it is best to view government spending as coming first, and ‘government debt’ as simply a savings account for what is left once all the private sector spending decisions have been made.

You might want to read a few more of the blog posts on this site so that you get to understand how monetary operations in a sovereign nation actually function. Otherwise you might end up with the notion that there is some sort of fiscal constraint on a sovereign nation when there clearly isn’t.

a little article about Pimco.

http://pragcap.com/pimco-versus-doubleline

Sean, an awful lot of economists let alone central bankers who failed to predict the mess we are in failed…and yet THEY haven’t been sacked.

Ratings Agencies say sovereign governments are risky yet gave AAA ratings to financial institutions that proved to be shall we say less than safe, have they been sacked?

“The next graph considers the relationship between the budget deficit (as a per cent of GDP) and the annual inflation rate in the US from 1931 to 2010. The annual CPI data comes from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (it is their annual series equivalent of the quarterly data used in the previous graph) and the The US Office of Management and Budget provide historical budget data back to 1930.

“The black line is a simple regression (indicating a slightly negative relationship – higher deficit, lower inflation) although I don’t wish to push the authority of that regression. It is just an indicator that has to be considered.”

I think that the x-axis on this and following graphs is mislabeled as budget deficit. The U. S. has run a deficit in only 9 years between 1931 and 2010 (inclusive)? It ran a budget surplus of more than 30% of GDP in one of those years? (I. e., a deficit of less than -30%).

If, indeed, the graph is mislabeled, so that negative numbers mean a deficit and positive ones mean a surplus, then the regression indicates a slightly **positive** relationship between deficits and inflation.

“If an international fund manager wants to take their money offshore, then let them. ”

That’s another term that is misleading. An international fund manager *can’t* take Yen offshore. Yen only ever exists at the Central Bank of Japan.

What the Fund manager can do is exchange their holding of Yen for holding of something else at the agreed rate for that exchange. Only the names of the owners on the Yen at the Bank of Japan changes. The amount of Yen doesn’t change by this process.

“According to this theory, if there is a rising budget deficit then there is increased demand is placed on the scarce savings (via the alleged need to borrow by the government) and this pushes interest rates to “clear” the loanable funds market. This chokes off investment spending. . . .

“The basic flaws in the mainstream story are that governments just borrow back the net financial assets that they create when they spend. Its a wash!”

To second what you are saying, when I read the first paragraph above, I thought, “But what about the effect of the gov’t spending?” (Or, equivalently, the effect of non-taxation?) The deficit is by definition the difference between gov’t spending and revenues. If you are examining its effect, you cannot take it as a given. When the gov’t runs a deficit it leaves money in the hands of savers/investors (instead of taxing it away), thereby increasing loanable funds by the same amount that it borrows. Right?

“My experience tells me that if a simple graph doesn’t support a relationship more sophisticated econometric analysis will not help much.”

“The best statistical test is the interocular traumatic method: It hits you right between the eyes.”

— L. J. Savage

(Quoted from memory from a small pamphlet Savage gave me. I don’t think it was published.)

Since Bill brought up the matter of the IMF Chief, thought the following article might be of interest over at Ives Smith blog:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/05/imf-chief-strauss-kahn-arrested-for-alleged-sexual-assault.html

Saturday, May 14, 2011

IMF Chief Strauss-Kahn in Custody for Alleged Sexual Assault (Updated)

I’m not easily astonished, but this qualifies. From the Wall Street Journal:

“In between the two pieces quoted is a rail against “Keynesians” – like “Austrian economists like F.A. Hayek predicted the Great Depression when the Keynesians said that the economy was fine”. As an historical note, there were no Keynesians at the onset of the Great Depression. This historical reinvention by Mullen permeates his whole article and his book – A Return to Common Sense: Reawakening Liberty in the Inhabitants of America.”

Exactly!!!

Sean: PIMCO has decided to shift their investments away from US Treasuries into other securities with a safer fiscal and monetary policies.

Jeff Gundlach of Doubleline, which is beating the pants off PIMCO, is on the other side of the trade.

@Sean

I think you have missed the point with PIMCO/US bonds. Federal Reserve, as a deliberate policy move, chose to buy bonds. Most commentators (plus me FWIW) assumed that they were trying to force down rates elsewhere on the curve because they had nowhere else to go on the overnight rate. Fed intervention has actually resulted in higher yields not lower ones (which to many, including me is counter intuitive). PIMCO at the time were reported as saying that bonds were a bubble, so they got out. None of that has anything to do with fiscal and monetary policies. If we want to go my expert vs your expert, another billionaire, Stanley Druckenmiller is long bonds (for reasons that most in this comment thread would disagree with BTW).

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703864204576317612323790964.html

@William Wilson

Call me a cynic. But I’m not convinced at all. Why should DSK a know womanizer with a lot of different means to seduce women suddenly turn into a violent rapist? Also one thing DSK isn’t exactly known for is to be a lunatic. Only a crazy would rape a woman and the other minute have relaxed lunch in the same town with his daughter. So for me DSK isn’t guilty until convicted. And I agree with yesterday’s Le Monde editorial: “When one of the world’s most powerful men is turned over to press photos, coming out of a police station handcuffed, hands behind his back, he is already being subjected to a sentence which is specific to him.”

@Stephan

Seduction and violent subjection are two different things that are not related.

DSK has a long history of woman’s aggression but none dared to complain until now.

BTW, the defense is already starting to plead “consensual” sex when previously, he denied being there at all.

So NYPD has forensic evidences that place him on the premises with the victim.

I’m very glad they caught him.

Will be glad if he is punished.

This doesn’t stack up exactly.

No Austrian will claim that Money supply is the only variable on inflationary pressures. The productive increases in China have had a deflationary effect on prices globally. Therefore the argument against the Austrians appears to be fabricated.