I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Distorting history to appear progressive

In a blog last week – These were not Keynesian stimulus packages – I considered the trend among faux-progressives to invoke Keynes as their mentor as they advocated or were cutting back public deficits in a pro-cyclical manner. That is, they were proposing to cut back deficits just when they should be providing strong support for aggregate demand in the context of weak demand. The specific discussion was focused on a recent Australian Fabian Society essay (April 11, 2011) by the Australian Treasurer Wayne Swan – Keynesians in the recovery. There are two points I want to revisit in regard to this paper – one specific and one general. Both points demonstrate that the fiscal strategy of the Australian government is based on a false premise and that they are selling that strategy by distorting the historical evidence.

But first an aside.

I will have to be careful with my use of the term “mainstream macroeconomics” and “mainstream macroeconomists” by which I have meant the overwhelming proportion of my profession that extols the virtues of alleged “self-regulating markets”, a view that is built on a thoroughly inapplicable view of the way the monetary system operates. The “mainstream” think a currency-issuing government is like a currency-using household only bigger – a super household if you like.

They then build a logic that is used to attack public deficits as dangerous that is nothing short of a fantasy world.

But things have changed recently. Apparently, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) which I clearly write about is now mainstream too. This article (April 8, 2011) – Why Gold and Silver Will Go Higher – purports to give advice to investors. My advice to the investors who might read this stuff is – delete the page from your bookmarks.

The article was talking about how the US government wasn’t the slight bit interested in reducing their deficit and:

… the whole dollar system is a sham now built on Ben Bernanke’s ability to push buttons on a computer.

No sham, just a fiat monetary system. The government is the currency issue and most issuance is done electronically even though I doubt Ben Bernanke is the officer that is engaged in the specific central bank operations that credit and debit bank accounts in the private banking system on behalf of the government.

Then (in horror at the US government having this capacity) the article said this:

But what most people don’t know is that there’s a whole, mainstream school of economics that actually believes that deficits don’t matter. Not now, not ever. Deficits, they say, simply cannot bankrupt a country with the power to print its own currency. They’re called neo-Keynesians or Chartalists, or proponents of Modern Monetary Theory.

These people hold enormous sway in the Federal Government, and their theories give tacit approval to the Federal Government to do what it will.

I looked up my diary over the last few years to check how many meetings I have had with US government officials. Answer: None although some E-mail correspondence. The resulting policies do not resemble the advice I gave in those E-mails.

So I am guessing that Warren, Randy, Scott, Randy, Pavlina et al (my US MMT mates) are living it up in Washington – Government gurus … the thing is they haven’t told me that. Maybe they are holding out on me for a top job in Wall Street because they are influential intellectuals who “hold enormous sway in the Federal Government”. There is plenty of corruption money to share around guys (generic) – that is what being mates is all about.

Ridiculous!

Anyway, back to the theme today – the way the Australian government is behaving – which generalises to how the G-20 Finance ministers are behaving (more on their lunatic output overnight tomorrow – I think!).

Historical distortions

Recall that the Australian Treasurer said the following:

… if we are going to be Keynesians in the downturn, we have to be Keynesians on the way up again. That means a speedy return to surplus.

The political reality that is he addressing is that the Federal Labor government is losing credibility as a progressive force in politics. Their constant neo-liberal macroeconomics mantra clearly runs counter to what “progressives” think is a reasonable demonstration of responsible government although there is no clearly laid out guide to that from the majority of “left” inputs.

But one theme seems to resonate and that is that progressives think Keynes was “good” and stood for something they can identify with – government intervention etc. Most of the progressives also think it is reasonable to expand the deficit in bad times and cut it in good times – the balanced budget averaged over the course of the business cycle idea – although when you probe that view it is clear they do not understand the implications of that rule for the other sector balances.

There is total ignorance in fact demonstrated when you put it to these “deficit doves” that a nation with an external deficit will on average over the business cycle force the private domestic sector into deficit of the same magnitude as the external deficit if the government actually balanced their budget over the same cycle (on average).

They also cannot appreciate that this would mean that the private domestic sector would be accumulating ever increasing levels of private debt – the exact dynamic that led to the global financial crisis.

The smarter ones then talk about export-led growth – probably after reading some IMF paper – to which you ask: (a) how will that occur? and (b) why would you want to deny your citizens of net imports from abroad? The answers are never acceptable.

Anyway, for the public debate all this essential understanding amounts to “too much detail” and so the Treasurer can get away with this loose association with Keynes as a way of appealing to the cohort that their policies are alienating.

In the blog last week I showed how the policy stance adopted by the Government in the downturn was hardly one that Keynes himself would have proposed. But what about the approach in the upturn – to speedily introduce harsh fiscal retrenchment. Well first you have to an upturn strong enough to support growth sufficient to ensure full employment.

On Saturday (April 16, 2011) the ABC carried the story – Massive budget cuts expected in May.

The story noted that:

Confidential Treasury figures showing a $13 billion fall in economic growth this financial year are expected to force drastic cuts to the Federal Government’s May budget.

The Federal Treasury is expected to again revise down this year’s economic growth figures because of weaker-than-expected consumer demand.

Okay, here is a question that any Economics 101 student should be able to answer.

Q: Given that economic growth is slowing because of “weaker-than-expected consumer demand” and net exports are providing a negative contribution to growth overall, what should the government do to protect national income and employment growth?

A: (by some sensible and educated student) The government should attempt to offset the negative growth contribution coming from private spending by increasing public net spending.

Teacher assessment: 100 per cent correct.

Australian Treasurer response (as gleaned from the quote above in his Australian Fabian Essay): Keynesians in the downturn – increase deficits.

Teacher assessment: 60 per cent correct and the extra marks would have been given if you had have said that you would use the increased deficit spending to target employment via direct job creation.

Australian Treasurer answer (as reported by the ABC news story):

“These are impacts in the short term and there’s no doubt there will be an impact on the budget bottom line this year … But as we go into the forward estimates, as we go into the years ahead, growth will be strong. Short-term weakness, medium-term strength.

The Treasurer who is now at the G-20 meeting expanded on this line to journalists in Washington:

JOURNALIST: Why then if there such a big hit to the economy is it so important to return to that surplus right on target [inaudible]?

TREASURER: … both in the medium-term we’ll be strong. The mining boom and the investment pipeline that comes with that will mean that growth will be strong. Unemployment is already low, so by 2012/13 our economy will be approaching capacity. So what we have is an impact on growth now and an impact on Government revenues … What we must ensure we do is come back to surplus in 2012/13, because by then our economy will be at capacity and it’s very important to make room for the private sector.

JOURNALIST: The Government made a promise to get back to surplus by 2012/13 before … they will affect Australia’s ability to get back on time?

TREASURER: These are impacts in the short-term. There’s no doubt there will be an impact on the budget bottom line this year. But as we go into the forward estimates, as we go into the years ahead, growth will be strong. Short-term weakness, medium-term strength.

At present there are at least 12 per cent of productive labour resources in Australia that are idle – either unemployed or underemployed. The concept of making “room” for the private sector because we are approaching capacity makes a farce of the Treasurer’s concept of “full capacity”. We are no where near full capacity even though a few regions are booming.

Further, the point that the Treasurer ignores is that economic outcomes are not discrete independent events. Expectations and sentiment link decisions to spend by players in each sectors and outcomes become interdependent.

The Treasurer is assuming that the sharp fiscal contraction – now being marketed in the media as “drastic cuts in the budget in May” – will have no lasting negative effect on private sentiment.

The other major mistake he is making is that the slowdown is all seasonal and driven by the natural disasters that have beset our nation and wider region in the last 5 months or so – cyclones, floods, earthquakes and tsunamis. Clearly these disasters have had a negative impact but consumer spending was slowing well before the disasters and output growth started to slow in lock-step with the declining fiscal stimulus.

Unfortunatel for us Australians, the response by the Federal Opposition’ was about as lame as the Governments to the slowdown. Their leader said:

We wouldn’t have wasted the money that this government has wasted. If the Government had been tough on itself it wouldn’t have to be tough on the Australian people at the upcoming budget.

Well if the Government had have followed the advice of the Opposition and not provided the stimulus they did then the Australian economy would have gone into an drawn out recession – perhaps not as bad as in the US and the UK but much worse than our recent experience demonstrated.

So the cyclical deficits would have been bigger and the real economy would have been in much worse shape with a longer recovery period ahead. Unemployment would have risen to the forecasted 8 or so percent (estimated at the beginning of the crisis).

Please read my blog – Fiscal policy worked – evidence and Fiscal austerity is undermining growth – the evidence is mounting and Tick tock tick tock – the evidence mounts and US fiscal stimulus worked – more evidence – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that fiscal policy in Australia is now deliberately becoming pro-cyclical as it is in the UK, the US and the Eurozone and elsewhere. Economists long

Now, lets go back to the Treasurer’s Fabian essay. In justifying the intellectual lineage of the position of the current government (that is, to run pro-cyclical fiscal policy) he appealed to history and the approaches taken by some of the famous Treasury heads.

By way of summary, Swan said that the policy environment in Australia under the various Labor Governments dating back to the Great Depression:

… that was to guide the emergence of Australia as a 20th Century social-democratic state: demand management in pursuit of full employment and rising prosperity through balanced budgets over the economic cycle.

First, the Hawke-Keating Labor government (1983-96) clearly abandoned the commitment to full employment. They oversaw persistently high unemployment and set up a wages policy that led to dramatic cuts in real wages both absolutely and relative to productivity growth. The wage share in national income fell sharply during the 1980s under this Labor government. They refined the neo-liberal approach to macroeconomic policy in Australia.

Second, what about this idea that historically federal governments have “balanced budgets over the economic cycle”. This was just a single line in his speech but an extremely important part of his claim that the current Government is Keynesian and that now is the time to cut back and push for surpluses – to average out in balance over the cycle.

No-one in the media (as far as I know) has actually challenged that depiction of our past. The myth remains that responsible governments “balance their budgets over the business cycle”.

Well that would mean that for as long as we can get data, successive Australian governments have been grossly irresponsible. The reality is that budget deficits have been the norm over any of the successive business cycles. There is no evidence that Australian governments “balance budgets” over the cycle.

The further evidence is that as the neo-liberal persuasion has become dominant in macroeconomic policy, Australian governments have attempted to run discretionary surpluses. The outcomes of this behaviour have not been good and overall this period (since around the mid-1970s) have been associated with lower average real GDP growth and more than double the average unemployment rate.

To probe this point a bit further I played around with some data pertaining to budget and national income outcomes. I compiled a dataset frmo 1953-54 to 2010-11 (that is, fiscal year data) from two sources. The earlier data (1953-54 to 1970-71) is from the historical publication by R.A. Foster and S.E. Stewart (1991) Australian Economic Statistics, 1949-50 1989-90, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney.

The second time series (1970-71 to 2010-11) is from Statement 10 which is the data appendix to Budget Paper No. 1 published by the Commonwealth Government when it delivers its annual budget.

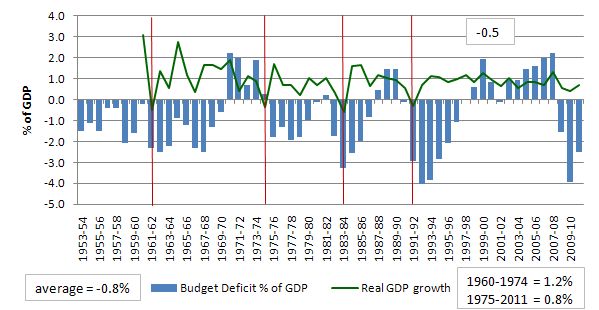

There are some issues about combining this data set and with each individual data set. But in general the graph below is a reasonably reliable depiction to the history of Federal Government Budget outcomes over this period. The columns show the Federal Budget balance as a per cent of GDP (negative denoting deficits) while the green line shows the average quarterly real GDP growth (averaged over the financial year at June).

The red vertical lines denote the trough of the respective business cycles. So the real GDP growth line approximates where in the year the negative real GDP growth manifested. But for our purposes it is near enough.

The upper numbers in boxes are the average deficits over each cyclical periods. The average deficit over the whole period was 0.8 per cent of GDP. The average real GDP growth per quarter from 1959-60 was 1.2 per cent and after 1975 this dropped to 0.8 per cent. The unemployment rate averaged below 2.0 per cent in the pre-1975 period and averaged around 5.5 per cent after 1975.

The 1975 Budget was a historical document because it was the first time the Federal Government began to articulate the neo-liberal argument that budget deficits should be avoided if possible and surpluses were the exemplar of fiscal responsibility.

Some points to note:

1. One the rare occasions the budget was pushed into surplus (usually by discretionary intent of the Government) a major recession followed soon after. The association is not coincidental and reflects the cumulative impact of the fiscal drag (that is, the surpluses draining private purchasing power) interacting with collapsing private spending.

2. There is no notion over this period that the budget outcome was “balanced” over the business cycle. The historical reality is that the federal government is usually in deficit. If I had have assembled more historical data which is available in the individual budget papers going back to the 1930s then it would have just reinforced the reality that surpluses have been rare in our history independent of the monetary system operating (the old convertible system or today’s non-convertible system).

The fact that the conservatives were able to run surpluses for 10 out of 11 consecutive years (1996 to 2007) is often held out as a practical demonstration of how a disciplined government can run down public debt and provide scope for private activity. The reality is that during this period we have witnessed a record build-up in private indebtedness.

The only way the economy was able to grow relatively strongly during this period was that private spending financed by increasing credit growth was strong. This growth strategy was never going to be sustainable and the financial crisis was the manifestation of that credit binge exploding and bringing the real economy down with it.

Did Keynes advocate balanced budgets over the cycle?

The other part of the Treasurer’s story is that Keynes advocated balanced budgets over the course of the business cycle. Is that true?

Researchers go back to Keynes 1924 Macmillan publication – A Tract on Monetary Reform – where he argued strongly that price stability was a policy target and this including avoidance of deflation. This was in the context of nations being reluctant to allow their pegged currencies to depreciate which would have provided in Keynes’ assessment high employment. At the time Britain languished with high unemployment and Keynes began to articulate a view that not only was the reluctance to depreciate undermining employment growth but also that the government should use fiscal policy (via direct job creation in public works) to reduce unemployment.

I won’t consider in this blog the arguments that Milton Friedman (and the long line of Monetarists that followed him) made that the Tract was really the first Monetarist statement. That is a complex argument and I might write a separate blog on that if there is interest.

As Keynes’ view unfolded over the bleak 1920s in Britain he did argue that governments should run deficits when private spending declined and reduce those deficits when future growth was strong enough. The intent was that the budget was to be more or less balanced over the business cycle.

He never argued that governments should start cutting back deficits now and create surpluses just in case private spending growth is strong in the future. He readily understood how pro-cyclical policy would undermine private confidence.

In the context of today, with private spending still weak, notwithstanding some evidence that private investment might strengthen over the next few years, Keynes would worry about the negative consequences of a further weakening of aggregate demand and national income generation arising from a harsh fiscal contraction.

Further, in the context of the time, the classical economists (who Keynes’ discredited) advocated balanced budgets each year – the sort of rules that are now being discussed by conservatives.

So Keynes was reacting to that and noted that such a rule would be inflexible and damage the chances of the economy achieving full employment.

His view was that budgets might be balanced over the business cycle if that was consistent with full employment. He also favoured running balanced budgets on the recurrent (operational) budget – that is, consumption spending and allowing the capital works budget to vary over the cycle. This was consistent with his view that the principle fiscal intervention should come from regionally-targetted public works schemes aimed at maximising the employment dividend from the fiscal outlays.

The capital budget would be the vehicle for balancing over the cycle if that was appropriate.

If you examine the current government policy and its proposed fiscal retrenchment you will not see that sort of approach being adopted. I will comment more on that when the actual document is delivered in May 2011.

But Keynes would never has agreed to the blind administration of a fiscal rule of the type the Australian government is pursuing. He would never have agreed to “forward-looking” pro-cyclical fiscal policy.

Further, much of the smoothing out of demand over the cycle (which is really what the “balanced budget over the cycle” is about) was seen to come from the cyclical component of the budget. The Australian government is manipulating the structural component to attack the cycle – that is the worst thing you can do.

The reality is that if we truly measured the current budget stance at a properly calibrated full capacity benchmark we would find the structural component is already close to balance and by the time the Government has finished its so-called Keynesian adjustments the budget will be very contractionary.

Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

Of-course, the “Keynesian position” is rejected by those who consider functional finance to be a better approach to fiscal management. Functional finance underpins MMT.

Please read my blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

As I explained in this blog – The full employment budget deficit condition – the goal of fiscal policy is to ensure there is full employment. Whether that requires a deficit or a surplus in any particular period is neither here nor there.

The fact is that the budget outcome should never be the goal of policy. The goal should be to maximise real outcomes and maintain price stability. The problem is that in elevating the budget outcome to the centre stage and setting artificial rules, governments are very likely to damage prosperity.

And, undermine the achievement of their rules anyway – automatic stabilisers oblige!

That is enough for today!

I love it when I can predict where the MMT blogs are heading with their analyses. I picked yours and recessions and I note in your graph each and everytime there was a surplus (even a small one) there was a recession. I also did it earlier today with (not quite MMT) Edward Harrison and his Too Much Finance post at CreditWriteDowns. It helps that I was doing a write-up for the Wiki on Recessions & Depressions last night.

I think typically people can’t separate a third school of thought into their typical thinking of Monetarism & Keynesian (duality) & what us Functional Finance advocates say doesn’t fit into either school, so they dismiss the content of the argument as unreliable since it is not in the popular media.

I like the way James K. Galbraith puts it, the result of a budget is an outcome not a policy tool or words to that effect.

don’t let this “enormous sway” you have within the corridors of the Federal Government go to your head…..

Bill, Another argument that can be cited to back your argument (which I’ve mentioned before on your blog) is thus.

Assuming the monetary base and national debt are to remain constant relative to GDP, they will have to be constantly topped up via deficits to take account of 1, inflation (say 2%), 2, population growth (say 2%) and 3, increased output per head (say 2% a year). So if we assume the debt plus monetary base are 80% of GDP (to take a not totally unrealistic figure), then the deficit needs to be 4.8% of GDP EVEN WHERE GOVERNMENT AIMS FOR A NEUTRAL STANCE, i.e. one which is neither stimulatory nor deflationary. (2+2+2) x 0.8 = 4.8. (The U.S. monetary base actually expanded by about 7% a year in nominal terms in the 20 years leading up the credit crunch, so my above very rough back of the envelope calculation isn’t too far out.)

The above point could be used to trip up deficit terrorists, U.S.Republicans and other forms of low life, as follows. Since horizontal money nets to nothing, the only “real money” is in a sense vertical money. In the absence of the above “deficit even at neutral stance”, the amount of this real money per head will eventually shrivel to nothing. So the question for the above “low life” is this: do you want the amount of real money per person to eventually to shrink to nothing?

Of course the question is fifty miles above their heads, so it’s probably silly question. But it’s a nice though (especially as I thought of it).

Net Government spending is one symptom/signal/gauge of the economic temperature.

Bill,

Regarding MMT’s “enormous sway” and sinister power in Washington.

It was bound to happen. As MMT chips away at the neoliberal edifice, two kinds of sparks will be struck. There will be a few public intellectuals and journalists who see the real world suddenly, if briefly, illuminated. But for every one of these, there will be at least two (probably more like ten) who will see in that spark only a reflection of their own fervidly imagined nightmare scenario.

America is rife with end-timers, with most foreseeing imminent hyper-inflation and national bankruptcy. We will all live in tents and cook our gruel over a campfire in discarded number-ten cans. For fuel, we’ll use the worthless bundles of hundred-dollar bills dropped from Ben Bernanke’s black helicopters. After breakfast, we’ll strap on our second-ammendment remedies and march to Washington, where we’ll restore the republic – with a Balanced Budget Amendment and a permanent restoration of the Gold Standard.

Between them, the corporatist Democrats and the Tea Party lunatics are getting ready to plunge America back into recession if they can manage it. They have pulled off the austerity bait-and-switch maneuver. With no honest or meaningful opposition in the corporate media, they are about to justify big cuts to public services accompanied by yet more public-sector layoffs by saying “at least we preserved Social Security and Medicare for a *few* people”.

America will see two more years of (at best) stagnation. Probably many more. This feels more like a depression every day, with more and more depression-spawned trolls coming out of the woodwork. As Upton Sinclair wrote, “When fascism comes to America it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.” But now comes news that Glenn Beck is being dropped by Fox News for being such a constant embarrassment. (Gee… they can actually feel embarrassment?) And a wave of grass-roots protest has rocked the old union stronghold of the upper midwest. Sarah Palin came to Madison the other day and couldn’t draw a crowd big enough to outnumber the counter-demonstrators. So maybe we’re turning a corner of some kind. Even if we are, we face a brutal uphill fight.

Anyway, thanks for everything you do, Bill. If we can hold onto our sanity long enough, what is rational will ultimately prevail.

Cheers

The link between government surpluses and recessions is not that clear from the graph: there are recession without a surplus and surplus without recession.

It would be interesting to plot government balance + external balance to see what happens around recessions.

The ALP is failing in a futile attempt to hold onto power. The much vaunted investment in mining. What is that exactly? The new gas fields 11bn or so? leasing iron ore rights to the Chinese? More brown coal in Victoria? Way to go, selling the countries assets to foreigners for peanuts..what a strategy, remenisent of the Congo in it’s heyday.

At the same time investment in commercial and private property is looking decidely toppy. Lessons from US,UK and Ireland not learned. The Current account is not looking like it’s going into surplus any day soon.

Using Bill’s handy dandy sectoral accounts analysis. The prognosis doctor please…….”the economy is basically screwed, nowhere to go, but might stagger along for a few more quarters.”

Is it all a cunning setup to hand power to liberals, whose spending cuts will collapse the housing market and make them unelectable for a generation.

MamMoTh, the link looks clear enough to me, the only one that it doesn’t explain is 1961. Like you, I assume it was caused by adjustments to the external balance and Menzies credit squeeze budget.

Senexx, it doesn’t explain 1961 and 1983 I’d say, nor the absence of recession in the 2000’s.

So it’s neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition, which means you cannot infer anything.

I guess adding the external sector balance will give a much more clear picture.

Much more interesting is the correlation between the rate of change of the change of the debt level of the private sector with GDP growth (see Steve Keen’s work).

Bill –

No, merely one of the conditions that led to the GFC. But increasing levels of private debt are a sign of private sector confidence, which is a good thing. The GFC was caused by banks lending to people who were unable to service their debts, but there’s no reason at all why increasing private debt has to involve that.

And continuing to run deficits instead of surpluses would not have prevented the GFC at all. Indeed it would have exacerbated its effects, as it did in Britain.

Even the correct answers???

The obvious answer to (a) is by producing the products that customers overseas want to buy. What’s unacceptable about that?

As for (b), the obvious answer is that there are no advantages of net imports. Imports do benefit us – but so do exports because the money we get for them exceeds what it costs us to produce them. And without net imports our currency will decline, increasing commodity prices and therefore putting up inflation.

Except that it isn’t pro-cyclical at all. And I’m rather concerned that you’re looking at it in isolation. Some months ago you wrote that use of fiscal policy was a better tool to control inflation than interest rates were. I believe you are right, and therefore the two should be looked at together. A surplus with low interest rates is better than a deficit with high interest rates.

1961 was not a modern money system and in 1983 the system was in transition from fixed to floating exchange rates.

Next.

.. also I think there was a slight rise in Unemplyment in 1961 which nearly cost Menzies an election (Commie prefs got him over the line I think).

Alan, lol! That’s still 1 out of 3. Neither a necessary nor sufficient condition.

Next.

MamMoTh,

The accounting identity “NAFA = DEF + BP” is true whatever monetary system one speaks of.

“…surpluses have been rare in our history independent of the monetary system operating ….” (from the main post)

(The graphs looks inverted though, a negative deficit is a surplus)

Thanks Ramanan, that’s the point I was about to make, and if you take into events from 81, it quite easily leads to the 83 recession. Just like the American Surpluses in 2000s leads to the American Recession now.

The small deficit in 2000s explains the lack of a recession in Australia. It also suggests that we’re trying to export our way out of the situation (which I’m guessing is also what we tried in 61 until demand collapsed).

I would also say we’re in a recession in Australia (for the same reason + GFC) now which we’re just beginning to recover from as Bill’s recent Labour Force post indicates (the general public and media deny this since it wasn’t a media defined technical recession).

Surpluses force the non-government sector to use their savings and once they run dry they resort to credit.

Therefore, the negative impact of the surplus will take a little while to kick in.

Household debt via credit in Australia has gone through the roof as a result of the libs running surpluses when excess capacity exists.

Governments running surpluses when the economy is nowhere near full emplyment are relying on the non-government to spend via credit to drive growth.

The government does not have a budget constraint in terms of its own money but households certainly do.

Strangely enough the ne0-liberals think that households should run deficits and the government should run surpluses.

Hence, rejecting government deficits when excess capacity exists is advocating pushing households into a cycle of unsustainable spending via credit.

next.

Alan Dunn –

What makes you think it wouldn’t have done so anyway? It did so in Britain when the government was running deficits.

Aidan,

It’s all in the national accounting identities.

And given that the current account is always in deficit:

a government surplus = a non-government deficit.

If you could provide a link to the data / years you are referring it would be interesting.

Alan Dunn says:

No it isn’t. National accounting identities don’t force people to save!

What is the basis of that assumption?

But it doesn’t commute – they could easily both be in deficit.

I’m referring to the early 21st century, up until the GFC.

Aidan,

“a government surplus = a non-government deficit.

But it doesn’t commute – they could easily both be in deficit.”

No they can’t. Otherwise they wouldn’t sum to zero.

Remember that ‘non-government’ includes both the domestic private sector and the external sector.

Aidan,

Australia’s current account has been in deficit for a very long time – and similar is also true for many other developed nations.

This is a fact not an assumption.

When the government runs a deficit the non-government have a choice to save while maintaining their existing standard of living or they can improve their standard of living ans save less or nothing at all.

If the non-government want to increase their living standards even more then they can seek to spend via credit.

In the case of a government surplus the non-government needs to seek credit just to maintain their current standard of living once their savings have expired.

We could complicate things by talking about productivity gains but that’s pointless when we consider that the gains are skewed towards those that own the means of production rather than those operating it.

Take a look at how income shares for owners (profits) are increasing at a much faster rate than real wages are for workers if you have any doubts.

cheers.

Alan Dunn says:

That’s not an assumption, it’s an oversimplification. According to http://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/balance/1005-trade-balance.png although most of the time it’s in deficit, it has recently been in surplus.

You seem to be describing the household sector, but the business sector operate quite differently. It doesn’t care about standard of living. It borrows when it thinks it can make a profit from doing so. And under normal circumstances availability of credit is not a significant constraint. And as long as there’s a profit to be made, businesses desire to borrow more whether or not more is being saved.

I didn’t have any doubts before I saw the graphs at https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=13193 but now I suspect it’s largely an American issue and doesn’t have much relevance to the Australian situation.

Aidan,

The current account is the sum of the balance of trade, factor incomes, and cash transfers.

You only posted the balance of trade data.

Therefore, what I previously said still stands.

Aidan,

The relevant ABS dataset is 5302.0 – Balance of Payments and International Investment Position, Australia.

http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/meisubs.nsf/0/586A3A0EAF3965DDCA25784500156B3E/$File/530201.xls

Alan Dunn “rejecting government deficits when excess capacity exists is advocating pushing households into a cycle of unsustainable spending via credit.”

I think aggregating the whole non-gov sector together and then plucking a supposedly inevitable conclusion about households is mistaken. In the UK, hedgefund managers get paid by gaining assets corresponding to 20% of the the appreciation of the assets they manage. So as to avoid capital gains tax, they get living expenses by borrowing against that asset hoard rather than selling anything off. How could you claim that reducing the deficit by taxing those hedgefund assets would increase household debt? Asset price inflation or deflation is an enormous pool that can totally offset and overwhelm changes in household indebtedness. The sad fact is that banks will expand until defaults limit their size. Banks participating in a cycle of unsustainable spending via credit must be allowed to die, otherwise an even more outlandish cycle of unsustainable credit will follow.

“How could you claim that reducing the deficit by taxing those hedge fund assets would increase household debt? ”

I don’t recall ever making this statement or any reference to it.

Or is this hypothetical ?

Assuming you were asking me a hypothetical question rather than referring to something I did not say.

Why would I want to reduce the deficit if the economy still had excess capacity ? I wouldn’t.

Why would I want to tax the hedge fund assets ? Why not just change the rules ?

Example: In Australia I would abolish negative gearing quicker than I could blink.

“The sad fact is that banks will expand until defaults limit their size. Banks participating in a cycle of unsustainable spending via credit must be allowed to die, otherwise an even more outlandish cycle of unsustainable credit will follow.”

Absolutely. The rules need to be changed and lender of last resort type policies jettisoned.

Alan Dunn “Why would I want to reduce the deficit if the economy still had excess capacity ? I wouldn’t.”

-I genuinely fail to grasp the crucial part of MMT that is the heart of this. To me a deficit is taxation below the level of gov spending. What was baffling me was the concept that every conceivable type of taxation results in valuable excess capacity becoming idle. I used the hedge fund example as one potential type of taxation that I found impossible to equate with causing valuable excess capacity becoming idle. For you to say that deficits are helpful is equivalent to saying that every conceivable type of taxation would be unhelpful if it were sufficient to prevent a deficit. Otherwise you are saying that certain types of taxation are unhelpful rather than saying that deficits are helpful.