The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Are they all lining up to be Japan?

Everyone is lining up to be the next Japan – the lost decade or two version that is. It has been taken for granted that Japan collapsed in the early 1990s after a spectacular property boom burst and has not really recovered since. The conservatives also claim that Japan shows that fiscal policy is ineffective because given its on-going budget deficits and record public debt to GDP ratios the place is still in shambles. I take a different view of things as you might expect and while Japan has problems it demonstrates that a fiat monetary system is stable and we should be careful comparing Ireland, the US or the UK to the experiences that unfolded in Japan in the 1990s and beyond.

An article in the UK Guardian yesterday (April 11, 2011) – Is Ireland heading for a Japanese lost decade? – by Irish academic economist Stephen Kinsella claims that the when making a comparison between Ireland and Japan:

There are more similarities than differences in this story.

Kinsella says he is a “student of economic history” and has been reviewing “Japan’s lost decade” which led him to that conclusion. He acknowledges without explanation that “Of course the economies are different. Of course Japan had its own currency. Of course Ireland’s fiscal and political problems would be there regardless of Ireland’s banking disaster”.

I thought that was an interesting juxtaposition. Japan’s monopoly over its own currency issuance is a defining difference rather than one difference that can be easily compared to the similarities.

Further, Ireland would not have any fiscal problems if it had its own currency. It might has some real economic problems, as has Japan but they would be of an entirely different scale to those faced today by Ireland. Further, one might speculate that its political problems should be less acute had it stayed out of the Eurozone (that is, kept its own currency).

Japan’s lost decade has been vilified by the mainstream for years. The New York Times ran a special series last year – The Great Deflation – which purported to examine “the effects on Japanese society of two decades of economic stagnation and declining prices”. It was an interesting series but missed several key points.

Consider this Huffpost article (November 19, 2010) – Reconsidering Japan – from political analyst Steven Hill which addressed some of the “myths” about Japan that motivate economic policy debate in the advanced nations (such as the US).

In relation to the NYT series, Hill says:

Reading the series is about as cheery a task as rubbernecking at a car wreck on I-95. But unfortunately the Times series simply repeats the “conventional wisdom” about Japan put out by the same economic experts who missed an $8 trillion housing bubble in the United States, and in fact have been wrong on most of the big economic issues over the past two decades.

Look at it this way: In the midst of the Great Recession, the United States is suffering through nearly 10% unemployment and 50 million people without health insurance. A new report has found over 14% of Americans living below the poverty line, including 20% of children and 23% of seniors, the highest since President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. That’s in addition to declining prospects for the middle class, and a general increase in economic insecurity.

How, then, should we regard a country that has 5% unemployment, healthcare for all its people, the lowest income inequality and is one of the world’s leading exporters? This country also scores high on life expectancy, low on infant mortality, is at the top in literacy, and is low on crime, incarceration, homicides, mental illness and drug abuse. It also has a low rate of carbon emissions, doing its part to reduce global warming. In all these categories, this particular country beats both the U.S. and China by a country mile.

Doesn’t that sound like a country from which Americans might learn a thing or two about how to get out of the mud hole in which we are stuck?

The article is insightful and documents why the “you don’t want to end up like Japan” syndrome is appealing to conservatives but missed the point entirely.

According to Hill, during the lost decade, Japan maintained:

- An unemployment rate was about three percent and about half the US unemployment rate over the same period.

- Universal healthcare.

- Less income inequality than the US.

- The highest life expectancy among the advanced nations.

- Very low rates of infant mortality, crime and incarceration.

The obvious conclusion is that “Americans should be so lucky as to experience a Japanese-style lost decade”.

Hill attacks Paul Krugman who he says has regularly paraded the “lost decade myth” but misses the point that “Americans are the only ones who seem to think they need three refrigerators, four televisions and a car for everyone in the household” should be the norm to aim for and the benchmark upon which to judge economic success.

The Japanese are more collectivist in this regard as the metrics above suggest.

Krugman did write a column (March 9, 2009) in the New York Times – Japan reconsidered – which altered his usual “attack the dithering Japanese line”. Given the timing of that article and what has since transpired it is interesting to reconsider it.

Krugman said:

For a decade or so Japan’s lost decade has been the great bugaboo of modern macroeconomics. Economists constantly warned that you mustn’t do X or you must do Y, because otherwise we’ll turn into Japan. And policymakers congratulated themselves in advance for not being like their Japanese counterparts, who dithered and drifted, refusing to make hard decisions.

Well, I’m sure I’m not the only person to notice this: Japan doesn’t look so bad these days.

Which is one of the points I am making in this blog. On a number of indicators Japan held up in the face of a major collapse in private spending much better than other nations.

Krugman concluded that:

And given what the next couple of years are likely to look like, Japan’s lost decade – yes, growth was slow, but there wasn’t mass unemployment or mass suffering – is actually starting to look pretty good. We may or may not be about to face our own lost decade, but the sheer misery millions of Americans will face in the near future probably exceeds anything that happened in Japan during the 90s.

Which was a prescient look into the present!

But for Kinsella he still proposes to that the Irish government might learn from the Japanese experience to avoid a lost decade. Well if the Irish could replicate the Japanese response to economic crisis it would be far better shape than it is and will be for many years to come.

I thought some comparisons might put Kinsella’s mind at rest that Ireland is a lost cause while it remains in the EMU whereas Japan will always be able to avoid the dramatic decline in fortune that Ireland is undergoing because it issues its own currency (conservative central bank policy or not).

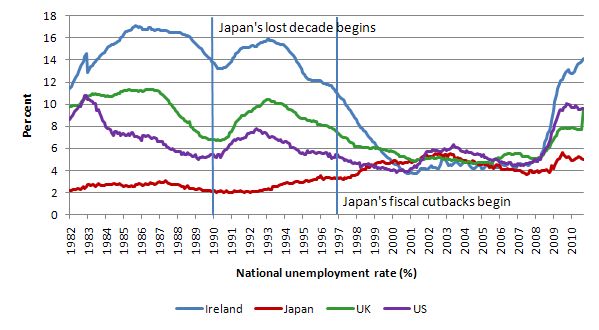

When comparing nations I usually begin with the real sector and focus on the events that affect people the most and nothing is more pervasive in that regard than unemployment. The following graph is taken from the OECD Main Economic Indicators and compares Japan to Ireland, the UK and the US from January 1982 to September 2010.

The two vertical lines note the beginning of the 1990s when the Japanese economy was seriously disrupted by the property collapse and 1997 when the neo-liberals badgered the national government into raising taxes because they claimed the budget deficit was dangerously high and the country was going bankrupt.

As we will see this sent the Japanese economy back into recession. But the scale of things is what matters. When Japan has a major real economic meltdown (pun not intended) the unemployment rate moves up – slightly. When Ireland encounters disturbed economic waters its unemployment rate soars.

Note the UK unemployment rate after fiscal austerity was announced courtesy of the national election result last year.

The point is that Japan’s lost decade was not that bad in terms of unemployment, which is an important measure of a nation’s progress.

The next graph shows annual employment growth from 1982 (Ireland’s MEI database is shorter). The vertical lines indicate the start of the “lost decade” and then the start of the 1997 austerity madness. Japan struggled to add net jobs in the early part of the 1990s. After several years of fiscal support, however, employment growth started to pickup again in the second half of 1996 and into 1997 it gathered pace.

Then it collapsed again as the fiscal austerity was imposed on a fragile economy. From March quarter 1998 to September quarter 2000 the employment growth rate was negative as the economy struggled as a result of the fiscal vandalism. It was only after a concerted renewed fiscal stimulus was introduced that growth slowly returned.

But even though the Japanese economy was in very serious trouble during the post-property collapse period in the early 1990s, annual employment growth was still mostly positive and in the four-quarters that it was negative the average annual growth was – 0.2 per cent – a very modest decline indeed.

Compare that to Ireland in the current crisis. From June 2008 to June 2010, the average annual employment growth in Ireland has been -5.5 per cent compared to Japan -1.1 per cent.

The reason lies in the inability of the Irish government to provide necessary fiscal support. Being a currency issuer really matters.

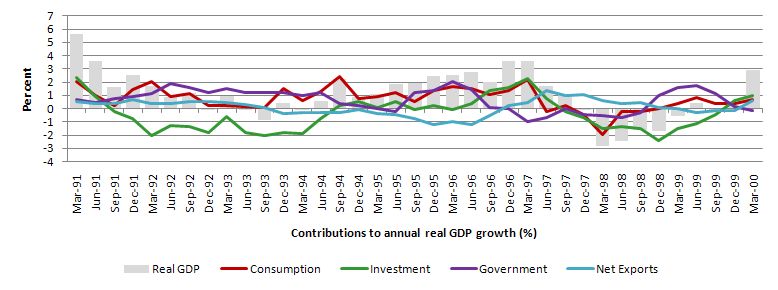

The following graph shows the contributions to annual real GDP growth by the major National Accounting expenditure components from March 1991 to March 2000 the period which saw growth stagnate in Japan. The data is available from Official Japanese statistics.

To compute the contributions to growth you use the formula Contribution = 100*(A(t) – A(t-1))/GDP(t-1), where A is the series you are interested in (for example, household consumption), t is now and t-1 is the time period in the past that you want to define the span of the growth by, and GDP is real GDP at the base period (t-1).

So for Japan, in March 1991, real GDP was 458,247.80 billion yen and household consumption (C) was 246,146.70 billion yen. In March 1992, the respective volumes were 466,052.40 and 255,489.60. So the contribution of to real GDP growth over that year from household consumption was 100*(246,146.70 – 255,489.60)/466,052.40 = 2 per cent. The fact that real GDP growth was only 1.7 per cent was the result of negative contributions from private investment (I) of 2.1 per cent; positive contributions from government spending (G) of 1.1 per cent; and positive contributions from net exports (NX) of 0.3 per cent. The contributions do not usually exactly add up to the GDP growth figure because of statistical discrepancies inherent in the National Accounts.

It is clear that there was a strong positive contribution from the government sector in the early years of the lost decade which attenuated the downward spiral in growth that was being driven by sharp declines in private investment and more modest decline in the contribution of net exports.

It was only when the Japanese government started to withdraw its fiscal support in early 1993 that the economy recorded on quarter of negative annual real GDP growth. Prior to that and after that the public spending supported the economy in the face of a very significant private investment collapse.

That is, until the neo-liberals won the political debate, albeit temporarily, and forced the cuts on the government in 1997. You can see that prior to that private investment was recovering under the wing of the fiscal support. After the austerity began and the contribution of government to growth became negative (from March 1997 but faltering in late 1996), both private investment and private consumption growth collapsed and were negative contributors to real GDP growth. Only net exports contributed positively.

At that point Japan experienced a full-blown recession with negative annual real GDP growth from the December quarter 1997 to March quarter 1999.

Growth returned in late 1999 once there was a strong positive contribution from government spending again.

Now consider the current crisis. The following two graphs juxtaposed with the same vertical axis for comparison show the contributions to annual real GDP growth for Ireland (left-panel) and Japan (right-panel) from March 2007 to December 2010. The Irish data came from the Ireland Central Statistics office.

The comparison is stark. Both nations entered as severe recession brought on by a private spending collapse. In Japan’s case it was worsened by its net exports sector also contributing negatively.

But consider the different way in which government spending behaves. The Japanese government spending started to play an increasingly positive role in stimulating growth and helped turn the economy into positive growth relatively quickly given the scale of the downturn.

The Irish government, one of the first to formally adopt fiscal austerity measures in early 2009 failed to provide the necessary support in the face of a collapse in private investment and consumption. The government contribution to annual real GDP growth became increasingly negative just at the time that sound fiscal management would call for it to make a positive contribution.

But the fiscal vandals argued that all would be well and private spending would fill the gap (and more). Ireland is still waiting and hasn’t come out of the recession yet while Japan has regained some private spending confidence and is growing steadily again.

Be careful in interpreting the net exports contribution to real GDP growth. In the recession, the decline in imports fell more quickly than the decline in exports which meant that net exports improved!

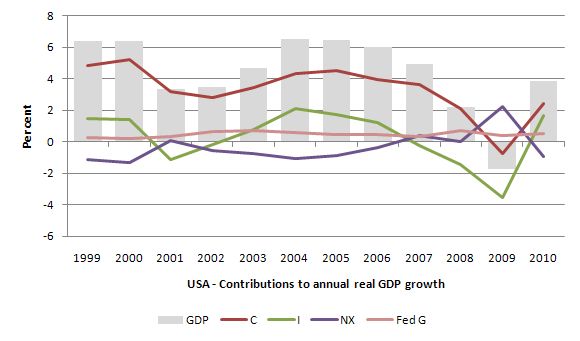

These historical snippets provide a firm warning to the nations now contemplating fiscal austerity. The following graph shows the contributions to annual real GDP growth for the US from 1999 to 2010.

The positive contribution of the US federal Government (Fed G) is clear in the face of collapsing investment and consumption spending. The dramatic cuts in the deficit proposed in the last week or so in the US will undermine real GDP growth. There is no question about that.

Conclusion

I am not suggesting that everything is fine in Japan. But in relative terms despite dramatic collapses in private spending, the Japanese government has shown a willingness to underpin collective outcomes and have kept unemployment from skyrocketing and employment growth from collapsing.

It can do this because it is a sovereign issuer of its own currency. Ireland cannot do this. The bank bailout situation is not the relevant issue even though the way the Irish government has handled that is appalling.

The problem is that those who are saying that the UK and the US are both on a track to be like Japan are, in my view, underestimating the magnitude of the damage the fiscal austerity will bring to those economies.

The relevant period to consider for Japan is between 1997 and 1999. Then the neo-liberals dominated and you can see what happened. In the other periods, there has been fiscal support – significant and necessary.

This public debate in the US and the UK at present is not considering this level of fiscal support. They are chasing Ireland down the path to obscurity by acting as if they have constraints on their currency issuing capacity and believing a bevy of mainstream economists who have told their respective governments that they are approaching insolvency.

Japan proves over and over again that a currency issuing government cannot become insolvent and that the public debt ratio can go to 200 per cent (well above the IMF 80 percent insolvency limit) and beyond without any problems at all. Inflation is low (and falling), interest rates have been low for 2 decades and unemployment remains below that experienced in most advanced nations – lost decade notwithstanding.

The reality for the US and the UK is they are heading Ireland’s way – despite having all the fiscal capacity they need to stimulate growth. If only Ireland could do that. For them, an exit from the EMU is required. For the US and the UK – bashing some sense into some conservatives (on both sides of politics) is all that is required.

That is enough for today!

This was an interesting? comment from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steven-hill/reconsidering-japanrecons_b_786198.html

“In Japan, if you are some freeter (slacker) who spent one hour handing out soapland flyers to people hanging out in Harajuku on one Sunday a month you are considered employed. Indeed, anyone who pays attention notices what a farce the Japanese unemployment rates always have been. The reality is double or maybe even triple the official figures.

Also, Japan has no social security system, something that blunts consumer spending as people save for old age.

I have lived and worked in Japan and I speak and read the language. The fear there is that it is devolving into a “karyuu shakai (low lifestyle expectations society).” This gets discussed more in the weekly magazines than it does in the government co-opted newspapers, but the fact is thaf Japan is dead in the water economically and has been for at least the last 17-18 years. Barely a day passes without some company announcing a “risutora” (mass layoffs through restructuring). There are growing homeless populations in major parks that used to be non-existent back in bygone days. Lifetime employment is a figment of the past, too, and that, coupled with massive corruption and institutional rigor mortis, has undermined the confidence Japanese have in their government and society.

The mistake that the Japanese government made was that their stimulus measures were half-a**ed and focused too much on the usual entrenched corporate interests. Doesn’t that sound familiar? “

I distinctly remember in the mid noughties at the height of the credit binge. There were many news articles bemoaning the lack of growth in Japan. They correctly diagnosed Japan was not doing enough to stimulate domestic demand. Unfortunately neo-liberal religion prevented them from administering the cure.

We have a situation akin to a Jehova’s Witness in emergency bleeding profusely. The blood transfusion needed to save him is against his religion.

“The reality for the US and the UK is they are heading Ireland’s way . . . ”

QE working in the U.S.?

To be sure, there is no proof that QE2 led to the stock-market rise, or that the stock-market rise caused the increase in consumer spending. But the timing of the stock-market rise, and the lack of any other reason for a sharp rise in consumer spending, makes that chain of events look very plausible. The magnitude of the relationship between the stock-market rise and the jump in consumer spending also fits the data. Since share ownership (including mutual funds) of American households totals approximately $17 trillion, a 15% rise in share prices increased household wealth by about $2.5 trillion. The past relationship between wealth and consumer spending implies that each $100 of additional wealth raises consumer spending by about four dollars, so $2.5 trillion of additional wealth would raise consumer spending by roughly $100 billion.

That figure matches closely the fall in household saving and the resulting increase in consumer spending. Since US households’ after-tax income totals $11.4 trillion, a one-percentage-point fall in the saving rate means a decline of saving and a corresponding rise in consumer spending of $114 billion – very close to the rise in consumer spending implied by the increased wealth that resulted from the gain in share prices.

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/feldstein33/English

For a more ‘critical’ view?

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2011/02/can-econometrics-distinguish-between-the-effects-of-monetary-and-fiscal-policy-during-the-crisis.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+typepad%2FKupd+%28Economist%27s+View+%28typepad%2FKupd%29%29

“anyone who pays attention notices what a farce the Japanese unemployment rates always have been. The reality is double or maybe even triple the official figures”

Damn, John, you beat me to it! Haha. I remember reading in ‘The Asian Financial Crisis and the Role of Real Estate’, a book published sometime ago, where a similar point is made. They argue if you used the comparable US standard unemployment is in fact double what the official figures say (see here, p. 85):

http://books.google.com.au/books?id=l4v6O4TzgPwC&pg=PA149&dq=real+estate+and+the+asian+financial+crisis&hl=en&ei=1i2kTfKVMYyKvQPR3qSDCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CD8Q6AEwAg#v=snippet&q=unemployment&f=false

So, yes, 4.1 % unemployment really means 8.2%.

Dear Mr Mitchell

I think that you make too much of employment. It is true of course that most people prefer having a job to being unemployed, as long as the job isn’t awful. Still, what matters economically is not employment but productive employment. In 1944, the US had full employment while 5 years earlier it still had a lot of unemployment. However, consumption was higher in 1939 than in 1944 because a lot of the jobs in 1944 were in the military and in the arms industry. In the case of Japan, a lot of jobs that were created since 1990 as a result of fiscal expansionism may simply be producing things or services that people do not need or want.

What is wrong with the jeremiads about Japan, however, is that it looks too much at growth. What matters is not how fast you are growing but how much you are producing. A rich country with no growth is still better than a poor country with a high growth rate, as long as the poor country hasn’t caught up. Despite its stagnation or slow growth, Japan was still the riches country in Asia from 1990 to 2010. People in slow-growth Japan weren’t leaving in droves for fast-growth China.

To illustrate this, let’s take Peter and Paul. Ten years ago Peter was making 10,000 a year and now 20,000 a year. Paul was making 80,000 ten years ago and still is making 80,000 today. Who had the better decade? Obviously Paul, despite his stagnant income.

The richer you are, the less you need growth. That’s why it is absurd to compare the growth rate of China with the American growth rate. China is still catching up. We should only compare the growtrh rates of countries that are at he same level.

Regards. James

Dear Spadj (at 2011/04/12 at 21:50) and John (at 2011/04/12 at 21:49)

No it does not. The OECD harmonised series compute the rates on common definitions with respect to the Labour Force framework.

You may say that there is considerable skill-based underemployment (in the service sector only) in Japan but the workers still get paid a full wage unlike the casualised time-based underemployed workers in most advanced nations.

best wishes

bill

@James Shipper,

“Still, what matters economically is not employment but productive employment.”

Isn’t there nothing less productive than an unemployed person? Or put it the other way, isn’t unemployment the biggest waste of all?

Employment by its nature has productive components to it. The individual experiences a degree of discipline, they are engaged in a setting where it is easier to change jobs relative to being unemployed, skills are sharpened/enhanced, etc.

If they are engaged in digging holes and refilling them, it is still superior to unemployment. Of course they should be involved in generating value, which is dependent upon their employer.

Tristan Lanfrey, “Isn’t there nothing less productive than an unemployed person? Or put it the other way, isn’t unemployment the biggest waste of all?”

-Someone employed to do counter-productive work is less productive than an unemployed person. Many administration jobs just create paper work that other people have to fill in at the expense of them being able to get on with useful work. Probably most of the FIRE sector jobs could also be put into that category.

There is clearly a bigger waste than unemployment, for instance people digging holes and filling them up for no reason.

John “the timing of the stock-market rise, and the lack of any other reason for a sharp rise in consumer spending, makes that chain of events look very plausible”

-I’m shaky on all of this. Isn’t it “primary dealers” ie banks who sell the bonds to the fed. The primary dealers are then left with bank reserves in place of the bonds. Do the primary dealers buy and sell equities between each other and so -by passing the bank reserves to and fro- push up equity prices? Why does having larger stocks of reserves and smaller stocks of bonds make them more inclined to buy equities? Do they think that if they have say $1B of long dated bonds then it is safe to hold $1B of equities but if they have $1B of excess reserves then that would make it safe enough to hold $2B of equities even though those equities are more over-valued and due for a correction? I could imagine a mechanism where companies can leverage up more cheaply (and so make equity more profitable) by selling corporate bonds at low interest rates because of reduced competition from treasury bonds. BUT since the start of QEII, treasury yields increased and yet equity and especially commodity prices nevertheless increased so much. Is QEII just a rhetorical “emperors new clothes” device and the markets bubble up because every one is smart enough to realize that everyone else is stupid enough to believe in the emperors clothes???

stone —

I think its correct that there exist some jobs that are net negatives for society. That said, not all “counter-productive” work will fall into that category. You need to account for the real but ill-measured consequences of unemployment such as the effect on children, the crime rate and the such.

D

Hi Stone,

This is from monetarist Tim Congdon re the UK economy.

“The intention of the Bank of England’s programme of quantitative easing is to increase the quantity of money by direct transactions between it and non-banks. Strange though it may sound, monetary expansion could occur even if bank lending to the private sector were contracting. In its essence the mechanism at work is very simple, that the Bank of England adds money to the bank accounts of holders of government securities to pay for these securities. (The details can be of mind-blowing complexity, but need not bother us now.) Roughly speaking, the quantity of money in the UK is about £2,000 billion. Gilt purchases of £150 billion over a six-month period would therefore lead by themselves to monetary growth of about seven-and-a-half per cent or, at an annual rate, of slightly more than 15 per cent. This is a very stimulatory rate of monetary expansion.

The objection is sometimes raised that the major holders of gilts are pension funds and insurance companies, and they will not “spend” the extra money in the shops. But the big long-term savings institutions are reluctant to hold large amounts of money in their portfolios, because in the long run it is an asset with negligible returns. At the end of 2008 UK savings institutions had total bank deposits of about £130 billion. They will be reluctant to let the number double, but – if the £150 billion were allowed to pile up uselessly – that would be the result.

What is the likely sequence of events? First, pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds and so on try to get rid of their excess money by purchasing more securities. Let us, for the sake of argument, say that they want to acquire more equities. To a large extent they are buying from other pension funds, insurance companies and so on, and the efforts of all market participants taken together to disembarrass themselves of the excess money seem self-cancelling and unavailing. To the extent that buyers and sellers are in a closed circuit, they cannot get rid of it by transactions between themselves. However, there is a way out. They all have an excess supply of money and an excess demand for equities, which will put upward pressure on equity prices. If equity prices rise sharply, the ratio of their money holdings to total assets will drop back to the desired level. Indeed, on the face of it a doubling of the stock market would mean (more or less) that the £150 billion of extra cash could be added to portfolios and yet leave UK financial institutions’ money-to-total-assets ratio unchanged.

Secondly, once the stock market starts to rise because of the process just described, companies find it easier to raise money by issuing new shares and bonds. At first, only strong companies have the credibility to embark on large-scale fund raising, but they can use their extra money to pay bills to weaker companies threatened with bankruptcy (and also perhaps to purchase land and subsidiaries from them).

In short, although the cash injected into the economy by the Bank of England’s quantitative easing may in the first instance be held by pension funds, insurance companies and other financial institutions, it soon passes to profitable companies with strong balance sheets and then to marginal businesses with weak balance sheets, and so on. The cash strains throughout the economy are eliminated, asset prices recover, and demand, output and employment all revive. So the monetary (or monetarist) view of banking policy is in sharp contrast to the credit (or creditist) view. Contrary to much newspaper coverage, the monetary view contains a clear account of how money affects spending and jobs. The revival in spending, as agents try to rid themselves of excess money, would occur even if bank lending were static or falling.”

http://standpointmag.co.uk/node/1577/full

Dehbach “You need to account for the real but ill-measured consequences of unemployment such as the effect on children, the crime rate and the such.”

-Couldn’t some of those ill effects be ameliorated by paying people a citizens’ dividend without asking them to do work for it? People might then be free to do voluntary work addressing community needs that they themselves had identified or to do work that didn’t pay well but wouldn’t otherwise be done and that they considered worthwhile.

Bill’s post does a great job of picking apart some of the myths about Japan. But he could have taken it one step further…

Real GDP growth PER CAPITA has been astonishingly similar in the US and Japan since 1980. The biggest differences are Japan’s burst of higher growth in the late 1980s and then the negative effects of its austerity in the late 1990s. See this graph:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=98

Japan’s stagnation myths mostly rely on two sources of confusion — real growth versus nominal growth (given Japan’s low rate of inflation) and GDP growth versus per capita GDP growth (given Japan’s low-to-negative population growth trend). Of course, the real GDP growth (not per capita) does affect valuations of financial markets and real estate, since those valuations rely on the size of future earnings streams. To the extent that other nations follow in Japan’s demographic footsteps, there will be some downside surprises in asset market returns in the medium to long term for many advanced nations…

Bill, you noted that “The contributions do not usually exactly add up to the GDP growth figure because of statistical discrepancies inherent in the National Accounts.” I actually created some very similar graphs for Japan and the US last August, likely from the same data sources, and noticed the same thing. I then switched from calculating it myself (your “Contribution = 100*(A(t) – A(t-1))/GDP(t-1)” formula) to using Japan’s pre-prepared contributions to annual real GDP growth data. The biggest difference between my calculations and their prepared numbers was with net exports… I think it might have something to do with how price deflators are derived — perhaps differently with foreign trade? But I didn’t spend much time investigating and could be wrong on this.

Interesting note on how Japan calculates unemployment:

5. Why are those who worked only for an hour during the last week of a month regarded as employed?

Like other major advanced countries, the definition of the “employed” used for Japan’s Labour Force Survey conforms to the international standard stipulated by the ILO to grasp the employment and unemployment status objectively.

The ILO defines the employed as follows:

The “employed” comprise all persons above a specific age who during a specified brief period, either one week or one day, were

(1) “paid employment”, i.e. persons who during the reference period performed some work for wage or salary, in cash or in kind (include persons with a job but not at work), or

(2) “self-employment”, i.e. persons who during the reference period performed some work for profit or family gain, in cash or in kind (include persons with an enterprise but not at work).

Note:

the Labour Force Survey also asks the employed about their working hours. According to the Labour Force Survey (2010 Yearly Average), persons who worked for an hour or more during the last week of a month are 61.29 million, of which, 410,000 worked for one to four hours.

Leaving the Euro Zone is not so easy.

There have been very few analysis on the legal aspects of “thinking the unthinkable”.

Charles Proctor and Gilles Thieffrey analyzed this in Thinking The Unthinkable – The Breakup Of The Economic And Monetary Union and Thieffrey summarized this in Not So Unthinkable – The Break-Up Of European Monetary Union

The authors talk of Negotiated Withdrawal, Unilateral Withdrawal and Alternate Scenarios.

Charles Proctor is the author of Mann On The Legal Aspects Of Money – the book expanding on previous versions by Fritz Alexander Mann.

the departing state would have to accept that its new currency may not be recognized in other member states

What does that even mean, and why should the departing state give a flying f**k?

I think that a country leaving the Euro would be easier then you think. Sure there will be consequences under various treaties, such as the right of Irish citzens to move about the Euro as they wish, and they may face fines or penalties in Euros (which they probably do not have) but as long the Irish feel that they have chance to live their lives (ie they have jobs, security, education for their kids, healthcare, a roof over their head) then those other issues can be worked around and may seem trival in comparison.

I find it interesting how the people that are totally against unproductive labour are the same one who think work for the dole is a good idea.

Thanks for the clarification on the data, Bill (and Warren). Curiously, a few “Austrians” tried to argue the same point (unemployment was way higher, hence fiscal policy fails) and all that sort of non-sense.

IMO, Japan should be a good case to study about the differences between creating more medium of exchange from the demand deposits created from private debt, from the demand deposits created from public debt, and from currency with no bond attached.

In relation to what bill talks about, I’d like to see the differences between the last two.

“Japan proves over and over again that a currency issuing government cannot become insolvent and that the public debt ratio can go to 200 per cent (well above the IMF 80 percent insolvency limit) and beyond without any problems at all.”

I’m still thinking they are vulnerable to interest rate increases and/or the rollover problem.

“The departing state – and entities carrying on business within it – would thus be exposed to new exchange risks.”

You could easily solve that in the Chinese fashion – particularly if you kick up the export system.

A domestic currency doesn’t need to be used by anybody else.

The main issue would be trade barriers erected agains the leaving nation – which would rightly be seen as blackmail.

Fed Up: I’m still thinking they are vulnerable to interest rate increases and/or the rollover problem.

That’s the crucial point. A debt/gdp ratio of 200% or 800% is irrelevant as long as the interest rate on it is 0.

But it exposes you to even small increases in the interest rate which would be inflationary.

But MMT claims the government can set interest rates on debt at whatever level they wish. I don’t think it’s possible without being exposed to other inflationary pressures, but it all boils down to whether it is possible or not.

Neil: A domestic currency doesn’t need to be used by anybody else.

Only if you don’t need to import, or if you are willing to export in a foreign currency, but that doesn’t make you monetarily sovereign, as previously discussed.

“You could easily solve that in the Chinese fashion – particularly if you kick up the export system. ”

Well, don’t want to enter this again and again, given some hostility from both sides. But thanks for engaging on these issues.

I really found this argument strange, Neil. Its far from “easy”. Exports of a nation depend on its competitiveness relative to other exporters from other nations as well for example and hence the propensities to import of nations abroad. It also depends on the demand abroad. A nation cannot set its export levels.

Ramanan: I really found this argument strange, Neil. Its far from “easy”.

I didn’t dare to go into that again, but I totally agree with you.

“Only if you don’t need to import, or if you are willing to export in a foreign currency, but that doesn’t make you monetarily sovereign, as previously discussed.”

So you are suggesting that China isn’t monetarily sovereign because it exports primarily in US dollars?

‘ Its far from “easy”‘

The chances are that trade would continue in Euros unaffected by anything else. The exchange risk would just sit with the seceding nation – which could be eased by the government swapping them for the domestic currency just as the Chinese do in an effort to boost exports. That step may be unnecessary.

The world of trade doesn’t end just because a few bankers and bureaucrats got a bloody nose. Businesses don’t suddenly change suppliers because the government tells them to.

Re: leaving the euro, the purely legal issues can be easily overcome. Other nations may complain but they aren’t going to start a war over it. But economically, it would be very painful in the short run. The path of least resistance is to accept bail-outs.

So you are suggesting that China isn’t monetarily sovereign because it exports primarily in US dollars?

No, it’s because China imports in dollars. Exports have nothing to do with being monetarily sovereign.

I lived in a remote Tokyo suburb for three years in the 90’s. The little streets were like country lanes, no pavements for pedestrians, cars driving at about 10mph.

They were empty during the working day. In this country of low unemployment, you would see uniformed young men and women with hard hats, standing for hours with flags, whistles at the ready, to direct the (non-existent) traffic when there was any work being done on the infrastructure. It wasn’t funny, it was weird.

A nation cannot set its export levels.

Nations can influence export levels and they also do so, economically and politically. On one hand, China manipulates its currency. On the other hand, the US has a lot power to influence exports politically and often brings pressure to bear on other countries to increase importing from the US in order to continue exporting to the US. The US enters into trade disputes to send a message that will curtail imports unless US exports are increased.

Part of the deal with oil producers is that they will exchange a good portion of USD received from oil profits for US military hardware. These things don’t happen just because of the free market.

In addition, reported trade figures are not completely representative of reality. Take the iPhone, for example. It’s a booked as a Chinese export even though China has only $6.50 in it. See_http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/6335

Tom,

But not “easy”.

US can ask others and pressure to some extent but can’t set it exports. Its not easy.

China manipulates its exchange rate but again doesn’t set it exports. For example, a deflationary scenario in the US – as during the crisis – reduces income in the US and hence imports as well. Its dependent both on China’s competitiveness and demand in the US. Some other nations also peg their exchange rates, certainly they do not set the export levels.

“reported trade figures are not completely representative of reality.”

Don’t see the relevance of this here.