The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Europe is still pursuing the wrong goal

Europe has another … yes, yet another … solution. But we have to wait until June for it so be fully revealed. Meanwhile Portugal is about to go under. There are simmering stories emerging that the banking system in Europe is teetering despite there being silence on the viability of the banking system in Europe from the Euro bosses. Despite the decisions (or rather non-decisions) of the European Council last week – the intent is the same – fiscal consolidation including retrenchment of safety net benefits supplemented with further labour market deregulation which will further reduce living standards, especially for the poor. Their position is a denial of basic macroeconomic understanding and doesn’t address the inherent design flaws in the monetary union. I predict things will get worse. The political leaders in Europe have the wrong goal in mind (stubbornly saving the euro) and do not even have an effective solution to defend that goal, flawed as it is. The problem is that Europe is still pursuing the wrong goal.

By way of introduction, I note that the European Central Bank (ECB) has developed some propaganda tools in the best traditions of their location. They are calling them Educational Games. I proved to be an exemplary manager – I immediately cut the interest rate to zero and got unemployment down to zero (what no frictions?) and then looked for some fiscal instruments to keep inflation in check and found that the “educational game” didn’t provide any fiscal policy capacity.

So how it is educational to deny the existence of the most important tool governments have to regulate aggregate demand – and hence employment and inflation? I would call it ideological brainwashing.

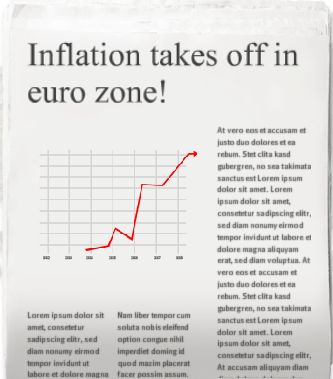

The following graphic is the headline report the “game” produced to describe the inflation record of my administration as central bank boss. By 2018 inflation was soaring. Hardly surprising if you prevent a government from using fiscal policy.

Readers might be interested to know I am developing a similar game based on MMT principles. That game will include both arms of macroeconomic policy in the interests of education. But like all these “educational models” the results you get are predictable – the model is pre-configured. But unlike the ECB game our model will have empirical content – that is the equations will be conditioned by what the real world looks like and behaves like rather than the numerical world that comes from the application of abstract (and erroneous) macroeconomics textbooks.

But the bias in the ECB game is broadly symptomatic of why Europe is in such a mess now and on the brink of further collapse.

Last year, the European Council’s Summit (March 25-26, 2010) outlined “a new strategy for jobs and growth”. That didn’t last long.

At this year’s Council meeting (March 22-25) they came up with these conclusions. The shift in emphasis is a reflection of how bad things have gone since last year in the Eurozone.

They plan to “lay the ground for smart, sustainable, socially inclusive and job-creating growth”. So what happened to last year’s “new strategy for jobs and growth”. It wil

In the conclusions of this year’s meeting you get an inkling of why their strategy is failing:

Within the new framework of the European semester, the European Council endorsed the priorities for fiscal consolidation and structural reform.1 It underscored the need to give priority to restoring sound budgets and fiscal sustainability, reducing unemployment throughlabour market reforms and making new efforts to enhance growth. All Member States will translate these priorities into concrete measures to be included in their Stability or Convergence Programmes and National Reform Programmes. On this basis, the Commission will present its proposals for country-specific opinions and recommendations in good time for their adoption before the June European Council.

You learn that the austerity approach – what we might call the denial of macroeconomic realities is very much in the minds of the political leaders in Europe. They think that by cutting public spending at a time when private spending is weak and likely to nosedive that there will be the growth in aggregate spending necessary to stimulate jobs growth.

But it gets worse than that – they think that the jobs problem is microeconomic in nature – that is, sourced in wage costs relative to productivity.

You also learn – and tellingly so – that they are not going to do anything until June anyway … European political leaders are the experts at saying everything and doing nothing – and when they do act it is because they are forced to by a crisis hammering at the front doors of their parliaments.

In the UK Guardian article (March 29, 2011) – Europe needs its own IMF – there is an argument outlined that the German construction of the crisis in the Eurozone – the “lack of budgetary rigour and low productivity of Mediterranean countries” is false.

The Spanish writer says that this falsity meant that :

… attention is diverted from the real causes of the crisis, namely the European Central Bank (ECB) following in the footsteps of the American Federal Reserve, maintaining low interest rates that generate property market bubbles, and the ease with which the private banks (Spanish, German, French and others) financed the property boom throughout the eurozone. The Spanish experience shows that these ideas don’t work.

The article, is in some senses, a defence of Spain, which has been vilified for having lazy, siesta-liking workers who like to spend too much. The author provides some interesting economic data to show that “Spain entered the monetary union having complied with the Maastricht requirements. Germany and France didn’t”; that “Spanish sovereign debt was, and continues to be, the lowest of the large European countries in terms of percentage of the GDP”; that “the productivity by those in work in Spain was actually higher than the eurozone average for the years 1981-1990 and 2001-10”; and that “the annual growth rate of Spanish exports averaged 6.1% between 1997 and 2010: rather more than Germany’s 5.3%”.

All interesting and good to counter some of the more pernicious dogma that comes from Germany and elsewhere – but largely irrelevant.

The reason that the bond markets are “attacking” Spain, as they have attacked Greece, Ireland, and more recently Portugal is because the Spanish government is exposed to insolvency as a result of ceding its currency issuing monopoly to the ECB.

The reason the Spanish “government has had to respond with the most severe package of measures in recent decades: tax increases” is not because its deficit was too high relative to the other aggregates in that nation (private domestic and external balances) but because the European political leaders have a totally distorted view of what macroeconomic management is about – exemplified by the ECB “educational game”.

It is clear that when a nation that has no currency sovereignty is hit with a major negative demand shock

I am not absolving the Spanish government or any of the EMU member state governments of being delinquent in their regulatory duties as the property developers and financial engineers (banks mainly) set about creating the house of cards that collapsed. Clearly that is the coincident cause of the crisis.

But the subsequent inability to respond to the crisis in a satisfactory manner – and instead be forced to scorch the domestic economic landscape – is the consequence of the fatal design flaws that were evident (and deliberately so) in the creation of the monetary union.

I have written extensively about these flaws previously. Please read my blog – Doomed from the start – for an example. You might also like to explore the other blogs posted under the Eurozone category of my blog.

The basis point is that when a number of states (countries) cede their currency issuing monopoly to a federal level (in this case, the ECB) (which also means they, in effect, agree to operate under a fixed exchange rate regime) and cede their monetary policy to a federal-level central bank, the ways of adjusting to a negative demand shock (private spending collapse) become severely limited.

For a normal sovereign nation operating as a federation, such as the US and Australia, the states (California, New South Wales etc) are secure (relatively so) in the face of such a shock because it is understood that the national government is acting in the interests of all states and will engage in fiscal transfers where appropriate to attend to “state” problems arising from the recession.

Further, the automatic stabilisers that are built into fiscal policy – that is, the taxation revenue and the welfare and other payments that vary with economic activity – provide the safety floor below which aggregate demand will not fall as private spending declines. Public net spending automatically increases, even if the fiscal policy stance of the government of the day is restrictive. The expansion of public spending provides some relief.

The automatic stabilisers in different nations will vary in the extent to which they provide that relief – and that responsiveness is governed by the design of the tax and transfer systems.

Further, the floor that the automatic stabilisers put in place might not be very satisfactory from the perspective of avoiding large rises in unemployment – and then there is a need for discretionary fiscal intervention. But they do prevent things from spiralling out of control.

Not so in Europe. They have designed a system that deliberately imposes pro-cyclical fiscal policy changes on their economies in the form of austerity packages. By design, the push for austerity is a deliberate attempt to negate the operation of the automatic safeguards.

The political leaders – reaffirmed in the European Council meeting’s conclusions last week – have deliberately imposed a system of fiscal consolidation onto the member states which means that fiscal policy is now reinforcing the negative demand shock coming from the private sector rather than countering it – which is how a responsible government would act.

It is ironical that all the mainstream macroeconomic textbooks criticise the use of fiscal policy exactly because they accuse it of being pro-cyclical. In this context, they claim that political issues, implementation lags etc lead to the net spending injection being “too late” and reinforcing a recovering private sector demand. In other words, it is alleged that fiscal policy starts working when it is too late (the emergency is over) and only reinforces the inflation risk arising from the recovery.

While empirical evidence for that allegation is mixed and mostly non-conclusive, I find it amazing that the mainstream economists advising the Euro bosses can keep a straight face when pushing the politicians to implement exactly what they claim is mis-use of fiscal policy.

It seems that when pro-cyclical fiscal policy is causing job losses and poverty it is fine for the mainstream, but when it is driving growth it is not. That should tell you a lot I think.

But the lack of a fiscal reallocation mechanism in the EMU (save the ad hoc interventions by the ECB at present – which is holding the system together) is the real problem and is pushing the Eurozone ever closer to collapse – which might take the form of major debt defaults from some of the member states.

The Guardian writer (the Spaniard) agrees that there are fatal design flaws in the EMU:

The response to the crisis by the most powerful countries in the eurozone has been totally inadequate, above all due to Germany’s reluctance to help out the countries most affected by the crisis, keeping its citizens convinced that such actions would be rewarding irresponsible southerners at the cost of the “virtuous” north.

Successive German governments have not been able to explain to their citizens that the creation of the euro constitutes an excellent deal for the country, a deal by means of which their exports have grown from 24% of GDP in 1995 to 46% in 2010 while those of France, Italy and Spain have stayed level at 26%. Therefore, when sheer common sense dictates the need to strengthen the stability fund, it has had to be adorned with lessons and “penalties”.

The creation of the monetary union did not address the fact that imbalances between such varied economies would need some entity similar to the International Monetary Fund. Created in 1944 at Bretton Woods, the IMF combined the intellects of Keynes and White with the generosity of the US, and provided a mechanism that granted loans at bearable interest rates to help countries in difficulties without introducing Germanic penalty concepts.

So, in effect, he is advocating a “fiscal” capacity at the federal level.

But that doesn’t overcome the problem that the fixed exchange rate system imposes. It just would mean that the member states would have some independence from bond markets in extreme situations – which is no gain at all. And the IMF is not the exemplar of “easy” money. It would be likely that the “loans” would come with a major sting (as is evident now) which doesn’t really allow the member states to enjoy fiscal autonomy.

Further, the Bretton Woods system collapsed because it was unworkable. The nations with external deficits were always facing domestic recession (because they had to run tight domestic policies to ensure they didn’t destabilise their parity and run out of foreign reserves). This design problem became politically unviable.

So the introduction of the rescue fund will not overcome the design flaws in the EMU. Further ECB “fiscal” operations – which are really dislocating, temporarily, the member states from the bond markets – will help – but making these a permanent feature of the monetary union is unlikely because it would demonstrate that the system as designed is unworkable.

The Eurozone bosses resist any notion that they might have got it wrong! Their stubbornness is impoverishing millions.

I have more sympathy with the view expressed in this Bloomberg article (March 30, 2011) – Losing Euro in Defaults Brings No Threat to EU.

The writer notes that such a proposition:

… will be objected that the euro has to be preserved to keep the European Union together. That will certainly be the standard line from the Brussels- based elite during the next few years.

The Euro bosses have a vested interest in preserving their position at the top and the perks that accompany that position.

The Bloomberg article makes the essential point that is forgotten when the Euro bosses claim that “(w)e must save the euro to save the European Union”:

The European Union and the euro are not the same thing … Breaking up the euro will not break up the EU. It will change its character, but it needn’t be the end of the EU — just a particular version of it.

Yes, a particularly dysfunction version of the political union at that. One that imposes grief on its most disadvantaged citizens and prevents their elected representatives from being able to use the policy tools

that are available to sovereign governments to help alleviate economic stress.

If I was to design a system that was doomed to fail and in the process imposed massive damage on the citizenry my design would stray too far from the system the Brussels-elite came up with.

The Bloomberg article conlcudes:

By any reasonable measure, the single currency has been a failure. It hasn’t made the economies of Europe converge: If anything, they have moved further apart over the past decade. It hasn’t promoted growth, except of the most unsustainable and unbalanced kind: crazy credit booms in Spain and Ireland, reckless public spending in Greece and massive, pointless trade surpluses in Germany.

Nor has it shielded its members from financial instability: In fact, the euro has created instability, visiting a wholly self-made crisis on the European continent. It is a cause of instability, not a cure for it.

Looking forward, there are years of terrible austerity for the high-deficit countries, accompanied by big cuts in living standards and rates of unemployment that will make it virtually impossible for an entire generation of Greeks, Irish or Spanish to build careers for themselves.

In Germany, the Netherlands and France, there will be simmering resentments over the bailouts. Years of “Bild” front pages shrieking about lazy Greeks living well on German taxes will take an inevitable toll on what was until now the most pro- European of countries. Does that strengthen the EU? It doesn’t sound like it.

I agree with this assessment. The question is how long it will take before all the voters realise it – in the ways that they might seek to understrand things – and then social and political instability of the sort we are seeing in the Middle East at present become the norm rather than the exception.

Hanging on to a failed system – from my outsider viewpoint – exemplifies the disconnect between the political elites and the people in Europe. That sort of disconnect, in the absence of military enforcement, cannot last for long.

While the Bloomberg article says that the “most rational option would be competing currencies … re-creating the deutsche mark, the franc, the lira and so on” (which I agree – including the PUNT) – but then advocates keeping the Euro as “a financial currency” which might comeback as the core currency in some nations.

I do not advocate that and in another blog some day I will outline why (time has overtaken me today!).

More evidence from the UK

In Britain’s case, their response is just plain lunacy.

In the UK Guardian (March 29, 2011) – Real household disposable income falls for the first time in 30 years – we read that:

Britons’ take-home pay fell for the first time in three decades … the total income of Britain’s working and unemployed populations after taxes and adjusted for inflation – dropped by 0.8% in 2010, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The figures also showed that the decline is likely to accelerate to about 2.0% this year and flatten in 2012 as the biggest public spending cuts since the second world war begin in earnest.

The Guardian reminds us of number 1 hit from The Specials – Ghost Town – which rose to the top of the charts “the last time Britain’s real household disposable income fell”:

Government leaving youth on the shelf

This place, is coming like a ghost town

No job to be found in this country

Can’t go on no more

The people getting angry

More of that to come.

On the topic of reminiscent songs … Portugal is about to go under – and they have very bitter memories of the IMF interventions in 1977 and again in 1983. The 1982 song – FMI – all 20 odd minutes of it – by Portugal’s José Mário Branco – was a scathing attack on the IMF and its intervention which blighted the early hopes for a democracy that had just escaped 48 years of oppressive military rule. The IMF reprised its destructive intervention in Portugal in 1983. You can listen to it via YouTube – FMI Part 1 – FMI Part 2 (but is in Portuguese. The English lyrics are too long to post here but are interesting.

Conclusion

I am still in transit and have little time again today to write. So …

That is enough for today!

There’s no need to bring back the DM because the Euro is effectively a German currency anyway.

Glad to hear about the game! As for the United States, I suspect our one party of austerian regressives will try to force the states into “bankruptcy” and prevent the federal government from intervening.

I think of the Euro as a one of the first steps on a very long and painful road towards a Federal State of Europe maybe in 100 years or even more.

I’m not saying the current situation is good, they probably should have started the convergence with something else than an integrated monetary system (well it started with coal if I remember my history lessons, but who cares!).

Now they’re talking about fiscal consolidation (which I understand as making fiscal rules converge among all the EMU members, please correct me if it’s not what it means). Once all the major fiscal rules are harmonised in all the EMU members, the next step would be a European Treasury, and I imagine, would not be too difficult to achieve technically at that point. Politically that’s going to be tough though, but I’m sure it’s peanuts compared to having the French accept other languages than French as official European languages!

I’ve read somewhere that some European leaders already talking about building an entity that would sell bonds in Euros. So financial institutions would buy bonds from Europe and not directly from Ireland or Greece anymore, a sort of buffer to prevent “attacks” from the bond markets. Well, that’s following the great European tradition of doing things in the wrong order, but doesn’t it take the right general direction over the years? A sort of federal political model like in the US.

On a more emotional level, the Euro is one of the too few things that, on an everyday’s life basis, make European feel like European citizens (that and the Schengen area), take that away and we’re back to nothing.

I suggest the unemployed Greeks, Irish and Spanish should all move to Germany and claim unemployment benefits there. Maybe then the Germans would start to realize what they have done to Europe.

Another depressing survey for Britain:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/jobs/8416625/Fewer-workers-quit-their-jobs-even-as-pay-falls-in-face-of-rising-inflation.html

Otherwise, off topic, but I just received an email from HR saying that “Rt Hon George Osborne MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer” is going to visit our office. They’ve asked us to clean our desks, probably to avoid schoking the dear minister with the clutter of a desk used to do some actual work!

Hi Bill.

I am waiting for illustrative educational game that includes the misery austerity measures are causing. People out of work and we cannot afford to hire them. We cannot afford to create wealth.

“On a more emotional level, the Euro is one of the too few things that, on an everyday’s life basis, make European feel like European citizens (that and the Schengen area), take that away and we’re back to nothing.”

Until the Germans realise that the Spanish deficit is the reason they have a trade surplus and that they have to ‘fund’ transfer payments to rebalance things then you have nothing anyway. It is just an illusion.

We have enough trouble in the UK with transfer payments. The south east is constantly complaining that it is ‘funding’ the rest of the country.

The European community embarked on the Euro “adventure” with a number of objectives, including a most noble one. It was reasonably assumed that a common currency would further strengthen the *political* ties between European nations. And, irrespective of all else, peace in Europe *is* being achieved for the past sixty-plus years, which is remarkable when contrasted with centuries of continuous bloodshed and destruction.

A common currency, though, should not have been decided by central bankers and leaders of state, alone. The central banks’ focus on inflation; the leaders seek fiscal-cum-political discipline. A philosopher, at the time of Euro’s introduction, characterised the move as “barbaric”, in the sense that political unification was being sought through a currency unification.

The rest of the Euro’s story is known and understood by the MMT crowd. What’s important to add here is that getting out of the Euro would signify a major step backwards in the process of the European Union itself, of unifying Europe. But, it’d be a welcome backward step; let it come. We might witness a revision of the whole bungled concept of fiscal unification, which is part of the economic unification, in turn part of the political unification.

Who knows, we might even witness the emergence of a more democratic EU, as well, since, lest we forget, the EU’s decision-making process largely ignores those bothersome European electorates.

Hello Bill

What’s your opinion on the leaders of the Euro changing the rules for ECB and allowing it to participate in government bond auctions as buyer of last resort? It would certainly need ECB to sell bonds of the same amount in order to preserve it’s interest rate policy but it would give the South countries room to increase their budgets in order to combat unemployment and counter private sector’s savings. It might even be a positive move for Germany since it would increase it’s industrial capacity utilization.

Yep the game is hilarious. I really liked these freak characters commenting on my heavy hand monetary policy. The old lady – who is most probable retired – telling me “there are not a lot of unemployed people” while the unemployment rate was 7.xx% And this tired-looking young chick who relentlessly informed me about her “sleepless nights because of inflation fear” once the inflation rate was above 2.xx% Once the inflation rate was above 5.xx% I waited for some freak to show up and remind me of Weimar.

Yes Europe is a mess. And Germany is a particular mess. The nuclear debate is symptomatic how clueless our politicians are. Yesterday the power plants were 100% safe and their duration should be prolonged. Then Fukushima came along. Tomorrow the power plants must be inspected whether they are truly safe and for the time being are shut down. And BILD advises it’s readers how to operate Geiger counter which are then sold out. The same modus operandi applies to the €-crisis. What was true yesterday isn’t true tomorrow and the public is misled. But I’m still waiting for a credible plan how to dissolve the EuroZone. Want to lend us a helping hand Bill?

@Vassilis,

my point exactly, although I think that getting out of the Euro would not be welcome. As you point out it would be a backward step for unifying goal of the European Union. Since the Euro was a step towards this goal, why go back? Admittedly we’ve not done things in the ideal order, but let’s push for more unification rather than going back.

I don’t think the French saying “reculer pour mieux sauter” (litterally: to draw back in order to make a better jump) really applies to politics, with political momentum being so hard to shift. Imagine the mixed message to the electorates “Kill the Euro for a better Europe”, many people would think politicians have gone mad (if they don’t already!).

Going back would shatter the very idea of the European utopia, and I also think this would break the political momentum that has built up over those years. And that would be very difficult to build this momentum back.

The price is very high but the reward will be worth it if we can make violence in Europe a thing of the past. It’s up to the European people to force the elites in the right direction, and I’m sure most of the European citizens reading this blog do what they can to, if not make other people adhere to MMT, at least make them question the propaganda being forced down their throats. That’s the least we can do.

@Neil Wilson

“Until the Germans realise that the Spanish deficit is the reason they have a trade surplus and that they have to ‘fund’ transfer payments to rebalance things then you have nothing anyway. It is just an illusion.

We have enough trouble in the UK with transfer payments. The south east is constantly complaining that it is ‘funding’ the rest of the country.”

Spot on.

Of course in the early days of the EU, countries like Spain profited from such “development” transfer payments. You only have to look at the improvement of roads in the more remote parts of Spain to see this. Other parts of their infrastructure were similarly brought up to “First World” standards. But these also opened up new markets for the Germans … The latter have to realise that they can’t have their cake and eat it. But I guess domestic politics and economic orthodoxy kind of get in the way.

“The price is very high but the reward will be worth it if we can make violence in Europe a thing of the past.”

Violence in Europe is pretty much a thing of the past. Continuing to use that excuse to force people who don’t want to integrate to integrate some more is not acceptable.

The EU doesn’t prevent violence. Common sense prevents violence.

There is a school of thought, the mammothian school, that recognizes that EZ countries have lost their monetary sovereignty, but not their ability to tax. Countries which experience problems now are those who have had the highest inflation rates since the adoption of the Euro which resulted in a loss of competitiveness, which they could have avoided by raising taxes to decrease aggregate demand as MMT suggests. It was not a failure of the Euro, but of the fiscal policies of these countries.

Hail the Euro!

Having a common currency is like having a common language. The Euro was designed as a “trade dollar” or financial currency from the start.

The idea that adjustments between nations in terms of exchange rates would no longer be necessary is complete idiocy. Europe can only move forward when the Euro is abandoned.

@Neil,

I am not advocating forced integrattion. For example, the UK’s never been so hot on the European Union and probably never will. Nobody forced the Euro on the UK, and the UK refused it. That’s fine. The members of the EMU joined because people voted for it, nothing has ever been forced. I agree that probably not all the consequences of doing so were understood by all who voted to join at the time, but I doubt the idea of integration was one of them. Actually, if I remember well, it was the only reason advanced by the “yes” side of the debate at the time (at least in France).

Any nation that wants to get ou can do so if the people want it. Nobody’s talking about forcing them to stay. That would indeed be unacceptable.

What I’m saying is that countries that are members of the EMU cannot stay half way through integration. I’m obviously on the European utopists side, and I advocate for more integration. I’ll live my own utopia in my head if nobody wants to play with me… :sobs:…

As for common sense, I haven’t seen it preventing Afghanistan, Irak or now Lybia, so I won’t rely on it to prevent violence.

“The members of the EMU joined because people voted for it”

One or two had to vote several times though until they got the right answer…

Anyone who thinks a common currency can wash away cultural differences need only look at the United States to learn otherwise. Here, we have been working on the “reunification” of the North and the South for a century and a half, never quite getting it that there never was a union to reunify in the first place.

P.S. A good translation of F.M.I. is provided by Google here:

http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=pt&u=http://www.gugalyrics.com/JOS%25C3%25A9-M%25C3%25A1RIO–BRANCO-F.M.I.-LYRICS/35008/&ei=HoqUTcD6NsOftweWraGEDA&sa=X&oi=translate&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCIQ7gEwAQ&prev=/search%3Fq%3Dfmi%2Blyrics%26hl%3Den%26rls%3Dcom.microsoft:en-us:IE-SearchBox%26prmd%3Divns

MamMoth,

In a country that’s not operating at full-employment the last thing I would want to do is reduce aggregate demand.

With respect to inflation you are definetly looking at it too cheap. The dynamics of inflation are very complicated and well beyond myself or you to explain in ten-thousand words let alone two-hundred or so.

Is the inflation you speak of purely a demand side phenomenon or could it be the result of supply side effects as well ?

Far too complicated for me to decipher but good luck if you can find an answer.

“The members of the EMU joined because people voted for it, nothing has ever been forced.”

What are you talking about? If there would have been a ballot whether Germans want to trade in their much loved Deutsche Mark for the Euro there would be no Eurozone now. The people would have rejected the adoption of the €

People didn’t vote for those parties that rejected the Euro either.

@Stephan,

I’m talking about the 1993 Maastricht treaty that was adopted by referendum in France. I was too young to vote at the time but I clearly remember my parents not giving a penny about it 🙂 Wasn’t there a referendum in Germany too?

I remember plenty of debates including a very large part about a European common currency at the time of adoption.

@Neil,

I totally agree that some national governments have handled the adoption of the treaty in an unfair way (Denmark and Ireland I think). I think the French government would have done the same had the French said ‘no’. I don’t agree with these methods, whatever the result was and whatever side I’m on. I agree that ‘no’ means ‘no’, not ‘ask again’. So yes, in light of those facts, I concede that integration might have been forced to some extent and in certain cases, but I think we are talking about 2 or 3 countries out of 12 at the time. People could also have stuck to their opinions though, but that’s the militant in me talking… 🙂

Politics set aside, wouldn’t a full-fledged integration (with a European Treasury) allow MMT to be applied accross the board at the EMU level? I mean what would be the difference between that and any other nation made up of several federal states?

I’ve just been reading Stephanie Kelton’s working paper

“can taxes and bonds finance government spending”

Its probably familiar to everyone but I can’t believe this all this stuff has been ‘out there’ so long.

This was published in 1998. Where have the mainstream been keeping their heads for the last 15 years?

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=115128

“I mean what would be the difference between that and any other nation made up of several federal states?”

In all large federal systems you have the problem with the legitimacy of transfer payments. Introduce a float and that issue goes away.

I would argue that a co-operating group of smaller autonomous units would be a better approach – particularly now we have electronic payment systems where obtaining the currency required to make a transaction is near painless.

The centralised EU is an out of date idea from a bygone era. It needs to go back to its original format of a Common Market.

Tristan, did Ireland and Denmark reject the Maastricht Treaty? I don’t think so.

I don’t know which countries held referendums at the time, but the Treaty had to be ratified by parliaments across Europe.

Those who opposed it could have voted for any party that was against the treaty or the Euro. They didn’t.

The problem was not the Euro but of a wrong fiscal policy that didn’t tackle inflation as MMT suggests it should do.

“In all large federal systems you have the problem with the legitimacy of transfer payments.”

Isn’t that pulling us back into the political debate? As in “Would the German accept ‘paying’ for social security and/or pension benefits of a less economically dynamic region?” Doesn’t it relate to the notion of solidarity and caring for the less strong/able/lucky? (which I see as a political not economical issue)

In a full-fledged MMT system (with JG and all), would there even be such a thing as less economically dynamic region?

@MamMoth,

Denmark definitely did reject it, at first, and then when the Danish government heard ‘ask again?’ instead of ‘no’, they had another go at it. Ireland I’m less sure, hence me qualifying my remarks with uncertainty by saying “I think” :).

Tristan could be about Denmark, they aren’t part of the Euro Zone, so it makes sense…

Don’t think Ireland did.

I dont think the euro will collapse. By now French, Italians, Germans etc know they are all Europeans, i dont think they want to go back. They will do all they can to save the euro and they will support an european fiscal union. I think it’s just a matter of time, if the elites speed up this fiscal unification process they will succeed in avoiding state defaults otherwise there will be some defaults but the euro will survive them.

I agree with Tristan, during this process we will have to force the elites in the right direction ’cause they will try (as they’re already doing) to capitalize on all these events squeezing european workers. The problem here in Italy (and in all Europe i think) is that the debate about what should be done is totally in the hands of the neo-liberal elites, so it will be very difficult to have some kind of influence on it.

If you are worried about intra-Europe war (seems like an outdated concern to me…), wouldn’t it make more sense to persue military integration? Hard to have a war between Germany and France if they have the same military.

@Tristan

Only 3 countries had a referendum on the Maastricht treaty: Denmark, Ireland and France. The rest adopted the policy: better not to ask The People. The Euro is a creature of bureaucrats and evil economists without the consent of the people. That said I’ve nothing against the € if institutions would be in place for the United States of Europe. Unfortunately we’ve a long way to go even before envisioning the United States of Europe. Right now I’m only reading bogus news about Greeks dancing Sirtaki all day long and Spaniards having an 4 hour lunch break to indulge in Tapas. OK to be fair the news about Ireland is good. They are really trying hard to fit the stereotype required by German BILD readers. Wondering when BILD will come up with a black big bold headline: National Tragedy! Ireland committed suicide. BILD asks it’s readers for donations.

@MamMoTh

“People didn’t vote for those parties that rejected the Euro either.” You seem to be an expert on a wide variety of subjects. Can you please inform me what German party rejected the Euro so that German voters had a chance to say NO to the adoption of the € provided there would have been a referendum on the subject in the first place. Not that it does matter to me as I’m an alien in Germany and can’t vote anyway. BTW: Denmark is de facto member of the Eurozone since their stupid government pegged their currency to the Euro.

The clever government of Denmark pegged their currency to the Euro, but didn’t adopt it. All gain no pain.

If there was no anti-euro party in Germany it doesn’t matter.

It only proves people didn’t care about it enough to start an anti-euro party.

@MamMoTh

You are really an expert on everything and nothing ;~) My dear friend check out this link and start wondering whether “all gain no pain” is a wise strategy by your “clever” government of Denmark:

delete_me_http://rwer.wordpress.com/2011/03/30/thought-for-the-day-a-rotten-trap-in-denmark/

@Neil @4:20

“I would argue that a co-operating group of smaller autonomous units would be a better approach – particularly now we have electronic payment systems where obtaining the currency required to make a transaction is near painless.”

Good point. My recollection is that the Euro adoption argument had its political, ‘common interests-keep-the-peace’ element, but that much of the economic rationale was predicated on cross-border transaction cost frictions. Somebody could probably program an I-phone app by tomorrow morning that would solve that entire problem.

What is your definition of “float” in the federal context as you are using it here?

@Stephan, sure. What kind of protocol is that? The Danish can end the peg whenever they want.

@Lee: cross border transaction cost frictions because of exchange rates

“Somebody could probably program an I-phone app by tomorrow morning that would solve that entire problem.”

Probably most of the friction is the volatility of exchange rates rather than the cost of conversion.

A peg is the most extreme form of intervention to reduce volatility.

Mammoth, and Max,

Yes essentially, and most routinely in the tourist and merchandise movement contexts.

Production contracts and cross-border supply chains are certainly trickier, but I bet some incentivized ISDA techiophile could put together an FX swaps app by tommorrow…afternoon. 🙂

Bill,

And Music matters.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dd3btVhwr48&feature=related

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telegraph_Road_%28song%29

Detroit in the Reagan Era. Note the album title.

Just an interesting link re Portugal and how the ECB screws with them

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-07-21/gold-makes-dead-portuguese-dictator-top-investor-without-gains-to-prove-it.html

@MamMoTh

In terms of trade between Eurozone members the EZ is a closed system. One county’s trade surplus is another country’s deficit. The only reason Germany has such high exports is because other Eurozone countries decided to borrow and buy it’s products. Yes, Germany is more competitive and has been keeping it’s labour costs low (especially in comparison to other Eurozone countries) since the adoption of the Euro. There are two points though:

1) Even if the PIIGS tried to remain competitive there’s no reason to not assume that Germany would just try harder to maintain it’s advantage.

2) If PIIGS did manage to strengthen their foreign sector that would ultimately mean that countries such as Germany and Holland would see their trade surpluses diminish. In that case the question you should ask is if Germany is indeed ready to follow any growth strategy other than an export oriented economy, especially given it’s inflation fearing history.

Portuguese GDP was of 173 billion (10^9) € in 2010. Portuguese current account in the same year was roughly -10% of GDP at -17 billion, distributed as Goods -18, Services +7, Rents -8, Remmitances +2 . with first moments of 0.7%, 12%, -9%, 2%, all indicating an exchange situation driving to greater equilibrium except for goods.

Driving the current account to 0 means to consume less or to produce more a total of 17 billion € per year worth of goods or services in any combination. Services are growing pretty well while rents are diminishing nicely and remittances had positive behavior. Critical items contributing to the goods account value include oil and coal, food, pharmaceuticals, hardware equipment. Let one assume that country could come to produce 2.5 billion worth of more the last three critical imported goods from instant 0 taken to be this year. That would diminish Eurozone exports for Portugal, and would appease northern Europeans legitimate protest of producing real wealth for Portugal at no payment in a process that obviously does not lead to economic convergence. No exports, no real goods.

Say that -7.5 billion were subtracted from the -17billion to become a more manageable -9.5 billion at a rate of -2.5 billion/year. Assuming diminishing rents, say that at the end of three years, one would be at -17 billion to send abroad. That would take to 8 billion the increment needed in services or remittances. If only through services that would mean to grow the sector at 30% / year to 15 billion.

Such scenario, would cost -16 billion of increased debt and interest at the end of 3 years.

The required growth rates of GDP to break even current account in 3 years and stopping growing indebtedness would be a miracle cube root of 0.1 (3.2% and above) to make for the lacking 10%. That would require increasing the productivity of the global workpeople (employed and unemployed) by the same amount.

Some of the arithmetic of the problem. Portuguese are notoriously good as poets, travelers, sailors, merchants, but also known by having some difficulties with maths… Maybe this time they become interested in the power of knowing to do maths…

The math of the problem for Portugal is as above and the relevant restrictions are independent of the currency supposed, pegged or sovereign. Suppose Portuguese sell all their euros to Brazilians in exchange for reais effectively adhering to the real currency? Big business for Brazil at the risk of -17 billion euros per year? Big business for Portugal at the cost of exporting 17 billion euros to Brazil? Things would be pretty much like they are now for all the involved but with greater resilience. A no-loosers deal that could even allow Portugal to recover its currency. That are singular peoples in Earth and one of them is the Portuguese. Clearly, it is better for all that the Portuguese have its own sovereign currency…

Actually, different nations very naturally require different currencies. The extent of political union and of currency tend to coincide. For Europeans the political union required to support an working common currency is unthinkable. United States, Australia, Brazil, Germany, even if federal states are nations. One nation, one state, one currency. An European Union with a common currency would tend to become one nation. That would be an incredible loss for the wealth of Europe, the loss of nations in a melting of decaying diversity and resilience. Ergo, if Europe is to preserve as a continent the potential and wealth of diversity, the euro is an experiment without future.

Irish anti-IMF song by Soundmigration

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qNEoOvMd8-Q

Lee,

I’m suggesting that currency unions under modern electronics should be going the other way. I’m sure I’ve read somewhere before what makes an optimal currency area. From where I’m stood it looks like ‘population feels sufficient kinship with poorer areas to continue to fund transfer payments’.

It looks to me like that is shrinking in a modern world rather than growing.

I’m a bit late to the discussion, but let me add a point that has not been mentioned. While I think it is important to explain how Euro member states could benefit from leaving the Euro zone, I believe that MMT advocates should *not* advocate the dissolution of the Euro zone.

What would happen if e.g. Ireland were to leave the Euro. Most likely this would help Ireland in the mid-term because of floating exchange rates. However, it would go along with an Ireland debt default, and given how the odds are stacked against MMT, this would be seen as additional evidence that large debts / debt-to-GDP / whatever are unsustainable and lead to default. We all know that that is false, but unfortunately, this is how it would be perceived by the vast majority of the population, including the people currently in charge. Furthermore, it would most likely lead to Irish governments implement heavily contractionary fiscal policy in the future, in pursuit of budget surplus because of their fear of repeating the debt default. Again, *we* know that that fear would be unfounded, but that doesn’t change public perception.

That is not to say that leaving the Euro couldn’t be used as a strategic threat. For example, if a successful outreach to Irish workers (again, just an example, the same would be true for any other Euro member state) were successful in establishing an Irish government that understands MMT. Then this government could make the establishment of a JG its goal, and basically blackmail the Euro bosses by saying, look, we are going to implement this JG. Either you establish mechanisms by which we can pay the JG wage without raising taxes or selling bonds within the Euro zone, or we’re going to leave the Euro zone and just do it ourselves.

Given that the ECB will want to maintain its grip on power, it would be interesting to see how they react. If they allow the JG to be established, then this gives MMT a chance to be demonstrated in practice within the Euro. If they let it come to a fracturing of the Euro zone, then there is still an MMT-aware government in Ireland that will default on Euro-denominated debt, but at least then the fracturing of the Euro zone happens with MMT already widely-enough spread – as opposed to the first scenario I’ve outlined where the Euro zone fractures *without* having MMT be widely spread.

The point is that you might succeed convincing Ireland to leave the Euro before the message of MMT has reached a critical mass – and that would be a mistake, if your goal is to advocate MMT.

Then this government could make the establishment of a JG its goal, and basically blackmail the Euro bosses by saying, look, we are going to implement this JG. Either you establish mechanisms by which we can pay the JG wage without raising taxes or selling bonds within the Euro zone, or we’re going to leave the Euro zone and just do it ourselves.

The word blackmail seems completely out of context, but that is not the question. If a country has critical items in a (deep) negative current account, care must be exercised to keep money to buy these critical items, like dollars for oil.

Kinda looks like Ireland is heading for default no matter what.

Technically it would be possible to introduce new medium-of-exchange alongside euro. All state have to do is to accept payments of tax liabilities and other obligations to the state in this new currency, that would create demand for it. Then it could spend it to the existence by various state expenditures. Why not give it to every state employee as a bonus, on top of the euro-nominated wages.

Greatest obstacle to anything like this is that euro is not even been seen as the root of the problems.

Ireland could just start accepting its debt as payment for taxes at par. That would put a floor under it. Similarly with Portugal.

PG “An European Union with a common currency would tend to become one nation. That would be an incredible loss for the wealth of Europe, the loss of nations in a melting of decaying diversity and resilience. Ergo, if Europe is to preserve as a continent the potential and wealth of diversity, the euro is an experiment without future.”

-I totally agree. I get upset when people say that being in favor of European integration is being pro-Europe. To me what is special about Europe is its diversity. What puzzles me somewhat though is India. India seems to have a wide diversity of cultures and languages and yet has political and currency union. How do they manage it? I don’t know India but they seem to have as much diversity as Europe and yet function as one country.

Neil: I’m suggesting that currency unions under modern electronics should be going the other way.

I don’t think currency unions have anything to do with electronics.

From where I’m stood it looks like ‘population feels sufficient kinship with poorer areas to continue to fund transfer payments’.

It looks to me like that is shrinking in a modern world rather than growing.

Good point. Look at what happens even within countries, like the UK south-east as you mentioned, but even worse are the north of Italy and Catalonia and the Basque country in Spain…

@ Tristan Lanfrey

“In a full-fledged MMT system (with JG and all), would there even be such a thing as less economically dynamic region?”

I would venture a speculative response and answer Yes. In my opinion, differences in environmental factors, sizes of population, geographical attributes, natural resources, cultural and educational levels, etc, would very much delay, at the very least, an economic integration.

@MamMoTh

“The problem was not the Euro but of a wrong fiscal policy that didn’t tackle inflation as MMT suggests it should do.”

MMT is a descriptive perspective of Macroeconomics that can be used any way you want. You could, for example, accept as true all the premises of MMT and then just say – The hell with the unemployed! I suspect a few academics are on this trial but I have no proof…

But bear in mind that, by definition :-), the fiscally activist tools at the disposal of a currency-sovereign gov’t are not at its disposal when it’s …not a currency-sovereign gov’t! In others words, when it governs a country with a foreign currency, i.e. the Euro.

Finally, I do not know of what Inflation you are talking about. Europe was not in any kind of danger from inflation in recent years.

“The clever government of Denmark pegged their currency to the Euro, but didn’t adopt it. All gain no pain.”

All pain, no gain – more likely. Pegging it to the Euro is like withdrawing it off the exchange markets. Not the definition of a true fiat currency, at least not per MMT. Didn’t Argentina tried the same kind of “fiscal discipline” by pegging the peso to the US$?

I do not know of what Inflation you are talking about. Europe was not in any kind of danger from inflation in recent years.

The danger of relative inflation between countries, which is what matters with a pegged currency.

From 1997-2008:

Greece: 48%

Ireland: 44%

Spain: 42%

Portugal: 38%

Germany: 20%

EZ countries are still fiscally sovereign, especially when it comes to decreasing spending and raising taxes.

There is no problem with a pegged currency as long as you can maintain the peg, as China and Hong Kong shows.

Argentina did quite well with the peg until Brazil devalued its currency in 1998 and the dollar revalued at the same time.

Unfortunately they didn’t break the peg at the time which was a huge mistake.

The Danish are also politically sovereign, so they can stop the peg to the Euro if they want to.

Maybe they should do it now. I should look at their inflation rate…

Nicolai – Ireland leaving the euro and defaulting would not be a counter-example to MMT – quite the opposite!

MMT says that for a sovereign to incur significant debt in a currency in which it is not sovereign is asking for trouble.

Ireland did just that, and we’re seeing the consequences.

@MamMoTh :

“The danger of relative inflation between countries, which is what matters with a pegged currency.

From 1997-2008:

Greece: 48%

Ireland: 44%

Spain: 42%

Portugal: 38%

Germany: 20%”

These are the cumulative sums of CPI increases over the period examined, which is twelve years. For example, for Greece, if 1997=100, then 2008=148. To get from 100 to 148, it takes eleven jumps of abt 3.65% yearly “inflation”, in cumulative, of course, terms. That doesn’t look too bad – and certainly nowhere near as threatening as the central bankers were making out that threat to be! And Greece has the worst numbers in that list.

“EZ countries are still fiscally sovereign, especially when it comes to decreasing spending and raising taxes.”

That is not fiscal sovereignty. It’s like calling competent in arithmetic someone who can only do addition and nothing else. Being able to run budget deficits OR surpluses through choice (instead of only surpluses) is necessary for true fiscal sovereignty.

Collecting taxes is the attribute of a politically sovereign government. When a country was militarily and politically conquered, in History, the conqueror used to impose on and collect taxes from his new subjects. That country was no longer politically sovereign.

“There is no problem with a pegged currency as long as you can maintain the peg. …

Argentina did quite well with the peg until Brazil devalued its currency in 1998 and the dollar revalued at the same time.

Unfortunately they didn’t break the peg at the time which was a huge mistake.”

I believe that what you’re saying is that pegging the currency is not a mistake but you have to un-peg it in time! Because otherwise still having it pegged when the other currency moves sharply is a mistake. I do not understand the logic. The whole concept of getting married to another currency, e.g. the Argentinian peso to the US dollar, is, like every religious marriage, “for good times & bad, sickness & health”.

Anders @ Saturday, April 2, 2011 at 8:52: Nicolai – Ireland leaving the euro and defaulting would not be a counter-example to MMT – quite the opposite!

I absolutely agree. The problem is that this is not how it would be perceived by the mainstream.

You have to be careful about the narrative that develops in the public opinion as a consequence of such events. I don’t think MMT advocates should hope for Euro nation defaults. Perhaps it would be more productive to point out the simple fact that these nations haven’t defaulted precisely because the currency sovereign (i.e. the ECB) is capable to sustain their debt indefinitely. Not that such an arrangement is a good idea politically, of course, but perhaps it’ll turn some heads.

Of course, in my experience, the biggest problem is getting people to understand that hyperinflation is not the consequence of monetary policies, but usually of extreme collapse in productive capacity combined with foreign denominated debts (this was the case both in Weimar and Zimbabwe).

Vassilis, the key word was relative, I don’t care at all about the absolute values.

This show how the PIGS became 20%-30% more expensive than Germany over that time.

(The case of baltic states was even worse: Lithuania 52%, Estonia 86%, Latvia 93%).

All these countries had the tools to fight inflation through fiscal policy, which is what MMT suggests.

A common currency is like a marriage, an agreement between two or more parties.

A peg is a unilateral policy. You should use it if it suits you. It suits the Chinese now to run

their export-led growth model, it suited Argentina to control hyperinflation.

MamMoTh, thanks for the response.

“The key word was relative, I don’t care at all about the absolute values.”

But the absolute values are showing something we’d be hard put to characterize as inflation; the respective CPIs were simply changing at a different rate. (Not by a big difference, anyway, but I will not stay on this point too much.) This does not mean they were “threatened by inflation”, as you claimed!

“The case of baltic states was even worse: Lithuania 52%, Estonia 86%, Latvia 93%. All these countries had the tools to fight inflation [before joining the Euro] through fiscal policy, which is what MMT suggests.”

The inflation in the Baltic states was most probably caused by factors unrelated to “too much money” being printed by crazed MMTers in the basements of the Baltic governments. 🙂 We should be looking at what happened to domestic manufacturing or imports. Off hand, I seem to recall a precipitous deterioration, at the time, of the Baltics’ relation with Russia, their main supplier of goods and services until then.

“You should use [the pegging of your currency to another one] if it suits you. It suits the Chinese now to run

their export-led growth model, it suited Argentina to control hyperinflation.”

Argentina “controlled” inflation to the colossal detriment of its citizens’ standard of living. The numbers were “put in order” alright; but the Argentines suffered. Argentina and its pegging the peso to the dollar was, IMO, a very clear example about how not to conduct fiscal policy.

The argument about China intentionally keeping its yuan devalued is rather old (and has already been addressed by Bill Mitchell in his blogs, e.g. “China is to blame”, December 8th, 2010). Classical economists whine about China that it is “cheating” (how??) , ignoring the fact that China’s conquest of foreign markets cannot have been the result of a trifle difference in costs, caused by “cheating” in the yuan’s parity, but can only be on account of the country’s huge advantage in the cost of products it exports. An advantage that exceeds “the difference that a stronger Yuan could achieve”, which means that even if the Yuan appreciated it would not help. “A revalued Yuan would just mean that Americans would pay more for Chinese imports, without reducing the amount imported by very much”.

Vassilis, I didn’t claim any inflation threat. This is my original claim about the EZ:

Countries which experience problems now are those who have had the highest inflation rates since the adoption of the Euro which resulted in a loss of competitiveness, which they could have avoided by raising taxes to decrease aggregate demand as MMT suggests.

Nothing to do with inflation or hyperinflation threats but with the effect of different levels of (even low) inflation over time, similar to the appreciation of sovereign currency.

The peg of the peso to the dollar actually improved the situation in Argentina until the dollar appreciated and Brazil devalued. This should have been the end of the peg. Even Cavallo, the mastermind of the peg admits it, Anyway, a peg is basically the only tool to fight hyperinflation, so I don’t think Argentina had much of a choice (the unofficial peg Brazilians implemented is probably better if it works).

The Chinese don’t care about how much does the US import but about how much they export. The appreciation of the yuan would mean less exports which is what they want to avoid. Contrary to the EZ countries they seem to be aware of the danger of relative inflation to that end and are using fiscal policy to tackle it. I guess they will try to keep the peg for as long as possible, that is when they reach a development level that permits them to export quality (like the Germans do) instead of cheap labour.

“Countries [in the Eurozone] which experience problems now are those who have had the highest inflation rates since the adoption of the Euro which resulted in a loss of competitiveness, which they could have avoided by raising taxes to decrease aggregate demand as MMT suggests.”

I disagree “on many fronts”: There was no serious inflation threat to begin with (EU’s main problem has been persistently high unemployment rates throughout the region); most EU-members’ trade is intra-Union trade, anyway; and where’s the causal link between “inflation” and “current problems”? Holland does not have problems (yet). And the average inflation rate in Holland was 2.08 percent between 1997-2010, practically equal to “problematic” Italy’s 2.15 average for the same period.

But the important point, for me, as I understand [sic] MMT, is that a Eurozone government can only decrease aggregate demand ! That’s like getting full sovereignty over my car but I can only use the brakes! Let me read that contract again.

“The peg of the peso to the dollar actually improved the situation in Argentina until the dollar appreciated and Brazil devalued.”

This sounds more like Roulette than responsible monetary policy, if I may say so. It’s probably even worse than Roulette; it’s like handing over your money to someone else to gamble it on Roulette for you.

“Even Cavallo, the mastermind of the [Argentinian] peg admits it.”

I would not take seriously the opinion of the man behind a plan if that plan ultimately fails! I’d seek other witnesses.

“The Chinese don’t care about how much does the US import but about how much they export.”

I’m sorry but America imports a significant part of Chinese exports. Why would the Chinese not care abt American imports?

But, still, in your response you are ignoring the fact that China is not like any other western, advanced nation where costs are close to America’s. China is a country whose huge population size and relative under-development allows for extreme “competitiveness” in costs. Even a thirty percent appreciation of the yuan would not make a serious dent to Chinese exports to Europe or the US! This is the point that people who complain about “Chinese cheating” should be focusing on.

Vassilis, I said it already several times. The problem is that of relative inflation between countries of the EZ.

This might have been a symptom of an unsustainable imbalance, and not the cause. Anyway, look at Ireland,

they were a below average country and became the country with the highest GDP per capita in the EU in no time.

Was there any fundamental reason for this? Not really, they attracted several IT companies, but mostly they

were building more and more houses at increasingly higher prices.

Inflation in Italy and the Netherlands was not above average in that period I think, that is why none of them is really

in trouble.

You seem to forget Cavallo had to fight hyperinflation. He chose a peg to the dollar to that end.

It might not have been the best choice, but he wasn’t in charge anymore in 1998 when it was clearly not

sustainable anymore. Seek other witnesses if you want. But the guy knows much more about inflation

than anything you can read in MMT blogs (maybe that’s why they only address the cases of Zimbawe and Weimar).

If the yuan were revalued the US and the ROW will import from another country with cheaper labour than China.

So China will export less, something they really want to avoid. That’s why they are concerned about inflation

although it’s only about 5%.

@MamMoTh

“Cavallo … knows much more about inflation than anything you can read in MMT blogs (maybe that’s why they only address the cases of Zimbawe and Weimar).”

Zimbabwe and Weimar are the most-often used arguments against MMT, on the issue of inflationary threats. If you have posted somewhere your refutation of the MMT analysis of these two cases of hyperinflation, I haven’t seen it.

“Inflation in Italy and the Netherlands was not above average in that period I think, that is why none of them is really

in trouble.”

Remember those words about Italy. (I trust you know what one of the ‘I’s in the acronym ‘PIIGS’ stands for.)

Vassilis Serafimakis, the MMT explanations for Zimbawe and Weimer inflations do seem to make sense but as MamMoth has asked it seems less obvious how the Brazilian hyperinflation can fit in with such a “supply collapse” MMT explanation. Is it possible that there are alternative routes to hyperinflation and MMT needs to be wary of a Brazilian style (irrational unwillingness to hold currency ?!?) hyperinflation even if supply collapse hyperinflation is not an issue? Perhaps for instance, a large flow of money through the tax system is a pre-requisit for insuring against a Brazilian style hyperinflation. I’m very ignorant about the Brazilian case and have never seen an MMT explanation of it.

Problem in the Baltics was clear: a housing bubble. Same as in the US, Ireland, Spain, maybe other places as well. Banks ability to create credit money can be either used responsibly, as in financing productive investment, or irresponsibly to bid up asset prices. Either way there is growth in aggregate demand, and the problem for eurozone is that different banking groups operate in different “modes”, meaning they either push easy money to the borrowers or behave conservatively. Often times these banks only operate in domestic markets creating divergence in asset markets and price levels.

Here is the classic cartoon that explains operation of the private credit money, money as debt II

http://vimeo.com/6822294

Stone

I know nothing of the Brazilian hyperinflation but I think I can address the notion of an “irrational unwillingness to hold a currency”. Of course this rejection of a currency is on the spectrum of possibilities, to say other wise would be a lie, but the question has to be looked at relative to the number of people currently holding the currency and how much they are holding. My read on the situation is that most bondholders want MORE money not less. They want HIGHER interest rates, which means they want more. When they stop asking for higher interest rates is when we should be worried it seems to me. As long as they are asking for more I see no problem. Considering the number of dollars circulating and the number of people with billions, I see very litle chance of a rejection.

Hi, I am little late, but would like to present the response of the ECB on our critics on this “educational” game http://www.ecb.int/ecb/educational/html/index.en.html

Anyway at lest they answered.

Regards

____

Dear Mr. Bastir,

Thank you very much for your feedback on €conomia.

€conomia is a game that explains, in a simplified way, how monetary policy works. It does not aim to explain fiscal policy, which is not within the mandate of the ECB, but a task of national governments in the Euro area.

Kind regards,

EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK

Directorate Communications

Educational Team

Kaiserstraße 29

D-60311 Frankfurt am Main

Tel: +49 69 13 44 7455

Fax: +49 69 13 44 7404

E-mail: education@ecb.europa.eu

—–Original Message—–

From: Gerhard Bastir [mailto:gerhard@bastir.at]

Sent: Thursday 07 April 2011 19:06

To: education

Subject: €conomia: Missing fiscal policy items to control inflation

To whom it may concern.

Hi,

I tried to “educate” me by using €conomia.

As the most concern in Europe is currently unemployment, I slashed

Interestrate immediately to 0% and got unemployment down from 7,11 at a

reasonable 1,84%. Then I decided to tackle rising inflation and found no

instrument for doing that. What kind of education may that game serve,

when the most important tools (fiscal instruments) to steer a economy by

regulating aggregate demand are missing?

Is this by error or for ideological reasons?

Pls advice when you have added at least a governmental spending- and

taxing- item into that “game”.

Otherwise it is worthless.

Regards

Gerhard Bastir