I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Something is seriously wrong

The Toronto G-20 leaders’ meeting is being held this weekend (June 26-27, 2010) and one expects it will endorse the position taken at the recent G-20 annual Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting in South Korea. The communiqué released from that meeting illustrates how influential the deficit terrorists have become. At the Pittsburgh meeting of the G-20 leaders in September 2009 the communiqué talked about the sufficiency and quality of jobs. Six months later they had abandoned that call and are now preaching higher unemployment and increased poverty via austerity packages imposed on fragile communities. This is in the context of dramatic increases in global poverty rates in 2009 due to income losses associated with entrenched unemployment. Then I note that the recently released 2010 World Wealth Report shows that the world’s rich got richer during the 2009 recession. The only reasonable conclusion is that something is seriously wrong in the world we have constructed.

The G-20 reversal is symptomatic of the direction the public debate is taking in the current period as the Flat Earth Theorists gain traction in the media and the lobbying circles. The sustained campaign against the fiscal support of the ailing world economy is making it harder for governments to do what we elect them to do – use their policy tools to advance public purpose.

The increasing constraints that governments are voluntarily accepting to satisfy the demands of amorphous groups such as the “bond markets” impinge on the democratic rights of every citizen. We expect our governments will act in the best interests of the nation. Sadly they are no longer doing that because they have fallen prey of the deficit terrorists. We introduced a new term for this phenomenon – democratic repression. Please read my blog – Amazing reversals – democratic repression – for more discussion on this reversal of policy position by the G-20.

The poor are getting poorer

The stock take for 2009 is as follows. World production (GDP) contracted by around 2 per cent overall in 2009 as private spending collapsed and government stimulus efforts were of an insufficient magnitude to provide the required spending offset.

The impacts of the recession was not evenly spread across the world. Western Europe saw real output decline by 4.1 per cent while Eastern Europe endured a collapse in real GDP of 3.7 per cent. In the Asia-Pacific countries (apart from Japan) real GDP grew by 4.5 per cent driven largely by the huge fiscal stimulus provided by the Chinese government.

At the same time, in its Global Economic Prospects 2010, the World Bank estimates that the global economic crisis pushed 50 million more people into extreme poverty in 2009 and a further 64 million will be added to this pool by the end of this year.

In this UNICEF paper – Inclusive Crises, Exclusive Recoveries, and Policies to Prevent a Double Whammy for the Poor – Ronald Mendoza argues that:

When it comes to aggregate economic shocks, the poor and the near-poor often face a double whammy. First, they are often among the most adversely affected by the shock, suffering from crisis effects that push them and their children (the next generation) deeper into poverty. Second, the poor and near-poor are also the least equipped to participate in and benefit from the subsequent recovery.

You can read a lay-person summary of the paper also.

While most of the research in this area of enquiry is focused on less developed (developing) nations, the research in advanced countries reveals similar outcomes. The poor are less exposed to crisis in the advanced nations and there are better safety nets.

But a person plunged into long-term unemployment in the US or Australia faces a high chance of becoming poor (relatively in this sense) and losing a significant proportion of the assets they had built up while working (housing etc). Their children also inherit the disadvantage that they grew up with and face major difficulties in later life.

So it is not just a developing country problem – although in the poorer nations the impacts mean death in many cases. In poorer nations, a crisis has devastating impacts. Mendoza notes that “tens of thousands of children in some of the poorest countries in the world could die, paying the ultimate price as a result of this crisis”.

The period of economic recovery is also fraught for the poor. I cover that issue in some detail in this blog – I am in denial – but I know children are dying.

In this context, the ILO recently released a report – Recovery and growth with decent work – published June 18, 2010, which urges the G-20 to place “employment and social protection at the centre of recovery policies”. The ILO note that:

… we must not forget that for many working women and men, and for many enterprises in the real economy, recovery has not yet started … Although job growth has reappeared, global unemployment is still at record levels. This is just the tip of the iceberg of discouraged jobseekers, involuntary temporary and part-time workers, informal employment, pay cuts and benefit reductions. There is still much suffering in many countries. Insecurity and uncertainty abound both for enterprises and for workers.

This is borne out by the persistently high unemployment that will remain for years to come not only impoverishing those directly involved but also setting up the conditions for intergenerational disadvantage as the children who grow up in jobless homes have been shown by the extant research to inherit the disadvantages of their parents. They suffer poor work histories and transit between one poorly paid job after another interspersed with lengthy periods of unemployment.

Arthur Okun coined the term “The Tip of the Iceberg” and I borrowed that for the title of a book I co-authored in 2001. The point is that the costs of recession and the resulting persistent unemployment extend well beyond the loss of jobs. Productivity is lower, participation rates are lower, the quality of work suffers and real wages typically fall.

Later the ILO Report says:

Many of the policy options facing governments and intergovernmental bodies will revolve around choices made necessary by inherent conflicts between human values and market values and between speculative and productive investments; choices which must respect the dignity of work and the way in which it underpins stable families and cohesive communities. They will also raise the question of equity: which sections of society should bear the brunt of the costs of the crisis, and how can the most vulnerable be better protected and empowered? Working families and small enterprises cannot be the real payers of last resort.

This is a very interesting statement and goes to the nub of the problem our nations and societies are now facing. There is a gross imbalance between “human values” and “market values”. While the neo-liberals continually try to convince us that there is a nexus between the two, the reality is that the pursuit of the latter always undermines the former.

The idea that self-regulating markets deliver some Shangri-La is one of the biggest con jobs to come out of the simplistic economic models that get rammed down students throats in university education. The text book models bear little if any relation to anything that is real.

You might also like to read these blog – What is it really all about? – which documents the way in which our priorities have been perverted by the neo-liberal agenda.

My ideological disposition tells me that the pursuit of human values is the only sustainable way of organising and running a world. The neo-liberal era has severely undermined that pursuit.

And now as we muddle through the worst recession in nearly 80 years the conservatives are once again re-asserting their dominance and the diversity of outcomes is there for all to see.

The recession has impoverished millions of people while the rich have found a way to make themselves even richer. I will come back to that last point later.

Unemployment and poverty as a loss of collective will

In the 1980s, we began to live in economies rather than societies or communities. It was also the period that unemployment persisted at high levels in most OECD countries. The two points are not unrelated. Unemployment arises because there is a lack of collective will. It does not arise because real wages are too high or aggregate demand too low. These are only proximate causes, if causes at all. The lack of collective will has been the principal casualty of the influence of economic rationalism.

Unemployment rates in almost all OECD economies have persisted at higher levels since the first OPEC shocks in the 1970s. The persistently high unemployment has been due to excessively restrictive fiscal and monetary policy stances by OECD governments driven by monetarist ideology. The rapid inflation of the mid-1970s left an indelible impression on policy makers who became captive of the resurgent new-labour economics and its macroeconomic counterpart, monetarism.

The goal of low inflation replaced other policy targets, including low unemployment. This has resulted in GDP growth in OECD countries generally being below that necessary to absorb the growth in the labour force and labour productivity. The battle against unemployment has been largely abandoned in order to keep inflation at low levels.

And now the economic crisis caused unemployment to sky-rocket from an already high base.

The loss of collective will has manifested over the last 35 years (or so) in a number of ways. Restrictive monetary policy pushed real interest rates to high levels for extended periods that resulted in lower than otherwise private capital expenditure.

Further, public capital expenditure cuts exacerbated the situation. As growth declined and unemployment rose, the resulting high cyclical budget deficits led to further cuts in public capital spending being justified by the balanced budget mania that accompanied the rationalist push.

The pursuit of balanced budgets also narrowed the range of policy instruments used. Accordingly, there has been an excessive reliance on monetary (interest rate) policy despite the bluntness of this instrument.

But the underlying cause is that the reemerging free market ideology has convinced us, wrongly, that government involvement in the economy imposes costs on us and we have thus supported governments who have significantly reduced their involvement in economic activity via spending and tax cuts and widespread deregulation and privatisation. The only way we will return to full employment, with everyone sharing in the benefits, is if the public sector increases its role in the economy.

In the The Death of Economics, Paul Ormerod (1994, pp.202-203) argues that the Post-WWII period of strong GDP growth, balance of payments stability, and high investment could have occurred without the low unemployment. He said:

The sole difference would have been that those in employment would have become even better off than they did, at the expense of the unemployed.

The higher tax rates and buoyant government sectors allowed the flux and uncertainty of aggregate demand to be shared. While the bulk of the OECD has abandoned this method of sharing, some economies have maintained high levels of employment into the current period. Ormerod (1994, pp.203) suggests that Japan, Austria, Norway, and Switzerland, among others have (in their own ways):

… exhibited a high degree of shared social values,, of what may be termed social cohesion, a characteristic of almost all societies in which unemployment has remained low for long periods of time … [and most significantly] … the countries which have continued to maintain low unemployment have maintained a sector of the economy which effectively functions as an employer of the last resort, which absorbs the shocks which occur from time to time, and more generally makes employment available to the less skilled, the less qualified.

The rich are getting richer

On Tuesday, the 2010 World Wealth Report was released by Merrill Lynch-Capgemini.

The Wealth Report considers the fortunes of high net worth individuals (HNWIs) who have “investable assets of US$1 million or more, excluding primary residence, collectibles, consumables, and consumer durables” and Ultra-HNWIs who have “investable assets of US$30 million or more, excluding primary residence, collectibles, consumables, and consumer durables”. So not your average person on the street.

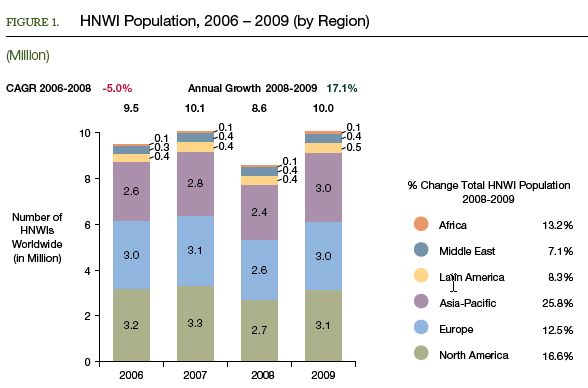

In relation to Figure 1 (below), the World Wealth Report says that:

The world’s population of high net worth individuals (HNWIs) grew 17.1% to 10.0 million in 2009, returning to levels last seen in 2007 despite the contraction in world gross domestic product (GDP). Global HNWI wealth similarly recovered, rising 18.9% to US$39.0 trillion, with HNWI wealth in Asia-Pacific and Latin America actually surpassing levels last seen at the end of 2007.

For the first time ever, the size of the HNWI population in Asia-Pacific was as large as that of Europe (at 3.0 million). This shift in the rankings occurred because HNWI gains in Europe, while sizeable, were far less than those in Asia-Pacific, where the region’s economies saw continued robust growth in both

economic and market drivers of wealth.The global HNWI population nevertheless remains highly concentrated. The U.S., Japan and Germany still accounted for 53.5% of the world’s HNWI population at the end of 2009, down only slightly from 54.0% in 2008. Australia became the tenth largest home to HNWIs, after overtaking Brazil, due to a considerable rebound.

After losing 24.0% in 2008, Ultra-HNWIs saw wealth rebound 21.5% in 2009. At the end of 2009, Ultra-HNWIs accounted for 35.5% of global HNWI wealth, up from 34.7%, while representing only 0.9% of the global HNWI population, the same as in 2008.

The following graph is taken from the Wealth Report 2010 (Figure 1).

How did this happen when world poverty and unemployment was going in the opposite direction?

The Report says:

Key drivers of wealth experienced strong gains. Many of the world’s stock markets recovered, and global market capitalization grew to US$47.9 trillion in 2009 from US$32.6 trillion in 2008, up nearly 47%. Commodities prices dropped early in the year, but rebounded sharply to end the year up nearly 19%. Hedge funds were also able to recoup many of their 2008 losses.

So the market values clearly swamped the human values.

Further reading of the Report reveals that the millionaires diversified their investments into “fixed-income investments seeking predictable returns and cash flow” which has presented a challenge to brokers to convince “clients to move off the sidelines and pursue riskier, more fruitful investments”.

So among the “safe” assets they diversified into were government bonds. If at this stage you feel like doing something nasty to your computer screen please resist the temptation.

This reinforces the theme I have been developing recently which demonstrates that the issuance of public debt is a major part of the corporate welfare system provided by the government. I most recently advanced this theme in this blog – Market participants need public debt.

In this light, all the cries that the unnecessary issuance of public debt will impose onerous burdens on the future generations etc are exposed as being ideological claptrap. The reality is that the public bonds provide significant benefits to the richest citizens in the world. They can use the public debt to hedge the insecurity that a major recession brings and actually benefit while the workers are losing their jobs and running down the meagre asset stocks they have managed to accumulate in better times.

I think this juxtaposition is one of the more obscene aspects of the way we organise our economic and financial system.

Conclusion

This polarisation of economic wealth and opportunity will be an enduring legacy of this crisis. The crisis has delivered the neo-liberals with an unprecedented opportunity to ram home their overall agenda which is to transfer as much real income (output) into the hands of the wealthy and to impoverish increasing numbers of workers to keep them docile.

The current policy agenda – austerity – will reinforce that dynamic.

There is very little being done to break the grip that the financial markets have on our economies. Governments are too gutless to stand up to them.

As a weekend reflection, I thought this quote from Paul Ormerod’s The Death of Economics was worth sharing. He is talking about the fabulous salaries earned by the largely unproductive financial markets and says (page 7):

James Tobin, the American Nobel Prize winner in economics, has questioned very seriously whether it makes sense from thepoint of view of American society as a whole to divert so much of its young talent from the top universities into financial markets. This debateis not new. John Maynard Keynes considered the same questionin the 1930s, and expressed the view that on the whole the rewards of those in the financial sector were justified. Many individuals attracted to these markets, Keynes argued, are of a domineering and even psychopathic nature. If their energies could not find an outlet in money making, they might turn instead to careers involving open and wanton cruelty. Far better to have them absorbed on Wall Street or in the City of London than in organised crime.

Admin note: changes to my blog

I am wanting to reclaim some more time (from work) to increase my family activities. I previously introduced the Saturday Quiz and then the Answers and Discussion blogs to minimise the weekend blog impost on my time.

But I now desire to reclaim even more time. So I am going to publish the Saturday Quiz on a Friday and the Answers and Discussion as usual on a Sunday and basically not write a dedicated blog on a Friday. That will give me a clear weekend for my other academic work and my family.

I will only deviate from this plan if something really interesting comes up on Friday that cannot wait until Monday. I cannot see that happening. This change will give me more time to drink cups of tea in cafes and hang out with those dearest to me. It will also give you – my dear readers – more time to read the archives.

This change will start from next week which is a convenient week to do this because I will be away in the US (Boston) all week (leaving Monday) to present a workshop on fiscal sustainability to a group of investment bankers. I will provide more detail about that on Monday. But next Friday I will be winging my way back across the Pacific Ocean to Sydney.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

Bill,

Can you please go into politics!

It’s clear that none of this is going to change and for a very long time as well.

Hello Professor Mitchell,

I have some questions about MMT.

Do you consider MMT to be a sub-branch or part of Post Keynesian economics?

Or do you think it is an independent theory in its own right? (even though it seems to have strongly Keynesian policy implications through fiscal policy, perhaps made more radical by Abba Lerner’s functional finance thesis).

What do you think of the work and macro theories of Paul Davidson, Geoff Harcourt etc and the other Post Keynesians? Do they also fail to properly understand MMT?

Regards

Also did you ever write your post on manufacturing?

Dear Andrew

You asked:

Not yet – but one day.

best wishes

bill

I think more effort is needed in explaining why ongoing fiscal stimulus won’t lead to the problems that beset countries in the 60s and 70s. Whenever I try to explain the virtues of ongoing govt spending to others, I often get the response that it was tried before and failed back then, and this view seems ingrained in the general public mindset.

I think one needs to look back far before the effects of the oil shocks of the early 70s. In the UK, unions were making and getting vastly inflationary pay demands well before 1973. I would like to see commentators on the left being honest about the problems of that time and why it won’t happen again this time if that road is followed. The neoliberal mindset would never have taken hold if things had been working well in the 60s and 70s. In the 70s we had the greedy unions. Now we have the greedy bankers. Same story, different actors. What is constant? Human nature.

What will make it different this time?

Dear Andrew

You asked:

I really don’t like to categorise things in that way. It also depends on what you mean by Post Keynesian economics. There is some analysis calling itself that which I can relate to and other analysis also calling itself PK which I reject outright.

MMT has a long tradition and for me goes back to Marx. For others, it goes back to Keynes. It clearly has been influenced by both as well as Kalecki, Lerner (functional finance), Minsky etc.

The people you mention are known to me and I would call friends (in the professional sense). I don’t care to comment on such a broad question other than to say I agree with many aspects of their work but I also have serious disagreements with them on matters pertaining to budgets and money. I would consider them to be deficit doves, in the main.

best wishes

bill

Bill, for the past 2 months (when I found out about you) I’ve done nothing but just reading your blog (try to read all the archives) and reading many papers from Levy Institute, and UKMC.

I’m from Malaysia an currently doing Phd Economics in the UK, you are very much true when you said that none of the conventional economic models could provide clear answer or even satisfying description of what caused and why this crisis is happening. Thank God that I found your blog and now I feel very much relieve, contrary to what been taught to us that this crisis could not be solved by a ‘pro people comprehensive policy’ since everything are subjected to the ‘market dynamic’, you could provide the only workable alternative that I’ve been seeking for.

I would love to bring your idea (MMT) to be included as a subject at economic faculty in Malaysia, since I been lied for most of my Undergraduate and Graduate life I feel very much compel to teach the truth for our future generation.

By the way, my younger brother is going to ANU early July for Bsc in Economics, I advise him to play along with the system for a while and at the same time to constantly read your blog. . .

To be honest, I could make sense of economics and its dynamic more by reading your blog than using other models

“Keynes argued, are of a domineering and even psychopathic nature … Far better to have them absorbed on Wall Street or in the City of London than in organised crime.”

Keynes was right and wrong at the same time. The psychopaths landed in finance and also built a very successful organized crime ring.

I think MMT counter-terrorism with respect to the bond market is misguided or at least fuzzily focused.

The bond market exists as an instrument of active monetary policy. If the central bank takes an active approach to adjusting the short term rate, the market will take an active approach to incorporating expected monetary policy into interest rates, where it can. Moreover, to the degree that the central bank adopts active policy rate management, this will affect interest rate risk directly in terms of the short rate. That interest rate risk spills over into the cost of paying interest on the deficit. If the deficit mechanism is no bonds and reserves only, and interest on reserves is paid only the short rate, that interest rate risk poses a concentration of interest rate risk that is unacceptable by any prudent standard. On the other hand, if policy is actively managed, and interest on reserves is paid throughout a term structure of reserve deposits, the risk profile and the pricing of it is equivalent to having bonds. So the real reason for issuing bonds when the central bank actively manages the policy rate is to diversify interest rate risk. Bonds are only an issue for MMT because the central bank actively manages the policy rate.

The counter-terrorism campaign shouldn’t be focused so much on bonds. Bonds are only the symptom. The problem (from an MMT perspective) is active management of a short term policy rate for monetary policy purposes. MMT’s true terrorism threat in that sense is not from bonds, but from central interest rate management. The only counter-terrorism response that makes true sense in this regard is the zero natural interest rate, with no bonds as the sweetener.

There will be no attempt to balance the budget…MMT has won, but no one in Washington will admit it yet. The lack of a budget resolution says it all, I think.

The psychopaths landed in finance and also built a very successful organized crime ring

Professor William K. Black (University of Missouri at Kansas City) has been especially articulate about this.

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/search/label/William%20K.%20Black

Black on the reform bill that just passed:

Source

The counter-terrorism campaign shouldn’t be focused so much on bonds. Bonds are only the symptom. The problem (from an MMT perspective) is active management of a short term policy rate for monetary policy purposes. MMT’s true terrorism threat in that sense is not from bonds, but from central interest rate management. The only counter-terrorism response that makes true sense in this regard is the zero natural interest rate, with no bonds as the sweetener.

I would agree with this politically. The point is to change policy and reduce suffering globally in the process of globalization that will occupy this century. This will require both education and political action. People need to understand how the financial system operates relative to the economy, and the economy relative to society, in terms of both theoretical possibilities and practical options. Then we can start talking about the option based on reality, instead of on myth, confusion, obfuscation, and fallacious argumentation based on erroneous assumptions.

I do think that the no bonds proposal is a useful tool, however. I suspect that it is in this spirit that some MMT’ers have proposed it. It introduces the shock factor. Once people realize that bonds are unnecessary, the whole universe of discourse shifts, since it is now presumed that “the bond market” has the last word on policy. I think that it is important to establish that no bonds is a viable option and that there are good reasons for considering it. But I don’t think it is something to lobby for with great effort first.

The immediate challenge is reversing the present political course that is captive to neoliberal ideology. The latest Gallup poll in the US puts 42% of respondents identifying as conservative or very conservative, and only 20% liberal. This is a huge problem heading into the elections of ’10 and ’12.

Speaking of profits and looting.

How does MMT treat the paradox of profits ?

[In a closed system without external exchange, with money created by banks through loans, the private sector financed by such loans can hope to recover only the original loans by selling the totality of their products. When the principal was repaid, there is nothing left for either profits or even interest (see the circuitist theory, e.g. Graziani)].

Steve Keene approached the problem with some unorthodox accounting, but some mmt’er (I do not recall who exactly) commented that (s)he was puzzled by the paradox without elaborating much.

Since the private sector consolidated sheet balances to zero, how do mmt’ers ‘monetize’ profits in the accounting sense ? Where does money come from (my hunch is that the CB has to be involved to generate new money)? Could an mmt’er in the know describe a more or less detailed sequence of money flow through balance sheets that leads monetizing profits ?

I am familiar with various circuitist attempts to solve the paradox, however, I could not find any SFC MMT treatment of the problem.

Thanks.

This is another word for the value realization problem – how to account for redistribution of real surplus via value representations (e.g., money forms).

Clearly, there must be an “injection” of representation forms in order to account for surplus (as well as a destruction of forms in some cases, but let’s be optimistic). It isn’t quite that simple, as real surplus tends to lose unit value and demand patterns shift. Also, timing and relationships are important – government spending (for example) might put more savings into households, whereas government bailouts apparently put more money into executive paychecks.

So you get our Rube Goldberg, jerry-rigged, contingent existing system that neo-classical economists think can be modeled with fairly simple math. Go figure.

Keen is far from neo-classical – he is applying what looks (to me) like very sophisticated models to understand system stability and cycles, with a focus on private debt effects. He still has a neo-classical view of value, however – seeing it as a consequence of machine productivity + technology. His early post graduate work included attempts to disprove Marx’s labor theory of value – Keen highlights Steedman’s critique of the “Transformation Problem” in his introduction history of econ lectures. Unfortunately, that critique has been shown to be false (just iterate the transformation of input/outputs 5 times and you get the same answer as the simultaneous equations). Having said all that, I like Keen and his work – he just needs to figure out how to include government spending in his model and not get freaked out over government debt levels.

Without an discussion of what value is, the realization problem can’t be addressed – I don’t believe this is an area that MMT addresses anyway – but I think it helps one understand the political structures built into the monetary system.

There’s no need to get into dynamic models or a philosophical discourse about value in order to explain profits.

As long as people can create and sell IOUs, you have the possibility of profits, in the form of being a net accumulator of the IOUs.

Here profit needs to be taken in some context — you are not earning stockpiling bags of currency in your basement. All income is spent. Some on IOUs and the rest on non-IOUs (i.e. goods, labor, capital investments, etc.).

So even though all cash-flows net to zero, that does not mean that no one can accumulate financial assets.

In a growing economy, everyone can accumulate a growing stock of IOUs in a non-ponzi fashion. And the “sustainable” rate of IOU growth is growth rate of production, assuming stable prices.

But even if the economy does not grow, you can still time shift, by spending less on non-IOU’s when you are young and then selling the IOUs for goods when you retire.

This is in addition to the possibility of ballooning profits due to excess IOU issuance, or the deflation of profits due to too insufficient IOUs being issued.

And once you introduce governments, the government can supply profits by deficit spending, funding that spending by any combination of new IOUs or new currency, depending on its taste for one over the other.

But you don’t need government deficit spending to explain profits. You don’t even need banks. All you need is a market for IOUs.

ooh, just to interupt everyone,

Obama has called for co-ordinated action, whilst showing concern about early cuts in deficits.

DECODE:

It’s okay to defict spend, as we (the US) are going to do the same, in order to get growth. Therefore, by co-ordinating our spending, the relative values of our currencies should stay the same – it’s clear as day!!! Yipeee!!!

Michael Hudson, Europe’s Fiscal Dystopia: The “New Austerity” Road to Serfdom

Hudson’s analysis applies to the US as well. He covers a lot of ground and lays out the plan the bankers have in store to recoup and are now implementing through the G20 and the central banks. It’s pretty devastating.

On the issue of deficit terrorists, do people notice how often the idea that government debt is a Ponzi scheme gets tossed about?

I have tried to refute it here, with some use of MMT:

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2010/06/rolling-over-government-debt-and-debt.html

I have probably made a mistake by referring to “debt monetizing”, but maybe people here are interested in reading it.

Ormerod (1994, pp.203) suggests that Japan, Austria, Norway, and Switzerland, among others have (in their own ways):

… exhibited a high degree of shared social values,, of what may be termed social cohesion, a characteristic of almost all societies in which unemployment has remained low for long periods of time …

This is very interesting – shared social values, social cohesion. I know in japan’s case I read about latin based japanese that were allowed to work in the country for a time, but some were being pressured to leave japan and return to latin america so they don’t hurt the “real” japanese people and employment. It seems USA is the “melting pot” of social values and cohesions and probably does not have the cohesions as tight as the nations listed above.

Tom Hickey: “I do think that the no bonds proposal is a useful tool, however. I suspect that it is in this spirit that some MMT’ers have proposed it. It introduces the shock factor. Once people realize that bonds are unnecessary, the whole universe of discourse shifts, since it is now presumed that “the bond market” has the last word on policy. I think that it is important to establish that no bonds is a viable option and that there are good reasons for considering it. But I don’t think it is something to lobby for with great effort first.”

Well, I think that it would be interesting to try it in a public debate with a debt/deficit hawk. “The debt is too big, it is out of control, it is a burden to our children and grandchildren. We should pay it off.”

“OK. Let’s do that. Let’s just print the money. {sic}”

Deficit hawk has apoplectic fit. 😉

(Yeah, yeah. Technically it’s not printing money. But printing money is a metaphor ordinary people can quickly understand. A lot of them think that’s how we get our money, anyway. 😉 )

Anon,

Interest rate risk of central bank itself ?

Andrew: “On the issue of deficit terrorists, do people notice how often the idea that government debt is a Ponzi scheme gets tossed about?”

Yes, indeed, I have. Here is how I have thought of dealing with it, but I am not sure.

A. Bank debt is like a Ponzi scheme. Banks create money by making loans. However, they require the loans to be paid back plus interest. In a world with only bank money, the borrower either has to roll over the debt or default, or somebody else has to borrow money and spend it. Without defaults and bankruptcies the system has to grow like a Ponzi scheme. And like a Ponzi scheme, there will eventually come a day of reckoning, when there are not enough new borrowers, and the system collapses in a financial crisis.

B. On the surface, gov’t debt looks the same. However, with gov’t debt there is no day of reckoning, because even if nobody is able and willing to lend to the gov’t, the gov’t can simply create money. (If such a day came, there would surely be other problems in the economy, but the gov’t need not default or go bankrupt.)

Recently I have heard that A is not accurate, because the banks are also able to create the interest in time for it to be paid back without rollover or other borrowing. Is that so? If so, how does it work?

Central banks in many countries except the ones whose liabilities are in demand (“foreign reserves”) try to keep the interest rates sufficiently high to put a deflationary bias on the aggregate demand. This is done so that the current account is in surplus and they don’t want the scars from the past to happen again. They also have to manipulate rates to attract foreign demand for their currencies and want to keep their currencies acceptable in global markets. What keeps them awake at night? The fear of a currency fall. Of course, weaker currency is good in some sense but the worry is about a plunge in exchange rates. When their currencies get weak faster, the level of imports doesn’t adjust so fast – people still have to go to work and use oil. Fall in currency also indicates that there could be a further fall and it is scary. High volatility is bad for the acceptability of their IOUs which a country wants if she wants to have strong international trade.

Min,

That story about banks (“A.” in your example) is Steve Keen’s story. Unfortunately his story about banks doesn’t work because of his own rules of accounting which are not self-consistent.

Banks have build positive net worth and also build capital over time. They can make profit consistent with the rules of accounting. The fact that they take huge bets and end up closing down is a different matter. It has to do with how the regulators are doing their jobs and how incentives are structured etc.

Ramanan,

Interest rate risk for the central bank is a secondary institutional issue.

I’m thinking primarily of interest rate risk on the interest cost of government debt, where the central bank retains active management of the policy rate as the core mechanism of monetary policy.

(PLEEEEESE don’t come back and say it’s irrelevant because governments aren’t financially constrained.)

🙂

pebird@at 11:18:

Thanks, but I was hoping that someone could describe an SFC matrix or give a verbal explanation showing how new money/tokens are created, in the accounting sense, to monetize profits.

RSJ@12:31 :

I am not interested in the philosophical part of the new value creation, just in proper accounting.

Imagine the following:

A capitalist/”firm” takes a loan of 1000 tokens. Then, the firm spends the loan on production factors, for simplicity only on wages. The workers make products and consume all the output paying 1000 tokens. The “firm”pays back 1000 tokens worth of principal, but cannot pay interest or realize monetary profits — there is no tokens to do that.

If, hypothetically, the “firm” tries to charge more than 1000 (to realize a profit), there is no one to pay as there is no additional money on hands in the form of wages.

How does the new money gets into the system ? What is the MMT solution of the conundrum (or logical denialt that such a conundrum exists).

Thanks.

Ok Anon I won’t and wouldn’t have 🙂

So you are saying that its some kind of strategy where they try to minimize the interest payments ? So you are distinguishing “natural rate is zero” and “no bonds” and analyzing the latter for the moment ?

Going back to the issues of financial constraints and sustainability, I think its closely tied up with international trade and acceptability of currency in international markets. Of course, one way to beat it is through concerted action by simultaneous fiscal expansion but then it starts resembling the Euro Zone issues – some countries will complain that they will not “take” the debt/gdp ratio to x% etc. Just telling you about the new ideas in my head (picked up from places) and why I wouldn’t have come back saying it is irrelevant.

Ramanan,

Under “zero natural rate”, there is no interest rate risk.

That’s because the short rate is permanently zero.

It doesn’t matter whether this is done with bonds or reserves because the market isn’t going to pay a risk premium for term structure when there is no interest rate risk (or at least a lot less of a risk premium than when the central bank actively manages the policy rate into non-zero territory.)

Given the objectives of a “zero natural rate policy”, there’s no rationale for the government providing a term structure, either through bonds or reserves. The intention is that the rate always be zero. The only consistent implementation of a zero natural rate policy is to eliminate bonds and just dump reserves into the banks as a result of spending, while paying no interest on those reserves.

i mean no interest rate risk with respect to government liabilities

there is interest rate risk with respect to credit spreads over the zero risk free rate (you can call this credit risk as well, but it manifests as an interest rate change)

the one exception on government liabilities is that if the government did offer a term structure that was tradeable (bonds or reserves), there might be a premium for the “regime risk” of the possibility that the government could back off its zero rate policy at some future point – which to me is why the zero natural rate as a policy choice actually resembles a fixed rate regime, ironically (and to the horror of MMT advocates)

sorry, I’m really not addressing your open economy issues, am i

anon, which to me is why the zero natural rate as a policy choice actually resembles a fixed rate regime

I don’t see it that way. It seems to me that in natural rate = zero the CB is allowing a constant by an operational choice, although the CB retains the ability to choose differently. Under a fixed rate system, the rate is determined independently of the CB, e.g., convertibility agreed to by treaty or a currency board peg , and the CB is constrained by it. No constraint involved when the CB lets excess reserves accumulate and the overnight rate falls to zero.

Anon,

Yes the open economy is slightly tangential to it – but its just my obsession that I try to bring that in everything 🙂

Yes there is no bonds in the zero rate proposal – just reserves changing out of deficit spending and changes because of transactions of foreign central banks.

You are saying that in the present world, bond issuance is not the main culprit – just the central bank interest rate targeting is the culprit. Once the central bank targets an interest rate and whether it pays interest on reserves or not, bonds automatically have to be issued at all maturities because just paying the interest on reserves is not prudent, as you put it. And no bonds is only for the special case.

Kumar:

Remember that banks (or firms through a market) can issue IOUs (as RSJ notes) – you can look into the Real Bills doctrine as to whether bills of exchange used for issuing currency is a destabilizing factor as a historical reference.

However, while I disagree with RSJ on the importance of value, I won’t take up a discussion here. As said above, Keen (also Minsky) basically say that using a “market” for IOUs (which is as good a definition for banks as any) will necessarily create crises. Although Keen’s accounting is incomplete – his model still illustrates fundamental systemic instabilities.

Min – look at Minsky per debt as a Ponzi scheme.

In my view, the crises come from a political fight within the financial sector over dividing up claims. This is reflected in the “real” economy as an over-production crisis – but I happen to think that factor is overstated historically, but that is just my opinion – the over-production (for example, housing) is a symptom, not the cause.

Per your question about profit realization – while the profit paradox (banks create money/IOUs with offset assets, but don’t create “free” money for profits) – it is true that expanding IOU’s can stand-in as profits for a while – but none of these IOUs forms are universal/public – all are private/contractual and require a market for trading (despite others best efforts to abstract them to close to money (“liquidity”) forms – e.g., derivatives, etc.).

Remember to include “motion” or time in your model – in other words, while the firm is issued 1000 token and goes about its business, there has to be other entities functioning in different phases of whatever cycle you propose. This is how private IOUs can stand-in for profits for a period of time – I argue that these profits are “unrealized” in aggregate, although particular entities may be able to realize their individual profits. I don’t think you can use MMT to answer your question as it is currently structured.

By definition, privately-issued IOU cannot be universal/public. At some point during the private IOU expansion, a sufficient number of entities will try to realize their claims at roughly the same time. We can speculate whether they do this in a coordinated fashion and/or whether the dynamics of the system (e.g., maturities lining up at the same time) will force them to do so. They believe the value of their claims will be diluted in the future, so they act to liquidate (transform their IOUs toward the universal). Others quickly follow, hence crisis. Gold was the universal in the past, now it is CB-issued liabilities.

You can call this a capital accumulation crisis, a debt crisis, an over-production crisis, all related. This process has occurred repeatedly during history – with the exception of the “quiet period” after WWII, financial crises were fairly common – every 7 to 10 years, with larger ones every 15 to 25 years.

In my humble view, the post-WWII managed economy included a process for controlled profit realization via government fiscal policy with monetary (treasury/CB) and coordinated market mechanisms. It was not perfect by any means, but it represents a brief (30 year) historical experiment that demonstrated some of the components of an improved form of economic/monetary functioning. This was not in the interests of some, and they worked hard over those 30 years to chip away and dismantle this imperfect but very functional system. We live in interesting times.

VJ Kumar,

There is some debate in the literature and I think solving it by words don’t help too much. One has to draw something called transactions flow matrices to address this. Here is an article by Gennaro Zezza on how to do it. Some Simple, Consistent Models of the Monetary Circuit

There is another way of doing it, if you are ready to go through a lot of inventory and inflation accounting, and I refer you to the text of Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie called Monetary Economics, in particular chapter 9. The authors say that Graziani has had an influence on their work and it is in the same circuitist attitude.

I am not sure why some authors keep bringing it up – would like to know.

VJ Kumar,

There is some debate in the literature and I think solving it by words don’t help too much. One has to draw something called transactions flow matrices to address this. Here is an article by Gennaro Zezza on how to do it. Some Simple, Consistent Models of the Monetary Circuit

There is another way of doing it, if you are ready to go through a lot of inventory and inflation accounting, and I refer you to the text of Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie called Monetary Economics, in particular chapter 9. The authors say that Graziani has had an influence on their work and it is in the same circuitist attitude.

I am not sure why some authors keep bringing it up – would like to know.

RSJ,

While we can keep arguing about “you don’t even need banks”, please show us some links to models which do not involve banks and the fact that other IOUs are traded and neoclassical results are not obtained.

While that is a request for a reference, I certainly don’t wish to get involved in a debate about banks 🙂

Ramanan at 1:29 :

I am familiar with Zezza’a article. There are two issues with his article:

1. He treats only interest (profits are assumed to be zero if the loan is to be repaid)

2. The initial loan must include wages *plus* interest payments if the loan is to be repaid, a rather odd constraint.

Are you aware of a more realistic profit monetizing SFC work ? So far, it seems that the SFC/circuitist work I saw leads to a conclusion(theoretical but maybe not practical) that profits are an aberration and economics is a zero sum game.

Thanks.

VJ,

One view to take is that since governments run a deficit, profits are possible.

The second ref I provided has households, firms and banks and firms producing and selling of inventories and accumulating them. Firms and banks are able to pay profits. It is true that firms are indebted to banks forever, but whats the problem ?

The point about the paradox is that people seem to ignore something or the other when even when writing down the equations. The stock-flow models are the right way of approaching it.

The paradox of profit seems to be like one Zeno paradox which says that the arrow cannot move.

VJ,

Quoting G&L page 261

So in the economy you are considering, firms can borrow from banks to distribute their profits.

Indeed, examples can be easily built where profitable firms, with looming profits, face negative cash flows because of their fast-rising inventories

This is a serious problem for may small firms that are very “successful.” They cannot manage the necessary cash flow because they don’t have sufficient credit lines established yet to expand with demand for their product. Typically, they seek to be acquired by larger firms that can provide the necessary capital for expansion. But some are even killed by their own “success.”

It is true that firms are indebted to banks forever, but whats the problem ?

As I understand Michael Hudson, the “magic of compound interest” ultimately catches up with ability to service debt. That’s why in ancient times there were periodic debt jubilees, like every seven years, in order to reset. It’s also what bankruptcy laws are supposed to take care of, so that the system does not bog down in debt and become susceptible to massive debt deflation.

Of course, this is an oversimplification of Hudson’s work. MInsky showed that a lot more is involved in the periodicy of financial cycles.

Tom Hickey,

“I don’t see it that way. It seems to me that in natural rate = zero the CB is allowing a constant by an operational choice, although the CB retains the ability to choose differently. Under a fixed rate system, the rate is determined independently of the CB, e.g., convertibility agreed to by treaty or a currency board peg , and the CB is constrained by it. No constraint involved when the CB lets excess reserves accumulate and the overnight rate falls to zero.”

Wow, you really want to have your cake and eat it too. The zero natural rate is institutionalized by definition. The central bank becomes a zombie department of the government. There is a commitment by the government to abandon interest rates and active central banking as a tool of monetary policy. The central bank’s independence and its meaningful existence are subsumed by fiscal policy. What you are describing is not a ZNR regime, but a central bank that happens to have rates temporarily at zero. Japan is such a case now.

Countries abandon a gold peg when it becomes overly constraining and they want to reflate.

Greece may abandon its Euro “peg” because it wants to reflate through money and the exchange rate rather than deflate wages and spending.

A ZNR regime may abandon its zero rate institutional structure if it decides it wants more flexibility than taxes and spending to tighten monetary policy. If government bonds or term reserves are outstanding and subject to market pricing, term interest rates will start to incorporate the possibility of moving off the zero “fixed” rate regime.

In fixed exchange rates, it is possible for the central bankers to set the interest rates. In other words, there is nothing endogenous about interest rates in fixed exchange rate regimes. This is true even if there is capital mobility and the reason it is true is because of imperfect asset substitutability. If a central bank suspects huge chasing of wealth and a lot of speculative activity and lesser imperfect asset substitutability, it can change the rate. Its a matter of choice and there is nothing automatic about it and is useful to call it exogenous at every point. The movement of the central bank is more appropriately described by its central bank reaction function. The central bank has no choice but to set the rates. Their only option is to vary the short-term rate of interest at which they supply liquidity to the banking system on demand.

Ramanan at 3:07 :

One view to take is that since governments run a deficit, profits are possible.

It may be an interesting point of view if one could show stock-flow consistent flow of new money from the CB into the capitalist pockets with the presumption that this is the *only* way of monetizing profits, not just one of many possible ways. The implications of such model could be quite unpleasant I am afraid.

It is true that firms are indebted to banks forever, but whats the problem ?

Well, if I understand you correctly, the problem is that such a model is unsustainable as the debt grows to infinity, potentially.

Ramanan says at 3:28 :

So in the economy you are considering, firms can borrow from banks to distribute their profits.

The problem with the above is a potentially infinite debt growth.

VJ .. in those models bank loans are matched by the levels of inventories. No blow up of debt occurs.

Thanks to Ramanan and pebird for your helpful replies. 🙂

Ramanan at 6:48 :

Sorry, I do not follow. Are you saying that the loan is repaid to the bank in kind ? So that extra goods are converted to monetary profits by the bank ?

Could you offer a numeric example ?

Anon, Wow, you really want to have your cake and eat it too. The zero natural rate is institutionalized by definition. The central bank becomes a zombie department of the government. There is a commitment by the government to abandon interest rates and active central banking as a tool of monetary policy. The central bank’s independence and its meaningful existence are subsumed by fiscal policy. What you are describing is not a ZNR regime, but a central bank that happens to have rates temporarily at zero. Japan is such a case now.

True, of course. I was referring to the CB allowing excess reserves to accumulate without paying a support rate, allowing the rate to fall to zero. MMT’ers, (“Natural” means IAW law of least action.) Some MMT’ers have advanced this approach.

Others are more radical. Some people, including me, would like to the “independent” CB’s abolished as anti-capitalistic and anti-democratic. That is not an MMT proposal, however, but a libertarian one (with a small “L”). Hayek and Friedman were for getting rid of the central bank function altogether, and a lot of people on the right are now clamoring for it, because it is essentially a command system rather than a market approach. I would like the CB to recognized as a government function, hence, fully accountable to the voters.

The historical fact is that when the CB is “independent,” it is run by the elite and is unaccountable to the voters as part of government. The result is that the people controlling rates and regulation consider money’s chief purpose to be as a store of value, hence, the monetary policy is run for the wealthy. That this not public purpose, and it is just wrong-headed in a supposedly democratic society with representative government.

{Refer to MIchael Hudson’s post to which I provided a link in my 6.26 @ 13:25, where he speaks to CB “independence” and its nefarious consequences.)

V. J. Kumar: The problem with the above is a potentially infinite debt growth.

Ramanan: VJ .. in those models bank loans are matched by the levels of inventories. No blow up of debt occurs.

And as Minsky observes, those models are based on simplistic assumption. In reality, the debt does eventually “blow up,” due to financial instability. As long as IOU’s remain good, the chain remains unbroken. But when they don’t, then the chain breaks.

R,

I can’t give you a ref! The standard models assume bonds. No equity or banks. I’m not saying that this is a good thing. Then you have models that have banks lending to firms — again not a description of reality. And of course neither of these models makes a distinction between long and short term rates. I haven’t seen a macro model that has anything other than a 1 period bond, for example. There are partial equilibrium financial models that look at this, but no macro –i.e. economy-wide — models.

A good model would have households borrowing from banks and firms borrowing from the credit markets, together with forward-looking optimization. The model would also contain the institutional constraints placed on banks that determine how much they can arbitrage their own funding costs to control other people’s funding costs. You would have different effects from a household debt bubble versus a firm investment bubble.

But counting models isn’t an argument.

The point is that, in order to have profits, all you need are the IOUs. Once you can buy and sell both goods and financial assets, then you have a flexible money supply and the possibility of sustained profits even in a non-ponzi manner. The IOUs are what allow this to happen, not bank debt per se, although a serious model needs to include bank debt as well as credit market debt.

@Tom,

Thats not exactly how I understand it. God (via the Mosaic Law) had the Isrealites assign the lands via allotment for them to use for 7 years. At the end of the 7 years, it was re-alloted (crop rotation?) within the tribes, they reassigned the use of the land via a new allotment (they cast lots again). Larger families and those with more agricultural wherewithall would get more lots to cast. One could not convey the land during the allotment as it was not theirs to sell (it was Gods). One could sort of rent it out for the remander of the 7 year period (it was not considered a “debt” as you could not charge interest ie the natural rate of interest is zero) for some sort of participation (this type of event was probably due to death in the family/change in capabilities/illness?) , but this was revokeable at any time for the balance of the 7 years by the one who received the original allotment, and otherwise went back for reassignment at the end of the original 7 year period so the “tennant” couldnt be locked in to serfdom due to signing a sub-prime mortgage for 30 years. God prevented the Rentier. This was God’s way of establishing a Job Guaranty as it provided every family a proportionate way to earn a living for themselves by Law and the specific arrangements were refreshed every 7 years.

Resp,

Tom Hickey: “The historical fact is that when the CB is “independent,” it is run by the elite and is unaccountable to the voters as part of government. The result is that the people controlling rates and regulation consider money’s chief purpose to be as a store of value, hence, the monetary policy is run for the wealthy.”

Indeed. But right now it is the function of money as a medium of exchange that is most important.

Matt, see Michael Hudson, The Lost Tradition of Biblical Debt Cancellation

Also his Thinking the Unthinkable: A Debt Write Down, and Jubilee Year Clean Slate

But right now it is the function of money as a medium of exchange that is most important.

Exactly. The problem is lagging aggregate demand (not enough medium of exchange circulating) rather than inflation/inflationary expectations (corruption of store of value).

But the CB’s are neoliberal institutions and their mission to promote “investment” and protect the value of money as a store of value. As a result they are promoting austerity, either right away (Europe) or as soon as possible (US).

But as Michael Hudson observes in the link about it’s more devious than that. The objective to transfer wealth from the middle class to the financial sector, i.e., the wealthy, in order to make them whole. This is being done by the president under the idea that 1) what is good for the financial sector is good for the country (NOT), and 2) that future “obligations” are unsustainable (NOT). It is another rip off, pure and simple.

As Winterspeak observes here and here the financial sector is pro-cyclical and depends on demand, not the reverse.

Tom Hickey says: Saturday, June 26, 2010 at 13:25 Hudson’s analysis ….. It’s pretty devastating.

Dear Tom H,

Michael of course, sees everything through a focused historical ‘lens darkly’, reflecting probably quite accurately on political and economic history, forces past and present in societies – but not on the broad sweep of being human.

Are there enough good people in the world with enough understanding to resist such forces?

I think so – why? Same history: no-one yet has broken the human spirit, enslaved the human soul, captured the human imagination or fettered the creativity and power of discrimination of the human mind; stopped a sentient human being from feeling what they do, or expressing it in song – only broken irreplaceable, uniquely human bodies on a rack. In every land, freedom is a human passion; the human heart ever seeks peace.

It’s just greed we are dealing with here. An ‘imperfection’ as I understand it.

Cheers …

jrbarch

VJ,

As I said, the paradox of profits is like one of Zeno’s paradoxes which says that the arrow cannot move. The opposition to any solution such as debt blowing up is like offering another of Zeno’s paradox which says that sum of a infinite series is infinite and one cannot cross the ground (because for that one has to cross half of it, half of the remaining, half of the remaining etc.).

In the steady state, it is possible for the total loans to be finite and equal to the level of inventories and the producers paying an interest on it and still making a profit and banks getting interest income out of the loans from firms etc. You have to look at the math, difficult to say it in words without going through another round of questions on the explanations.

These are the two Zeno paradoxes I am talking of

That which is in locomotion must arrive at the half-way stage before it arrives at the goal.

It’s similar to

In a race, the quickest runner can never overtake the slowest, since the pursuer must first reach the point whence the pursued started, so that the slower must always hold a lead.

The Zeno paradox analogy is my own but the fact is I don’t see any problem with the paradox of profit. However, it offers some insights and the role of credit money.

Missed the first one is If everything when it occupies an equal space is at rest, and if that which is in locomotion is always occupying such a space at any moment, the flying arrow is therefore motionless. (ref: Wikipedia)

Thank god for differential calculus, or we could never get from point A to point B.

Zumar: If you want to create a completely closed model, where everything reconciles at the end of whatever cycle your model has, without any monetary injection, you of course end up in a paradox.

But if you are going to have IOUs (whether from banks or some other entity), you need to put time in your model at which point at the end of any given cycle, there will be outstanding IOU balances which represent your monetary expansion. The aggregate financial value of these IOUs can never be “extinguished”, they represent anticipated future growth, and a continuous expansion is required for stability. At least, that is my assertion.

To simplify things, set the discount/interest of your IOUs at 0%, so that profits/capital are solely a function of firm activity. Once that is working, you can split profits between real and financial by modeling an interest rate on IOUs.

Also, you may want to consider modeling contraction as well as growth – and this is the Achilles heel of the system.

The problem is that the system is designed to deal with 80% of reality. It moves great in one direction (growth), but when there is a contraction, it’s like running sewage through the fresh water pipes.

Whether this is stable or not depends on your time horizon and how you view human nature.

Ramanan:

Thank you for your input.

I do not see though the Zeno paradoxes’ relevancy where the underlier is the notion of infinity which is not the case with finite number of accounting transactions forming (allegedly) monetary profit. Besides, if one is willing to adopt the point-set continuum framework, a.k.a secondary school calculus, the paradoxes cease to exist in such a framework(of course one may be unwilling to adopt such a model as not being ‘true’ to reality, or for other reasons, but at least there is a consistent model !).

One would hope that, with MMT ascribing so much importance to correct accounting of money flows between various entities, there may be a non-hand-wavy but rather numeric explanation of monetizing profits.

Disclaimer: the above comment is not intended to diminish the importance of the MMT world-view despite its obvious limitations that may exist only in my imagination 🙂

pebird at 1:25 :

If you want to create a completely closed model, where everything reconciles at the end of whatever cycle your model has, without any monetary injection, you of course end up in a paradox.

But the private sector, taken as whole in the accounting/stock flow/balance MMT sense, is just such “a completely closed model”. Would you suggest that monetizing profits happens *only* when the government inject money into the private sector ?

Thanks.

VJ,

My point on bringing in the Zeno’s paradoxes was just to illustrate the nature of the paradox of profit. I am totally unsure about why it is an issue. Some questions cannot be put in words and you won’t find the solution using just words. As I said, in the G&L reference I provided, they indeed have things not ending up in any paradox. Its a dynamical model and is as close to the theory of monetary circuit as possible. All stocks and flows are taken care of.

I haven’t seen the MMT’ers discussing the profit paradox.

V J Kumar: “A capitalist/”firm” takes a loan of 1000 tokens. Then, the firm spends the loan on production factors, for simplicity only on wages. The workers make products and consume all the output paying 1000 tokens. The “firm”pays back 1000 tokens worth of principal, but cannot pay interest or realize monetary profits – there is no tokens to do that.

“If, hypothetically, the “firm” tries to charge more than 1000 (to realize a profit), there is no one to pay as there is no additional money on hands in the form of wages.”

OC, money could be added to the economy by the gov’t. 🙂

But I think that there is another way. Suppose that there is another firm that borrows money, but goes bankrupt. The bank writes down the loss, but meanwhile there is money in circulation that can go to the profits of the first firm. 🙂

Capitalists talk about the freedom to fail. But actually, isn’t failure necessary to the overall system?

pebird:

I’ve shortened my name for convenience, but it caused my prev. message to be re-moderated and possibly lost. Here’s what I wrote earlier(apologies for likely double-posting):

pebird at 1:25 :

If you want to create a completely closed model, where everything reconciles at the end of whatever cycle your model has, without any monetary injection, you of course end up in a paradox.

But the private sector, taken as whole in the accounting/stock flow/balance MMT sense, is just such “a completely closed model”. Would you suggest that monetizing profits happens *only* when the government inject money into the private sector ?

Thanks.

Min at 2:04 :

money could be added to the economy by the gov’t.

That’s what I thought MMT’ers might have in the back of their minds. The notion has some uncomfortable implications, ‘the government lining up the pockets of greedy capitalists with profits’ being one of them.

Suppose that there is another firm that borrows money, but goes bankrupt. The bank writes down the loss, but meanwhile there is money in circulation that can go to the profits of the first firm

I believe Zazzaro (?sp) tried that approach — profits at the expense of failed companies — that leads to the idea of zero-sum in the absence of growth since the bank has to lose part of its capital due to the bad loan write off.

Thanks.

Yes, the private sector is a closed model – and without government (or the private sector functioning as one through a smooth issuance of expanding private IOU’s), you will hit your paradox.

I don’t suggest that monetizing profits happens (e.g., occurs as an event) only when the government injects funds. But some “injection” is required. Any number of private financial forms can also monetize profits, and theoretically could continue to do so IF there was some kind of regulator between the real economy and the financial sectors.

Now of course there is a regulator – it’s called the market and crises – and many of us assert this is a stupid way to regulate and besides, it is completely game-able if you have enough power/resources at your disposal. You would have to believe that without conscious/public regulation, interests between private entities will always align. Well, they do in long run, say the classical economists. And Keynes noted that “in the long run we are all dead”, in other words – freedom and equality in the long run is meaningless.

So, if the private sector could act “fairly” – and the idea that pricing mechanisms, competition and supply/demand can do this are ridiculous (IMHO) – then basically the private sector would provide what the government does. I believe this is kind of the libertarian view – but it implies a very weird notion of human nature.

If you believe in a stocks and flow model, you have to recognize that there are lags in certain functions and the system will self-adapt over time to take these lags into account (of course, creating new lags). Realization of profits is one of those lagging functions (and a critical one). My view is that government spending acts to “lubricate” the smooth functioning of the system via growth and profit realization. Profits can be realized through any number of financial forms – as long as participants are confident they can be transformed into whatever universal form is in place (currently CB liabilities – money).

If that is true, it kind of corresponds to what the Fed has been doing over the last couple years. Now, they are only guaranteeing certain kinds of financial forms, unfortunately I cannot securitize my expected lifetime income (unless we want to argue that this is what a mortgage truly is) and get bailed out during a crisis, but government spending that creates some demand helps a little bit.

I think you need to take a more macro view – trying to model a mechanism where a particular government spending quantum gets traced through the system and finally ends up in some financier’s wallet is like trying to understand hydraulics by tracing individual H20 molecules. Let me tell you, I tried this with thinking through the timing of government debt issuance and government spending a few weeks ago and ended up with some 500+ comment (on another blog site) thread that proved I was on the absolute wrong track.

VJ Kumar: “I believe Zazzaro (?sp) tried that approach – profits at the expense of failed companies – that leads to the idea of zero-sum in the absence of growth since the bank has to lose part of its capital due to the bad loan write off.”

According to economists, markets are not in general zero-sum. But that is in terms of utility, not money.

In any finite time period, the private sector is zero sum in terms of money, if loss write-offs are included in the accounting. Right?

pebird:

Thank you for your comments !

I think you need to take a more macro view – trying to model a mechanism where a particular government spending quantum gets traced through the system and finally ends up in some financier’s wallet is like trying to understand hydraulics by tracing individual H20 molecules. Let me tell you,

It would be an interesting trace if possible at all– macro without micro seems to be on too shaky a foundation here, though.

I tried this with thinking through the timing of government debt issuance and government spending a few weeks ago and ended up with some 500+ comment (on another blog site) thread that proved I was on the absolute wrong track

Could you please provide a reference ? I’d be curious to see the comments.

@Tom,

Thanks for those Hudson links! (i intend to read the one on Babylon several times over I have never seen work like that)

I did not know that such debt forgiveness was practiced as widely in the Ancient world…seems the potentates would periodically do it to gain political favor with the masses of subjects when it got out of control and edict some form of restrictions but then it would come right back again (ancient version of the repeal of Glass-Steagall)….The God of Israel seemed to want to prevent it in the first place…that apparently didnt work out too well for them either at least so far! 🙂

But I dont know if I agree with it for now. Alot of these banksters probably are in hock the most: boats, 20m house in hamptons, condos, planes, etc…maybe a ‘bottom up’ jubilee, absolve ourselves of the first $250k of household debt and first $100k of student loans…maybe…

Resp,

Matt, I think that the top end of town wants a jubilee for itself, but not for the rest of us.

You are right. A lot of wealthy people are either in hock on underwater assets or holding paper that is worthless.

The “austerity” movement emanating from the top is the mechanism for the jubilee for themselves. Government forbearance allows them to not to have to disclose insolvency, and preferential treatment permits them to extract their losses from workers, sticking “lesser people” with the bill for their own excesses. A devilish plan, to be sure, but that’s what it boils down to. It’s pure predation.

I recommend Hudson’s Financial Capitalism versus Industrial Capitalism (Doc file)

These discussions would benefit from a distinction of what banks do versus what non-financial firms do. And another distinction between credit markets and banks. There is a war between bank profits and non-financial profits, as they fight over the same pool of profits; and there is a war between investment banks and other investors — e.g. pension funds — as they trade against each other, with the banks busily robbing everyone else, due to their institutional backing and lower funding costs. Hudson’s piece highlights the consequences of both.

Tom,

When reading Hudson, it is really hard to avoid recalling Carroll Quigley’s “Tragedy and Hope.” In particular: “The powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent meetings and conferences. The apex of the systems was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the world’s central banks which were themselves private corporations. Each central bank…sought to dominate its government by its ability to control Treasury loans, to manipulate foreign exchanges, to influence the level of economic activity in the country, and to influence cooperative politicians by subsequent economic rewards in the business world.”

RSJ, exactly. At the top, this is a conflict over splitting the pie between rent-seeking and productive investment, with finance gaining an increasing cut over recent years. Simultaneously, financial and industrial capitalists are allied against workers because they believe that lower compensation is to the advantage of both of them, and they are seeking to harness the power of the state through capture to advance their shared purpose.

Roger, Professor Quigley (who was teaching history at Georgetown University when I was a student) had it right. Since he wrote these words, the direction has been clear. It is epitomized by the BIS, the IMF World Bank, etc., and especially the EMU, in which the ECB is a central bank without a corresponding political counterpart, there being no European sovereign central government. The push will be on for currencies managed by central banks like the EMU, to whom sovereign governments cede monetary sovereignty. The end in view is a single global currency managed by a world bank without a corresponding democratic world government. That consolidates the control of wealth without political accountability, which is the overall objective.

This is the real motive behind central bank independence in the first place – which is why I am opposed to this institutionally as anti-democratic. While the New World Order conspiracy theorists are confused about the facts and issues, the basic insight that independent central banking is anti-democratic and threatens liberty is correct. As Michael Hudson observes, the road to serfdom now lies through debt peonage to financial capitalism rather than the totalitarian communism that Hayek opposed. Financial capitalism now depends on central bank “independence” and state capture to operate freely.

The wealthy have always distrusted democracy, which is a reason that most democracies are representational rather than direct. These are in effect oligarchies controlled by the powerful and influential through state capture. The result is de facto oligarchy, specifically plutocracy. These people think that this is a natural state since they are the ones who have come out on top, or share in the genes that came out on top. Hence, they rule by “evolutionary” right, which is just another form of the ancient idea of aristocracy based on birth. We see this is the BP chairman’s calling his victims “the small people” and Alan Simpson’s echo of it in ‘the lesser people.”

Tom Hickey: “The wealthy have always distrusted democracy, which is a reason that most democracies are representational rather than direct.”